SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE

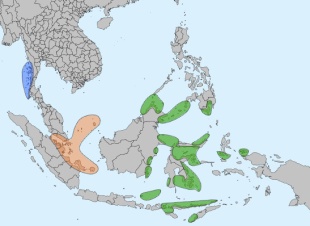

The term Sama-Bajau is used to describe a diverse group of Sama-Bajau-speaking people who are found in a large maritime area with many islands that stretch from central Philippines to the eastern coast of Borneo and from Sulawesi to Roti in eastern Indonesia. The Sama-Bajau people usually call themselves the Sama or Samah (formally A'a Sama, "Sama people") and have traditionally been known by outsiders as Bajau (also spelled Badjao, Bajaw, Badjau, Badjaw, Bajo or Bayao). They have also been Sea Gypsies, Sea Nomads and Samal as well as Sama Moro and Turijene in the Philippines, Luwa’an, Pala’au, Sama Dilaut and Turijene in Indonesia, and the Bajau Laut in Malaysia. Some of these names refer to Sama-Bajua subgroups. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Sama-Bajau speakers are probably the most widely dispersed indigenous ethnolinguistic group in Southeast Asia. Their settlements are scattered throughout the central Philippines, the Sulu Archipelago, the eastern coast of Borneo, Palawan, western Sabah (Malaysia), and coastal Sulawesi. They also have small enclaves in Zambales and northern Mindanao. In the Philippines, most Sama speakers are referred to as "Samal," a Tausug term also used by Christian Filipinos, with the exceptions of Yakan, Abak, and Jama Mapun. In Indonesia and Malaysia, related Sama-speaking groups are known as "Bajau," a term of apparent Malay origin. In the Philippines, however, the term "Bajau" is more narrowly reserved for boat-nomadic or formerly nomadic groups referred to elsewhere as "Bajau Laut" or "Orang Laut."

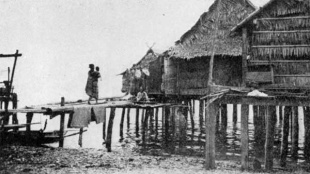

For most of their history, the Sama-Bajau have been nomadic seafaring people who live off the sea through trade and subsistence fishing. They have traditionally stayed close to shore with houses on stilts and traveled, and sometimes lived in, handmade boats lepa. Sama-Bajau are the dominant ethnic group in Tawi-Tawi islands and are generally associated with the Sulu islands, the southernmost islands of the Philippines. They are also found in the coastal areas of Mindanao and other islands in the southern Philippines, as well as in northern and eastern Borneo, Sulawesi, and throughout the eastern Indonesian islands. Most Sama-Bajau are Muslims. In the Philippines, they are grouped with the Moro people, who have similar religious beliefs. Some Sama-Bajau groups native to Sabah are also known for their traditional horse culture. The Orang Laut and Moken are two other traditional sea-based peoples. The Orang Laut have traditionally lived southern peninsular Malaysia, southeastern Sumatra and Singapore. The Moken live in southern Myanmar and western Thailand.

The Sama-Bajau are a highly fragmented people who are unified by their traditional seafaring ways and Sama-Bajau languages. They usually identify themselves with their dialect and the area they are based and have links to their country that has domain over their base islands and the dominant ethnic groups on their base islands— the Tausug and Maguindanao in the southern Philippines, Malaysians and Bruneians in western Sabah, and the Ternatans, Bugis and Makassarese in eastern Indonesia. Notable Sama-Bajau groups include the Abak of Capul Island, northwest of Samar; the Takan of Basilan Island and coastal Zamboanga.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

MOKEN SEA NOMADS: HISTORY, LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MOKEN IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

Sama-Bajau Populations

According to 2010 census data the total population of Sama-Bajau is around 1.3 million, with 499,620 in the Philippines, 456,672 in Malaysia, 241,836 in Indonesia and around in 12,000 Brunei. Since the 1970s, many of the Filipino Sama-Bajau have migrated to neighbouring Sabah and the northern islands of the Philippines, due to the conflict in Mindanao. As of 2010, they were the second-largest ethnic group in Sabah. [Source: Wikipedia]

Boat-dwelling groups have never, from the earliest historical evidence available, constituted more than a small fraction of the total Sama-Bajau-speaking population. However, their numbers have declined rapidly in the last century, and today they probably amount to fewer than 10,000. In eastern Indonesia, the Sama-Bajau as a whole, including both nomadic and sedentary groups, number between 150,000 and 200,000, and in Sabah, approximately 120,000, including at least 30,000-40,000 recent Philippine migrants. ~

In the 1970s, the Sama-Bajau , who are referred to as "Samal", were largest Sama-Bajau group in the Philippines, with an estimated 243,000 people in 1975. At that time in the Philippines the Yakan population was over 115,000, and the Jama Mapun population was about 25,000, including an estimated 5,000 individuals in Sabah. The total Bajau population in Sabah was nearly 73,000 in 1970, excluding recent immigrants from the Philippines. These immigrants comprised an additional 30,000 to 40,000 people (a conservative estimate). There are no reliable population figures for eastern Indonesia in the 1970s.

In the 1990s, there were around 700,000 Sama-Bajua speakers, with maybe 300,000 Samal, 130,000 Yakan; and 30,000 Jama Mapun in the Philippines. There were maybe 80,000 Sama-Bajua in Sabah in the 1990s and between 150,000 and 200,000 in eastern Indonesia. The largest Sama-Bajau communities in Indonesia are in Sulawesi. They are also found near Balikpapan in East Kalimantan and islands off the east Borneo coast. Other are widely scattered on islands between the Moluccas and Timor and around the islands of Nusa Tengarra (the islands east of Bali).

Sama-Bajau Languages

The Sama–Bajau peoples speak a subgroup of Austronesian languages commonly referred to as Sama–Bajau or Sinama, belonging to the Western Malayo-Polynesian branch. Around ten closely related languages are usually distinguished, many of them highly dialectalized, and most Sama–Bajau speakers are multilingual. In Malaysia these languages are often called Bajau, while Sinama is the most widely used collective term in linguistic literature. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The Sama-Bajau languages were once classified under the Central Philippine languages of the Malayo-Polynesian geographic group within the Austronesian language family but are now generally treated as a distinct family due to significant differences with neighboring languages. In the Philippines for instance, the Sinama pronunciation differs greatly from that of other nearby Central Philippine languages, such as Tausūg and Tagalog. Rather than placing the primary stress on the final syllable, Sinama places it on the second-to-last syllable of the word. This placement of the primary stress is similar to that of the Manobo language and other languages of the predominantly animistic ethnic groups of Mindanao, the Lumad peoples.

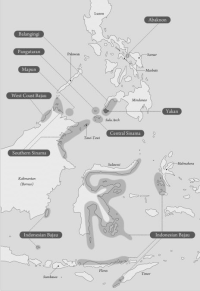

The most divergent members of the Sama-Bajau language group include Abaknon (spoken by the Abak of Capul, Northern Samar), Yakan, and Sibuguey Sama, the latter spoken by several small and relatively isolated communities around Sibuguey Bay in western Mindanao. Western Sama is spoken in North Ubian and the Pangutaran island group west of the main Sulu chain, with smaller numbers of speakers in northern and western Sabah.

More closely related varieties include Northern Sama, spoken mainly in the islands of the Basilan Strait (including Balanguingui), and Central and Southern Sama, which are spoken in the Tapul, Tawi-Tawi, and Sibutu island groups and along the adjacent eastern coast of Sabah from Kudat to Tawau. In Sabah these two varieties are often grouped together as East Coast Sama-Bajau and show strong links with related dialects in the neighboring Sulu Archipelago. A separate language, West Coast Sama-Bajau, is spoken along the western and northern coasts of Sabah from Kuala Penyu to Terusan, with some overlap with East Coast varieties in the north.

In eastern Indonesia, from Sulawesi and eastern Kalimantan to Timor, Sama–Bajau speakers use what appears to be a single language with only minor dialectal variation, generally referred to as Indonesian Sama-Bajau. Although all populations commonly labeled “Bajau” are Sama–Bajau speakers, not all Sama–Bajau speakers identify as Bajau; several groups, including the Yakan and Abaknon, are rarely described by that ethnonym.

Recent linguistic research also shows that the boat-nomadic Bajau Laut are not linguistically homogeneous, nor are they clearly distinct from neighboring shore-based Sama communities. Bajau Laut in Semporna and southern Sulu typically speak Southern Sama, while those in western Tawi-Tawi and central and northern Sulu speak varieties of Central Sama. Apart from the major East–West division in Sabah, locally contiguous dialects—whether spoken by settled land-based communities or by boat-nomadic and semi-nomadic groups—are generally mutually intelligible and tend to grade into one another without sharply defined linguistic boundaries.

Origin of the Sama-Bajau

Scholars have proposed several theories about the origins of the Sama-Bajau. Early views differed sharply: David E. Sopher (1965) suggested descent from ancient “Veddoid” hunter-gatherers from the Riau Archipelago who later intermarried with Austronesians, while Harry Arlo Nimmo (1968) argued that the Sama-Bajau were indigenous to the Sulu Archipelago, Sulawesi, and Borneo and developed their boat-dwelling lifestyle independently of the Orang laut. A 2021 genetic study shows that some Sama-Bajau have Austroasiatic ancestry. The Austronesian people are a vast, diverse group from Taiwan who migrated across Southeast Asia, the Pacific, and include the Malays of Indonesia, Philippines and Malaysia, [Source: Wikipedia]

The most widely accepted hypothesis, proposed by Alfred Kemp Pallasen (1985), dates Sama-Bajau ethnogenesis to around 800 AD. He argued that they originated from a proto–Sama-Bajau population in the Zamboanga Peninsula that combined fishing with slash-and-burn agriculture. From there, some groups adopted an exclusively maritime lifestyle and spread from the 10th century onward to Basilan, Sulu, Borneo, and Sulawesi. These communities were established in the region before the arrival of the Tausūg in the 13th century and later experienced strong Malay, Indianized, and Islamic influences, while engaging in long-distance trade.

Genetic studies add complexity to this picture. Research on Indonesian Bajo groups suggests an origin in southern Sulawesi, with migration to eastern Borneo around the 11th century and onward to northern Borneo and the southern Philippines in the 13th–14th centuries, alongside extensive local admixture. A 2021 genetic study identified a distinct “Sama ancestry,” tracing part of their lineage to ancient Austroasiatic-affiliated hunter-gatherers who migrated through Sundaland 15,000–12,000 years ago and later mixed with Negrito and Austronesian populations. This ancestry is strongest among the Sama Dilaut but is also present among related and neighboring groups across the southern Philippines and eastern Indonesia.

History of the Sama-Bajau

Based on linguistic evidence, the Sama-Bajau are believed to have originated in southwestern Mindanao and the northeastern islands of the Sulu archipelago, and began dispersing in the A.D. 1st millennium. According to legend the event was triggered by the loss or abduction of a princess. Most moved southward and westward towards Borneo and, later, Sulawesi, and appear to have been motivated by Chinese trade and the pursuit of maritime resources. Early groups carved out ecological niches for themselves, with some falling into land-based groups while others being part of sea-based ones. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Sama-Bajau’s place in the world and their migration patterns were affected by the rise of the Tausug dynasty in the 13th century, the founding of the Sulu and Brunei sultanates of the 15th century and the bech-de-mer trade and competition from Bugis and Makassarese trades. Bech-de-mer (sea slugs) are a Chinese culinary delicacy and purported aphrodisiac.

With the rise of the Tausug port of Jolo as a major entrepot for slaves, the Sama-Bajau in some areas became actively engaged in piracy and the slave trade and conducted regular slaving raids until their operation was shut down by the Spanish in 1848. In the past, the Sama-Bajau were generally cordial among themselves but rival regional leaders frequently competed for influence, and many constructed stone or coral forts (kuta’) as refuges during raids or interregional feuds. Among shore-based groups, vendettas could sometimes lead to prolonged hostility, but sustained warfare was uncommon.

The secessionist conflicts in the Sulu archipelago in the 1970s resulted in the dislocation of thousands of Sama-Bajau. Many fled to Zamboanga, Taitawi and the Subutu group or crossed the Malaysia border into eastern Sabah. At the same time large numbers of Tausuh moved from Jolo and Siasi, centers of Islamic extremism, onto the former Sama-Bajau islands of Tawitawi and Sibutu, forcing more Sama-Bajau to migrate westward to Sabah, where they became regarded as refugees.

Sama-Bajau Religion

Most Sama-Bajau are Sunni Muslims of the Shafu school. Every Sama-Bajau parish contains a mosque, which is a center of worship and community activity. The Five Pillars of Islam are acknowledged and Muslim religion days such as Ramadan are observed. Few can afford to make the pilgrimage to Mecca and only the most pious regularly observe all five daily prayers. Mosque officials are appointed by parish elders. Religious officials known as “paki” preside over various ceremonies and serve as religious counselors. Allah is called Tuhan. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The feast day (Hari Raya Puasa, Eid) marks the end of Ramadan; a feast of sacrifice (Hari Raya Hadji) is held during the month of Jul-Hadj; and the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad (Maulud) is recognized. A day of ritual bathing (Tuak Bala'), usually performed in the sea, takes place to remove evil during the month of Sappal. ~

Claims to religious piety and learning are an important source of individual prestige. Persons considered to be descendants of the Prophet are shown special deference. Perceived differences in the practice of Islam are also associated with the relative status of different Bajau groups. Those most closely identified with the region's historical trading states are generally considered the most orthodox. The Bajau Laut, the most peripheral group, are seen by others as living outside the faith and are considered non-Muslims. Due to their nomadic lifestyle, Bajau Laut moorage groups lack mosques.

Pre-Islamic beliefs about spirits and ghosts remain. Most spirits are regarded as malevolent. Mediums, diviners and herbalist-healers are consulted for health problems. The sick are treated with trance dances performed by cloth-waving shaman. Pakis preside over all rites for life crises, act as religious counselors, and conduct minor thanksgiving rites (dua'a salamat). These rites are performed to fulfill a pledge (janji), which is made in exchange for a special favor, such as recovery from an illness or a safe return from a difficult journey.

Islamic burial customs are practiced. The deceased are buried under grave of crushed coral and sand with their heads facing Mecca. Sometimes they are buried on special islands with betel nut boxes. For seven nights after the burial family members gather and read passages from the Koran. During the month of Shaabam God, the Sama-Bajau believe the souls of the dead return to earth and at this times graves are cleaned and special prayers are said. In the past Sama-Bajau cemeteries were located on uninhabited islands reserved for the dead, but now most are located near settlements

Sama-Bajau Economics Activity

Sama-Bajau have traditionally made their living from fishing, farming, seafaring and trade, and sometimes piracy and smuggling. The nature of their work is often defined by where they live and who their neighbors were. Some Sama-Bajau in the Sulu islands run guns between Borneo and Muslim insurgencies in the southern Philippines [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

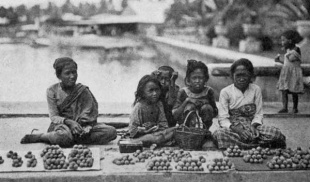

Sama-Bajau fish using traps, spears, hand lines, long lines, drift nets and explosives. They catch dolphins and other sea mammals and sea turtles and collect shellfish, crustaceans, turtle eggs, sea urchins, pearls, mother-of-pearl, and edible algae and sea weed. Drift netting is often done with the fall tide, especially during new and full moons. Most fish are dried and salted for sale in markets. Many earn money from shark fins. Coconuts are a major cash crop for land-based Sama-Bajau. They also grow dry rice, maize, beans, sugarcane and other crops.

Property rights are exercised in connection with fishing grounds and reefs and farms and residential land. Among nomadic groups overlapping fishing grounds have generally invited cooperation rather than fueled feuds. Inheritable possessions includes livestock, farm land. fishing boats, jewelry and gongs.

In Sulawesi Sama-Bajau still dive for trepang, pearls and other marine products. When Chinese and Bugis introduced compressed air, which allowed them to dive longer they failed to explain about the bends properly. In one area alone more than 40 men were killed and a large number were crippled for life. Today they swim sometimes using homemade wood and glass goggles and handmade spear guns and little else.

Most groups practice some kind of farming. Different groups specialize in producing different crafts such as pandanus mats, pottery, roofing, weaving, blacksmithing, and making shell bracelets, tortise shell combs and other items. Boat-building is an especially valued skill. The Sibuti Sama-Bajau are known as being the best Sama-Bajau boat builders. Trade is important to the Sama-Bajau, who have traditionally relied on it even for necessities. They traditionally traded with all comers and exchanged products they gathered from the sea for things like grain and fruit. They also acted as middlemen for trade between other groups.

Sama-Bajau Fishing

The range of marine life exploited by Sama-Bajau fishers is exceptionally broad, encompassing more than 200 species of fish, numerous kinds of shellfish and crustaceans, dolphins and other marine mammals, sea turtles—taken for their shells, eggs, and egg sacs—sea urchins, and edible seaweeds. Fishing gear is equally varied and includes driftnets and liftnets, spears and spearguns, handlines and longlines, traps, harpoons, lures and jigs, as well as explosives and poisons. Since the 1950s, major technological changes have reshaped fishing practices, notably the adoption of manufactured nylon nets, the use of explosives, and the spread of motorized boats. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Fishing activity is closely attuned to environmental rhythms, including tides, monsoonal and local winds, currents, pelagic fish migrations, and the monthly lunar cycle. Driftnetting is most commonly carried out on falling tides, with preferred periods coinciding with the new moon, full moon, and late-rising or “dark” moon phases. On moonless nights, fishers often work by lantern light, using spears and handlines, with catches that include skates, cuttlefish, and squid. Ebb tides are especially important for gathering and for diving for shellfish, as well as for inshore and beach netting. In exposed areas, seasonal monsoon winds may require shifts in fishing grounds or even temporary suspension of fishing during periods of heavy seas.

Today, fishing is largely oriented toward the market economy. Most catches are preserved by salting or drying, though villages close to urban centers may sell fresh fish directly to retailers or to local middlemen supplying export markets. In the Philippines, the introduction of agar-agar aquaculture in the mid-1970s profoundly altered the economy of southern Sulu. Combined with secessionist conflict and rapid population growth, it triggered large-scale migration by Tausug and Sama-Bajau from central Sulu into the southern Sibutu and Tawitawi islands. This influx displaced many Bajau Laut from their traditional fishing grounds, forcing significant numbers to migrate as refugees to southeastern Sabah. There, their arrival has further increased pressure on an already expanding fishing population, placing the region’s coral reefs—long a source of protein and trading wealth—under growing threat of degradation.

Among boat-dwelling and strongly maritime communities, fishing grounds are generally open to common use. For the Bajau Laut, fishing areas often overlap, encouraging cooperation between families from neighboring moorage groups, especially during large-scale fish drives. In contrast, among more settled fishing populations, specific sites such as fish traps, liftnet locations, and artificially constructed fish corrals are subject to individual ownership, while most other fishing grounds remain unowned.

Sama-Bajau, Piracy and Terrorism

Historically, the Sama-Bajau were frequently mentioned in connection with sea raids (mangahat), piracy, and the slave trade in Southeast Asia during the European colonial period. This indicates that some Sama-Bajau groups from northern Sulu, such as the Banguingui, were involved, as were non-Sama-Bajau groups like the Iranun. Their pirate activities were extensive; they commonly sailed from Sulu to the Moluccas and back. They may also have been the pirates described by Chinese and Arabian sources in the Straits of Singapore in the 12th and 13th centuries. Sama-Bajau typically served as low-ranking crew members on war boats under the direct command of Iranun squadron leaders. These leaders answered to the Tausūg datu of the Sultanate of Sulu.

In recent decades, the Sulu islands between the Philippines and Sabah has been the site of pirate activity and a base for terrorist groups. It is not unusual for boats to go missing on perfectly fine days. Many of the pirates have normal day jobs when they are on land. The Sulu Islands are about 1000 kilometers southwest of Manila). The southernmost islands of the Philippines, they are regarded as the most dangerous part of the Philippines and have traditionally been the stomping grounds of pirates and smugglers running guns between Borneo and Muslim insurgencies in southern Philippines. Gun culture is very prominent. Almost everyone has access to a gun. Children learn to handle guns at an early age.

Basilan (30 minutes by ferry and 10 miles from Mindanao) is mostly Christian. It should be a tourist paradise. It has white sand beaches, magnificent rain forests and volcanic highlands with waterfalls. But instead it is a lawless place where Abu Sayyaf hostages have been kept. Jolo has been regarded for centuries a center of piracy, banditry and rebellion. The islands between the Sulu and Celebes Seas have been a hideout for pirates. Jolo and Basilan are the bases for the Muslim terrorist group Abu Sayyaf Since the 1970s, many of the Filipino Sama-Bajau have migrated to neighbouring Sabah and the northern islands of the Philippines, due to the conflict in Mindanao and tensions in the Sulu Islands.

The Tausug are the most dominant ethnic group in the Sulu Islands and are present in large numbers in southern Mindanao. Also known as the Joloanos, Jolo Moros, Suluk, Suluk Moros, Sulus and Taw Sug, they are a Muslim seafaring people that once presided over an empire that stretched from the southern Philippines to Borneo. They have traditionally occupied parts of the coastline suitable for agriculture, leaving the low islands and coastlines to the Samal. The Tausug are regarded as the ones most involved in piracy and smuggling Unlike their Tausūg neighbors, the Sama-Bajau have generally not been characterized by endemic armed conflict, though piracy and occasional vendettas did occur.

See Sulu, Basilan and Jolo Islands: Pirate and Terrorist Hideouts Under MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

Modernization of the Sama-Bajau

Modern Sama-Bajau communities are widely described as peaceful and hospitable, but many face persistent poverty, low levels of formal education, and social marginalization, conditions often linked to the decline of their traditional nomadic maritime lifestyle. The number of Sama-Bajau who live primarily at sea has steadily decreased, driven by cultural assimilation, modernization, and especially the collapse of the Sulu Sultanate, which once supported their barter-based economy. The shift to cash-based fish markets has further pushed them toward sedentary, land-based living.[Source: Wikipedia]

Modern Sama-Bajau continue to navigate profound social, economic, and political challenges as they adapt to life within modern nation-states while seeking to preserve elements of their maritime heritage. Modern national borders have cut across their traditional fishing and roaming grounds, restricting access to livelihoods and exposing them to arrest, boat confiscation, and destruction. Loss of access to marine resources has contributed to the association of some Sama-Bajau communities with illegal or destructive fishing practices, often as a survival strategy in increasingly crowded and regulated waters.

Many Bajau Laut families in Borneo have abandoned life on a houseboat and now live in a stilt house over shallow water. Lepas, the traditional houseboats, are expensive and difficult to build, and with fishing incomes now so limited, most families can no longer afford to maintain them. As fishing and seafaring become less viable, many young people are drawn ashore in search of work, particularly in the tourism sector. [Source Rebecca Cairns, CNN, November 22, 2024]

The declining health of the marine environment and the growing scarcity of fish have left many low-income fishers increasingly desperate. In order to compete with expanding commercial fisheries, some have turned to illegal and destructive practices, such as blast fishing and cyanide fishing, to boost their catches. “Fish bombing is cheap and easy,” says Fatta. A single homemade bomb may cost around 15 Malaysian ringgit (about US$3.60), yet can yield fish worth between 2,000 and 3,000 ringgit (roughly US$480–720). Such practices have been present in the region for decades, with devastating consequences. By 2010, an estimated 68 percent of Sabah’s coral reefs had been damaged by cyanide fishing, and between 2010 and 2018, about a quarter of the state’s monitored reefs were affected by blast fishing.

Governments and NGOs in Indonesia and the Philippines have introduced programs to address these issues, including alternative livelihoods, sustainable fishing initiatives, schools, health centers, and the distribution of boats and fishing gear. In the Philippines, public attention following viral media coverage of a Sama-Bajau girl in 2016 helped spur renewed assistance efforts.

Discrimination and Problems Faced by the Sama-Bajau

In Sabah, many Sama-Bajau—particularly West Coast groups—have faced long-standing land-rights problems. Their customary land has often gone unrecognized by the state, leading to evictions, overcrowding, and resettlement on government land. As a result, Sama-Bajau villages are sometimes misidentified as squatter settlements, deepening marginalization. Similar resettlement policies in Malaysia and Indonesia have pressured Sama-Bajau communities to abandon boat-dwelling lifestyles, with mixed success. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the Sulu Archipelago, the Sama-Bajau have historically suffered discrimination from the dominant Tausūg, who regarded boat-dwelling Sama-Bajau as socially inferior. These attitudes persist in parts of the modern Philippines, where Sama-Bajau communities are often subjected to prejudice, violence, and exploitation, including attacks by insurgent and pirate groups. Ongoing conflict in Muslim Mindanao since the 1970s has displaced tens of thousands of Sama-Bajau, many of whom fled to Sabah, Indonesia, or other parts of the Philippines.

Migration has brought new challenges. In Malaysia, many Sama-Bajau migrants are classified as undocumented, while in the Philippines they are often stereotyped as beggars or squatters. Despite government and NGO initiatives, discrimination remains widespread, including religious stigmatization in parts of the southern Philippines and negative stereotypes in Indonesia.

Impact of Climate Change and Pollution of the Sama-Bajau

Rebecca Cairns of CNN describes how, for generations, the family of 20-year-old Bilkuin Jimi Salih has lived in close rhythm with the sea, marking time by the tides and seeking the protection of water spirits for travel, fishing, and diving. Their way of life has traditionally been low-impact: they harvested only what was needed for survival, moving from reef to reef as fish shoals shifted and allowing marine ecosystems time to recover. Today, however, climate change, pollution, and overfishing are placing unprecedented pressure on the marine environment, and the traditions of the Bajau Laut are rapidly eroding. “We used to be able to collect a bucket of abalone and sea cucumbers easily, but now there’s hardly any,” Salih explains. “Other high-value fish are also much scarcer. Depending on the sea for a living has become very difficult and extremely challenging.” [Source Rebecca Cairns, CNN, November 22, 2024]

Across Southeast Asia, heavy overexploitation of fish stocks is being compounded by rising sea temperatures and increasing ocean acidity, which are destroying fish habitats. In Malaysia, populations of bottom-dwelling demersal fish have declined by as much as 90 percent in some areas. As a result, growing numbers of Bajau Laut are abandoning their traditional nomadic maritime lifestyle, leaving them more vulnerable to environmental change. In the past, when fishing grounds were depleted, families could simply move elsewhere. Sedentary settlement has reduced this flexibility, tying livelihoods to particular islands or reefs.

According to Adzmin Fatta, program manager at Reef Check Malaysia and co-founder of Green Semporna, coastal communities that depend on the sea are “highly vulnerable” to climate-related impacts such as coral bleaching, sea-level rise, shoreline erosion, and increasingly severe weather events.

Plastic pollution adds yet another strain to an already fragile marine ecosystem, says Robin Philippo, director of the Tropical Research and Conservation Centre (TRACC), which works on reef rehabilitation near Semporna. Discarded water bottles, snack packaging, and flip-flops are now a common sight at sea. While local communities are often blamed, Philippo argues that tourism generates most of this waste, pointing to the mismatch between Semporna’s capacity and the volume of rubbish produced as a key factor in the problem.

For residents like Nukiman, the changes are unmistakable. “It used to be much nicer spending time in the ocean, but now there’s so much trash that it’s no longer enjoyable,” he says. Plastic pollution is especially severe around their village, he adds, because there is no proper waste management system, making it increasingly difficult to gather shellfish in the shallow waters.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025