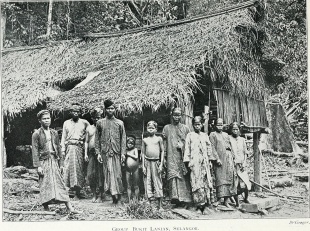

ORANG ASLI

The Orang Asli are a diverse indigenous population and national minority in Malaysia. They are the oldest inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia. As of 2017, they accounted for 0.7 percent of Peninsular Malaysia's population. In many cases these people were in present-day Malaysia long before the Malays but became subordinate to the Malays and in some cases were enslaved by them after Malays took control of the peninsula.

The term Orang Asli (Malay for “original people” or aboriginals) describes tribal or recently tribal people that live in peninsular Malaysia. ‘Orang Asli’ are divided into three main tribal groups: Negrito (Semang), Senoi and Proto-Malay. The Negrito usually live in the north, the Senoi in the middle and the Proto-Malay in the south. Each group or sub-group has its own language and culture. Separating the Orang-Asli into three official “groups” is a bit misleading. There are, in fact, 18 ethnic group are pressed into one collective term, and their cultural appearance is quite diverse. Some are fishermen, some farmers and some are semi-nomadic.

The government agency in charge of handling affairs with these groups is the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (Jabatan Hal Ehwal Orang Asli, or JOA). The aboriginal People’s Act of 1954, revised in 1974, gives police the right to control who enters Orang Asli villages and gives the Malaysia government the power to allocated Orang Asli land. The JOA has brought schools. Health care and development to tribal areas but in many ways government actions are motivated by a belief that the Orang Asli are primitive and need to be civilized.

A very detailed summary of the political and social state of the Orang Asli today has been written by Colin Nicholas, Center for Orang Asli Concerns. The traditional dances of the Peninsular Malaysia's Orang Asli are strongly rooted in their spiritual beliefs. Dances are commonly used by shaman as rituals to communicate with the spirit world. Such dances include Genggulang of the Mahmeri tribe, Berjerom of the Jah-Hut tribe and the Sewang of the Semai and Temiar tribes.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEMANG (NEGRITOS OF MALAYSIA): LIFE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

SENOI: HISTORY, GROUPS, DREAM THEORY factsanddetails.com

TEMIAR: HISTORY, SOCIETY AND RICH RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MALAYSIA: HARMONY, DISHARMONY, GOVERNMENT POLICIES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

Early Indigenous People in Malaysia

Location of Orang Asli groups,

and the spread and assimilation of settlers

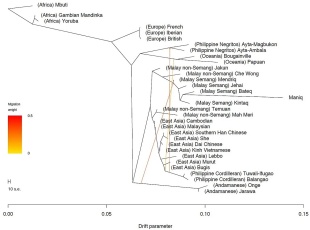

on the Malay Peninsula The indigenous groups on the peninsula can be divided into three ethnicities, the Negritos, the Senois, and the proto-Malays. The first inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula were most probably Negritos. These Mesolithic hunters were probably the ancestors of the Semang, an ethnic Negrito group who have a long history in the Malay Peninsula. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population.

The Proto Malays have a more diverse origin, and were settled in Malaysia by 1000BC. Although they show some connections with other inhabitants in Maritime Southeast Asia, some also have an ancestry in Indochina around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 years ago. Anthropologists support the notion that the Proto-Malays originated from what is today Yunnan, China. This was followed by an early-Holocene dispersal through the Malay Peninsula into the Malay Archipelago. Around 300 BC, they were pushed inland by the Deutero-Malays, an Iron Age or Bronze Age people descended partly from the Chams of Cambodia and Vietnam. The first group in the peninsula to use metal tools, the Deutero-Malays were the direct ancestors of today's Malaysian Malays, and brought with them advanced farming techniques. The Malays remained politically fragmented throughout the Malay archipelago, although a common culture and social structure was shared.

Anthropologists traced a group of newcomers Proto Malay seafarers who migrated from Yunnan to Malaysia. Negrito and other Aborigines were forced by late comers into the hills. In this period, people learned to dress, to cook, to hunt with advanced stone weapons. Communication techniques also improved.

Archaeological finds from the Lenggong valley in Perak. Dating to 10,000-5,000 years ago- Neolithic (New Stone Age), show that people were making stone tools and using jewellery. In the Bronze Age, 2,500 years ago, more people arrived, including new tribes and seafarers. The Malay Peninsula became the crossroads in maritime trades of the ancient age. Seafarers who came to Malaysia's shores included Indians, Egyptians, peoples of the Middle East, Javanese and Chinese. Ptolemy named the Malay Peninsula the Golden Chersonese.

Early History and Enslavement of the Orang Asli

The expansion of the regional slave trade had a profound impact on the Orang Asli. From as early as 724 CE, during contact with the Srivijaya Empire, Negrito groups were enslaved, with some exploitation continuing into modern times. Because Islamic law forbade enslaving Muslims, slave raiders targeted non-Muslim Orang Asli, reinforcing the Malay use of the term sakai as “slave.” By the sixteenth century, Malacca had become a major slave-trading center. In the 18th and 19th centuries,

Orang Asli groups were victims of organized raids—particularly by the Aceh Sultanate, Minangkabau, and Batak groups. These devastated Orang Asli communities. Villages were attacked, adult men killed, and women and children captured and sold into slavery, where they served as laborers, servants, or concubines.

Many of the slave traders were Malays from Sumatra. Sometimes, they provoked or forced Orang Asli leaders to abduct people from another Orang Asli group. The Malays then handed these people over to them in an attempt to protect their own wives from captivity. Some Orang Asli became willing slaves, forming the labor force in cities and in the households of chiefs and sultans. Others were sold in slave markets to traders who transported them to other lands, including Java.

Relations between Malays and Orang Asli were not always violent, however, and some groups coexisted peacefully. Over time, increased contact led many indigenous communities to be absorbed into Malay society through processes of cultural and linguistic assimilation, contributing to the ancestry of modern Malays. To avoid enslavement and outside influence, other Orang Asli groups retreated deeper into the interior, where geographic isolation and nomadic lifestyles allowed them to preserve distinct languages, customs, and beliefs. While some inland groups maintained limited trade with Malays, a minority resisted assimilation altogether, including communities that refused conversion to Islam.

Later History of the Orang Asli

The British colonial rulers established laws to protect the Orang Asli. In 1954, the Department of Aboriginal Affairs was established in part to prevent the Orang Asli from joining the Communist insurgency. As a rule many Orang Asli have not got on well with the Malays. Many Orang Asli groups were moved onto “relocation settlements” in the 1970s in part so the government could carry out anti-insurgency operations against Communist insurgents.

The Malayan Emergency of the 1950s in British Malaya accelerated the state's penetration of the interior. In an attempt to deprive the Malayan Communist Party of support from the Orang Asli indigenous people, the British forcibly relocated them to special camps under the protection of the army and police. They lived in the camps for two years, after which they were allowed to return to the jungle. This event was a severe blow, as hundreds of people died from various diseases in the camps.

Since the 1980s, Orang Asli areas have been invaded by individuals, corporations, and state governments. Logging and replacing jungles with rubber and oil palm plantations have become widespread, reaching their greatest scale in the 1990s.

In 1997, a campaign was launched to covert the Orang Asli to Islam. Robert K. Dentan, an anthropologist at the State University of New York in Buffalo told the New York Times: “Take away their land, their trees, the Orang Asli will no longer be able to support themselves or maintain distinctive culture. They will become either dependents of the state or a kind of landless proletariat, low-wage laborers at the very bottom of society.”

Orang Asli Population and Demography

The Orang Asli population is estimated at about 148,000 people. The largest subgroup is the Senoi, who make up roughly 54 percent of the total population, followed by the Proto-Malays at 43 percent, and the Semang, who account for about 3 percent. In Thailand, there are approximately 600 Orang Asli, including Mani people with Thai citizenship and about 300 others living in the deep south. Overall, the Orang Asli population has been growing steadily for decades, with an average annual growth rate of about 4 percent between 1947 and 1997, largely attributed to improvements in living conditions, healthcare, and general quality of life. [Source: Wikipedia]

Historical census data show a long-term increase in population. Numbers rose from 9,624 in 1891 to 17,259 in 1901, reaching 30,065 by 1911. Growth slowed slightly in the interwar years but resumed after World War II, increasing from 34,737 in 1947 to 41,360 in 1957, and then accelerating to 53,379 in 1970, 65,992 in 1980, and 98,494 in 1991. By 2000, the population had grown to 132,786, and by 2010 it reached approximately 160,993.

In terms of geographic distribution, more than half of the Orang Asli live in the states of Pahang and Perak, which together account for over 70 percent of the population. In 2010, Pahang had 63,174 Orang Asli (39.2 percent), while Perak had 51,585 (32.0 percent). Smaller but significant populations are found in Kelantan, Selangor, Johor, and Negeri Sembilan. Much smaller numbers live in Melaka, Terengganu, Kedah, and the federal territory of Kuala Lumpur.

Very small Orang Asli communities are recorded in Penang and Perlis, where they are not officially considered indigenous. Their presence in these states reflects increasing mobility, as some Orang Asli migrate to industrial and urban areas in search of employment opportunities.

Orang Asli Languages

Linguistically, the Orang Asli fall into two broad groups, speaking languages from either the Austroasiatic or the Austronesian language families. [Source: Wikipedia]

The northern Orang Asli—mainly the Senoi and Semang—speak Aslian languages, a distinct branch of the Austroasiatic family. On linguistic grounds, these groups have historical links with indigenous peoples of mainland Southeast Asia, particularly in Myanmar, Thailand, and Indochina. The Aslian languages are further divided into several subgroups: Jahaic (Northern Aslian), Senoic, Semelaic (Southern Aslian), and the distinct Jah Hut language. The Jahaic subgroup includes languages such as Cheq Wong, Jahai, Bateq, Kensiu, Mintil, Kintaq, and Mendriq. The Lanoh, Temiar, and Semai languages belong to the Senoic subgroup, while Semelai, Semoq Beri, Temoq, and Besisi (spoken by the Mah Meri) form the Semelaic subgroup.

The second linguistic group consists of Orang Asli who speak Aboriginal Malay languages, which are closely related to standard Malay and belong to the Austronesian language family. These include languages spoken by groups such as the Jakun and Temuan. An exception within this broader category are the Semelai and Temoq, who, despite often being grouped with Aboriginal Malays, speak Austroasiatic rather than Austronesian languages.

Semang

The Semang are a Negrito group of hunter-gatherers and shifting cultivators that live in the lowland rain forests in northern Malaysia and southern Thailand. There are only about 2,000 to 5,000 of them depending on the source and they are divided into ten groups whose numbers range from about 100 to almost 1,000. Most Semang languages are in the Mon-Khmer group or the Aslian Branch of the Austroasiatic group of languages. Most also speak some Malay and there are many Malay loan words in Semang languages. [Source: Kirk Endicott, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The term “Semang” was a nineteenth-century label for small, dark-skinned, curly-haired forest peoples of the Malay Peninsula, sometimes subdivided as “Pangan” in the east. Although the idea that they constitute a distinct race is now rejected, these groups share enough cultural traits to be treated as a single category. Outsiders have used names such as “Sakai,” “Orang Asli,” and the Thai “Ngò’ Pa,” while the peoples themselves use names like “Meni’” and “Batèk,” meaning “human beings (of our kind).” ~

The population of Semang has remained at about 2,000 through the 20th century, but individual groups have increased or decreased as conditions changed. Semang generally live in the lowlands and foothills in primary and secondary tropical rain forest of Perak, Pahang, Kelantan and Kedah of peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand between 3°55 and 7°30 N and between 99°50 and 102°45 E. Only the Jahai group inhabit higher elevations. ~

See Separate Article: SEMANG (NEGRITOS) factsanddetails.com

Senoi and Temiar

The Senoi are the largest Orang Asli subgroup, making up about 54 percent of the total Orang Asli population. They comprise six tribes—Temiar, Semai, Semaq Beri, Jah Hut, Mah Meri, and Cheq Wong—who live mainly in the central and northern regions of the Malay Peninsula. Their villages are widely scattered across the states of Perak, Kelantan, and Pahang, including along the slopes of the Titiwangsa Mountains. In physical appearance, the Senoi generally differ from other indigenous groups by being taller, having lighter skin, and wavy hair. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Senoi are a group of slash-and-burn farmers that live in the rain-forested mountains and foothills of the Main mountains range which bisects the Malaya peninsula, primarily in northeast Pahang and southeast Perak. There are about 20,000 of them. Their language is classified as members of the Aslian Branch of the Austroasiatic group of languages. Most also speak some Malay and there are many Malay loan words in Senoi languages. Many have never traveled further than a few kilometers from the place they were born. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population.

See Separate Article: SENOI factsanddetails.com

The Temiar are a Senoic group indigenous to the Malay peninsula and one of the largest of the nineteen Orang Asli groups of Malaysia. Many live on the fringes of the rainforest, while a small number have been urbanised. The Temiar are traditionally animists, giving great significance to nature, dreams and spiritual healing. Most Temiar are slash-and-burn farmers that live in the rain-forested mountains and foothills in a 5000 square kilometer area in the interior parts of Perak, Pahang and Kelantan states in peninsular Malaysia. There are widely dispersed. Their language is classified in the Aslian Branch of the Austroasiatic group of languages. Most also speak some Malay and there are many Malay loan words in Temiar languages. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

See Separate Article: TEMIAR factsanddetails.com

Semai

The Semai are a semisedentary people living in the rainforest in center of the Malay Peninsula. They speak Semai, a Mon-Khmer language. The Semai belong to the Senoi ethnic group. Regarded as a Senoi subgroup, the Semai are often regarded as descendants of an ancient and once widespread population of Southeast Asia. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Semai population in the late 2020s was 65,000. According to Keene State College’s Orang Asli Archive, there were 26,627 Semai living on the Malay Peninsula in 1991, a number that increased afterwards with improvements in nutrition, sanitation, and healthcare. These figures, however, do not include people of Semai or mixed ancestry who have largely assimilated into other societies, often leaving their ancestral lands to pursue education and employment, especially in urban centers. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Semai are frequently cited among the few societies reported to have never engaged in warfare, alongside groups such as the Andaman Islanders of India and the Yahgan of Patagonia. A 1995 genetic study by researchers from the National University of Singapore found a close relationship between the Semai and the Khmer of Cambodia, consistent with the Semai language’s place in the Mon–Khmer branch. Genetically, the Semai also appear to be more closely related to the Javanese than to neighboring Malay populations.

Like other Orang Asli groups, the Semai were gradually displaced into upland and mountainous regions by later, more technologically dominant peoples. They have no formal government or police force, and social order is maintained largely through public opinion. As the Semai themselves put it, “There is no authority here but embarrassment.” While articulate and respected individuals may influence communal decisions, the society lacks formal leaders.

Semai Society and Religion

The Semai are particularly noted for their strong commitment to nonviolence. Along with other hunter-gatherer societies such as the Bushmen of the Kalahari, they are often described as among the most nonviolent peoples in the world. Even childhood conflicts are handled collectively: when a child strikes another, the community convenes a “parliament of children,” where all the children sit together to discuss what happened, why it occurred, and how to prevent it in the future. In this way, children learn that conflict affects the entire community, not just those directly involved. [Source: Wikipedia]

Disputes among adults are settled through a becharaa, a public assembly held at the headman’s house. These gatherings can last several days and involve detailed discussion of the causes and motives of the dispute, as well as its resolution, with participation from both the disputants and the wider community. The process usually ends with a warning from the headman that repeated misconduct could endanger the group. Reflecting this outlook, the Semai say that “there are more reasons to fear a dispute than a tiger.”

According to Joshua Project most Semai practice traditional religions. Five to 10 percent are Christians, with two to five percent or their population being Protestant Evangelicals. Semai religious life is rooted in animism. Their beliefs include a thunder deity known as Enku, and a small eyeless snake regarded as “Thunder’s headband.” Thunder is also associated with the Na-ga, powerful subterranean dragon-like beings believed to ravage villages during violent storms and to be linked with rainbows. One important ritual, chuntah, is performed to drive away malevolent spirits. It takes place during a storm, when a man collects rainwater in a bamboo container and then mixes it with his own blood before the ritual is completed.

The Semai also classify the natural world in distinctive ways. Animals are grouped as cheb, which have feathers and fly; ka’, which have scales or moist skin and live in or near water; and menhar, which live on land or in trees—a category that also includes fungi. Dietary rules often prohibit animals that seem to cross these categories. Snakes, for example, are usually not eaten because they move like legged land animals yet lack legs, a combination considered unnatural.

Semai Life and Culture

The Semai are horticulturalists who have a gift economy. They used to wear reed loincloths. Semai have a strong craving for meat. When they say “I haven’t eaten for days,” it usually implies they haven’t eaten meat for days. In matters of space and ownership, the Semai make little distinction between public and private realms, and the Western notion of privacy is largely absent. This outlook is also found among rural Malays, many of whom descend from intermarriage with Semai and other Orang Asli groups and have retained aspects of Semai knowledge, values, and nonviolent traditions alongside later religious influences. [Source: Wikipedia]

Semai villages consist mainly of houses built from wood and bamboo, with woven walls and palm-leaf thatched roofs. Homes typically lack separate bedrooms, especially for children, who sleep together in the main hall. Privacy is created only by simple curtains—often wooden-beaded—for the parents’ sleeping area. Similar practices are found among coastal Malays, who use seashell curtains, and among deutero-Malays, who use batik cloth. There are no locks or barriers; instead, a closed curtain signals that entry is not permitted, while drawing it aside indicates welcome. Entering without permission is considered a serious breach, believed to invite natural or supernatural consequences.

Semai children are neither punished nor compelled to act against their will. If a parent makes a request and a child refuses, the matter usually ends there. When behavioral guidance is needed, parents rely instead on invoking natural dangers—such as strangers, thunderstorms, or lightning—and on moral teachings. Stories about forest spirits and sprites (mambang) convey a belief in retribution for harmful or disrespectful behavior, reinforcing a concept similar to karma. Children are also taught to be wary of their own aggressive impulses. Central to Semai upbringing is the value of mengalah, or giving way to others, which children learn from an early age as a means of preserving harmony and peace within the community.

Children’s games reflect this emphasis on cooperation rather than competition. Physical play is encouraged, but without winners or losers, often with the aim of tiring the body in preparation for sleep and dreaming. In one game, children swing sticks at one another but always stop short, ensuring no one is actually hit. Even modern sports are adapted to this ethos: badminton, for example, is played without nets or scoring, and the shuttlecock is hit gently so it can be easily returned. The focus is on movement and shared activity rather than rivalry.

Proto-Malays

Proto-Malays, also known as Aboriginal Malays, form the second-largest Orang Asli group, accounting for about 43 percent of the total population. They comprise seven distinct tribes: Jakun, Temuan, Temoq, Semelai, Kuala, Kanaq, and Seletar. During the colonial period, these groups were often inaccurately lumped together under the name Jakun. Today, they live mainly in the southern half of the Malay Peninsula, particularly in Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Melaka, Pahang, and Johor, with settlements commonly located along upper river courses and in coastal areas not taken over by Malays. [Source: Wikipedia]

In appearance, customs, culture, and language, Aboriginal Malays closely resemble Malaysian Malays. They generally have darker skin, straight hair, and an epicanthic fold. Most are now settled communities, with livelihoods centered on agriculture, fishing in riverine or coastal areas, and wage employment. Some are also engaged in business or professional occupations.

Despite the umbrella term, the tribes themselves are quite diverse. The Temuan, for instance, have a long-established agricultural tradition, while the Orang Kuala and Orang Seletar are primarily maritime peoples involved in fishing and seafood-related activities. The Semelai and Temoq stand apart linguistically, as their languages differ significantly from those of other Aboriginal Malay groups.

Historically, these tribes were organized as separate communities that experienced limited outside influence. They are often distinguished from Malaysian Malays by religion, as most are not Muslim, although some groups—such as the Orang Kuala—converted to Islam before Malaysia’s independence.

Differences among Aboriginal Malays are also reflected in theories about their origins. A commonly held but scientifically unproven view in Malaysia and Indonesia divides Austronesian peoples into Proto-Malays and Deutero-Malays. According to this idea, Proto-Malays settled the Sunda archipelago around 2,500 years ago, while Deutero-Malays arrived later and intermingled with earlier inhabitants and various other populations, contributing to the emergence of modern Malay society. Although lacking firm scientific support, this framework continues to influence popular perceptions of indigenous groups.

Some Aboriginal Malay tribes, notably the Orang Kanaq and Orang Kuala, are sometimes regarded as later migrants rather than long-established indigenous peoples, having arrived only within the past few centuries. Many Orang Kuala still live on the eastern coast of Sumatra, where they are known as the Duano.

Linguistically, most Proto-Malay groups speak archaic forms of Malay. The main exceptions are the Semelai and Temoq, whose languages belong to the Aslian family, alongside those spoken by the Senoi and Semang.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026