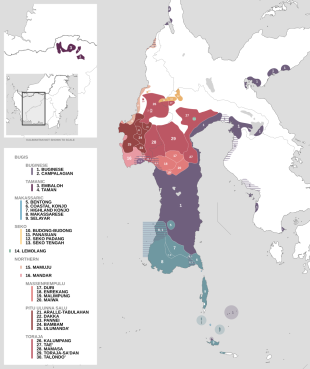

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHWESTERN SULAWESI

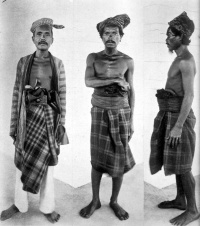

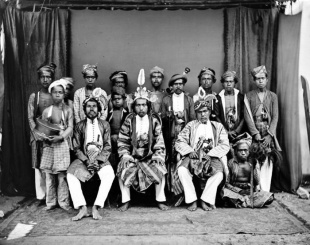

Bugis are the predominate ethnic group on the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi. Also known as the Boegineezen, Buginese, To Bugi, To Ugi' and To Wugi' they are one of the most well-known, sea-faring people in Southeast Asia. They have traveled widely and colonized numerous coastal areas and have a long association with piracy. "The Bugis are among the strongest ethnic groups in the archipelago, politically, economically and culturally," Sudirman Nasir, a Bugis who works in public health in South Sulawesi, told the BBC. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Makassar People live in southwestern Sulawesi. Also known as the Makassarese, Makassaren and Mangkasaren, they once ruled a powerful maritime kingdom and have traditionally been rivals and cultural cousins of the Bugis, occupying an area of southern peninsula of Sulawesi south of the area occupied by the Bugis. Their name for themselves is “Tu Mangkasara,” meaning “people who behave frankly.” As is true with the Bugis the have been staunchly Islamic and independent minded and the rhythm of their agricultural and maritime life is influenced by the monsoon seasons.

Toala live in the mountains of southwest Sulawesi. Also known as the East Toraja, Luwu, Teleu Limpoe, To Ale, they are former hunter-gatherers who are now primarily subsistence farmers and workers at copra plantations. Some are Muslims but many have retained their traditional animist beliefs. There were about 30,000 of them in 1983. In the old days they were divided into three subtribes ruled by hereditary chiefs but now have an elected chief. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF SOUTHERN SULAWESI: LIFE, SOCIETY, BOATS factsanddetails.com

SOUTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTH EAST SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR HISTORY, GOWA, TRADE, RELIGION AND SIRI (HONOR) factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR CITY AND REGION factsanddetails.com

BUGIS: LANGUAGE, HISTORY, RELIGION. ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com

BUGIS LIFE AND CULTURE: SOCIETY, FAMILY, FIVE-GENDERS factsanddetails.com

BUGIS SAILING TRADITIONS: SHIPS, PIRACY, WHALE SHARKS factsanddetails.com

TORAJA: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

Mandarese

The Mandarese ((pronounced MAHN-duh-reez) are an Austronesian ethnic group that live in West Sulawesi and have been known for centuries for their seafaring abilities. They are dominant group in province of West Sulawesi area. Using their traditional sandeq boats, Mandarese cruise to all over Indonesia and reached as far as present-day Malaysia and Australia. People who live in mountainous areas have a culture similar to that of the Torajans, especially in terms of house architecture, language, clothes and traditional ceremonies.[Source: Wikipedia; Joshua Project]

The Mandar language belongs to the Northern subgroup of the South Sulawesi languages group of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. The closest language to Mandar is the Toraja-Sa'dan language. According to the Christian group Joshua Project their population in the early 2020s was 565,000 and 99.9 percent of them were Muslims Before regional administrative divisions were established, the Mandarese, together with the

Bugis, Makassarese, and Toraja peoples, formed the cultural mosaic of South Sulawesi. Although West Sulawesi and South Sulawesi are now separated by political boundaries, the Mandarese remain historically and culturally closely connected to their cognate communities in South Sulawesi. The term “Mandar” refers to the collective identity formed by seven coastal kingdoms known as Pitu Ba’ba’na Binanga and seven river or upstream kingdoms known as Pitu Ulunna Salu.

Ethnically, the Pitu Ulunna Salu—commonly referred to as Kondo Sapata—are classified as part of the Toraja group and are concentrated in Mamasa Regency and parts of Mamuju Regency. In contrast, the Pitu Ba’ba’na Binanga comprise a range of dialects and languages. Together, the strength and interdependence of these fourteen kingdoms gave rise to the concept of Sipamandar, meaning brotherhood and unity among the Mandarese people. This unity was formalized through an ancestral covenant sworn at Allewuang Batu in Luyo.

Mandarese History

Historically, the Mandarese consisted of seventeen kingdoms: seven upstream kingdoms known as Pitu Ulunna Salu, seven estuary kingdoms called Pitu Ba’ba’na Binanga, and three additional kingdoms collectively referred to as Kakarunna Tiparittiqna Uhai. The Mandarese adopted Islam beginning in the early seventeenth century. [Source: Wikipedia]

The seven kingdoms of the Pitu Ulunna Salu alliance were: 1) Rante Bulahang; 2) Aralle; 3) Tabulahang; 4) Mambi; 5) Matangnga; 6) Tabang; 7) Bambang. The seven kingdoms of the Pitu Ba’ba’na Binanga alliance were: 1) Balanipa; 2) Sendana; 3) Banggae; 4) Pamboang; 5) Tapalang; 6) Mamuju; 7) Benuang. The three kingdoms of Kakarunna Tiparittiqna Uhai in the Lembang Mapi region were: 1) Alu; 2) Tuqbi; 3) Taramanuq.

The upstream kingdoms were well adapted to mountainous environments, while the estuary kingdoms possessed extensive knowledge of maritime conditions. The Mandar region bordered Pinrang Regency in South Sulawesi to the south, Tana Toraja Regency to the east, Palu in Central Sulawesi to the north, and the Makassar Strait to the west.

Throughout Mandar history, numerous figures emerged to resist Dutch colonial rule, including Imaga Daeng Rioso, Puatta I Sa’adawang, Maradia Banggae, Ammana Iwewang, Andi Depu, and Mara’dia Batulaya. Despite this resistance, Mandarese territories were eventually occupied by the Dutch East Indies. The enduring resistance ethos, known as the “spirit of Assimandarang,” persisted until the Mandar region was officially recognized as the province of West Sulawesi in 2004.

Mandarese Society and Culture

Mandarese society retains strong elements of traditional social relations. Feudal nobility, including descendants of former rulers known as mara’dia (princes), continues to play a role within modern administrative and governmental systems. An important social shift has also been observed: many Mandarese women have moved away from traditional weaving activities and increasingly participate in the fish trade. [Source: Wikipedia]

Culturally, the Mandarese share many similarities with the Bugis. Their economy traditionally centers on fisheries—particularly the production of dried, salted, and fermented fish—as well as agriculture, including coconut palms, dry rice, coffee, tobacco, and forestry products. The Mandarese are widely regarded as among the most skilled sailors in Sulawesi and have long been active in maritime transportation.

Traditional cultural expressions include a two-stringed lute and the boyang, the traditional Mandarese house. Festivals such as Sayyang Pattu’du (the dancing horse) and Passandeq (outrigger canoe sailing) remain important cultural events. In South Pulau Laut District of Kota Baru Regency, the Mandarese also practice the Mappando’esasi sea-bathing ceremony. Traditional foods such as jepa, pandeangang peapi, and banggulung tapa are characteristic of Mandarese cuisine.

Bonerate

The Bonerate people are an ethnic group in South Sulawesi that inhabit around the Selayar island group such as Bonerate, Madu, Kalaotoa, and Karompa islands, which are in the middle of the Flores Sea between Flores and Sulawesi. Also known as the Orang Bonerate, Salayar and Selayar, they are regarded as skilled boat builders and were once involved in slaving and piracy. Bonerate men still spend a lot time at sea. The Bonerate language is closely related to the language of the Tukang Besi islands off the southeast coast of Buton Island. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Bonerate are Muslims but not particularly devout ones. Ramadan is the only time mosques see many people and many people believe in spirits and ghosts.Sexually provocative behavior occurs in a possession-trance ritual practiced only by women, in which they smother glowing embers with their bare feet at the climax of the ritual.

Bonerate is a relatively inhospitable island without much water. The Bonerate raise corn, cassava, pumpkins, watermelon and other foods in the short rainy season. Sometimes water supplies run so short they have to drink relatively brackish water found near the coast. Most protein is derived from fish, and marine worms and crustaceans. Their boat building is done with remarkably low technology methods and tools that were adaptable when they switch from primarily making sailboats to motorboats. ~

In marriage, a lot of emphasis is placed on the groom marrying above his station to improve the status of his family. Marriages have traditionally been arranged and sometimes wealthy families of the bride give money to the groom’s family to help them pay off the bride price. Relations between husband and wife and men and women in general tend to be very egalitarian. The arts focuses on war dances accompanied by flute music. Occasionally there are trance dances with possessed women dressed as sea captains, babbling a language interpreted by ritual leaders. ~

Ethnic Groups in Southwestern Sulawesi

Tolaki are the major indigenous ethnic group of Southeast Sulawesi. Also known as the Lalaki, Lolaki, and Laki, they raise rice and sago and hunt deer distinguished by strong traditions, close ties to the land, and a culture centered on unity and social harmony.. Historically their society was divided into nobles, commoners and slaves and was organized into kingdoms such as Konawe and Mekongga. They speak the Tolaki language, part of the Bungku–Tolaki branch of the Austronesian family, and their livelihoods have traditionally focused on farming and forest resources. According to the Christian group Joshua Project their population was 169,000 in the early 2020s and 94 percent were Sunni Muslims though pre-Islamic animistic beliefs—especially reverence for nature and ancestral spirits—remain influential. Tolaki society includes several subgroups, such as Asera and Mekongga. Kendari is an important urban and cultural center. [Source: Google AI]

Tolaki cultural values emphasize unity, respect, and strong communal bonds, expressed through shared rituals and collective life. Most were traditionally farmers and forest gatherers, cultivating sago, rice, and maize and guided by an ethic of sufficiency often summarized as “house, sago, and fish.” Cultural life is marked by traditions such as the molulo (or lulo) dance, performed arm in arm to the sound of gongs (karandu). A central customary institution is Kalosara, which governs social order and dispute resolution, promoting peace and harmony through community participation and symbolic exchanges. Traditional attire is generally simple yet refined, often accented with symbolic gold jewelry.

Muna live on Muna Island south of the southeastern peninsula of Sulawesi. Also known as the Mina, Moenanezen, and To Muna, they have traditionally lived in plaited-grass houses on piles and raised maize, sweet potatoes and sugar and were ruled for centuries by the Butonese sultanate. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Muna population in the early 2020s was around 350,000, mostly on Muna and Buton islands, and 98.5 percent are Muslims. Appearance-wise Muna look people from Melanesia and Nusa Tenggara than Bugis and Malay Indonesia. Kite flying, known as kaghati kolope, is popular and was traditionally practiced by farmers while guarding their fields and kites, it is believed, will to transform into an umbrella and protects its owner in the afterlife. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Among the key Life-cycle rituals are the Karia ceremony for young women. Performed at around ages 15–16, it involves a 96-hour seclusion during which a mentor (pomantoto) instructs participants in social values, womanhood, parenting, and community responsibility. Completion of Karia is considered essential before marriage, and interruption of the ritual may result in social exclusion. Another important tradition is Kasambu, a ritual held during a woman’s first pregnancy, usually in the seventh or eighth month, to give thanks and pray for a safe birth. Pregnancy itself is regarded as a blessing, though expectant mothers are believed to be vulnerable to harmful influences and therefore use protective objects such as garlic or pins for spiritual safety. [Source: Wikipedia]

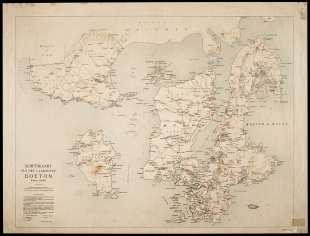

Butonese Sultanate

The Butonese sultanate shaped life and culture in southeast Sulawesi for several centuries. It was founded as a Hindu kingdom in the 15th century. The sixth king (raja) converted to Islam in 1540 and later converted the whole kingdom, which lies on the strategic route between the Spice islands and Java. The sultanates of Makassar and Termate tried to control Buton which managed to stay independent through agreements with the Dutch East India Company and later the Dutch colonial government and wasn’t completely absorbed by Indonesia until 1960. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

According to local tradition, migrants from Johore founded the kingdom of Buton in the early fifteenth century. The early rulers (raja) maintained ties with the Hindu kingdom of Majapahit in Java and were likely Hindu themselves. In 1540, the sixth raja converted to Islam, becoming the first sultan, and during his reign Islam was formally adopted throughout the kingdom.

The Butonese have traditionally been seafarers and traders. They traveled and migrated to many parts of the Indonesia, archipelago using smaller vessels ranging small ones that could only accommodate five people to large one capable of carrying 150 tons of cargo. The Butonese Sultanate lef their mark in the form of defensive architecture. The Butonese palace is the largest fortress. The Malige Palace is good example of a traditional Butonese house . It stands firmly as high as four stories without using a single nail. The currency of the Buton Sultanate was called kampua or bida.

Buton occupied a strategic position on the maritime route linking Java and Makassar with the Moluccas, the center of the spice trade. As a result, it was drawn into seventeenth-century power struggles between the sultanates of Makassar and Ternate, in which the Dutch East India Company (VOC) played a major role. Seeking to preserve its independence, Buton concluded its first treaty with the VOC in 1613, during a meeting between Sultan La Elangi and Governor-General Pieter Both. Only after Makassar was defeated by the VOC in 1667–1669 did Buton escape these rivalries and come under the Dutch-imposed Pax Neerlandica.

Throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the sultanate of Buton largely retained its independence, as Dutch colonial authority remained limited. This situation changed in the early twentieth century with the imposition of a new contract in 1906, granting the colonial government the right to intervene in internal affairs. Although still described as “self-governing,” Buton was now firmly integrated into the colonial system, leading to major sociocultural and economic changes in administration, education, health, and trade. This process of incorporation continued after Indonesian independence in 1949 and culminated in 1960 with the formal dissolution of the sultanate, shortly after the death of the last sultan.

Religions in Southeast Sulawesi

Islam is the dominant religion in the former sultanate of Buton, though religious diversity exists. Small Roman Catholic communities are found in southern Muna, while Protestant Christianity predominates in the Rumbia and Poleang districts, home to about 40,000 people. Islam was adopted and disseminated from the political center to the villages in a limited way, a strategy that helped maintain elite authority. As a result, religious knowledge in rural areas remained relatively shallow. In the center, Islam developed in a mystical or Sufi form, influenced by seventeenth-century Aceh and shaped by earlier Hindu traditions. A distinctive feature of this local Islam was belief in reincarnation, which remains strong in central Buton but was weaker in the villages, where it was regarded as part of official Islamic teaching. In recent decades, a more orthodox form of Islam has spread through state schooling and standardized Friday sermons. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Alongside Islam, traditional beliefs in supernatural beings continue to play an important role in village life. These include guardian spirits of houses, boats, and villages; spirits associated with harvests; possession spirits believed to cause illness; and benevolent spirits that offer guidance. The spirits of deceased relatives (arwah) are especially significant, as they are thought to protect the living but may also bring misfortune if disturbed.

In the former sultanate, Islamic affairs were overseen by the religious council (sarana agama or sarana hukumu), based at the central mosque (mesydid agung) in the Wolio kraton. Although the council still existed in a reduced form in the late twentieth century, its close ties to the sultan and its political role disappeared after the dissolution of the sultanate in 1960. Traditionally, Islam and customary law (adat) were closely integrated. Four of the twelve moji (or modin), known as bisa, were believed to possess spiritual power gained through ascetic practices (beramal) and were tasked with protecting the kingdom from disasters and enemies in cooperation with the sultan.

Today, the main mosque in Baubau serves as the official Islamic center of Buton, with Friday prayers and major ceremonies attended by officials and townspeople. In Muslim villages, smaller mosques (langgar) serve local religious needs, though ritual knowledge is often limited. In some areas, such as Rongi, a local religious council (satana agama) still exists. Traditional specialists with knowledge of the supernatural world continue to act as mediators in cases of illness and uncertainty.

Major Islamic holidays are observed in Muslim towns and villages, though village practices are often less elaborate and less fully understood. In the former capital, ceremonies frequently incorporate elements of traditional Butonese religion. Christian holidays are celebrated in Christian communities according to standard Indonesian church practice. Muslim funerals generally follow Islamic rites but retain traditional elements. While Butonese Muslims are familiar with Islamic teachings on judgment, heaven, and hell, belief in reincarnation remains widespread. Many people believe that deceased relatives may be reborn as children within the community, a belief that continues to shape local understandings of death and the afterlife.

Butonese

Butonese is a collective term that embraces a number of ethnic groups that live mainly in two regions on the southeastern part of Sulawesi and on the islands of Buton (Butuni or Butung), Muna, Kabaen and the Tukangbese Islands. Also known as the Orang Buton, Orang Butung, Orang Butuni, they once belonged to the powerful Butonese sultanate that was dissolved in 1960 but otherwise are difficult to define. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The former Butonese sultanate covers an area between 4° and 6° S and 122° and 125° E, spanning 11,300 square kilometers (4,362 square miles). The islands are formed from raised coral reefs and are rather mountainous. Clay plains are especially prevalent in northern and eastern Muna, northeastern Buton, and Rumbia. The easterly monsoon occurs from May to December, and the westerly monsoon occurs from December to April. ~

There are about a half million people on the islands and regions that once belonged to the Butonese sultanate: 1) Buton Regency (120,873). 2) Baubau City (161,280); 3) Central Buton Regency (121,369); 4) South Buton Regency (101,635) and 5) North Buton Regency (73,766) in the early 2020s. According to Wikipedia the total Butonese population is 233,000, with 215,000 mainly on the Tukangbesi Islands, Southeast Sulawesi and some in Maluku and West Papua provinces, and 18,000 in Malaysia, mainly in Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan and Tawau. The Christian group Joshua Project list population of Cia-Cia speakers at 94,000 and said 98 percent are Muslims.. The population of the Sultanate of Buton was estimated at 100,000 in 1878 and at 491,144 in 1980 (316,759 in Buton and 174,385 in Muna).

The Butonese language situation is complex, with two main groups. The Bungku–Mori group, related to languages of southeast Sulawesi, is spoken on Kabaena Island, in northern and northeastern Buton, and in the Rumbia–Poleang area on the Sulawesi mainland. The Buton–Muna group is used in the rest of the former sultanate and includes four languages or subgroups: Wolio, spoken mainly by the nobility and elites around Baubau and now numbering fewer than 25,000 speakers in the 1990s; Muna, spoken on Muna Island and the northwest coast of Buton; the languages of southern and eastern Buton; and those of the Tukangbesi Islands. All belong to the Austronesian language family. Historically, only Wolio was written, using Arabic script, but it has declined as Indonesian in Roman script has become dominant through schooling. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Butonese Society and Family

Many Butonese social customs and religious beliefs are in line with those of Islam. Sufism is strong and is believed to have taken root because of its similarities with Hindu beliefs that existed before the conversion to Islam. Monogamy is the rule but in the past many nobles and the sultan had several wives. There traditionally have been four classes—two classes of nobles, commoners and slaves—which still define and stratify their descendants and specify who they can marry. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Marriage in Butonese society was traditionally polygynous among the ruling elites (kaomu and walaka), especially the sultan, whose multiple marriages served political purposes. Today, most marriages are monogamous, though partner choice has long been relatively free despite strong parental involvement. First-cousin marriage is generally prohibited except among nobles, while marriage to more distant cousins may be preferred to retain family property. Newly married couples typically reside with the bride’s parents until establishing their own household.

The nuclear family is the basic domestic unit, often extended to include elderly parents, widows, or orphaned relatives. Inheritance is usually divided equally among children, though certain items are gender-specific, and the family house typically passes to the child—often the youngest daughter—who remained with and cared for the parents. Child socialization historically reflected Buton’s four-class system, with elite girls once subjected to seclusion until marriage, a practice that disappeared after World War II. Education today is equally accessible to both sexes.

Historically, Butonese society was organized into four classes: the kaomu (royal lineage), walaka (elite leaders), papara (village commoners), and batua (slaves). Slavery was abolished after 1906, and although class distinctions lost official legitimacy after independence, they continued to influence social relations informally, especially marriage. Modern education has increased social mobility, and clear socioeconomic classes remain weakly defined.

Politically, the former sultanate included several vassal states and semi-autonomous villages (kadie’) governed under customary councils (sarana). These structures gradually gave way to the modern Indonesian administrative system after colonial incorporation and independence, dividing the region into regencies, subdistricts, and villages governed by state-appointed or elected officials. In some areas, traditional councils still operate alongside modern administration. Informal social control through kinship, custom, and religion remains strong at the village level. Armed conflict largely ended after the establishment of Dutch colonial peace in the seventeenth century, with later disputes managed by colonial and then Indonesian state authority.

Butonese Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Butonese settlements have tended to be closely packed together with a high number of residences. Many have been located in defensible positions like on hills and had stone walls and other protection to defend off attacks from pirates. Some Butonese are farmers who raise rice, maize, tobacco, peanuts, cashews and other crops but mostly they are known as boat builders and prahu-based mariners and sea traders like the Bugis. In the old days they were involved in slave trading. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In the early twentieth century, most Butonese settlements were small, with about half having fewer than 500 inhabitants. Settlement patterns were either highly concentrated or widely dispersed, shaped largely by the threat of pirate attacks. Many coastal villages and those on the Tukangbesi Islands were fortified with thick stone walls, while others adopted dispersed settlement to avoid detection. Government policies during the colonial and post-independence periods encouraged village consolidation, leading by 1980 to larger and more centralized settlements, with Baubau and Raha emerging as major urban centers. Village houses were typically raised on stilts and built from sturdy wood, with roofs of palm leaves, planks, or corrugated iron.

Following the dissolution of the sultanate, most court-based arts declined, though some traditional dances are now being revived. Butonese culture has relatively few elaborate artistic traditions. Traditional medicine remains important, especially in remote villages, where healers diagnose illness through supernatural causes and prescribe rituals and herbal remedies alongside limited access to modern clinics.

The economy is based on subsistence agriculture, fishing, and trade. Staple crops include maize, tubers, and dry rice, varying by region, while tobacco, peanuts, and cashew nuts are key cash crops. Coastal communities rely heavily on fishing. Historically, the Butonese were renowned seafarers and traders, using large sailing vessels (praus) for transport and commerce; although sailing craft have declined, they have been partly replaced by motorized boats. Limited local economic opportunities have encouraged migration, often seasonally, particularly to the Moluccas for clove harvesting.

Craft production includes boat building, ritual specialization, and small-scale metalwork, pottery, and weaving, though textile production by women is decreasing. Trade is supported by local markets, peddlers, and shops, with larger commercial centers in Baubau and Raha. Labor is strongly gendered: men dominate seafaring, farming, metalwork, and boat building, while women are responsible for weaving, pottery, household work, and managing household finances. Traditionally, land was communally owned and allocated by village councils, but under modern Indonesian law land is held individually, though some descendants of former slaves remain landless.

Cia-Cia Butonese Adopt Korean Hangul to Preserve Their Language

The Cia-Cia, a Butonese group that lives in Bau-Bau, the main city on Buton Island, have officially adopted Hangul, the Korean written alphabet, to transcribe their spoken language of Cia-Cia. It is the first time that foreigners have adopted Hangul as their official writing system. According to the Hunminjeongeum Research Institute, the city began distributing textbooks written in Hangul in 2009 to 400 elementary students in the Sorawolio district where many Cia-Cia people live. [Source: hankorey, August 7, 2009]

The 60,000 member Cia-Cia tribe has been on the verge of a crisis regarding the disappearance of their language. They do not have a writing system to complement their spoken language. Members of the Hunminjeongeum Research Institute persuaded them to adopt Hangul, and established a memorandum of understanding with city officials to use Hangul on July 2008. The Hunminjeongeum Research Institute invited two persons from the Cia-Cia tribe to Seoul to create a textbook written in Hangul. The textbook includes traditional Cia-Cia and Korean stories. The Hunminjeongeum Research Institute and Bau-Bau City will build a Hangul Culture Center and plan to train teachers in Hangul. Kim Ju-won, the president of the Hunminjeongeum Research Institute, says “It is significant that Hangul can be used to prevent a minority language from disappearing.”

In 2013, the Korean Times reported: “The King Sejong Institute, which operates Korean-learning programs overseas, established a language school in Bau-Bau City on Indonesia's Buton Island in early 2012 to teach Hangeul but it was temporarily closed eight months later due to a budget shortage. The school, located inside Muhammadiyah Buton University, resumed operations in 2013 said Song Hyang-geun, chairman of the King Sejong Institute. "We've reopened language courses for the Cia Cia after resolving the financial problem," Song said. "A 27-year-old Indonesian teacher, who completed Korean teaching programs in Korea last year, will give lessons twice a week, using textbooks tailored for the minority tribe." Song also said another Korean language school will be established in Makassar City on Sulawesi Island in March. There is also a similar school in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. Song said the Cia Cia people have shown a growing interest in learning Korean since the tribe adopted the Korean alphabet to transcribe its native language in 2009. [Source: Na Jeong-ju, Korean Times, January 3, 2013]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026