SENOI

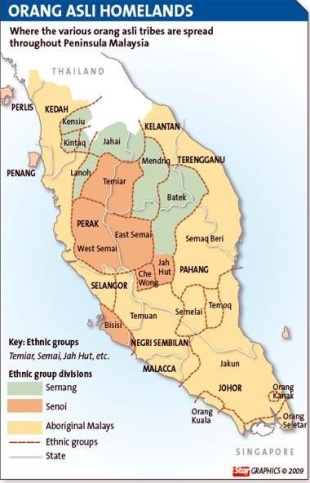

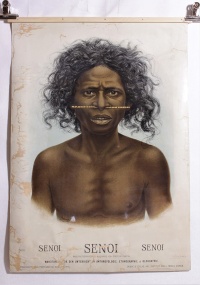

The Senoi are the largest Orang Asli (Malay for “original people” or aboriginals) subgroup in Malaysia, making up about 54 percent of the total Orang Asli population. They comprise six tribes—Temiar, Semai, Semaq Beri, Jah Hut, Mah Meri, and Cheq Wong—who live mainly in the central and northern regions of the Malay Peninsula. Their villages are widely scattered across the states of Perak, Kelantan, and Pahang, including along the slopes of the Titiwangsa Mountains. In physical appearance, the Senoi generally differ from other indigenous groups by being taller, having lighter skin, and wavy hair. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Senoi live mostly in central peninsular Malaysia. They have traditionally been slash-and-burn farmers that live in the rain-forested mountains and foothills of the Main mountains range which bisects the Malaya peninsula, primarily in northeast Pahang and southeast Perak. There are about 60,000 to 100,000 of them depending on how they counted. Senoi have been called Sakai — a derogatory term sometimes described as meaning “slave” by Malays. Its derivative — menyakaikan — means "to treat with arrogance and contempt." However, for the Senoi, "menyakaikan" means "to work together."

Senoi languages are classified as members of the Aslian Branch of the Austroasiatic group of languages. Most also speak some Malay and there are many Malay loan words in Senoi languages. Many have never traveled further than a few kilometers from the place they were born. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS OF MALAYSIA): LIFE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

TEMIAR: HISTORY, SOCIETY AND RICH RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MALAYSIA: HARMONY, DISHARMONY, GOVERNMENT POLICIES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC ISSUES IN MALAYSIA: DISCRIMINATION, SEPARATION, PROTESTS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

Senoi History

The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population.

The Senoi are believed to have arrived o the Malaya Peninsula about 8000 to 6000 B.C., perhaps mixing with the Semang people’s who were already there. The Malays arrived millennia later. At first the Malays traded peacefully and mixed with the Senoi but as the Malays grew powerful they carved Malaysia into small states. The Senoi became dependents and second class citizens. When the Malays converted to Islam they labeled the Senoi as pagans and enslaved them, murdered adults and kidnaped children under the age of nine.

The derogatory term "sakai," used by the Malays for the Senoi people, emerged during the slave period. It means "rough or savage aborigines" or "slaves." Following the British Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire, and the British colonial government made slave raiding illegal in British Malaya in 1883. However, there were records of slave raiding until the 1920s and the slave practice didn’t end until the 1930s in some places. The policy of the Malaysian government has been to “civilize” the Senoi by converting them to Islam and making them ordinary people.

Senoi Groups

The term Senoi has long been applied with inconsistent. They are usually defined by their use of Aslian languages and their reliance on slash-and-burn agriculture, but in practice the group includes peoples speaking different branches of Aslian and with varied subsistence patterns. While the Semai and Temiar fit the classic definition, other groups—such as Cheq Wong, Jah Hut, Semaq Beri, Semelai, Temoq, and Mah Meri—are included for cultural or administrative reasons, despite linguistic or economic differences. Government development and forest clearance have increasingly restricted Senoi territories. [Source: Wikipedia]

Cheq Wong are a small, semi-Negrito group living in a few remote villages on the southern slopes of Mount Benom in western Pahang. Their classification has been problematic, partly due to historical misunderstandings of their name. Traditionally, they depended heavily on gathering forest products. Linguistically, their language belongs to the Northern Aslian branch and is closely related to Semang languages.

Temiar are the second-largest Senoi group and inhabit forested areas on both sides of the Titiwangsa Mountains in southern Kelantan and northeastern Perak. They usually live in isolated upper river regions but maintain contact with neighboring peoples along the periphery of their territory. Their traditional economy centers on slash-and-burn agriculture and trade.

Semai are the largest Senoi group and the largest Orang Asli people overall. They live south of the Temiar, across southern Perak, northwestern Pahang, and parts of Selangor, in environments ranging from remote highlands to urban fringes. Traditionally they practice swidden agriculture and trade, supplemented by wage labor and commercial farming. Semai identity is relatively fluid, with limited sense of a unified group identity across regions. See ORANG ASLI: GROUPS, HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHY LANGUAGES for information on the Semai factsanddetails.com

Jah Hut live on the eastern slopes of Mount Benom in central Pahang, mainly in Temerloh and Jerantut districts. They are eastern neighbors of the Cheq Wong. Their language occupies a distinct position within the Aslian family, and their traditional livelihood is based on slash-and-burn agriculture.

Semaq Beri inhabit interior regions of Pahang and parts of Terengganu. Their name, meaning “jungle people,” was originally applied by colonial administrators. Traditionally, they combined swidden agriculture with hunting and gathering, and some groups were formerly nomadic around areas such as Bera Lake. Other Orang Asli groups sometimes regard them as closely related to the Semelai.

Semelai live mainly in central Pahang around Bera Lake and nearby river systems, with some communities extending into Negeri Sembilan. Officially classified as Proto-Malays, they speak a Southern Aslian language. Unlike many other Senoi, forest gathering was not central to their economy; instead, they practiced agriculture, fishing, and wage labor.

Temoq are a little-known group living near the Jeram River northeast of Bera Lake in Pahang. Although no longer officially recognized as a separate group, they are usually included with the Semelai. Traditionally, they were nomadic and only intermittently practiced agriculture.

Mah Meri live along the coast of Selangor and combine agriculture with fishing. Among the Senoi, they have been most influenced by Malay culture, yet they maintain a strong attachment to their customary lands and generally avoid urban life. Their language belongs to the Southern Aslian branch.

Historical sources suggest that additional Senoi groups once existed, including peoples near Mount Benom and around present-day Kuala Lumpur, speaking languages related to Cheq Wong or Mah Meri. Some Southern Aslian-speaking groups may have disappeared or been absorbed by Austronesian-speaking Temuan and Jakun communities.

Senoi Religion

The Senoi believe in gentle spirits and use taboos to maintain control. Mankind is viewed as alone and vulnerable in the world. The Senoi go through great effort to not offend spirits and the heavenly god that cause thunder and lighting. Religious specialist are usually chosen on the basis of their contact with the spirits in their dreams. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Spirit possessions involving trances are common. The spirts, the Senoi believe, love fragrances and are often attracted with flowers and fragrant leaves. Most ceremonies last two to six nights and are organized to cure illnesses. The biggest festival is held after the rice harvest and is tied in with Chinese New Year celebrations.

The Senoi believe everyone has several souls, including shadow souls that can be malevolent ghosts. The dead are usually buried on the other side of a stream from where people live because it is believed that ghost can not cross water. The dead are buried with some possessions, but they don’t have a clear concept of the afterlife. Six days after the burial feast marks the “close of the grave.” The mourning period last a week to a month and involves taboos on music, dancing and generally having a good time.

Contact with outsiders has introduced competing religious influences into Senoi society. Christian missionaries were active from the 1930s onward and produced the first written texts in Aslian languages. The Malaysian government has promoted Islamization among indigenous peoples, a policy that has often met resistance and caused tensions. The Baháʼí Faith has gained notable influence among the Temiar. Alongside these world religions, syncretic movements have emerged, blending traditional beliefs with Islamic, Buddhist, Hindu, and other elements. According to official statistics, most Orang Asli remain animists, accounting for nearly 77 percent of the population. Muslims form about 16 percent, Christians around 6 percent, and Baháʼís roughly 1.5 percent, with very small numbers identifying as Buddhists or followers of other religions. [Source: Wikipedia]

Senoi Dream Theory

The Senoi have traditionally believed that people become “adepts” through relationships with familiar spirits. A familiar appears in dreams, drawn to the dreamer’s body, and if the dreamer chooses to accept it, the person becomes an adept. With the help of the familiar, adepts are able to diagnose and cure illnesses believed to be caused by pain spirits. Women may decline this calling because trance states are physically exhausting, though some nevertheless become adepts in their role as midwives. Midwives and adepts commonly marry one another. Spiritual knowledge gained through contact with familiars and expressed in dreams is highly valued, and disputes could arise if a man was accused of presenting his wife’s dreams as his own. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

In the 1960s, the so-called Senoi Dream Theory gained popularity in the United States. This theory promoted the idea that people could learn to consciously control their dreams in order to reduce fear and increase pleasure, particularly sexual pleasure. According to these accounts, the Senoi were said to practice systematic dream control and to use dreams for practical and social purposes. After breakfast, community members supposedly gathered to recount their dreams, discuss their meanings, and decide how to respond to them. Open discussion of dreams was presented as a key mechanism for maintaining social harmony and resolving conflicts, and was credited with making the Senoi exceptionally healthy and psychologically well balanced. [Source: Wikipedia]

These ideas were largely based on the writings of Kilton Stewart (1902–1965), who lived among the Senoi before the Second World War and described them in his 1948 doctoral thesis and his 1954 popular book “Pygmies and Dream Giants”. Stewart’s work was later promoted by figures such as parapsychologist Charles Tart and educator George Leonard, particularly through the Esalen Institute, and further popularized in the 1970s by Patricia Garfield, who wrote about Senoi dream practices based on her encounters with Senoi patients at an aboriginal hospital in Gombak, Malaysia, in 1972.

In 1985, G. William Domhoff challenged many of these claims, arguing that anthropologists working with the Temiar reported that while lucid dreaming was known, it was not especially important in everyday life. Others have countered that Domhoff’s critique overstated the case. Domhoff himself did not deny that dream control is possible or that it can be therapeutically useful, particularly in treating nightmares, citing work by psychiatrists Bernard Kraków and Isaac Marks. However, he questioned broader claims made by the DreamWork movement, especially the idea that group dream discussions, rather than individual motivation and aptitude, significantly enhance the ability to dream lucidly or to do so consistently.

Senoi Fears, Ghosts and Dangerous Spirits

In Senoi belief, the world is filled with dangerous spirits known as mara’, a term meaning “those who kill and eat us.” These include both wild animals—such as tigers, bears, and elephants—and supernatural beings. Mara’ are thought to cause illness, accidents, and misfortune and are considered unpredictable and malicious. Protection comes from friendly spirits called gunig or gunik, which act as guardian or familiar spirits and can be summoned to counter harmful forces. Other benevolent spirits are believed to assist with work, hunting, and personal matters.

Because spirits are thought to be timid, ceremonies are usually held at night. Ritual spaces are decorated with flowers and aromatic leaves to attract and please spirits, and singing and dancing are used to reassure them. Such ceremonies, which may last from two to six nights, are typically performed to heal illness or restore spiritual balance to individuals or communities. Thunder is particularly feared, and individual “blood sacrifices” may be made to calm storms.

Senoi social norms strongly prohibit interpersonal violence, both within the community and toward outsiders. This tradition may be rooted in historical experiences of persecution, including raids by Malay slave hunters. As a result, avoidance rather than confrontation became a key survival strategy. Groups such as the Cheq Wong emphasize strong tribal identity and physical distance from mainstream society. Senoi people generally prefer to withdraw from conflict and openly acknowledge fear as a natural response to danger.

Fear is transmitted across generations, especially to children, who are considered particularly vulnerable. Senoi do not punish or coerce children; instead, behavior is regulated through taboos and cautionary stories about spirits, tigers, and thunderstorms. Children are taught from an early age to fear strangers and to avoid actions that might provoke spiritual harm.

Aside from fear, overt emotional expression is uncommon among the Senoi. Displays of anger, grief, joy, or even laughter are typically restrained, and emotions are rarely shown openly in interpersonal relationships. Expressions of affection, empathy, or compassion tend to be subtle rather than demonstrative.

Senoi Society, Family and Culture

The nuclear family and to a less extent extended families are the most important social units in Senoi society. There is talk of descent groups but they do not seem to play a big role in how society is organized. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Senoi are very egalitarian. The Senoi fear violence and have respect for individual autonomy. Groups traditionally have not had a strong head men. Groups form and break up as need applies. The government has encouraged them to chose leaders. When they did the leaders were chosen more on the basis of their verbal skills than wealth or family background.

Marriages are generally fairly casual; divorces are common and sometimes brothers practice a form of wife swapping. Some practice modified Malay wedding ceremonies. Some require a bride price form the groom. After marriage the couple generally lives first with the wife’s group and later with the husband’s group. Some activities and chores are done by both men and women. Men do most of the hunting and heavy chores such as house building and felling large trees. Women do most of gathering and basket fishing.

The Semai are known for their nose flute playing. Traditional Orang Asli dances are closely associated with shamanic practices and rites of passage involving the spirit world. Among these dances are the Gengulang of the Semai, the Gulang Gang of the Mah Meri, the Berjerom of the Jah Hut, and the Sewang, performed by both the Semai and the Temiar. The only major annual ceremony is the post-harvest festival, which today is synchronized with Chinese New Year. [Source: Wikipedia]

Childbirth is surrounded by special rituals. Pregnant women usually continue their normal work until delivery, which takes place in a specially constructed hut under the supervision of midwives. Immediately after birth, the child is given a name. These practices emphasize continuity with tradition and the protection of both mother and child.

Senoi Life

The Senoi have traditionally lived in settlements with 30 to 200 people set up on the high ground above the junction of a stream and a river. They live in single family or extended family homes set up around a long house that serves as a community meeting place. Their traditional houses are made of wood, bamboo and bark and haven wove, palm-frond shingles. The houses are built on stilts between one meter and 3½ meters high. In places where there are tigers and elephants they can be up to nine meters high. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Traditionally the Senoi settled in one area for three to eight years and then moved on after the soil became exhausted. These days more are settled. Some live in permanent villages where wet-land rice irrigation is used. Some live in semi-permanent settlements and move to slash-and-burn sites during the planting and harvest season. They get around on the rivers in bamboo rafts.

Within their customary territories, Senoi communities manage fruit trees from which they harvest seasonal crops. Bamboo, rattan, and pandan are the principal raw materials for Senoi handicrafts. Bamboo, in particular, is indispensable: it is used in house construction, household utensils, boats, tools, weapons, fences, baskets, water channels, rafts, musical instruments, and jewelry. The Senoi are especially skilled basket weavers, with the most elaborate techniques found among more settled groups. River travel is usually by bamboo raft, and less commonly by dugout canoe. The Senoi traditionally did not practice pottery, textile weaving, or metalworking. Clothing made from the bark of four tree species survives today mainly in ritual contexts.

Modern Senoi who have regular contact with Malays generally wear clothing typical of the wider Malaysian population. In more remote areas, however, men and women may still wear loincloths made from narrow bands of bast fibre around the waist. The upper body is often left uncovered, though women sometimes cover their breasts with a narrow strip of cloth. Tattoos and body painting remain common, and noses may be pierced with decorated porcupine quills, bone, bamboo, sticks, or other ornaments. Facial and body tattoos are usually believed to have magical or protective meanings. [Source: Wikipedia]

Senoi Agriculture and Economic Activity

The Senoi have traditionally practiced subsistence slash-and-burn agriculture, primarily growing rice, maize and manioc, and hunting and fishing. For income they sell forest products like rattan, resin and wild bananas. Settled communities maintain fruit groves. In some places, encouraged by the government, they grow rubber. The government does not recognize Senoi land rights. Among slash-burn practitioners, groups only had rights to land while it was being cultivated. [Source: Robert Knox Dentan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Senoi grow crops in such a way that they can harvest them year round and always have a food supply no matter what happens. Pests include rats, grain-eating birds, deer and elephants. There are also problems with “lalang” grass. Basket traps are the primary fishing device. Poisons, weirs, hooks, spears, corrals and baskets are also used. The Senoi are very fond of the honey of wild bees. The Senoi also keep domesticated animals, including chickens, goats, ducks, dogs, and cats. Chickens are raised primarily for household consumption, while goats and ducks are often sold to neighboring Malay communities.

The Senoi make mats and baskets and other products from bamboo, pandanus and rattan. They used make cloth from bark but now clothes made from such materials are only used in ceremonies. Metal tools such as knives, spear points and machetes and things like tobacco, flour and cloth are obtained through trading fruits, lumber, butterflies, resin and rattan with Chinese and Malay traders.

Senoi Food and Hunting

Although plant foods form the basis of the Senoi diet, meat is highly valued. Expressions such as “I haven’t eaten in a few days” often mean that a person has gone without meat, fish, or poultry rather than food in general. This preference reflects the cultural importance placed on animal protein, even when it is scarce.

Hunting used to done with blowguns and poison darts. Now most animals are caught with snares, spear traps, birdlines, and deadfalls. Valued catches include deer, wild pigs, pythons and civets. Chickens are raised for food. Goats and ducks are raised for sale to the Malays.

Traditionally, Senoi hunting relied on blowguns fitted with poison darts, objects that carry deep cultural significance and are a source of great pride for men. Blowguns are carefully polished, decorated, and treated with affection; a man might devote more time to perfecting a blowgun than to building a new house. They are mainly used to hunt small game such as squirrels, monkeys, and wild boar. [Source: Wikipedia]

Successful hunters are welcomed back with enthusiasm, often accompanied by dancing. Larger animals—such as deer, wild boar, pythons, and binturongs—are usually taken using traps, snares, or spears. Birds are caught with ground-set noose traps, while fish are mainly captured using basket traps placed in rivers. Other techniques include the use of poison, dams, fences, spears, and hooks.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026