SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS

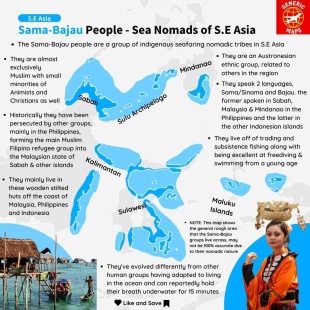

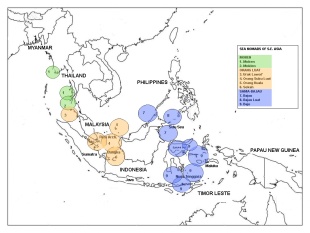

The term Sama-Bajau is used to describe a diverse group of Sama-Bajau-speaking people who are found in a large maritime area with many islands that stretch from central Philippines to the eastern coast of Borneo and from Sulawesi to Roti in eastern Indonesia. Historically, the Sama-Bajau have lacked broad political unity, with primary loyalties centered on small, localized subgroups. In the Sulu Archipelago and southeastern Sabah, communities that live on boats or have a recent history of sea nomadism identify themselves as Sama Dilaut or Sama Mandilaut (“sea Sama”). Other Sama speakers refer to them as Sama Pala’au (or Pala’u), while the Tausūg call them luwa’an. These terms often carry pejorative meanings, reflecting the marginalized status traditionally assigned to boat-dwelling peoples by settled, land-based communities. In Malaysia and Indonesia, nomadic or formerly nomadic groups are generally known as Bajau Laut or Orang Laut (“sea people”).

The Sama-Bajau are highly fragmented into diverse subgroups and have never formed a single political entity. Instead, they have typically existed under the authority of surrounding land-based polities, such as the Sultanate of Brunei, the former Sultanate of Sulu, and the Sultanate of Bone. Most subgroups take their names from their places of origin, usually specific islands. Each speaks its own language or dialect, which is generally mutually intelligible with those of neighboring groups, forming a continuous linguistic chain. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In the Philippines, most Sama speakers are referred to as "Samal," a Tausug term also used by Christian Filipinos, with the exceptions of Yakan, Abak, and Jama Mapun. In Indonesia and Malaysia, related Sama-speaking groups are known as "Bajau," a term of apparent Malay origin. In the Philippines, however, the term "Bajau" is more narrowly reserved for boat-nomadic or formerly nomadic groups referred to elsewhere as "Bajau Laut" or "Orang Laut."

RELATED ARTICLES:

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

MOKEN SEA NOMADS: HISTORY, LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MOKEN IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

Major Sama-Bajau Goups

Bajo (Indonesia) are known to the Bugis as Same’ (or simply Sama), and to the Makassar as Turijene or Taurije’n (literally “people of the water”), as well as Bayo or Bayao. These Sama-Bajau groups settled in Sulawesi and Kalimantan via the Makassar Strait from as early as the sixteenth century. From there, they spread to neighboring regions, including the Lesser Sunda Islands, the Maluku Islands, and the Raja Ampat archipelago. [Source: Wikipedia]

Banguingui (Philippines, Malaysia) are also known as Balangingi, Sama Balangingi, Sama Balanguingui, or Sama Bangingi. Indigenous to the Philippines, with some groups more recently migrating to Sabah, they are sometimes regarded as distinct from other Sama-Bajau. Historically, they were known for a strongly martial society and were once involved in organized sea raiding and piracy targeting coastal settlements and passing vessels.

Samal (Philippines, Malaysia) is a Tausūg and Cebuano term that some consider offensive. The group’s preferred self-designation is simply Sama. They are best understood as a major subgroup of the Sama Dea (“land Sama”) native to the Philippines. Many now live along the coasts of northern Sabah, while others have migrated northward to the Visayas and southern Luzon. Predominantly land-dwelling, they constitute the largest single Sama-Bajau group. The Island Garden City of Samal in Davao del Norte may take its name from this community. Samal ias also spelled Siamal or Siyamal.

West Coast Bajau (Malaysia) are also known as Sama Kota Belud. This group is native to the western coast of Sabah, especially around the Kota Belud district. They prefer the general ethnonym Sama rather than Bajau, a usage also adopted by their Dusun neighbors. British colonial administrators originally labeled them as Bajau, and the term West Coast Bajau is used in Malaysia to distinguish them from the Sama Dilaut of eastern Sabah and the Sulu Archipelago. They are particularly noted for their distinctive and enduring horse culture.

East Coast Bajau

East Coast Bajau (Philippines, Malaysia) refers to various Sama-Bajau groups living along the northern and eastern coasts of Sabah. Many members of this subgroup are regarded as native to Sabah; however, unlike the West Coast Bajau, they maintain closer cultural and historical ties with Sama-Bajau communities in the Philippines. Their population has been significantly shaped by descendants of Moro refugees, as well as legal migrants, undocumented migrants, and naturalized citizens, particularly following 1972. [Source: Wikipedia]

The East Coast Bajau are generally divided into two broad categories: the fully sedentary Bajau Daratan Pinggir Pantai or Bajau Darat (“seashore” or “land Bajau”), and the semi-nomadic Bajau Laut (“sea Bajau”). The seashore Bajau tend to distinguish themselves from the Bajau Laut, who are sometimes labeled with the pejorative term Pala’u. The land-based group comprises several Bajau sub-ethnic communities, including the Bajau Kubang, Bajau Ubian, Bajau Simunul, Bajau Sengkuang, and others.

Bajau Laut often identify themselves as Sama Dilaut. They historically maintained a boat-dwelling lifestyle. While some continue this tradition, many have since settled on land. Seashore Bajau groups, such as the Bajau Kubang, are known for constructing lepa houseboats, which are then sold to the Bajau Laut for use as mobile homes. The East Coast Bajau are also renowned for the colorful annual Regatta Lepa festival, held from 24 to 26 April, celebrating their maritime heritage.

Ubian

Ubian (Philippines, Malaysia) are also known as the Obian. They trace their origins to South Ubian Island in Tawi-Tawi, Philippines. Today, they form sizeable minority communities around several towns in Sabah, Malaysia, including Kudat (where they constitute a majority on Banggi Island), Semporna, Kota Kinabalu (notably on Gaya Island), and Kota Belud (in areas such as Kampung Baru-Baru and Kuala Abai). In Sabah, they are classified within the East Coast Bajau subgroup and can be further distinguished by two major waves of migration. [Source: Wikipedia]

The first group consists of Ubian who arrived in Sabah before World War II, with one of the earliest documented accounts dating to 1888. Over time, their descendants became acculturated into local Sabahan society, including elements of West Coast Bajau culture. Under Sabah’s constitutional framework, they are recognized as natives of the state, as many were born in Sabah during the colonial period.

The second group comprises Ubian who arrived from the southern Philippines beginning in 1972 as asylum seekers fleeing the Moro Conflict. This group has generally been regarded by many Sabahans as undocumented migrants or foreigners. However, a significant number later obtained Malaysian identification cards, a process often associated with the controversial Project IC in Sabah. Despite these circumstances, descendants of this second migration wave who hold Malaysian identification have increasingly integrated into local Malaysian and Sabahan society and commonly regard themselves as citizens of the country.

Non-Sama People That Speak Sama Languages

The following groups are culturally related to the Sama people and speak languages within the Sama–Bajau linguistic family, but they do not generally identify themselves as Sama. [Source: Wikipedia]

Abaknon (Philippines) are a community from Capul Island in Northern Samar, in the Visayas. Also known as the Abak, they speak the Abaknon language and were early subjects of Spanish colonization, converting to Christianity at an early period and becoming culturally Visayan. According to their folk history, their ancestors originated in the southern Philippines—identified in some accounts as Balabac Island. Oral tradition holds that, during the fourteenth century, they refused to convert to Islam or submit to the authority of the Moro sultanates. Led by a datu named Abak, they left their homeland and eventually settled on what is now Capul Island.

Jama Mapun (Philippines, Malaysia) are sometimes referred to by the exonyms Sama Mapun, Sama Kagayan, Bajau Kagayan, or simply Kagayan, They originate from Mapun Island in Tawi-Tawi (formerly Cagayan de Sulu). Some members of this group have migrated to Sabah, particularly to areas such as Banggi Island and Sandakan. Their culture has been strongly shaped by historical ties to the Sulu Sultanate. Relatively isolated, they generally do not regard themselves as Sama.

Yakan (Philippines) inhabit the mountainous interior of Basilan Island. Although they may share ancestral links with the Sama-Bajau, they have developed distinct linguistic and cultural identities and are usually considered a separate ethnic group. The Yakan are entirely land-based, with farming as their primary livelihood, and are also known for a strong horse-riding tradition similar to that of the West Coast Bajau. They are especially renowned for their elaborate weaving. Historically, the Yakan resisted Tausūg domination during the early formation of the Sulu Sultanate and eventually gained recognition as a separate political entity. They are only partially Islamized, with a significant minority maintaining indigenous anito beliefs or practicing forms of folk Islam.

The Abaknonof Capul Island, northwest of Samar in the central Philippines, are the most divergent subgroup of Sama, both culturally and linguistically. The Abaknonare believed to have descended from an early northward migration of Sama speakers, and they are the only Christianized subgroup of the Sama today. The Yakan of Basilan Island and the coastal Zamboanga region are thought to be descendants of another early offshoot community. Unlike the majority groups, the Yakan-speaking groups acknowledge the symbolic suzerainty of the Tausug and Maguindanao sultanates but are today an inland agricultural people with no close ties to the sea. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Sama-Bajau in the Philippines

In the southern Philippines the term "Bajau" is reserved exclusively for boat-nomadic or formerly nomadic groups, while more sedentary Sama speakers are referred to as "Sama-Bajau," a name applied to them by the neighboring Tausug, but used also by Christian Filipinos.

In the Philippines, the Sama-Bajau are commonly divided into three broad groups based on settlement patterns. 1)The Sama Bihing, 2) Sama Dea and 3) Sama Dilaut. The Sama Bihing or Sama Lipid (“shoreline” or “littoral Sama”) traditionally lived in stilt houses along coasts and in shallow waters. Originating largely from the larger islands of Tawi-Tawi, groups such as the Sama Simunul often adopted flexible livelihoods, engaging in farming when land was available and acting as intermediaries in trade between sea-dwelling Sama Dilaut and land-based peoples.

The Sama Dea, also known as Sama Deya, Sama Dilaya, or Sama Darat (“land Sama”), traditionally lived in island interiors. Groups such as the Sama Sibutu and Sama Sanga-Sanga practiced farming, cultivating rice, sweet potatoes, cassava, and coconuts using traditional slash-and-burn methods. Originating mainly from the larger islands of Tawi-Tawi and Pangutaran, they often distinguish themselves sharply from the Sama Dilaut.

The Sama Dilaut, also called Sama Mandilaut, Sama Pala’u, or Bajau Laut, are the “sea” or “ocean Sama.” In the Philippines, Sama Dilaut is the preferred ethnonym, Traditionally, they lived almost exclusively on elaborately built houseboats known as lepa, though most have since settled on land in the Philippines, particularly on islands such as Sitangkai and Bongao. This subgroup is most frequently labeled “Bajau” or “Badjao,” terms that many Filipino Sama Dilaut consider offensive. To distinguish themselves from land-based groups, they sometimes refer to themselves as Sama To’ongan (“true” or “real Sama”). Recent studies suggest that the Sama Dilaut of the Philippines also show evidence of Indian or South Asian ancestry.

In addition to these major groupings, numerous smaller Sama-Bajau subgroups are named after their islands of origin, including the Sama Bannaran, Sama Davao, Sama Zamboanga Sikubung, Sama Tuaran, Sama Semporna, Sama Sulawesi, Sama Simunul, Sama Tabawan, Sama Tandubas (or Sama Tando’ Bas), and Sama Ungus Matata.

History of the Sama-Bajau in the Sulu Islands and Southern Philippines

The Maranao epic Darangen records that one of the ancestors of the hero Bantugan was a Maranao prince who married a Sama-Bajau princess. Dated to around AD 840, this episode is regarded as the earliest written reference to the Sama-Bajau and supports the view that they predate the arrival of the Tausūg and are indigenous to the Sulu Archipelago and parts of Mindanao (Sather 1993).

As the Sama expanded, they came to occupy a wide range of ecological niches, from land-based communities to strongly sea-oriented groups. With the rise of Tausūg hegemony in Sulu from the 13th century, this diversity narrowed. The dominant Tausūg absorbed many of the more land-oriented Sama, especially in Siasi and eastern Jolo, leaving the Sama numerically concentrated mainly in the smaller, largely coralline islands at the northern and southern ends of the archipelago.

The establishment of the Sulu Sultanate in the 15th century, together with the growth of regional maritime trade, accelerated the dispersal of Sama speakers. Some settled along the western coast of Sabah under the loose authority of the Brunei Sultanate, while others moved eastward through the Makassar Strait to southern Sulawesi. Later, as Jolo developed into a major Tausūg-controlled slave entrepôt, Sama-Bajau communities—particularly those based in the Balanguingui Islands and along the southern coasts of Mindanao—became prominent participants in maritime raiding. From strongholds such as Balanguingui Island, they carried out annual raids across a vast area, from Luzon to the central Moluccas.

The Sama-Bajau first entered European records in 1521, when Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan–Elcano expedition encountered them in what is now the Zamboanga Peninsula, noting that they “make their dwellings in boats and do not live otherwise.” In 1848, Spanish forces destroyed the principal Sama-Bajau bases on Balanguingui Island, and by the end of the 19th century European intervention had effectively ended the Sulu Sultanate’s independence. Under American colonial rule after 1899, the sultanates of Sulu and Mindanao lost their secular authority and were brought under direct administration from Manila, although resistance to central control persisted.

From the early 1970s, the Sulu Archipelago became a major arena of secessionist conflict. The resulting violence and instability caused large-scale displacement: tens of thousands of Sama migrated or fled to Zamboanga, Tawi-Tawi, and the Sibutu Islands, or crossed into eastern Sabah in Malaysia. At the same time, many Tausūg moved out of conflict centers such as Jolo and Siasi into formerly Sama-dominated areas, pushing additional Sama communities westward into Sabah. Their arrival as refugees has since added strain to an already fragile balance of ethnically based political relations.

Sama-Bajau Economic Activity in the Philippines

In the Sulu Islands and the southern Philippines nearly all locally available fish species are exploited, using a wide array of fishing techniques and gear, including handlines and longlines, lures and jigs, fish traps, spears and spearguns, driftnets, and, in some cases, explosives. In addition to fish, people collect shellfish, crustaceans, turtle eggs, sea urchins, and edible seaweeds. Farm and residential land is held under individual use or tenancy rights. While fish-trap sites, liftnet locations, and coral fish corrals may be individually owned, most fishing grounds remain open for common use. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Crews for driftnetting and handline trolling are typically drawn from the cluster members of the net or boat owner. Today, fishing is overwhelmingly market-oriented. Catches are sold through local vendors, to wholesalers—many of whom are Sama—or to carriers who transport fish to nearby retail markets. Part of the catch, usually dried or salted, is sold to larger dealers for export beyond Sulu and eastern Sabah. The principal food crops include cassava, dry rice, maize, and bananas, supplemented by yams, beans, tomatoes, onions, ginger, sugarcane, and a variety of fruits.

Shore- and land-based communities often specialize in particular trades or crafts. Some settlements function as centers of boatbuilding, pottery production, weaving, blacksmithing, or interisland trade and transport. Other specialized activities include the manufacture of kajang mats and roofing, pandanus mats, sunhats and food covers, shell bracelets and tortoiseshell combs, lime and salt production, as well as skilled carpentry and woodcarving.

Historically, different Sama groups developed reputations for distinct crafts and commercial skills. The Laminusa Sama-Bajau, for example, are renowned for the high quality of their pandanus mats, while the Sibutu Sama-Bajau are widely regarded as expert boat builders. Pottery making, particularly in Sulu, has traditionally been an exclusively Sama-Bajau craft.

Trade has long been central to Sama economic life. European accounts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries already describe Sama communities as dependent on trade even for basic food supplies. Across Sulu and eastern Indonesia, maritime-oriented groups were valued for their navigational expertise and for supplying trepang, dried fish, pearls, pearl shell, and other marine trade goods. Specialized Sama groups also engaged in intercommunity barter, exchanging fish for items such as kajang matting, cassava, and seasonal fruits, often involving both Sama and non-Sama partners. Today, most trade in fish, agricultural produce, fruit, and crafts is conducted through established local markets, while copra and, to a lesser extent, dried and salted fish are handled by larger-scale wholesalers. Historically, Sama-Bajau traders dominated the coastal trade of the Subanun along the Zamboanga coast, while in Palawan the Jama Mapun maintained similar trading relationships with swidden-farming communities in the island’s interior.

Sama-Bajau in Borneo

In Malaysia, Bajau Laut is the preferred ethnonym for the Sama-Bajau, In Borneo in Malaysia and Indonesia the term "Bajau" is applied to both boat-nomadic and sedentary populations, including some land-based, primarily agricultural groups with no apparent history of past nomadism. Communities of mixed Sama-Bajau and Tausūg heritage are sometimes known in Malaysia as Bajau Suluk, and individuals of multiple ethnic backgrounds may use compound identities such as “Bajau Suluk Dusun.” [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In Indonesian Borneo settlements are present near Balikpapan in East Kalimantan, on Maratua, Pulau Laut, and Kakaban, and in the Balabalangan islands off the eastern Borneo coast. In Sabah (Malaysia) the Sama-Bajau are present along both the eastern and western coasts of the state and in the foothills bordering the western coastal plains, from Kuala Penyu to Tawau on the east. In Sabah, boat-nomadic and formerly nomadic Bajau Laut are present in the southeastern Semporna district, while Sulu-related groups are found in the Philippines in small numbers from Zamboanga through the Tapul, western Tawitawi, and Sibutu island groups, with major concentrations in the Bilatan Islands, near Bongao, Sanga-Sanga, and Sitangkai. ~

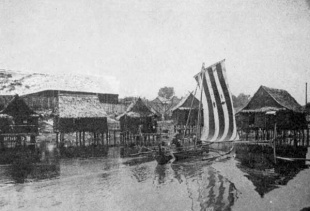

Semprona (off the eastern coast of Sabah) is famed for dazzling blue water and for being the home of large numbers of Sama-Bajau. There are hundreds of stilt homes set in shallow water, where seaweed is grown on monofilament lines and sold for canned pet food. The homes sometimes are washed away in heavy storms. Some Sama-Bajau live in sprawling stilt villages over the water on the outskirts of town. Mabul Island (accessible by boat from Semporna) is located in the clear waters of the Celebes Sea off the mainland of Sabah and is surrounded by gentle sloping reefs two to 40 meters deep. Covering some 21 hectares it is considerably larger than the nearby Sipadan Island and is home to Sama-Bajau.

See Separate Article SABAH (NORTHEASTERN MALAYSIAN BORNEO) factsanddetails.com

History of the Sama-Bajau in Borneo

The Sama-Bajau are believed to have begun dispersing from their homeland in the southern Philippines. Most moved southward into other islands and westward towards Borneo, . According to legend the event was triggered by the loss or abduction of a princess. One widely told version, especially among Sama-Bajau communities in Sabah, traces their origins to royal guards from Johor who were escorting a princess, often named Dayang Ayesha, to marry a ruler in Sulu. According to the legend, the Sultan of Brunei fell in love with her, attacked the entourage at sea, and took the princess as his wife. Rather than return in disgrace to Johor, the escorts are said to have settled in Borneo and the Sulu region. In Sabah, this narrative is particularly significant because it affirms Malay ancestry and Islamic legitimacy, reinforcing Sama-Bajau claims to Bumiputera status. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The founding of the Sulu Sultanate in the 15th century and the expansion of maritime trade accelerated Sama-Bajau dispersal. Some groups settled along the western coast of Sabah under the loose suzerainty of the Brunei Sultanate, while others moved eastward through the Makassar Strait to southern Sulawesi. By the late 18th century, Sama-Bajau communities were already well established across northern Borneo, Sulawesi, and eastern Borneo, as recorded by European visitors such as Thomas Forrest in the 1770s and Spencer St. John in the mid-19th century.

In northern Borneo, Sama-Bajau societies were integrated into overlapping political spheres. On the west coast of Sabah, they fell under Bruneian influence and in some areas maintained close relations with Illanun groups, occasionally participating in slave-raiding expeditions during the 18th and 19th centuries. Along the southeastern coast, they were part of the Sulu maritime zone, dominated by the Tausūg rulers of Jolo. Colonial rule reshaped these arrangements: in 1878, the sultans of Sulu and Brunei ceded Sabah to the British North Borneo Chartered Company, and in 1915 the Sultan of Sulu relinquished his remaining secular authority to American colonial administrators.

During the British period, the Sama-Bajau took part in resistance movements against colonial rule, notably the Mat Salleh rebellion (1894–1905) and the Pandasan Affair (1915). Colonial administration also disrupted older systems of trade and hierarchy, abolished slavery, curtailed raiding and piracy, and introduced new Chinese and European commercial interests. After Sabah joined Malaysia in 1963, the Sama-Bajau—despite being a numerical minority—emerged as a politically influential Muslim community within the state.

From the early 1970s, renewed conflict in the Sulu Archipelago caused widespread displacement. Tens of thousands of Sama-Bajau fled or migrated to Zamboanga, Tawi-Tawi, and the Sibutu Islands, or crossed into eastern Sabah. At the same time, Tausūg populations moved from conflict zones such as Jolo and Siasi into formerly Sama-dominated islands, pushing many Sama-Bajau further westward into Sabah. Their arrival as refugees has since placed additional strain on already fragile, ethnically defined political balances in the region.

Despite having lived in the region for decades, and in some cases centuries, many Bajau Laut in Semporna in Malaysian Borneo remain effectively “stateless” and are not recognized as Malaysian citizens. As a result, they exist in a state of legal uncertainty, with little or no access to public education, healthcare, or basic services such as electricity, clean water, and waste management. Reliable data on stateless populations in East Malaysia are scarce, but a recent census estimated that about 28,000 Bajau Laut live in Sabah, roughly 78 percent of whom lack official documentation. The stigma attached to statelessness often excludes them from environmental protection initiatives, and their traditional ecological knowledge is frequently overlooked or undervalued. Faced with insecure housing, limited income, and food shortages—and lacking formal citizenship—many coastal residents do not see themselves as stakeholders in conservation efforts in their area. Some young Bajau Laut, they do not wish to follow earlier generations into a lifetime of fishing. [Source Rebecca Cairns, CNN, November 22, 2024]

Economic Activity of the Sama-Bajau in Borneo

In Sabah, where the Sama-Bajau constitute less than 20 percent of the total population, they account for more than two-thirds of the state’s fishermen. With the exception of the Bajau Laut, however, most Sama-Bajau communities display considerable economic flexibility, turning to farming where land is available or engaging in a variety of other occupations. In western Sabah, the majority of Sama-Bajau settlements lie inland from the immediate coastline, mainly along the lower reaches of rivers draining the western coastal plains. Here most people farm, trade, and raise water buffalo, cattle, and horses. Some also travel inland each year to assist interior communities with rice harvesting, receiving a share of the crop in return. Among agricultural or partially agricultural groups, the principal subsistence crops are rice, cassava, maize, and bananas, while copra and fruit are grown as cash crops. Fishing communities, by contrast, are typically situated near coral reefs, submerged terraces, bays, channels, or sheltered inshore waters protected by fringing reefs, islands, or coastal headlands. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Across much of eastern Sabah, copra has long been the main cash crop, providing both income and start-up capital for other commercial activities such as shopkeeping and interisland transport. Holdings are generally small, however, and few households possess enough coconut palms to rely solely on copra sales for their livelihood.

Historically, economic specialization in most regions was closely tied to patterns of intercommunity trade. In the Semporna District of Sabah, for instance, the Sama Banaran traditionally produced kajang matting and collected resin used for caulking boats, which they traded locally with neighboring groups. Sama Kubang villages, in contrast, became known for boat building, ironworking, and the manufacture of tortoiseshell combs and ornaments, as well as carved wooden grave markers.

In western Sabah, Sama-Bajau communities historically maintained extensive trade relations with inland Dusun groups, exchanging dried fish, salt, lime, shell ornaments, and other coastal products for rice, fruit, tobacco, and forest and agricultural goods. From this exchange developed a network of periodic markets, or tamu, held at intervals ranging from five to twenty days. In more recent times, on both sides of the Philippine border, smuggling has emerged as a profitable livelihood for those with sufficient capital and the necessary commercial connections.

Sama-Bajau in Indonesia

In the eastern Indonesia the Sama-Bajau are called "Bajo" by the Bugis and both "Bajo" and "Turijene'" (people of the water) by the Makassarese. The most common term of self-designation is "Sama" or "a'a Sama" (a'a, "people"), generally coupled with a toponymic modifier to indicate geographical and/or dialectal affiliation.

In eastern Indonesia the largest numbers are found on the islands and in coastal districts of Sulawesi. Here, widely scattered communities, most of them pile-house settlements, are reported near Menado, Ambogaya, and Kendari; in the Banggai, Sula, and Togian island groups; along the Straits of Tioro; in the Gulf of Bone; and along the Makassar coast. Others are reported, widely scattered, from Halmahera through the southern Moluccas, along both sides of Sape Strait dividing Flores and Sumbawa; on Lombok, Lembata, Pantar, Adonara, Sumba, Ndao, and Roti; and near Sulamu in western Timor.

In Indonesia’s Wakatobi regency, the specialist knowledge of the Sama-Bajau has been utilized in the creation of a national marine park.“They’re very well immersed in fishing grounds and seasonality, the migration of fish, but they’re also very well aware of areas that are damaged or depleted. They know very much about navigation, currents, and upwelling areas,” says Rili Djohani, director of Coral Triangle Center, an NGO, told CNN. “It’s maritime wisdom that you can actually build upon in terms of designing, for example, marine protected areas around critical habitats, like fish aggregation areas or coral reefs.” [Source Rebecca Cairns, CNN, November 22, 2024]

History of the Sama-Bajau in Indonesia

According to Sama-Bajau legend, their movement from a homeland in the southern Philippines around the first century AD was set in motion by the loss or abduction of a princess. Among Indonesian Sama-Bajau, oral traditions place particular emphasis on ties with Sulawesi and the Sultanate of Gowa. In these accounts, a royal princess is swept away by a flood, later found, and married to a king or prince of Gowa, with her descendants becoming the ancestors of the Indonesian Sama-Bajau. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The founding of the Sulu Sultanate in the 15th century, together with the expansion of regional maritime trade, appears to have accelerated the southward and westward spread of Sama speakers. Some groups settled along the western coast of Sabah under the loose authority of the Brunei Sultanate, while others moved eastward through the Makassar Strait to southern Sulawesi. From Sulawesi, further dispersal across eastern Indonesia took place largely within the last 300 years, closely tied to the rise of the trepang (bêche-de-mer) trade and the growing political and commercial influence of Bugis and Makassarese traders.

From Sulu and eastern Borneo, additional migrations carried Sama-Bajau eastward to coastal Sulawesi and onward into the Moluccas. Dutch sources recorded Sama-Bajau communities in Sulawesi as early as 1675, and they were later noted in Sulawesi and eastern Borneo by Thomas Forrest in the 1770s. By the early 17th century, Dutch accounts already described large Sama-Bajau populations around Makassar. After Makassar’s defeat by Dutch and Bugis forces in 1669, many of these communities dispersed to other islands in eastern Indonesia.

By the early 18th century, Sama-Bajau fleets were undertaking fishing and trepang-collecting voyages as far south as Roti and Timor. Contemporary accounts from this period describe them as strongly maritime peoples, often operating as sea-going dependents of Bugis or Makassarese patrons. For nearly two centuries, the Sama-Bajau served as the principal collectors of trepang throughout eastern Indonesia, supplying a trade driven by Chinese demand.

In Sulawesi, the harbor of Bajoe was home to a Sama-Bajau settlement under the Bugis Sultanate of Bone. These communities were drawn into regional conflict during the First and Second Bone Wars (1824–1825), when Dutch colonial forces launched punitive expeditions against Bugis and Makassarese resistance. Following the defeat of Bone, most Sama-Bajau resettled elsewhere in Sulawesi.

Since Indonesian independence, change has been rapid. Government policies have encouraged the abandonment of boat-nomadism, and today most Indonesian Sama-Bajau are shore-based, living in coastal villages and relying primarily on fishing, trade, and other maritime activities for their livelihoods.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025