ETHNICITY IN MALAYSIA

Malaysia is a mix of Malay Muslims, Chinese Buddhists and Christains, Indian Hindus and indigenous tribes. These groups have tended to remain someone separate and apart from the others rather than assimilate as different groups have done in the United States. Malaysia has been described as an ethnic salad bowl rather than a melting pot.

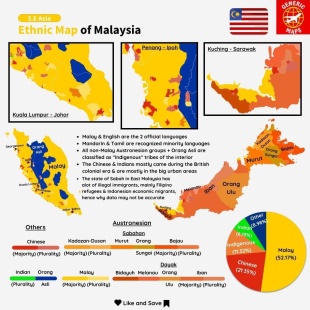

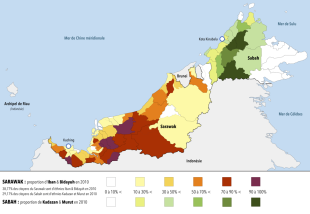

People of Austronesian origin make up the majority of the population, and are known as the Bumiputras. This includes Malays and Orang Asli (indigenous people of Malaysia, which comprise 0.7 percent of Malaysia’s total population. There are also large numbers of Chinese and Indians. [Source: Wikipedia]

Since race riots in 1969, Malays have been especially privileged in Malaysia – top government positions are reserved for them, and they receive cheaper housing, priority in government jobs as well as business licenses. However, since the riot, racial stability has prevailed, if not full harmony, and mixed marriages are on the rise.

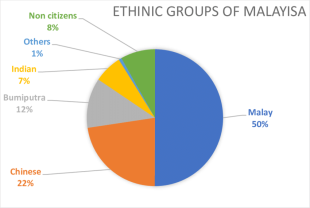

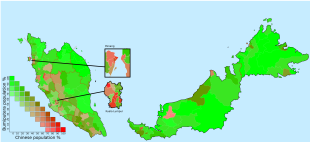

Ethnic groups in Malaysia (2020 census): 1) Bumiputeras (69.4 percent); 2) Chinese (23.2 percent); 3) Indians (6.70 percent); 4) Others (0.70 percent). In the 2010 census, 68.8 percent of the population were considered bumiputera, 23.2 percent Malaysian Chinese, and 7 percent Malaysian Indian. According to the 2000 census, 50.2 percent of the population was Malay, 24.5 percent Chinese, 11 percent indigenous, 7.2 percent Indian, and 1.2 percent members of other ethnic groups. Non-Malaysian citizens make up the remaining 5.9 percent.

These groups often can be divided by language, tribe, and other categories. Since independence, a common national identity has solidified, but ethnic divisions remain apparent in many aspects of daily life. Malays and indigenous groups often refer to themselves as “bumiputra” (“sons of the soil”), and ethnicity is associated with differences in politics, residence, socioeconomic position, and daily customs. The government has affirmative-action policies designed to promote social harmony, but critics claim such policies unfairly favor ethnic Malays over other groups. Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)

Ian Buruma wrote in The New Yorker, “The country’s population is more than half Malay, defined by ethnicity and the Muslim faith, but large numbers of Chinese (now about a quarter of the population) and Indians (seven percent) arrived in the 19th century, when the British imported coolies from China and plantation workers from India. Tensions arising from this melange “” and, in particular, the fear held by Malays that they will always be bested by these minorities “” have gripped Malaysian politics since the country achieved independence from the British, in 1957. In recent years, the situation has been further complicated by a surge in Islamic fervour among many Malays. [Source: Ian Buruma, The New Yorker, May 19, 2009 ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

CHINESE IN MALAYSIA: HISTORY, GROUPS, BUSINESS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

INDIANS IN MALAYSIA: HISTORY, WORK, DISCRIMINATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS OF MALAYSIA): LIFE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

SENOI: HISTORY, GROUPS, DREAM THEORY factsanddetails.com

TEMIAR: HISTORY, SOCIETY AND RICH RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJUA SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Ethnic Harmony in Malaysia

Malaysia's diverse ethnic groups have traditionally gotten along in a way that some say countries in the Balkans and the Middle East should try to emulate. The Malaysian constitution prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, descent, sex and place of birth.

The Malaysian government has worked hard to promote ethnic harmony: running television spots with representatives of every Malaysia ethnic group smiling and singing "All together, Mah-lay-see-ah, you can be a star!" During Muslim holidays, Chinese and Indian business post signs honoring the events and televisions commercial show non-Muslims wishing Muslims god fortune. During Chinese and Indian holidays, Muslim Malay extend the same respect and cordiality.

"More than ever in my life were are feeling Malaysian now," a turbaned Sihk driver told T.R. Reid in a National Geographic article in the 1990s. "When I was in school here, we felt we were Indians. Always we're were Indians, who happened to be living in a country with a lot of Malays and Chinese. But my children! Always the are saying, 'We are Malaysians.'"

Explaining the reason for Malaysia's racial tolerance, political scientist Patrick Mayerchak told National Geographic, "partly, it's that everybody was frightened by the riots” in 1969 that left as many as 200 dead. "It's also a function of the economy, because life got better for everyone. The New Economic Policy was another key piece."

Lack of Ethnic Harmony in Malaysia

In the mid 2000s prime minister, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, warned that race relations had become "brittle." "We must eliminate all negative feelings toward each other," he was quoted in the Star newspaper as saying. Around that time Thomas Fuller wrote in York Times: “A nationally televised meeting of the Malay governing party in November 2006 shocked many Malaysians for its communalism, including comments by one delegate who said the party was willing to "risk lives and bathe in blood in defense of race and religion." He was subsequently reprimanded, but only after an outcry from Chinese and Indians. Early in November, the chief minister of the southern state of Johor, Ghani Othman, went as far as to question whether a Malaysian nation actually existed, describing it as a "rojak," or mish-mash of races, that was diluting the Malay identity. [Source: Thomas Fuller, New York Times, December 13, 2006]

In April 2008, following a bitter general election in which the ruling coalition lost a significant number of seats—partly due to dissatisfaction among Chinese and Indian voters—Malaysia’s king used the opening of the new Parliament to call for racial harmony. Speaking to a joint sitting of both houses, Sultan Mizan Zainal Abidin, the country’s constitutional monarch, warned that political stability and racial unity were central to Malaysia’s success. He urged lawmakers from all parties to take responsibility for uniting the nation and resisting efforts to divide its people. .[Source: Associated Press, February 15, 2008; August 3 2009]

At the same time, commentators noted growing resentment among minority communities toward Malay political dominance and what many perceived as the gradual expansion of Islamic influence in public life. Writing in the Financial Times, John Burton observed that urbanization had intensified competition for jobs and sharpened ethnic identities, reducing everyday interaction between communities. Jawhar Hassan, head of Kuala Lumpur’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies, said these pressures had made ethnic differences more pronounced. [Source: John Burton, Financial Times, January 9, 2008]

Legal disputes over religious conversion further deepened these divisions. Civil courts ruled that cases involving Muslims seeking to change their religion fell exclusively under the authority of Islamic sharia courts, which generally oppose apostasy. Critics argued that these rulings undermined religious freedom and contributed to the formation of Hindu activist groups, including the organization that later led mass Indian protests. Sixty-two-year-old ethnic Indian S.K. Lingam, a taxi driver, told Reuters in 2007 that despite Malaysia's races had drifted apart in recent years. "Two decades ago, when I used to be in the merchant navy, we used to gather together on weekends for BBQs and parties. It didn't matter what religion we were ... Over the last few years, people don't seem to get together on weekends too much." [Source: Reuters August 31, 2007]

Muhibbah

Charukesi Ramadurai of the BBC writes: What keeps Malaysians together is not just a shared love for their country, but the spirit of muhibbah. In the Arabic language, where it comes from, muhibbah (also muhibah) means love or goodwill. In Malaysia, it is that and much more. According to Dr Kamar Oniah Kamaruzaman, scholar and professor of religious studies, muhibbah in Malaysia is about togetherness, or “understanding, caring, empathy and kinship”. [Source: Charukesi Ramadurai, BBC, March 10, 2021]

When Malaysia gained independence from Britain in 1957, the leaders decided to adopt muhibbah as the unifying spirit of this new country to ensure there would be no tension between the various ethnic and religious groups. For example, while the country is officially an Islamic state, everyone has the right to follow their religious beliefs as well as speak their own languages. Even now, I see local newspaper articles in which politicians call upon this word as a reminder to continue with peaceful coexistence.

“Our mamak stalls are the perfect example of muhibbah,” said Salwah Shukor, a Kuala Lumpur resident, explaining how practically everyone eats at the fresh food restaurants run by Muslims from South India that serve cheap halal food to satisfy diverse palates. There is an easy camaraderie among mamak customers, whether their meal is a local Malay dish tossed with Chinese sauces, or a sizzling-hot South Indian dosa (called thosai here) with coconut chutney on the side.

Having grown up with Indian family friends and Chinese classmates at school, Shukor insists that it is impossible to stay isolated within one’s own community in Malaysia. “The three communities have their own strengths and weaknesses, we have learned to use them to our collective advantage and we are all better as the sum of all parts,” she said.

Indeed, Kamaruzaman insists that muhibbah does not mean tolerance: “To just tolerate is not really a nice feeling, it is condescending. Muhibbah is the opposite of tolerance, it means acceptance.” She also cites mamaks as an example, saying, “You can find nasi lemakthere (a Malay dish of fried rice), as well as roti canai (a flatbread and curry dish of Indian origin) and cendol (a South-East Asian dessert of coconut milk, jelly noodles and shaved ice) — nobody questions where this or that dish comes from, India or China? They are all Malay cuisine now.”

How Muhibbah Is Expressed

Writer and academic Dipika Mukherjee, who grew up in Malaysia and currently lives in the US, told the BBC that her experience has been all about embracing her various identities. “I could wear shorts and walk to a mamak for breakfast, and then travel on the bus wearing a sari to visit my Indian family — in either case, nobody would look at me strangely like I am in costume. Here in the US, everyone has to become homogenised into a single white identity, wearing and eating what everyone else does, but not so in Malaysia.” [Source: Charukesi Ramadurai, BBC, March 10, 2021]

Ramadurai writes: Malaysia’s muhibbah also means that the country’s festival calendar spreads through the year, beginning with the Chinese Lunar New Year celebrations right at the beginning; Hari Raya or Ramadan sometime in the middle; and Deepavali (another name for Diwali, the festival of lights) in the later months. And as I discovered to my pleasant surprise, there is still room for Christmas with main streets and shopping malls alike decked up with sparkly decorations and even fake snow.

Another manifestation of this multiculturalism is the “open house” that Malaysians keep during festivals, where food and drinks (non-alcoholic, in the case of Muslim homes) are laid out every evening to welcome friends, relatives and even strangers. “It used to be only Malays celebrating Hari Raya with an open house, but many Indians now do it at Deepavali, and occasionally even the Chinese for their new year,” Shukor said.

Impact of Taleban Lite of Racial Relations in Malaysia

Nick Meo wrote in The Times, “Some fear that assertive Islam threatens to upset the delicate balance between the 60 percent Malay Muslim majority and the nonMuslim ethnic Chinese and Indian minorities, which have managed to coexist, sometimes uneasily, since the troubled birth of the country in 1957, at a time of civil war and ethnic tension. At the time many feared that the new nation was doomed to failure. It has instead built a strong economy and an imperfect democracy, dominated for 50 years by the United Malays National Organisation, which has survived without the coups or upheavals that have plagued her neighbours. [Source: Nick Meo, The Times, August 18, 2007 +]

Ronnie Liu, of the Democratic Action Party, said: “Socialising between Malays and the other ethnic groups is much rarer than it used to be. You go into coffee shops and restaurants now and they no longer cater to an ethnic mix of customers. It wasn’t like that before.” Some nonMuslim Chinese and Indians feel increasingly treated like second-class citizens. They complain, usually privately, that Islamic religious schools are much better funded than theirs and that a system of affirmative action favours Malays when it comes to university places. +

“Minority religions are particularly worried about a series of apostasy rulings. Chinese or Indians who want to marry a Malay must convert to Islam, causing great problems if they divorce or are widowed and want to return to the religion of their birth. In a notorious case this year a Malay woman called Lina Joy attempted to have Malaysia’s courts recognise her conversion to Christianity, but failed and was hounded and fled into hiding. Some hardliners have even called for the execution of apostates.”

Ethnicity and Politics in Malaysia

Malaysian politics have traditionally been divided along racial lines. After serious riot between Muslims and Chinese during the election in 1969 an effort was made to make sure that elections do not take a racial nature. Muslims (most of them Malays) make up 60 percent of Malaysia's population and form the bulk of voters for the United Malays National Organization. The party dominates the National Front coalition, which includes Chinese- and Indian-based parties in a power-sharing arrangement that has ensured racial peace in this multiethnic country.

Ethnic Malays and Muslims, who comprise some 60 percent of Malaysia’s 27 million people, control political power. Many ethnic Chinese and Indians, who form the two main minority communities, complain their grievances are ignored, especially regarding an affirmative action program that gives privileges to Malays in business, jobs and education.

Although Malays make up the majority of the population they can be divided along various lines such moderate Muslims versus more Islamic Muslims. The Chinese are a minority, but a sizable one at 25 percent of the population. They often play the role of swing voters.

According to Reuters: “Malaysia is dominated politically by ethnic Malays, who are Muslims and see themselves as the natural rulers and indigenous race. But they make up only a slender majority — ethnic Chinese and Indians account for almost 40 percent of the population. The social melting pot, partly a legacy of colonial times when former ruler Britain imported Chinese and Indian labor to work mines and plantations, has left Malaysia with a major challenge to keep the peace between the races. With conservative Islam on the rise in Malaysia, non-Muslims have begun to complain that their constitutional right to freedom of worship and to secular government are being compromised.The Malay deputy premier recently called Malaysia an Islamic state, angering non-Muslims. Increasingly, leaders of the multi-racial government are urging Malaysians to heed the lessons of 1969, when racial tensions burst into deadly riots. [Source: Reuters August 31, 2007]

New Economic Policy: Malaysia’s Affirmative Action Plan

The New Economic Policy (NEP) is an affirmative action plan implemented in the 1970s in response to the ethic riots of 1969 to counter the economic dominance of the country's ethnic Chinese minority and improve economic position of naive Malays. The policy has helped indigenous Bumiputras (native Malays, literally "sons of the soil") improve their positions by giving them preferential treatment in education, business and government, and setting quotas that limited the number of Chinese and Indians in universities and public jobs. Malays were given preferences in housing, bank loans, business contracts and government licenses.

The policy is backed by a special clause in the Constitution guaranteeing preferential treatment for Malays. It imposes a 30-percent bumiputra equity quota for publicly listed companies and gives bumiputras discounts on such things as houses and cars. Money is provided by banks and investment firms to Malays and indigenous people to start businesses. Businesses are required to have a bumiputra partner, who would hold at least a 30 percent equity stake.

The policy was introduced under Prime Minister Abdul Razak, the father of disgraced Prime Minister Najib Razak. It emerged in the aftermath of the 1969 racial riots, which were driven in part by Malay perceptions that ethnic Chinese dominated the economy. To address these imbalances, Razak designed an affirmative-action program aimed at raising the share of national wealth held by Malays and other indigenous groups to at least 30 percent. The policy provided Malays with preferential access to housing, university admissions, government contracts, and shares in publicly listed companies. [Source: Shamim Adam, Bloomberg, September 09, 2010]

Racial Mixing and a Lack of It at Malaysian Universities

At most Malaysian universities, Malays hang out with Malays, Chinese hang out with Chinese and Indians hang out with Indians. For the most part groups are mixed in the classroom but not outside it. For food, Malays flock to the counter offering spicy rice and curry, Chinese congregate at noodles stalls and Indians eat mutton stew. Sports too have traditionally been segregated, with Malays preferring soccer and Chinese playing badminton or relaxing at a swimming pool, a place usually off limits to Muslim women.

In an efforts to change that pattern, the University of Science in Penang has encouraged student to share rooms with a roommates not of their ethnic group. Sometimes the Chinese complain about being woken up by their Malay roommates at 5:00am when they wake up for morning prayers.

School textbooks teach tolerance. They were introduced to avoid violence like the riots in 1969. In July 2004, the government announced that university students would be required to pass a course on understanding other ethnic groups before they would be allowed to graduate.

For some time a quota system has been in place to make sure that certain groups—particularly Malays—are give a certain number of university positions even though other groups—particularly Chinese—may have higher entrance scores and be better qualified. There has been some discussion of getting rid of the system because of its inherent unfairness.

Malaysia Versus Indonesia on Race Policy

Thomas Fuller wrote in York Times: “Indonesia and Malaysia have much in common: language; a border that slices across Borneo; overlapping ethnic groups. But the two countries are moving in opposite directions on the fundamental question of what it means to be a "native." With a new citizenship law passed this year, Indonesia has redefined "indigenous" to include its ethnic Chinese population — a radical shift from centuries of policies, both during colonial times and after independence in the 1940s, that distinguished between natives and Indonesia's Chinese, Indians and Arabs. [Source: Thomas Fuller, New York Times, December 13, 2006]

Malaysia, meanwhile, is sticking to its longstanding policy that Malay Muslims, the largest ethnic group in the country, are "bumiputras," or sons of the soil, who have special rights above and beyond those of the country's Chinese and Indian minorities. Maintaining this controversial policy has led to what one commentator calls a retribalization of Malaysian politics, with rising assertiveness on the part of the country's Malay Muslims.

“Both Indonesia and Malaysia have suffered race riots in recent decades. Indonesia's were much bloodier and more far-flung. Yet today, ethnic tensions are more likely to make headlines in Malaysia than Indonesia. Malaysia's Chinese community was angered by the demolition of a Taoist temple in Penang. Both Muslims and non-Muslims are upset about a series of disputes over whether Shariah or secular law should take precedence....Paradoxically, some in Malaysia, which has long been wealthier and more politically stable, are looking admiringly at developments in Indonesia. Azly Rahman, a Malay commentator on the widely read Web site Malaysiakini, said poor Indians and Chinese are neglected under the current system. "A new bumiputra should be created," he said. "Being a Malaysian means forgetting about the status of our fathers. We need affirmative action for all races."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Common

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026