SAMA-BAJAU AND THE SEA

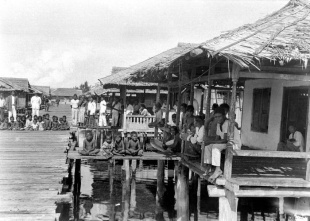

The term Sama-Bajau is used to describe a diverse group of Sama-Bajau-speaking people who are found in a large maritime area with many islands that stretch from central Philippines to the eastern coast of Borneo and from Sulawesi to Roti in eastern Indonesia. The Sama-Bajau people have traditionally been a landless people that were sustained completely and exclusively by the ocean. But not only have they survived solely on marine resources—they actually have lived in the ocean as well. Entire villages are built on stilts and connected by wooden bridges over large expanses of coral reefs and rocks in the middle of the open sea. The Sama-Bajau tribes have intimate knowledge of the maritime coastal ecosystems, as well as the seasons, winds, currents, tides, lunar cycle, stars and navigation. They are also distinguished by their exceptional free-diving abilities, and through years of practice have acquired physical adaptations that enable them to see better and dive longer underwater.

Sea-dwelling Sama-Bajau traditionally spent so much time on the water that it was said they only came ashore to die. Some still live in traditional outrigger houseboats that can be moved to different points, bury their dead on sacred islands and exchange services for spring water at coastal settlements of other groups. Their skill as sailors and gatherers of marine products enabled to the Sama-Bajau to earn a responsible amount of money providing products for trade the Chinese market. Now most are land based. The boat-based groups are found mainly in the Sulu islands and southeastern Sabah.

Understandably the diet of many Sama-Bajau people is heavy on fish and other seafood. Some fish and dive for almost everything they eat. Some live in houses on the beach or on piles in clam lagoon waters; others have no homes but their boats. [Source: Ann Gibbons, National Geographic, September 2014]

The Sama-Bajau have developed specialized boat building skills, and through expertly constructed watercrafts, are able to navigate through tricky waters in the areas where they live. They have traditionally used small wooden sailing vessels such as the perahu (layag in Maranao), djenging (balutu), lepa, and vinta (pilang) as well as medium-sized vessels like the jungkung, timbawan and small fishing vessels like biduk and bogo-katik.

In the past, the Sama-Bajau lived almost completely segregated from the “land people,” and preserved their distinct way of life for generations. In recent decades, these traditionally, sea-wandering nomads are now adapting more to a land-based lifestyle and interacting more with land-based ethnic groups. They are being encouraged to settle on land. Many aspects of the Sama-Bajau sea-based culture have been abandoned. With more and more Sama-Bajau Sama-Bajau descendants now speaking Bahasa Indonesia their ancient language is slowly dying out. Because the Sama-Bajau tend to migrate with the seasons and changing winds and ocean conditions, it is unclear how many still retain a sea-based lifestyle. The 2010 film “The Mirror Never Lies” — a collaborative effort between the WWF-Indonesia, the Wakatobi administration and SET Film Workshop, — gives insight into the lives and culture of the Sama-Bajau people and the marine biodiversity in the Wakatobi islands of Sulawesi. [Source: Indonesia Tourism]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

MOKEN SEA NOMADS: HISTORY, LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MOKEN IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

Physiological Adapation of the Sama-Bajau to Their Sea-Based Lifestyle

The Sama-Bajau are renowned for their extraordinary free-diving abilities. Divers often spend long days at sea, achieving what has been described as the greatest daily time holding one’s breath recorded in humans, frequently exceeding five hours per day underwater. To ease pressure during repeated deep dives, some Bajau deliberately rupture their eardrums at a young age, a practice that has left many older individuals partially hard of hearing. [Source: Wikipedia]

More than a millennium of subsistence free-diving linked to a maritime way of life appears to have led to biological adaptations that support this lifestyle. A 2018 study found that Bajau spleens are, on average, about 50 percent larger than those of neighboring land-based populations such as the Saluan. Larger spleens can store more hemoglobin-rich blood, which is released into circulation when the spleen contracts at depth, enabling longer breath-hold dives. This trait has been associated with a variant of the PDE10A gene.

Additional genes showing signs of selection among the Bajau include BDKRB2, involved in peripheral vasoconstriction and the diving response; FAM178B, which regulates carbonic anhydrase and helps maintain blood pH as carbon dioxide accumulates; and another gene linked to hypoxia tolerance. Together, these traits appear to reflect natural selection, resulting in a higher frequency of advantageous alleles in Bajau populations compared with other East and Southeast Asian groups.

For comparison, members of another maritime people, the Moken, have been shown to possess superior underwater vision compared with Europeans, although it remains unclear whether this ability has a genetic basis.

Sama-Bajau Society and Kinship

Sama-Bajau social and political organization varies with the group. Some groups are egalitarian. Others, often the larger ones, have a hierarchal structure with nobility and commoners, and in the past slaves. These days hereditary privileges are largely a thing of past but titles still carry prestige. Mosques are centers of social, community and religious life. Clusters and parishes are generally led by elders, cluster leaders and religion leaders. Incidents of armed conflict are relatively rate, although raids and vendettas sometimes occur. Disputes are settled with the help of cluster, parish and villages leaders. Incidents involving different groups are often settled using Islamic law. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Historically, some Sama groups—most notably the Jama Mapun, Balanguingui, and Pangutaran Sama-Bajau—enjoyed substantial trading and political autonomy within the Sulu Sultanate. Like the dominant Tausūg, these groups were socially stratified into nobles, commoners, and slaves, while other Sama communities remained more egalitarian. Among the stratified groups, the nobility—comprising datu and salip—derived wealth and influence from trade, raiding, and control over slaves and the labor of commoners. Although such hereditary privileges are no longer formally recognized, inherited titles still carry social prestige, and modern class distinctions are largely based on wealth and political influence.

Kinship among Sama-Bajau societies is strictly bilateral, along both both male and female descent lines, and knowledge of genealogy is generally shallow. There are no permanent corporate descent groups. Instead, people recognize a broad bilateral kindred, commonly referred to as the kampong, which includes all individuals regarded as kin, whether or not the precise genealogical links can be traced. Obligations to close relatives include attending funerals, weddings, and thanksgiving rites; lending or borrowing food, money, and property; and maintaining regular visits and hospitality. Kinship terminology varies across Sama-Bajau communities, but all systems emphasize lineality, generation, and relative age. Among the Jama Mapun, nobles are reported to use a Hawaiian-type kinship terminology, distinct from the more common Eskimo-type system used by commoners and other Sama groups.

Among the Jama Mapun, a more clearly defined localized kin group, known as a lungan, is recognized. Its members trace bilateral descent from a common ancestor over approximately three to eight generations. These groups form the principal base of support for local and regional leaders and provide an important framework for social cooperation. Among the Bajau Laut, close kin are distinguished both from the wider category of kin (kampong) and from non-kin, referred to as a’a saddi (“other people”). Within the kampong, individuals recognize specific descent lines (turunan), each traced to a particular ancestor. Close kindred (dampalanakan or dampo’un) minimally include those who share descent from common grandparents (mbo’), such as first cousins traced bilaterally. While descent itself carries little formal social weight, collateral ties are strongly emphasized. Mutual assistance among close kindred is considered obligatory, unless severed by formal enmity (bantah), and applies in situations such as life-cycle rituals, illness, economic hardship, legal disputes, and conflict. These close relatives typically form the core of multifamily households, household clusters, and local parish groups.

Sama-Bajau Political Organization

Political organization begins at the village cluster level and may advance to the parish and district level among larger groups. It is manifested primarily through the establishment of networks and coalitions between Sama-Bajau groups and with non-Sama-Bajau groups and governments in the countries that have jurisdiction over them. Many Sama-Bajau groups are subordinate to dominate Tausug, Maguindanao and Bugis groups. In the past some groups were treated as the property of local sultans. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The boat-dwelling Bajau Laut traditionally viewed themselves as nonaggressive and preferred avoidance over direct confrontation. Historically, they relied on shore-based patrons to shield them from regional feuding and political rivalries. As a result, dominant regional groups often regarded the Bajau Laut as timid or unreliable. While some Sama groups participated in slave raiding and were occasionally recruited by regional states as naval forces, boat-dwelling communities generally sought to remain politically neutral.

In Sulu and southeastern Sabah, the sultan of Sulu claimed proprietary rights over all boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau, usually exercised through delegated local leaders. In practice, this took the form of patron–client relationships. Shore leaders asserted “ownership” over individual moorage groups and, in return for loyalty, offered protection, anchorage sites, and access to agricultural produce. Boat-dwelling clients supplied their patrons with fish and other marine products, formerly including valuable trade items such as mother-of-pearl and trepang. If a patron failed to provide protection or imposed unfair trade terms, a moorage group could move elsewhere and align itself with a rival leader. This mobility and competition for clients limited abuses and allowed the Bajau Laut a notable degree of political autonomy.

Nevertheless, boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau traditionally lacked parish or village organizations and had no direct representation within the state, relying instead on their patrons. In contrast, shore-based and land-based Sama groups maintained their own village and regional leadership, with authority exercised through leader-centered coalitions. While these leaders held local power, they historically owed allegiance to the sultan or head of state. Their authority was legitimized through the granting of titles, integrating local communities into the wider polity. In return for tribute and loyalty, titleholders were empowered to regulate trade, levy taxes, maintain order, and administer justice. Today, such regional leaders function largely within electoral systems or state-appointed structures, serving as intermediaries between local communities and national governments in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Sama-Bajau Family

Sama-Bajau households are defined as a group that eats together and is usually comprised of a nuclear family with a few additional relatives. The division of labor is pretty equal with men specializing in boat building and iron works and women specializing in pandanus mat weaving and pottery making. Both men and women engage in trade. Among nomadic groups men have traditionally done the fishing while women engaged in inshore gathering. Inheritance is bilateral, meaning each child, regardless of sex, is entitled to a share of their parents' property. The Sama distinguish between property acquired during a marriage and property inherited independently. The latter is not subject to claims by the owner's spouse. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Family members are expected to attend funerals, children’s weddings and thanksgiving rites; lending and borrowing of property, food or money; and exchanging visits and hospitality. Children are highly valued. They undergo a ritual hair cutting and weighing ceremony. Both sexes are circumcised. Girls are circumcised between the ages of two and six in small private rituals attended only by women. Many children receive some kind of training in the Koran. Reciting the Koran is a greatly valued skill. After puberty girls are expected to stay close to home. They assist in household chores. Boys are given more freedom. They often help their fathers fishing. Children attend school but generally only for a couple of years. Three days after a child is born his father swims with him to introduce him to the sea.

Among boat-dwelling groups, each boat usually shelters a nuclear family and one or two additional relatives, averaging five or six people in all. In this setting, the family functions as both a domestic group and an independent economic unit. Among groups whose members divide their time between living in a village and dispersing at sea, domestic organization is characteristically complex. While the nuclear family functions independently at sea, upon their return to the village, its members are frequently incorporated into larger, multifamily households. These larger groups share a common hearth, meals, and residence within a single village pile house. They are identified by name with the owner as his tindug, or followers.

Among settled, shore- and land-based groups, households are often large. While most contain a single stem or nuclear family, larger groups consisting of the families of two or more married siblings are not uncommon. Each household has an acknowledged head. This head of household is usually the house owner and is most often a man still actively engaged in making a living. ~

Sama-Bajau Marriage

Sama-Bajau marriages are generally between kindred of around the same age, preferably between patrilineal, parallel cousins, and may be partially arranged by parents with the help of a go-between. The marriage may be initiated by an elopement or in some special cases by an abduction. In all cases a bride price is paid, with a particularly high one being paid in the case of an abduction.

Weddings have traditionally been the biggest and most grand Sama-Bajau gatherings. The ceremony is presided over by an imam or group of religious officials, who witness the transfer of the bride price. In a traditional weddings of boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau the groom is doused with seawater, the bride's face is painted with chalk and her eyebrows are shaped into triangles, girls dance on boats and men throw bananas at each other. The climax of the ceremony is when the father of the bride takes the finger of the groom and places it in the head of the bride and then her breasts. These days the bride often wears a white dress and the groom an Arab headpiece from Mecca. Sometimes newlyweds are pushed out to sea on a boat.

Newlywed couples may live with the bride’s or groom’s family and are expected to set up their own households by the second or third year of marriage, often with the house near the bride’s family cluster. Polygyny is allowed but rarely practiced. The frequency of divorce varies with the group, but is said to be common among some groups.

Sama-Bajau Settlements

Sama-Bajau villages generally consist of closely-clustered houses situated along well-protected stretches of shoreline. They are often built directly over the sea in channels or tidal shallows, often behind a fringing reef. Household are often grouped in clusters of related kin with their own chief. The houses are often built near of nipa near mangrove forests, where residents work as thatch- and woodcutters. Large clusters are often organized around a mosque. Schools, mosques and clinics are usually located inland. Some villages are entirely on land and even built somewhat inland.

Houses are raised on piles one to three meters above the high water mark or the ground and are usually comprised of a single room attached to a kitchen, often a room without a roof where various chores are performe. Those of poor people are typically constructed of split bamboo and have thatched roofs. Many are poorly constructed and too small to allow a person to stand up straight. Those belonging to wealthier families have timber walls and floods, corrugated metal roofing and have additional sleeping rooms. House built over the water are connected by catwalks.

Households are organized into tumpuk, or clusters, made up of adjacent dwellings whose occupants are closely related through bilateral kinship, most often siblings or the spouses of siblings. Each cluster typically recognizes one household head as its spokesperson, provided this person has the support of most members. In some cases, a cluster corresponds to a parish, defined by shared affiliation with a single mosque. More commonly, a parish includes several clusters that acknowledge a common leader in political and legal affairs, usually the mosque’s owner or sponsor. Larger villages may contain multiple parishes, with one parish leader generally recognized as the overall village head.

Lifestyle of Nomadic Sea-Dwelling Sama-Bajau

Rebecca Cairns of CNN wrote: Bilkuin Jimi Salih doesn’t remember how old he was when he learned to dive, only, that all the men in his family can do it. It might have been his grandfather who taught him, or his father, or even an uncle or cousin. He recalls swimming dozens of feet underwater among the reefs, collecting spider conches, abalone and sea cucumbers to sell at the local fish market. “One of our specialties is that, because we live on the sea and we’re always in the sea, we can dive in the water for a long time,” says Salih, a 20-year-old was born on board a lepa, a type of houseboat, on the shore of Omadal Island, off the coast of Semporna in Malaysian Borneo.“We learn by observing, and from there, we develop our own technique...We’re very comfortable in the water,” says Salih. [Source Rebecca Cairns, CNN, November 22, 2024]

Nomadic groups traditionally have been made up of communities of scattered marriage groups that return regularly to common anchorage sites. These groups were formed around family alliances of two to six closely related boat-dwelling families. who share food, pool labor and fish and anchor together and are intermarried and make regular visits to other groups. The boats they live on vary in size. The small ones are generally dugout vessels with double outriggers. Larger ones lack outriggers and have a solid keel. Both types have a roofed living area made of poles and “kaang” matting and a portable earthenware hearth used to prepare meals. Typically one nuclear family lives on each boat. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Some pile-house villages are inhabited by families who still spend long periods at sea as boat-based fishing crews but maintain permanent houses. Such settlements often represent recently sedentarized boat-nomads and are characterized by small, simply built houses, some so low that occupants cannot stand upright. More established pile-house villages are more permanent and densely clustered, often located near nipa palms and mangrove forests, which provide seasonal employment—especially during the northwest monsoon, when rough seas restrict offshore fishing. In these villages, fishing is usually conducted by all-male crews on daily or overnight trips, with men returning home to eat and sleep. Houses typically consist of a single unpartitioned room raised one to two meters above the ground or high-water mark, with an open porch or platform used as a shared work space and a kitchen at the rear.

Among boat-nomadic groups, the boats serving as family dwellings vary regionally. In northern and central Sulu, they are usually small dugout vessels with double outriggers. Farther south, in southern Sulu and southeastern Sabah, boats are larger—averaging about ten meters in length—plank-built, without outriggers, and constructed with solid keels and bow sections. All are fitted with a roofed living space made from poles and kajang matting, as well as a portable earthenware hearth, typically kept near the stern, for preparing family meals.

Historically, boat-nomadic groups possessed little or no land beyond small burial islands shared by several moorage groups. Access to fresh water sources, such as wells or springs, and limited use of the shoreline—valuable for materials like bamboo used in masts and poles—were typically granted by shore communities in return for economic services within patron–client relationships. Among shore- and land-based Sama-Bajau, corporate ownership is minimal; houses and both residential and agricultural land are held and inherited under individual tenure rights.

Sama-Bajau Villages Off Sulawesi and Borneo

Maratua Island (in the Derawan Archipelago off the north coast of East Kalimantan on Borneo) is a large tropical island partially encircling a massive lagoon on one end and fringed with sheer rocky walls and coral reefs along the other end.This giant upside down U-shaped island covers about 384 square kilometers of sandy white beaches and mangrove forests and 3,735 square kilometers of territorial waters which contain the third highest level of marine biodiversity in the world after Raja Ampat and the Solomon Islands. Maratua has a population of about 3,000 people and is divided into 4 villages, most of which come from the Bajo Tribes.

The Bajo villages of Tilamuta, Torosiaje, Popayato can be found in the Togean-Islands-Gorontalo area of Sulawesi in Indonesia. The Bajo here that still live in on boats called “Bangau”, and move around from one island to another islands and spend much time on Toro Pantai Island, where they cultivate pearls and sea grass.

Some of the Bajo people here survive solely on marine resources and live in the ocean.Entire villages are built on stilts and connected by wooden bridges over large expanses of coral reefs and rocks in the middle of the open sea. In the past, the Bajo lived almost completely segregated from the “land-people,” preserving their very distinct way of life for generations. But these once sea-wandering nomads, who have lived for centuries at sea, are now adapting to and interacting more with the land-based ethnic groups and being encouraged to settle on land.

See Separate Article GORONTALO PROVINCE factsanddetails.com

Sama-Bajau Culture

The Sama-Bajau are well known among Muslims in the Philippines for their developed dance and song traditions, percussion and xylophone music, dyed pandanus mats and food covers, and decorative wood carving (ukil). The Regatta Lepa festival in Semporna, Sabah, Malaysia is a big Sama-Bajau. Lepa refers to the houseboat in the dialect of East Coast Bajau. In this festival, Bajau people decorate their boats with colourful flags.

Sama-Bajau performing arts includes dancing, singing, and music produced xylophone, drums and gongs. A central instrument is the kulintangan, a horizontal row of seven to nine small knobbed gongs set in a wooden frame, which carries the main melody. and is typically played by women. It is accompanied by larger suspended gongs and drums, usually played by men, either on their own or to support dancing. Another important instrument is the gabbang, a wooden xylophone with about seventeen keys, also played mainly by women, either solo or alongside singing and dance. The main Sama-Bajau dance, the “daling-daling” is performed mainly at weddings. and often involves improvised exchanges of verse between men and women.

Among the Sama-Bajau crafts are dyed pandanus mats, food covers, ornaments made of shell and turtle shell, weaving and textiles, and decorative wood carving, often featured in houses, burial markers, boats and machete handles. Sama-Bajau textiles feature rectangular design elements and figurative motifs. Some men wear square head clothes known as “destar”. In the Temasuk area of western Sabah, Sama-Bajau women are known for textile weaving, especially kain mogah, long cloths with small, subdued patterns used as trade textiles and wall hangings, and destar, square men’s headcloths woven in bold rectangular patterns with brighter dyes and, at times, figurative motifs.

Nomadic Sama-Bajaus have traditionally worn no clothes before the age of 10. Some Sama-Bajau girls look like ghosts. They put white cake on their faces called borak which is made from rice, fruit and nuts that is similar to what girls in Myanmar wear. What does it do? It is a skin moisturizer.

Sama-Bajau Grave Markers (Sunduk)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Man's Grave Marker (Sunduk) made by Sama-Bajau people of the the Sulu Archipelago. Dated to the early to mid-20th century, it is made of wood and is 71.1 centimeters (28 inches) tall. A Woman's Grave Marker (Sunduk) from the same period and place is made of wood and is 118.1 centimeters (46inches) tall. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Lying between the southern Philippines and Borneo, the islands of the Sulu Archipelago have long been crossroads of cultures and artistic traditions. Perhaps the finest sculptors in the region are the Sama-Bajau, mobile sea traders who formerly lived almost exclusively on lepa (houseboats) attached to semipermanent moorings. Although they follow, or followed, a nomadic lifestyle, the Sama-Bajau bury their dead ashore in permanent cemeteries.

The majority of Sama-Bajau today are Muslim, but their art often reflects the influence and imagery of earlier indigenous religious traditions. Such influences are especially evident in their elaborate grave markers, whose imagery in some cases includes human or animal forms that are ordinarily prohibited under Islamic religious doctrine. Like Western gravestones, Sama-Bajau grave markers indicate the resting places of the dead. The markers consist of two components: the sunduk, an upright element erected over the head of the deceased, and the kubul, a low openwork fence that surrounds the gravesite. To assist deceased individuals of both sexes on their journey to the next world, where they will join the company of the ancestors (mbo'), the Sama-Bajau place offerings of cloth, coconuts, stalks of grain, and other materials on the graves and at times honor the dead with mourning songs (kalangan matai). The form of the grave markers reflects the gender of the deceased. Women 's sunduk consist of intricate openwork planks, whereas men's are cylindrical uprights, often set into separate bases in the form of stylized ships or an imals.6 Both types are embellished with elaborate ukkil (decorative carvings), such as those on the present woman's sunduk, derived from leaves, vines, buds, and geometric motifs. The budlike elements that comprise the lower left and right corners in this example depict the stylized heads of naga, snakelike supernatural beings that appear in the art and religion of many indigenous cultures in Island Southeast Asia.

The man's sunduk is a rare example in which the upright is rendered explicitly as a human figure, set in a stylized ship whose prow and stern are adorned with intricate ukkil patterns. Although it evokes the seafaring lifestyle of the Sama-Bajau, the ship here likely serves as a supernatural vehicle. It will convey the individual to the afterlife, where he will be reunited with the deceased members of his family, as described in this poetic Sama-Bajau mourning song, sung by an aged mother for her lost son:

You are gone and now I am alone.

But you are not alone.

With you in your grave are your father, brothers, and sisters.

And soon I, too, shall join you.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025