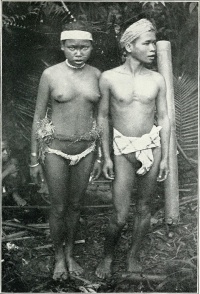

TEMIAR

The Temiar are a group of slash-and-burn farmers that live in the rain-forested mountains and foothills in a 5000 square kilometer area in the interior parts of Perak, Pahang and Kelantan states in peninsular Malaysia. There are about 35,000 of them and they widely dispersed. There is a population density of about two persons be square kilometer, where they live . Their language is classified in the Aslian Branch of the Austroasiatic group of languages. Most also speak some Malay and there are many Malay loan words in Temiar languages. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Temiar are a Senoic group indigenous to the Malay peninsula and one of the largest of the nineteen Orang Asli groups of Malaysia. Many live on the fringes of the rainforest, while a small number have been urbanised. The Temiar are traditionally animists, giving great significance to nature, dreams and spiritual healing.

The Temiar are one of the larger Orang Asli groups of peninsular Malaysia. "Temiar" is an anglicized form of the Semai name for the language spoken by their northerly neighbors. This word has no apparent meaning in any Aslian language, but it likely derives from the Austronesian root “tembir”, meaning "edge." This suggests that an earlier population in the peninsula saw the Temiar as geographically peripheral. ~ The Temiar usually refer to themselves as Sèn'òòy Sròk (the people of the hilly interior) or Sèn'òòy Bèèk (the people of the forest); they call their language Kuy Sròk (hilly interior speech). Since the mid-1960s, they have also begun to refer to themselves by the name that others call them: "Temiar." ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS OF MALAYSIA): LIFE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

SENOI: HISTORY, GROUPS, DREAM THEORY factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MALAYSIA: HARMONY, DISHARMONY, GOVERNMENT POLICIES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

Temiar History

The ancestors of the Temiar are believed to have arrived o the Malaya Peninsula about 8000 to 6000 B.C., perhaps mixing with the Semang people’s who were already there. The Malays arrived millennia later. At first they traded peacefully and mixed with the Senoi but as the Malays grew powerful they carved Malaysia into small states. The Senoi became dependants and second class citizens.

External interference in Temiar life can be dated with certainty to the mid-nineteenth century, when upland Malay leaders known as Mikong asserted authority over Temiar communities. These chiefs controlled trade, intermarried with Temiar women, and acted as intermediaries until World War II, reinforcing social boundaries between Temiar and Malays. At the same time, Temiar villages were periodically raided for slaves by downriver Malays, a practice remembered into the present and often cited as a source of Temiar wariness toward outsiders and strong local communalism. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

From the 1950s onward, the Mikong role was replaced by colonial and later Malaysian state institutions, especially the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (JOA). During the Communist Emergency (1948–1960), Temiar leaders pragmatically maintained relations with all sides to preserve autonomy. In later decades, some Temiar have sought fuller participation in Malaysian society through organizations such as the Orang Asli Association, though traditional leadership structures remain important at the village level.

State policy has strongly shaped Temiar relations with the wider society. The Aboriginal Peoples Act of 1954 (revised 1974) granted authorities control over village access and land allocation, originally for security reasons but later limiting contact and delaying civic integration without securing land rights. Government agencies have variously viewed the Temiar as economically backward, politically suspect, culturally incomplete Malays in need of Islamization, or as obstacles to logging and forest exploitation. Since the mid-1970s, many Temiar have been relocated to permanent settlements built for security purposes.

Anthropologically, the Temiar share genetic and cultural roots with other Orang Asli, Malays, and Southeast Asians, and are likely descendants of populations associated with Hoabinhian and Neolithic archaeological sites in the peninsula. Modern scholarship rejects older theories that treated the Temiar as remnants of a distinct migratory “wave,” instead viewing them as part of a long-standing, locally generated ethnic and cultural continuum shaped by ecological and political processes within the Malay Peninsula.

Temiar Religion

Temiar religion and worldview are centered on lived experience rather than abstract ideas or formal doctrines. They understand the world through personal subjectivity—how it feels to act and to be acted upon at the same time. The self is never seen as separate or autonomous; it always exists in relation to others. Meaning and coherence arise from this constant interaction between self and other, rather than from fixed rules or beliefs. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Temiar believe that people have several souls. These include souls connected with the head and heart. In humans, the hup (heart) is linked to intention and action, while the rwaay (head-soul) is linked to perception and experience. Animals, plants, and even landscape features are believed to possess similar forms of subjectivity. The Temiar also believe in a large numbers of spirits associated with living things, natural phenomena and inanimate objects, which are believed to act as guides for individuals and appear in their dreams. As is true with the Semang and Senoi, the thunder god is of particular importance.

Perhaps because this worldview is complex and hard to articulate, some Temiar began turning toward more clearly defined world religions. in recent decades, In the 1970s many adopted the Baháʼí Faith, which was seen as easier to explain and more compatible with modern life. Others have converted to Islam, sometimes through state pressure. According to the Christian group Joshua Project five to 10 percent aee Christians. Despite these changes, traditional ceremonies centered on spirit mediums, singing, and trance continue in many communities, even among those who follow newer religions.

Temiar and Senoi Dream Therapy

The Temiar put a great deal of emphasis on “lucid dreaming” and trance. Some of their customs have become the inspiration for “Senoi dream therapy” practiced by several groups in the United States. Later research has shown that modern American dream-therapy movements have only a weak, and sometimes misleading, connection to actual Temiar practices. While dreams and trance are genuinely important in Temiar life, their value lies not in therapeutic techniques but in how these experiences connect people directly to what they understand as the fundamental structure of reality. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Religious specialists are usually chosen on the basis of their contact with the spirits in their dreams and ability to go into trances. Dreams and trance are the main ways Temiar communicate with spirit guides. These spirits often appear in dreams and may later assist individuals who become halaa’, or spirit mediums. Mediums lead nighttime ceremonies involving singing, dancing, and sometimes trance, and they may also perform healing rituals. Songs used in ceremonies are believed to be taught directly by spirit guides through dreams.

Trance and lucid dreaming are understood as states in which a person both controls and experiences events at the same time. In these states, individuals directly encounter the same creative processes that are thought to sustain the cosmos itself. This experience is deeply personal and difficult to explain in words, which is why Temiar beliefs are rarely stated explicitly and are instead lived through ritual and practice.

Temiar Ritual Life and Taboos

Spirit possession involving trances are common. Most ceremonies last two to six nights and are organized to cure illnesses. They often feature a great deal of singing and dancing. The Temiar also have a long list of seemingly arbitrary taboos such as not laughing at butterflies or dressing animals in human clothing. Breaking such taboos, they believe, could trigger ferocious storms or floods. To make amends for breaking such taboos individuals can mix some of their blood with water and offer it to the thunder god.

The core ceremonial event in Temiar society is a nighttime gathering inside a house, known as a gnabag (“singsong”). These performances are led by one or more spirit mediums and involve choral singing, dance, and sometimes trance. Ceremonies are organized either in response to illness or because a spirit guide has indicated in a dream that it wishes to be honored. Much of the community participates, with women and children singing overlapping responses to the lead verses. The songs are believed to belong to the spirit guides themselves and are understood to be sung through the medium rather than composed by them.

Taboos include as laughing at butterflies, dressing animals in human clothing, displaying bright mats outdoors, or laughing too loudly. These are considered misik, acts that draw improper attention. Such behavior is believed to risk angering the thunder deity and could bring violent storms or floods. If a storm does occur, individuals who believe they have violated a taboo may attempt to make amends. One method involves drawing a small amount of blood, mixing it with water, and offering it to the thunder deity as an act of appeasement. Other responses include striking the ground with a knife or driving a lock of hair into the soil during severe thunderstorms. Although these practices exist among several Orang Asli groups, they are relatively rare among the Temiar themselves.

Temir Burials and Views on Death

The dead are usually buried on the day of death on the other side of a stream from where people live because it is believed that ghosts can not cross water. The body is wrapped in matting and placed in an alcove within the grave, on a split-bamboo platform. More split bamboo is placed on top, to ensure that the body does not come into direct contact with the soil when the grave is filled in. The grave is usually oriented in line with the sun's track, in accordance with the belief that the deceased will be transported to an afterlife in a special "flower garden" situated at the sunset. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The dead are buried with the forest with most of their valued possession, thereby negated the need for inheritance. The grave is oriented towards the path of the sun because it believed the dead reside in a “flower garden” at the sunset horizon. For several days after the burial fires are lit at the grave site. After that the forest is allowed the reclaim the site. Sometimes respected shaman are buried on a platform on a tree and dead babies are hung in a bag from a branch on the tree.

The Temiar are uncomfortable with memorializing the dead and deliberately avoid developing any form of ancestor cult. They do not speak the names of deceased people. Instead, they refer to them as “Old Man” or “Old Woman” followed by the name of the burial place. Over time, many individuals come to share the same burial name, and detailed personal genealogies fade away. What remains instead is a remembered sequence of former village sites, which helps organize social relationships without focusing on individual ancestors.

This desire to leave death behind was once expressed more dramatically. In the past, Temiar villagers would burn the house of the deceased on the day of death and then move the settlement a short distance away. Today, this practice is rare, largely because people now own more material possessions and prefer to remain where they are.

Other burial practices have also existed. Highly respected spirit mediums (halaaʼ) were ideally placed on platforms in trees after death, while infants might be hung in bags from trees. These customs likely reflect older Southeast Asian traditions of tree burial. In contrast, the burial method most commonly used today appears to have been adopted from Malay Islamic practices.

Temiar Society

The nuclear family and to a lesser extent extended families are the most important social units in Temair Society. There is talk of descent groups but they do not seem to play a big role in how society is organized. In some cases tree-owning rights are passed down from one family member to another. The Temiar abhor violence and have respect for individual autonomy. Groups traditionally have not had a strong head man. When they did the leaders were chosen more on the basis of their verbal skills than wealth or family background. The government has encouraged them to chose leaders. These men are best viewed as intermediaries between the Temiar and outsiders rather than leaders within the community. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Temiar are very egalitarian. Individuals are allowed to what they please as long as they don’t hurt anyone. Children are allowed to run free and even experiment with knives and sex if they so please. Even with these things being they case they usually avoid violence of any kind and even avoid competition. When they play games and sports—even soccer—they play in such a way that everyone helps the group.

The main sources of conflict within Temiar communities have traditionally included sexual jealousy—often linked to the permissive joking relationships between in-laws—economic inequalities arising from uneven participation in the cash economy, and the withdrawal of individuals or families from village life instead of contributing sustained labor and commitment. Because Temiar values discourage the imposition of one person’s will on another, there are few direct means of addressing such tensions. Gossip and private complaints are common, while open confrontation is rare.

When conflicts escalate, the village leader may convene a community meeting. Even then, speakers tend to moralize in general terms rather than accuse specific individuals. If discussion fails to resolve the issue, the usual outcome is for one of the parties involved to leave the village and settle elsewhere.

Underlying Temiar social interaction is a pervasive anxiety that one’s actions might leave another person with unfulfilled desires, a condition believed to expose that individual to illness, misfortune, or accident. To prevent this, a set of diffuse social expectations operates as a form of sanction: food should always be shared; direct requests for help or objects should be honored; and firm future commitments should be avoided, lest they go unfulfilled. These principles are closely intertwined with Temiar religious beliefs and reinforce the broader moral fabric of social life.

Temiar Family and Kinship

Temair residence is organized at three levels: 1) Household – usually one married couple and children; 2) Household cluster – closely related families living together; and 3) Village – seen as one large family unit. In regard to inheritence, traditionally, personal property was buried with the dead. The most important shared property consists of fruit trees, which are owned collectively by sibling groups after the original owner dies.

Temiar villages are built around flexible kin groups based on shared ancestry through both mothers and fathers. People can belong to several such groups, but the one linked to their birth village is usually considered primary. In everyday life, village membership depends less on formal descent and more on ongoing relationships with living relatives. Descent matters mainly when leadership or long-term group continuity is questioned. Leadership normally goes to the most capable senior sibling within the core family group.

Temiar kinship terms are simple and inclusive. Siblings and cousins are treated as the same, and relatives are grouped mainly by generation rather than by exact genealogical distance. All Temiar—and even neighboring groups—are seen as potential kin. Strangers try to find shared relatives and then relate to each other as kin. This allows people to travel widely while creating networks of mutual obligation based on kinship.

The mother and father, their kin and often the whole village shares in child rearing in a kibbutz-like manner. Discipline is gentle and nonviolent, relying on advice rather than punishment. Children enjoy great freedom and learn cooperation early. There are no formal initiation rites, and children learn skills and social rules through experience and storytelling.Today, most Temiar children attend government primary schools in their own area. These provide basic literacy in Malay, though formal education remains limited.

Temiar Marriage and Gender Roles

Marriage are generally fairly casual; and premarital and extramarital sex are common. In many cases a couple becomes “married” when they start sleeping with one another and equivalent word for marry in the Temiar language is:to sleep with.” Sometimes gifts are exchanged but there are generally no significant bride price payments from the groom. If a couple is unhappy with each other they simply move apart, Re marriages are common. Sex and joking about sex among siblings-in-law is Temiar custom. There have been rare cases of polygyny usually involving sisters.[Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Husband–wife relationships are expected to be equal and cooperative, and marriages can end easily if either partner is unhappy. Many people marry more than once. Marriage rules are flexible, guided mainly by closeness of residence, degree of blood relation, and existing marriage ties. Marriage also reshapes relations between families, creating formal rules of avoidance, respect, or joking. In particular, opposite-sex siblings-

After marriage the couple generally lives first with the wife’s group and later with the husband’s group. Most activities, including farming, fishing, cooking, and childcare, are carried out by anyone, regardless of gender. Men do most of the hunting and heavy chores such as house building and felling large trees. Women do most of gathering and basket making. However, women and children catch animals by other means, and men make baskets.

Temiar Life, Villages and Culture

The Temiar have traditionally lived in small villages of 12 to 150 people set up in a clearing in the forest along a stream or river. Their traditional houses are made of wood, split bamboo and bark and have woven, palm-frond shingles. Spaces are left between the split bamboo to allow for the circulation of cooling air. The houses are built on stilts and are between one meter and 4 meters off the ground. The whole structure is held together with tightly knotted rattan strips and requires minimal skills or carpentry tools to build. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Within a traditionally house is a central area for cooking, dancing and threshing. Outside these are smaller compartments for individuals, partners or children. Often they are only separated from the main room by a waist-high partitions. These days most Temiar are settled in Malay-style relocation communities They get around on the rivers in Malay-style dugout boats and bamboo rafts that are only good for going down river.

The Temiar produce abstract and geometrical designs on mats, pouches, walls of houses and blowgun darts. The greatest degree of aesthetic attention is given to the tightly woven rattan caps that cover the geometrically decorated bamboo quivers used by Temiar men to carry their blowgun darts. However, music, dance, and storytelling are also cultivated with enthusiasm, and certain individuals gain considerable local fame for their abilities in these areas. Temiar women are famous for their choral singing. Sometimes they pass around recordings they made themselves.

Ingo Stoevesandt wrote in his website on Southeast Asia music: “Among the Orang Asli music, the Temiar music has become mostly recognized as “healing music” worldwide, but the reasons are questionable, because this “dream music” is often used and sold from the “New Age”and esoteric scene. It also shows a paradigm of the Orang Asli, as they still are classified as leading an “romantic existence” in the jungle, only dependent on the things which nature spends everyday, but this is far from reality, of course. -[Source: Ingo Stoevesandt from his website on Southeast Asia music ]

The Temaire believe illnesses are caused by the improper mixing of contradictory forces. Temiar ideas about disease focus on the belief that illness arises when boundaries between worlds or forces that should stay separate are crossed. This may involve physical spaces, the loss of part of the soul, or the invasion of spirits. As a result, symptoms do not always match biomedical categories, even though they are experienced as very real. Physical problems like joint pain may be explained as the body entering the wrong domain, such as a person’s leg becoming trapped in mud. Treatments involve herbal remedies, shaman rituals and special shaman “blowing.” Such blowings are performed through cupped hands by anyone with shaman powers. Full ceremonial shamanism is performed in a trance by several shaman acting together.

Temiar Economic and Agriculture

The Temiar have traditionally practiced subsistence slash-and-burn agriculture, primarily growing rice and cassava, and hunting and fishing. For income they sell forest products like rattan and “jelutung” (a coagulated tree latex used in some chewing gums). In some places, encouraged by the government, they grow rubber. The Temiar make mats and baskets and other products from bamboo, pandanus and rattan. Metal tools such as knives, spear points and machetes and things like tobacco, flour and cloth are obtained through trading forest products with Chinese and Malay traders. The Temiar traditionally have had no sense of land ownership although they sometimes did lay claim to fruit trees. [Source: Geoffrey Benjamin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Hunting has traditionally been done with blowguns and poison darts and shotguns. Now most animals are caught with snares and traps. Valued catches include deer, wild pigs, pythons and civets. Chickens are raised for food. The Temiar have problems eating other animals because they regard them as pets. Their animals are often sold to the Malays. They fish with drop nets,, barricades and hooks and lines.

For a long time, the Temiar’s main trade product has been rattan, collected from the forest during the farming off-season and sold to outside traders, mainly for furniture making. They also trade jelutong latex, used commercially in chewing gum. In the past, trade was handled by local Malay middlemen; today a government agency plays a similar role. Some Temiar have begun experimenting with making rattan furniture themselves and with small-scale tourism run in cooperation with Orang Asli organizations. Locally, Temiar sell fruit, wild game, rice, and fish. Fishing became especially important for communities near the large reservoir created in the 1970s. In some areas, Temiar tap rubber from small plantations established with outside help, which encouraged more permanent settlement, although low rubber prices have limited its success.

Land as we said above was traditionally not owned. What mattered were rights to products, especially long-lived fruit trees, which could belong to individuals or to descendant groups.These fruit trees are the main way Temiar link families to particular places over time. Outsiders have often misunderstood this system as land ownership, leading to the administrative idea of inherited territorial units. Because Temiar land is not legally recognized under modern law, they have little formal protection when roads are built, forests logged, or valleys flooded. As development expands, disputes over land and compensation are likely to become an increasingly serious problem.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026