SULAWESI

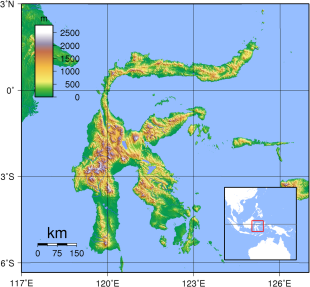

Sulawesi is a huge funny-shaped sland east of Borneo and Kalimantan, south of the Philippines, west of the Moluccas and north of Flores. According to the BBC Sulawesi sprawls like a drunken starfish in the western Pacific Ocean, its four emerald limbs reaching into the Celebes, Molucca and Flores seas. Formerly known as Celebes, it is about the size of Nebraska and consists of four large peninsulas fringed by coral reefs and covered by large wildernesses areas with marshy coastal plains and jungle covered mountains in the interior. There are also smoking volcanoes and large agricultural areas. Off the coast in some places are distinctive Sulawesi fishing platforms.

Provinces of Sulawesi: Area in square kilometers, Population in 2010, Population in 2014, Density per square kilometers:

South Sulawesi: 46,717.48, 8,034,776, 8,395,747, 179.7

West Sulawesi: 16,787.18, 1,158,651, 1,284,620, 76.5

Central Sulawesi: 61,841.29, 2,635,009, 2,839,290, 45.9

Southeast Sulawesi: 38,067.70, 2,232,586, 2,417,962, 63.5

Gorontalo, 11,257.07, 1,040,164, 1,134,498, 92.9

North Sulawesi: 13,851.64, 2,270,596, 2,382,941, 172.0

Total Sulawesi: 188,522.36, 17,371,782, 18,455,058, 97.4

Sulawesi is home to about 21 million people (2025). It accounts for about 10 percent of Indonesia's area and 7 percent of its population. It has lost 90 percent of its rich lowland forests to logging and agriculture. Many of the highland forests are still in good condition. Most people tend to live on or near the coast. The interior is generally sparsely inhabited. The major ethnic groups in the south are the Bugis and the Makassarese. The Toraja occupy the southern highlands. A mosaic of other groups are scattered across the island.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS ON SOUTHERN SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF SOUTHERN SULAWESI: LIFE, SOCIETY, BOATS factsanddetails.com

SOUTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTH EAST SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR HISTORY, GOWA, TRADE, RELIGION AND SIRI (HONOR) factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR CITY AND REGION factsanddetails.com

BUGIS: LANGUAGE, HISTORY, RELIGION. ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com

BUGIS LIFE AND CULTURE: SOCIETY, FAMILY, FIVE-GENDERS factsanddetails.com

BUGIS SAILING TRADITIONS: SHIPS, PIRACY, WHALE SHARKS factsanddetails.com

TORAJA: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

TORAJA RELIGION: AFTERLIFE, PRACITIONERS, CHRISTIANITY, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

TORAJA FUNERALS: RITUALS, BELIEFS, COSTS, EVENTS factsanddetails.com

TORAJA BURIALS: TOMBS, TAU TAUS AND THE WALKING DEAD factsanddetails.com

TORAJA SOCIETY AND LIFE: FAMILIES, FOOD, HOUSES, WORK factsanddetails.com

TORAJA CULTURE: ART, TEXTILES, MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN AND CENTRAL SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MINAHASANS: HISTORY, LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL SULAWESI: BADA VALLEY MEGALITHS, LAKE POSO, LORE LINDU NATIONAL PARK factsanddetails.com

NORTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

DIVING IN NORTH SULAWEST BUNAKEN ISLAND AND THE LEMBEH STRAIT factsanddetails.com

GORONTALO factsanddetails.com

Wallace Line

Indonesia’s, Asia's and Oceania's flora and fauna is divided by the “Wallace Line”, an invisible biological barrier described by and named after the 19th-century British naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace. Running along the water between the Indonesia islands of Bali and Lombok and between Borneo and Sulawesi, it separates the species found in Australia, New Guinea and the eastern islands of Indonesia from those found in western Indonesia, the Philippines and the Southeast Asia.

The Wallace Line marks a point of transition between the flora and fauna of Western and Eastern Indonesia and acts as the western boundary of West Nusa Tenggara, which includes the islands of Lombok and Sumbawa. After all these centuries, the wildlife remains nearly unchanged.In Indonesia the Wallace Line runs between Bali and Lombok, continuing north between Kalimantan and Sulawesi. West of the Line, vegetation and wildlife are Asian in nature, whereas east of the Line, these resemble those of Australia. The animals of Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Java west of the Wallace Line are similar to those found on Peninsular Malaysia.In Sulawesi, the Maluku Islands, and Timor, east of the Wallace Line, Australian types begin to occur. Bandicoot, a marsupial, is found in Timor. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007; Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy, Republic of Indonesia]

For more information on the Wallace Line See BIODIVERSITY IN SOUTHERN ASIA: WALLACE LINE, HOTSPOTS, RARE SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Geography and Geology of Sulawesi

Sulawesi is the world's 11th-largest island. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, it is situated in Indonesia west of the Maluku Islands, north of Flores and Timor, and south of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago of the Philippines. Within Indonesia, only Sumatra, Borneo, and Papua are larger in territory, and only Java and Sumatra are more populous.

Sulawesi covers an area of 186,216 square kilometers (71,898 square miles) (including minor islands administered as part of Sulawesi). The interior of Sulawesi is dominated by rugged mountain ranges, which have historically isolated the island’s peninsulas from one another. As a result, communication and travel between regions were traditionally easier by sea than by land.

Three large bays divide the island from north to south: the Gulf of Tomini, the Tolo Gulf, and the Gulf of Boni. These gulfs separate the Minahasa (Northern) Peninsula, the East Peninsula, the Southeast Peninsula, and the South Peninsula. The Strait of Makassar runs along the island’s western coast, separating Sulawesi from Borneo. The island’s highest peak is Mount Latimojong, which rises to 3,478 meters (11,411 feet).

Sulawesi rises from deep surrounding seas to a rugged, largely non-volcanic mountainous interior, with active volcanoes concentrated on the northern Minahasa Peninsula and extending toward the Sangihe Islands. The island formed through complex tectonic collisions involving fragments from the Asian, Australian, and Pacific plates, leaving it heavily faulted and prone to earthquakes. Off its eastern coast, tectonic processes created the North Banda Sea and thick carbonate platforms during the Miocene. Unlike most islands in Wallacea, Sulawesi is a composite landmass shaped by plate collisions and later fragmentation, rather than a purely oceanic island.

Earliest People in Sulawesi

Archaic humans arrived on Sulawesi — an island in Indonesia just east of Borneo — at least 118,000 years ago, 60,000 years older than previously thought, based on the 2015 discovery of deposit of stone tools and extinct animal bones. Archaeology magazine reported: It is known that various hominin species made it to the islands of Flores, Java, and Papua by this time, and it was assumed that Sulawesi was part of their dispersal. This new find, accumulated over what appears to have been tens of thousands of years, suggests there was, in fact, a well-established population. There are no human fossils, so it is unknown what ancient human species it was. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

Rock art and hand prints found in caves in Sulawesi have been dated to nearly 40,000 years ago. Deborah Netburn wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Archaeologists working in Indonesia say prehistoric hand stencils and intricately rendered images of primitive animals were created nearly 40,000 years ago. These images, discovered in limestone caves on the island of Sulawesi, are about the same age as the earliest known art found in the caves of northern Spain and southern France. The findings were published in the journal Nature. "We now have 40,000-year-old rock art in Spain and Sulawesi," said Adam Brumm, a research fellow at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and one of the lead authors of the study. "We anticipate future rock art dating will join these two widely separated dots with similarly aged, if not earlier, art." [Source: Deborah Netburn, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2014 ~\~]

See Separate Article: EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

Toalean people were ancient, enigmatic hunter-gatherers who lived on Indonesia's Sulawesi island, known for unique tools like 'Maros points' and microliths, existing before Austronesian farmers arrived around 3,500 years ago. They hunted warty pigs, gathered shellfish, and left behind enigmatic artifacts, with recent DNA from a burial (Leang Panninge) revealing connections to early modern humans in Wallacea and traces of Denisovan DNA, suggesting complex migration patterns in the region.

In 2021, researchers announced that they had have uncovered the 7,200-year-old remains of a teenage girl in Sulawesi presumably from the Toalean culture. DNA extracted from the “Leang Panninge” remains—named for the cave where she was found—shows that the 17–18-year-old belonged to the prehistoric Toalean culture, an elusive hunter-gatherer group that mysteriously vanished about 1,500 years ago. The findings, published in Nature, offer new insight into ancient human migrations across the Wallacea region, a chain of Indonesian islands used as “stepping stones” by early modern humans traveling between Eurasia and Oceania more than 50,000 years ago. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, August 26, 2021]

See Toleans Under OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

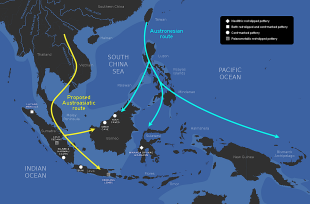

Early History of Austronesian-Speaking Malays in Sulawesi

Austronesian-speaking Malay agriculturalists entered Sulawesi from the Philippines approximately 4,000 years ago. Compared with regions farther west, Indian cultural influence was relatively limited, although pre-Islamic burial sites containing Chinese, Siamese, and Annamese porcelain indicate that Sulawesi played an important role as a trading stop on routes to the spice-producing Moluccas. The earliest kingdoms, first mentioned in fourteenth-century Javanese sources, emerged in eastern Luwu and were initially based on control of iron resources. Over the following three centuries, village confederations developed into monarchies whose rulers claimed divine ancestry through possession of arajang, sacred regalia believed to have descended from heaven.

A bronze Amaravati-style statue was discovered in 1921 at Sikendeng, near the Karama River in South Sulawesi, and was dated by Bosch (1933) to between the 2nd and 7th centuries AD. Later, in 1975, small locally produced Buddhist statues from the 10th–11th centuries were found at Bontoharu on Selayar Island, also in South Sulawesi.

From the 13th century onward, access to prestige trade goods and sources of iron began to transform long-established cultural patterns, enabling ambitious leaders to form larger and more complex political units. Why these developments occurred simultaneously remains unclear, though one may have driven the other. By 1367, several Sulawesi polities were recorded in the Javanese Majapahit-era manuscript Nagarakretagama. Canto 14 mentions Gowa, Makassar, Luwu, and Banggai, suggesting that by the 14th century these polities were integrated into a wider maritime trading network centered on the Majapahit port in East Java. Around 1400, emerging agricultural principalities appeared in the western Cenrana Valley, along the south coast, and on the west coast near present-day Parepare.

Trade, Colonialism and the Dutch in Sulawesi

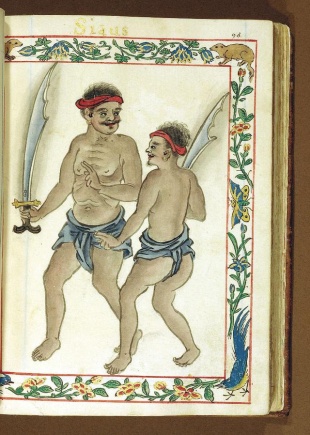

The ancient Chinese made it to Sulawesi. Some people today make their living today by digging up the graves of Chinese mariners and unearthing porcelain from the 11th century Song and Ming dynasties worth thousands of dollars. The mariners were often interned together and grave robbers have found 11th century vases using steel rods to probe the soft mud where they were buried. Two of the most famous products from Celebes were Makassar poison, which, according to 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys, was given by Englishmen to dogs in their gentlemen's clubs to watch them die, and Makassar oil, which men used to grease back their hair. It was once described as the greasiest of the "greasy kids stuff." [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

The first Europeans to reach Sulawesi were Portuguese sailors, including Simão de Abreu in 1523 and Gomes de Sequeira in 1525, who arrived from the Moluccas in search of gold. A Portuguese base was established in Makassar in the early 16th century and remained until 1665, when it was taken by the Dutch. The Dutch had arrived in 1605, followed soon after by the English, who set up a trading factory in Makassar.

From 1660, the Dutch waged war against Gowa, the dominant Makassar power on the west coast. In 1669, Admiral Speelman compelled Sultan Hasanuddin to sign the Treaty of Bongaya, granting the Dutch East India Company control over trade. The Dutch were assisted by the Bugis warlord Arung Palakka of Bone, who emerged as regional overlord while Bone became the dominant kingdom. The Dutch constructed a fort at Ujung Pandang, and political and cultural development subsequently slowed under this new balance of power.

Later History Sulawesi

In 1905, Sulawesi was fully incorporated into the Dutch colonial state of the Netherlands East Indies, a status that lasted until the Japanese occupation during the Second World War. During the Indonesian National Revolution, Dutch forces under Captain Raymond “Turk” Westerling carried out the South Sulawesi Campaign, in which hundreds, possibly thousands, were killed. After the transfer of sovereignty in December 1949, Sulawesi became part of the federal United States of Indonesia, which was dissolved in 1950 when the island was absorbed into the unitary Republic of Indonesia.

Indonesian independence brought name changes: Celebes became Sulawesi and the capital Makassar became Ujung Pandang. Later it was changed back to Makassar. There was a Sulawesi independence movement that has since died out. In the chaos after independence, Islamic fundamentalist groups on Celebes held a foreign medical team hostage for 18 months. There were only two survivors. People in Sulawesi have demanded the return of land taken away by a Suharto family company.

Poso district in central Sulawesi endured a wave of violence between December 1998 and 2002 that left between 1,000 to 2,500 dead and thousands more injured. Scores of churches and mosques were burned and 100,000 people were forced to flee their homes. At one point, so many had left Poso city—the capital of Poso district—it was described as a 'dead city'. [Source: Lorraine V Aragon, Inside Indonesia, April-June 2002. Aragon teaches anthropology at East Carolina University ]

See Separate Article: MUSLIM-CHRISTIAN VIOLENCE IN INDONESIA IN POSO, SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

Languages of Sulawesi

Sulawesi is one of the most linguistically diverse islands in Indonesia. A total of 114 indigenous languages are spoken on the island, all of which belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. With an estimated population of about 20.8 million people in 2024, Sulawesi exhibits far greater linguistic diversity than Java, Indonesia’s most populous island, where only four to eight languages are spoken by more than 150 million inhabitants. [Source: Wikipedia]

Nearly all of Sulawesi’s languages fall into five major subgroups that are spoken almost exclusively on the island. These are the Gorontalo–Mongondow, Sangiric, Minahasan, Celebic, and South Sulawesi language groups. Only three languages spoken in Sulawesi fall outside these categories. Indonesian Bajau belongs to the Sama–Bajaw subgroup and is used by traditionally nomadic coastal communities known as the Bajo, who are scattered across eastern Indonesia. Makassar Malay and Manado Malay, by contrast, are Malay-based creole languages.

In terms of deeper classification, the Gorontalo–Mongondow languages are part of the Greater Central Philippine language group and are therefore more closely related to the languages of the central and southern Philippines than to most other Sulawesi languages. The Sangiric and Minahasan languages are also linked to the broader Philippine subgroup. Meanwhile, the Celebic and South Sulawesi languages represent primary branches of the Malayo-Polynesian family.

Language vitality on Sulawesi varies considerably. Major languages such as Buginese, spoken by around five million people, and Makassarese, with roughly two million speakers, remain widely used and robust. Many smaller languages are also still actively spoken within their communities. However, some languages are severely endangered, having lost speakers to dominant regional languages; Ponosakan, for example, reportedly has only a handful of remaining speakers.

Religion on Sulawesi

About 82 percent of Sulawesi’s population is Muslim (2023). The process of Islamization began in the lowlands of the southwestern peninsula in the early 17th century. The kingdom of Luwu, on the Gulf of Bone, was the first to adopt Islam in February 1605, followed later that year by the Makassar kingdom of Gowa–Talloq, centered on present-day Makassar. In contrast, the Gorontalo and Mongondow peoples of the northern peninsula largely converted to Islam only in the 19th century. Most Muslims in Sulawesi adhere to Sunni Islam. [Source: Wikipedia]

Christianity forms a significant minority, accounting for about 17 percent of the population as Protestants and less than 2 percent as Roman Catholics. Christian communities are concentrated in the northern peninsula, particularly around Manado, where the Minahasa people—predominantly Protestant—are the main inhabitants. Christianity is also prevalent in the Sangir and Talaud Islands at the northern tip of Sulawesi. In the south, many Toraja of Tana Toraja converted to Christianity after Indonesian independence, while other Christian populations are found around Lake Poso in Central Sulawesi among Pamona-speaking groups and in the Mamasa area.

Despite formal adherence to Islam or Christianity, many Sulawesi people continue to observe local beliefs, rituals, and reverence for indigenous deities alongside world religions. These syncretic practices remain an important part of cultural life across the island. Smaller religious communities are also present. Hinduism and Buddhism are practiced mainly by Balinese, Chinese, and Indian minorities, while very small numbers of adherents follow folk religions or Confucianism.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026