ORANG LAUT

Orang Laut are several seafaring ethnic groups and tribes living around Singapore, Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian Riau Islands. The Orang Laut also known as the Orang Biduanda Kallang and are commonly identified as the Orang Seletar from the Straits of Johor, but the term may also refer to any Malayic-speaking people living on coastal islands, including those of the Mergui Archipelago in Myanmar and Thailand, commonly known as Moken.[Source: Barbara S. Nowak,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Orang Laut is a Malay term that laut literally means 'sea peoples'. They have traditionally lived and traveled in their boats on the sea and made a living from fishing and collecting sea products. Another Malay term for them, Orang Selat (literally 'Straits people'), was brought into European languages as Celates. In the story The Disturber of Traffic by Rudyard Kipling, a character called Fenwick misrenders the Orang Laut as "Orange-Lord" and the narrator character corrects him

Sea-dwelling Orang Laut once roamed a large area but are now gone or mostly gone or have taken up life on land. Skeat and Ridley reported that there were only eight Orang Laut families left out of the 100 families removed from Singapore to Johor in 1847. The Orang Laut population in the 2000s was is estimated to be 420,000 people, nearly all land-based people. 1983 population figures for Orang Laut in Malaysia included 1,924 Desin Dolaq and 542 Orang Selitar. Figures for Riau-Lingga, Bangka, and Billiton Orang Laut are unknown.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOKEN SEA NOMADS: HISTORY, LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MOKEN IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS OF MALAYSIA): LIFE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

SENOI: HISTORY, GROUPS, DREAM THEORY factsanddetails.com

TEMIAR: HISTORY, SOCIETY AND RICH RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MALAYSIA: HARMONY, DISHARMONY, GOVERNMENT POLICIES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

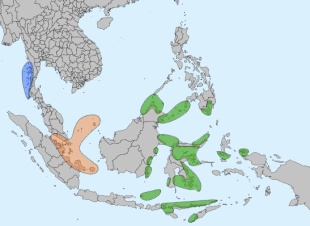

Where the Orang Laut Groups Lived

Broadly defined, the term Orang refers to the many tribes and groups inhabiting the islands, estuaries, and coastal waters of the Riau Archipelago, the Pulau Tujuh Islands, the Batam Archipelago, and the shores and offshore islands of eastern Sumatra, the southern Malay Peninsula, and Singapore. [Source: Barbara S. Nowak,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Along the Pontian coast of the Malay Peninsula live the Desin Dolaq (also known as Orang Kuala or Duano) and the Orang Seletar (Selitar or Sletar), Orang Laut communities that the Malaysian government classifies as part of the Orang Asli population. In Singapore Harbor, the Selat historically lived on Pulau Brani. Other Johor–Singapore Orang Laut communities documented in the past but now extinct or no longer identifiable include the Orang Akik, Sabimba, and Orang Biduanda Kallang. With the establishment of Port Swettenham, the British relocated the Sabimba and Biduanda Kallang inland to areas in Johor.

Orang Laut groups from the wider Riau–Lingga Archipelago include the Orang Tambusa, Galang, and Mantang, originally from the Pulau Mantang islands south of Pulau Bintan; the Orang Moro from Pulau Sugi Bawah in the Riau Archipelago; and the Orang Pusek (Persik), Orang Barok, and Orang Sekanak from Singkep in the Lingga Archipelago. The sea nomads of Bangka and Belitung Islands are represented by the Orang Sekah (also known as Sekak, Sekat, or Sika).

Communities related to the Johor–Singapore and Riau–Lingga Orang Laut are also found along the southeastern coast of Sumatra. For example, the Desin Dolaq migrated from Pulau Bengkalis and, until the Second World War, regularly visited their relatives near the mouth of the Siak River.

Orang Laut History

Historically, the Orang Laut played pivotal roles in the maritime polities of Srivijaya, the Sultanate of Malacca, and the Sultanate of Johor. They patrolled surrounding sea lanes, repelled pirates, guided traders to their patrons’ ports, and helped maintain their rulers’ dominance over regional trade routes. In exchange, Orang Laut leaders were rewarded with prestigious titles and valuable gifts. One of the earliest known descriptions of the Orang Laut may come from the fourteenth-century Chinese traveler Wang Dayuan, who wrote about the inhabitants of Temasek (present-day Singapore) in his Daoyi Zhilüe. [Source: Barbara S. Nowak,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Orang Laut oral traditions and reconstructions of historical sources trace their origins to the southern reaches of the Strait of Malacca, pointing to long-standing cultural and historical links with the Jakun of Peninsular Malaysia. Their histories frequently recount episodes of Malay slave raiding and exploitation, which are said to have driven their formerly settled ancestors to take to the sea and adopt a nomadic maritime way of life. A trait repeatedly noted in accounts of the Orang Laut is their wariness of outsiders and a tendency to flee rather than confront them.

The transformation of sea nomads into more settled coastal fishing communities—absorbing the cultural features of locally dominant societies and accelerating over the past century—has deep historical roots. The Orang Laut’s mobility and episodic patterns of settlement played an important role in transmitting and diffusing “Malay” cultural traits across the region.

Traditionally, all sea nomads spoke non-Malay Austronesian languages and dialects. Today, the few Orang Laut communities that retain a distinct cultural identity generally speak Malay, though with characteristic pronunciation. When Baptist missionaries established a school among the Orang Laut in 1946, they even produced a written primer specifically for the Orang Laut language.

Orang Laut in Singapore

When the British arrived in Singapore in 1819 they believed Singapore was uninhabited but in fact the island was used by the Orang Laut, who were highly skilled seafarers with intimate knowledge of local waters, at least as a temporary residing place. In 1819 Orang Laut communities lived in Singapore and along the nearby Johor coast. One such group, the Suku Gelam from the Batam Archipelago, maintained a settlement of boats and huts near the mouth of the Singapore River, close to a Malay kampong. Both the Malays and the Orang Laut were under the authority of a temenggung, who was himself subject to the Viceroy of Riau. The Suku Gelam served the temenggung as boatmen and fish suppliers, and their headman acted as his messenger. After Singapore was established as a British trading post, some Orang Laut relocated to the seafront at Telok Saga and Selat Sinkheh on Pulau Brani, a small island off Singapore. [Source: Mazelan Anuar, National Library of Singapore]

The earliest references to the Orang Laut appear in an account written by a Chinese traveler who visited Singapore in the fourteenth century, centuries before the British arrived in 1819. Singapore’s Orang Laut communities included the Orang Seletar, who lived among the mangroves near the Seletar River; the Orang Biduanda Kallang from the Kallang River; the Orang Gelam at the mouth of the Singapore River; and the Orang Selat from the Southern Islands. Other Orang Laut groups also lived on houseboats in the waters of southern Peninsular Malaysia and Indonesia’s Riau Islands. Nearby in Indonesia, the Orang Galang were well known as skilled rowers serving the Sultan of Palembang. [Source: Wee Ling Soh, BBC, August 25, 2021]

The Orang Laut traditionally depended on the sea for survival. In the Singapore area they traditionally gathered and hunted in mangrove forests, fished in rivers and coastal waters, and relied on plants and seafood to treat illness and injury. Life required constant adaptability, with an intimate understanding of tides and seasons. Food was not merely sustenance but central to their culture and daily existence.

Over time, Orang Laut were gradually assimilated into Malay society. Following their conversion to Islam, they came to be ethnically identified as Malay. Subsequent development projects led to the demolition of their villages and settlements, and many Orang Laut were relocated to public housing estates across Singapore. Pulau Sudong, an island off Singapore’s southern coast, was once inhabited by the Orang Laut. Today it is a restricted military training area. Singapore’s last Orang Laut settlement, on Pulau Seking, was demolished in 1993, and the island was later merged with Pulau Semakau to form a landfill.

Orang Laut Groups in the Singapore Area

From the early nineteenth century, the Orang Laut group, the Orang Seletar, occupied the shores of the Old Strait north of Singapore and the mouth of the Seletar River. Often described as river or boat nomads, they lived mainly on their boats but relied on mangrove forests and shorelines for food, hunting wild pigs with dogs. Malays referred to them as Orang Utan Seletar, or “People of the Seletar Forest.” The Orang Seletar fell under the political protection of the Sultan of Johor, to whom they historically rendered economic services. [Source: Mazelan Anuar, National Library of Singapore]

The Orang Kallang lived “since time immemorial” in the mangrove swamps along the Kallang River and formed one of the tribal groups within the temenggung’s following in early Singapore. Although nomadic, they established fixed fishing stakes near the river mouth. After 1819, many became boat rowers, ferrying passengers between ships and port. They also processed nipah palm leaves into cigarette wrappers and collected mangrove wood for fuel. Initially traveling in large vessels known as nadih, they later shifted to smaller sampan as fishing became their primary livelihood. During the twentieth century, Orang Kallang communities were dispersed to southern offshore islands, the northern coast of Singapore Island, including Tanjong Irau and Punggol, and areas such as Geylang.

The Orang Selat, or “Straits People,” had navigated the waters around Singapore’s southern coast and occupied its coastal niches since at least the sixteenth century. Primarily seafarers, they sometimes traded fish and fruit with passing ships. During the Emergency in 1948, curfews disrupted their night-time fishing activities along the southern coast of Johor, prompting many to move to Singapore’s northern coast. They maintained extensive kinship ties with communities on Singapore’s southern islands, including Pulau Semakau, Pulau Seraya, and Pulau Sudong, all of which had long been inhabited by Orang Laut. With their livelihoods threatened by curfews, the Orang Selat sought and received permission from the Punggol headman to cross the Tebrau Strait into Singapore.

Orang Laut Religion and Their Assimilation with Malays

Traditionally, Orang Laut belief systems were rooted in animism and closely aligned with the wider ideological world of Malaysia’s Orang Asli, the original inhabitants of Malaysia. . They believed in a powerful spirit world governing the sea, weather, health, and misfortune. Illness was often attributed to malevolent spirits or curses, and healing was the domain of shamans (often called bomo), who were highly respected ritual specialists. In ceremonies reminiscent of those practiced by groups such as the B’tsisi’ and Jah Hut of the Malay Peninsula, shamans were believed to extract pain or illness-causing spirits from the sick and entice them into carved figures, which were later discarded to remove the affliction. [Source: Barbara S. Nowak, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993l Google AI]

Over time, outside religious influences filtered into Orang Laut communities to varying degrees. Islamic, Christian, and Buddhist elements entered local belief systems, though unevenly. Islam became the dominant influence for most Orang Laut groups in Malaysia and Indonesia, while the Moken of the Mergui Archipelago in Myanmar and Thailand were notable as the only group largely untouched by Islam. Even among Islamized communities, religious observance varied widely, ranging from nominal Muslims—some of whom continued to eat pork or did not fast during Ramadan—to more conservative practitioners.

The gradual assimilation of the Orang Laut into Malay society was closely tied to their conversion to Islam. As they adopted Islam, Malay customs, and the Malay language, many Orang Laut came to be officially and socially classified as Malay. This process accelerated during the twentieth century, when state-led assimilation policies encouraged conversion, settlement, and relocation. In some cases, religious practice became superficial, shaped as much by access to social benefits and legal recognition as by conviction. Despite this, many communities retained aspects of their maritime identity and ritual worldview beneath outward conformity.

Not all Orang Laut groups followed the same trajectory. While communities such as the Orang Seletar in Malaysia and Singapore and the Duano in Malaysia and Indonesia are today largely Sunni Muslim, other sea-nomadic peoples retained stronger animistic traditions. The Moken or Urak Lawoi of Thailand and Myanmar, for example, continue to practice spirit-centered rituals, including offerings and ceremonies to ensure health, good harvests, and safe voyages. Annual rites such as “feeding the spirits” remain central to their religious life, although even here Islamic influences are sometimes present.

Overall, the religious landscape of the Orang Laut reflects a layered history of seafaring autonomy, spiritual traditions centered on the marine world, and gradual—often externally driven—integration into dominant religious and cultural systems. Their beliefs today represent a complex blend of ancient animism and later Islamic influence, shaped by centuries of contact, migration, and assimilation into settled Malay societies.

Orang Laut Society and Marriage

Among some Riau–Lingga and Billiton Orang Laut groups, headmen exercised more than merely symbolic authority. In many areas, however, leadership structures were shaped by neighboring dominant cultures, and offices were sometimes imposed from outside, resulting in considerable variation in titles and roles. Malay rulers of Johor, and later of Bintan and Lingga, compelled Riau–Lingga sea nomads to become feudal dependents, referring to them as Orang Rayat (“sea subjects”). These rulers persuaded the Orang Laut to render various services, including participation in coastal raiding and piracy against villages and passing boats.[Source: Barbara S. Nowak, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Formal marriage ceremonies are reported only among communities that had converted to Islam. In some groups, such as the Sekah and Kallang, a man was required to own a boat before he could marry. Otherwise, there were few restrictions on spouse selection, and marriage partners could be chosen either from within the same boat community or from outside it.

There are no clear reports of remarriage after widowhood, although White notes the existence of a stepparent kin term, which suggests that such unions may have occurred. Postmarital residence is predominantly patrilocal, with couples typically establishing residence on their own boat after the birth of a child. Notable exceptions include the Orang Sekah and Orang Sama, who practice matrilocal residence, and the Orang Laut, among whom a husband does not usually join his wife’s boat group until after their first child is born. White further suggests that among the Orang Laut, divorce is regarded as morally wrong or “sinful.”

Orang Laut Economic Life

In the past most boat-dwelling Orang Laut groups did not grow food, though White noted sporadic planting of fruit trees. Sedentarized sea nomads, such as the Orang Laut Kappir and those living on King Island, did cultivate fruit trees and subsistence crops. [Source: Barbara S. Nowak, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Although they were otherwise highly skilled marine-oriented peoples, the Orang Laut traditionally relied on relatively simple technologies. Fishing with nets, lines, and traps—common among many non–Orang Laut coastal communities and among sedentarized Orang Laut—was generally absent among fully sea-dwelling Orang Laut groups. More settled and acculturated boat people, such as the Desin Dolaq, later adopted more elaborate fishing techniques learned from neighboring populations.

Traditionally, the Orang Laut worked for traders, washing tin ore or collecting mangrove wood for charcoal. Some groups, including the Orang Sekana and Galang, were involved in piratical activities, often with the support or encouragement of Malay chiefs who exercised nominal political authority over them. Piracy had significant economic, social, and demographic consequences, affecting not only the raiding groups but also other Orang Laut communities that became their targets. Over time, many of these groups were pacified, though elements of trading activity persisted.

In the realm of industrial arts, wood, grasses, lianas, bamboo, and pandanus served as basic raw materials. Men were especially renowned for their boat-building skills, while women were highly regarded for their production of pandanus mats. By contrast, women’s pottery making and men’s blacksmithing largely disappeared following the introduction of inexpensive manufactured trade goods.

Orang Laut Cuisine

Wee Ling Soh of the BBC wrote: The Orang Laut have been assimilated into Malay culture and have lost their language. But descendants of the seafaring nomads are reviving their culture through food...Visits to Asnida Daud's late grand-aunt's flat always promised a mouth-watering spread, with the family sitting cross-legged on the floor and eating with their hands in the customary way. Years after her grand-aunt had been resettled into a one-bedroom flat in Clementi, a residential estate in the south-western part of mainland Singapore that's a far cry from the stilted village on the shores of Pulau Sudong island where she used to live, she continued to make food the only way she knew, evoking a nostalgic longing for the island's white sandy beach and carefree way of life. [Source:Wee Ling Soh, BBC, August 25, 2021]

The highlight of the meal was usually a fiery red asam pedas (sour and spicy fish stew) made with ikan pari (stingray), the perfect accompaniment to plates of fluffy white rice. "It's so spicy your sweat drips onto your rice as you eat, yet you can't stop eating," enthused Asnida. Asnida remembers seeing her late grandmothe crush spices with a batu giling when she was just four. Today the same batu giling sits in her mother's home as a prized family heirloom. She has memories of eating boiled belangkas (horseshoe crab) eggs — creamy with a texture and taste similar to salted egg yolk — and siput ranga, blanched with hot water poured into the shell, on her visits to Pulau Sudong. She also recalls learning the Orang Laut dishes that are perceived to have health benefits. Asnida's aunt, for example, would prepare a nourishing sea cucumber rice porridge to eat after she gave birth; while Firdaus' late great-grandmother, a midwife, used to make a raw sea cucumber salad with buah cermai (Malay gooseberry), asam (tamarind), dried chilli, belacan and fried coconut.

Orang Laut cuisine, which is characterised by fresh seafood obtained using traditional fishing and foraging methods and cooked simply in spices, is now lost in the broader umbrella of Malay food, sometimes even unknown to descendants of the Orang Laut themselves. While flavourful dishes like sotong hitam (squid in squid ink), siput sedut lemak (sea snails in coconut gravy) and asam pedas are easily found at nasi padang (rice with precooked dishes) stalls in Singapore, mainstream Malay food culture tends to not account for variations in the dishes that exist throughout the Malay Archipelago — including those of the Orang Laut — thus leaving their origins unquestioned and stories left untold.

Fourth-generation Orang Laut Firdaus Sani opened Orang Laut Singapore, a home-based food delivery business that doubles as an initiative to share his culture and honour his community's traditional ways of life. "A lot of our food has been lost in time or is not perceived to be unique," he told the BBC. "My quest is to shed light on Orang Laut cuisine, helping it find its place on Singapore's food map. Though we have little access to fishing or foraging today, we recognise the unique food that shapes our cuisine such as ikan buntal (pufferfish) and siput ranga (spider conch), a mollusc that can only be foraged at low tide. We are trying to retain our cuisine by using traditional cooking methods as well as respecting the choice of ingredients in our recipes, how food should be prepared for cooking and why some seafood should be cooked a certain way."

For example, in Firdaus' family, ikan buntal is cooked "kerabu" style, the boiled fish mixed with water spinach and lemongrass before stir-frying in a thick paste of dried chilli, garlic, belacan (shrimp paste), onion and black peppercorn. Preparation takes about a day, starting with skinning the fish, segmenting the edible parts and removing the poison. Every part can be consumed except the skin. The intestines are cleaned thoroughly then braided to prevent them from breaking during the hours-long boiling process. Once boiled, the bones are removed and parts like innards and gills are sliced thinly for cooking. While Singapore's stringent food safety standards mean it is near impossible for Firdaus to sell locally caught pufferfish, he offers other traditional dishes such as sotong hitam and gulai nenas (pineapple in prawn broth) cooked by his mother and aunt.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “The forgotten first people of Singapore” by Wee Ling Soh, BBC BBC.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026