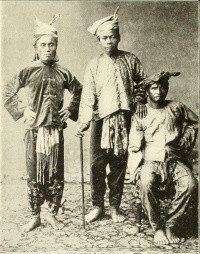

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS

The Sulu Archipelago is home to several indigenous ethnolinguistic groups, most notably the Tausug, various Sama (Samal) communities, the Sama-Bajau, the Yakan, and the Jama Mapun. These groups are predominantly Muslim and were historically united under the Sulu Sultanate, which shaped the region’s political and cultural life for centuries. In addition to its indigenous populations, the archipelago also includes Chinese and northern Filipino migrant communities. Among the native groups, the Tausug are the most politically and culturally dominant, especially on Jolo Island.

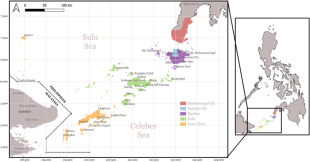

The Sulu Archipelago consists of roughly 400 islands, bordered by the Sulu Sea to the west and the Celebes Sea to the east and south, lying between 4°30 and 6°50 north latitude and 119°10 and 122°25 east longitude. Jolo, the largest island, is rugged and mountainous, measuring about 59 kilometers in length and 16 kilometers in width. Its fertile volcanic soils allow intensive dry-field farming across approximately half of the island, while the remaining areas consist of steep mountains, residual forest, or former farmland now overgrown with imperata grass. Annual rainfall ranges from 178 to 254 centimeters and is generally plentiful, though irregular—especially during the northeast monsoon from November to March. The island is encircled by coral reefs and bordered by sandy beaches and mangrove swamps.

The Tausug primarily inhabit Jolo, Siasi, and Patikul. Their language functions as the regional lingua franca across much of the archipelago. Historically, they were known as skilled maritime traders and formidable warriors, playing a central role in the leadership and expansion of the Sulu Sultanate. The Sama or Samal comprise a diverse set of communities spread across the islands, including both land-based and coastal groups. Closely related to them are the Sama-Bajau (also called Badjao or Bajau), often referred to as “sea nomads.” Traditionally oriented toward the sea, many Sama-Bajau communities lived on boats or in stilt houses built over coastal waters, sustaining themselves through fishing, diving, and maritime trade. The Yakan are native to Basilan Island and are widely recognized for their intricate weaving traditions and distinctive material culture. The Jama Mapun, meanwhile, are primarily concentrated in the Cagayan de Mapun island group. Across the archipelago, the population largely follows Sunni Islam of the Shafi‘i school, which continues to influence social norms, law, and daily life.

The Sangir is a group that lives in the Sanihe and Taluad islands between southern Mindanao and northern Sulawesi. Also known as the Sangirezen and Talaoerezen, they are also found in Mindanao and Indonesia. Most are Christians although some are Muslims. Most have been assimilated into the national culture. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

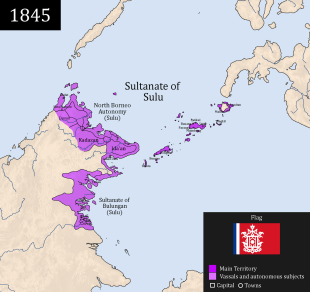

Sulu Sultanate

The Sulu Sultanate was a Sunni Muslim Tausug state that exercised authority over the Sulu Archipelago, coastal parts of southern Mindanao, and sections of Palawan in the Philippines, as well as areas of northeastern Borneo, including parts of modern-day Sabah and North Kalimantan. It grew wealthy from the spice trade, pearling, weapons sales and the slave market. As head of an Islamic polity, the sultan embodied both political and religious authority. Official genealogies traced his lineage to the Prophet Muhammad, and he was expected to exemplify moral virtue and piety. Mirroring the political hierarchy was a religious structure that converged in the person of the sultan and extended downward through the kadi (judge), ulama (scholars), imam, hatib (preacher), and bilal (caller to prayer), who served as legal advisers and mosque officials at various levels of society. [Source: Wikipedia, Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The sultanate was founded either in 1405 or in 1457 by Sharif ul-Hashim, a Johore-born explorer and Sunni religious scholar. Upon establishing rule in Buansa, Sulu, he assumed the regnal name Paduka Mahasari Maulana al-Sultan Sharif ul-Hashim. Under his leadership, the polity consolidated Islamic authority in the region. In 1578, the Sulu Sultanate asserted its independence from the Bruneian Empire. The Sulu Sultanate is possibly referenced in the Javanese epic Kakawin Nagarakretagama, written in 1365, where a polity called Solot is listed among the territories within the Tanjungnagara (Kalimantan–Philippines) region said to fall under the mandala sphere of influence of the Majapahit Empire. Until the mid-nineteenth century, the Sulu Sultanate conducted extensive trade with China in pearls, birds’ nests, trepang (sea cumcumber), camphor, and sandalwood.

At the height of its power, the sultanate’s influence extended from the Zamboanga Peninsula in Mindanao eastward to Palawan in the north. In northeastern Borneo, its domain reportedly stretched from Marudu Bay in Sabah to Tepian in the Sembakung district of North Kalimantan; other accounts include territory reaching as far as Kimanis Bay, overlapping with areas claimed by Brunei. As a maritime thalassocracy, the sultanate derived its strength from sea power and regional trade networks. However, the arrival of Western colonial powers—Spain, Britain, the Netherlands, France, Germany, and later the United States—gradually diminished its sovereignty. Its remaining political authority was formally relinquished in 1915 through the Carpenter Agreement with the United States. A Sultan of Sulu exists today. The position is largely ceremonial and doesn’t have any real political power but is influential among the Tausug.

Political authority within the Sulu Sultanate functioned less as centralized control and more through overlapping, leader-centered alliances that linked local headmen to the sultan at the apex. Authority was expressed through ranked titles, and leaders mediated disputes, enforced laws, provided protection, and administered religious affairs. The sultan’s influence was strongest in the core areas of Jolo and weaker in peripheral regions. He was advised by a state council (ruma bichara) that also played a role in succession.

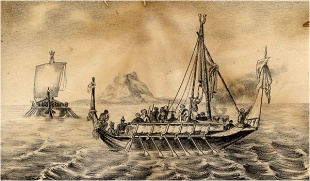

During the Sulu Sultanate period conflict was endemic. Armed feuds were common and typically followed a pattern of individual revenge. At times, a widely ramifying feud resulted in battles involving more than 100 persons on each side. In the past, external warfare took the form of piracy and coastal raiding, organized at the levels of medial and maximal alliance, primarily for slaves and booty. In the nineteenth century, following the establishment of a precarious Spanish military hegemony over Sulu, a pattern of ritual suicide (sabbil) developed as a form of personal jihad, or religious martyrdom.

Tausug

The Tausug is the dominant group in the Sulu Archipelago. Also known as the Joloanos, Jolo Moros, Suluk, Suluk Moros, Sulus and Taw Sug, they are a Muslim seafaring people that once presided over an empire that stretched from the southern Philippines to Borneo. The are the most numerous on the Sulu island of Jolo and are present in large numbers on other Sulu islands and in southern Mindanao. They have traditionally occupied parts of the coastline suitable for agriculture, leaving the low islands and coastlines to the Sama-Bajua (Samal). The Tausug are fairly conservative. Children attend Koranic school and study the Koran with tutors. Even so beliefs in spirits and superstitions endure. Children wear amulets for protection and sick people seek help from folk healers. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Jolo Island, strategically situated near the center of the Sulu Archipelago, serves as the cultural and political heartland of Tausug society. Significant Tausug communities are also found on the islands of Pata, Tapul, Lugus, and Siasi, along the northern and eastern coasts of Basilan, and in the Mindanao provinces of Zamboanga del Sur and Cotabato. Beyond the Philippines, Tausug populations extend into eastern Sabah, Malaysia, from the Labuk-Sugut area south to Tawau. Within Sulu, the Tausug generally inhabit the larger, elevated islands that support intensive agriculture, while the low-lying coral islands are more commonly occupied by the maritime-oriented Samal. Despite their wide distribution, the Tausug remain culturally cohesive, with minimal regional variation. On Jolo, coastal residents identify themselves as Tau Higad (“people of the seacoast”) and refer to inland inhabitants as Tau Gimnba (“people of the hinterland”); both groups call Tausug living outside Jolo Tau Pu (“island people”). In Sabah, the Tausug are officially and ethnographically known as “Suluk.”

The Tausug means "people of the current" (tau, "people"; sug, "sea current"). Their total population is around 1.9–2.2 million, with about 1,615,823 in the Philippines, 209,000–500,000 in Malaysia and 12,000 in Indonesia. By one estimate there were 400,000 Tausug in the 1980s, about half of whom lived on Jolo. In 1970, the Tausug population in the Philippines was estimated at 325,000, with about 190,000 residing on Jolo Island. After the destruction of Jolo town in 1974 during clashes between Muslim separatists and Christian government forces, this number likely declined as many Tausug were displaced, relocating to Basilan, Zamboanga, and Sabah. In Sabah, locally born Tausug numbered approximately 10,900 in 1970. More recent estimates, including refugees, range widely from 20,000 to as many as 100,000.

The Tausug Language belongs to the East Mindanao subgroup of the Central Philippine language family. It is most closely affiliated with Butuanun, which is spoken at the mouth of the Agusan River in northeastern Mindanao. It is believed that the two languages separated around 900 years ago. Tausug also exhibits extensive linguistic convergence with Sama-Bajau, indicating a long and close association. Tausug shows little dialectal variation and historically served as the lingua franca of the Sulu Sultanate. A Malay-Arabic script is used for religious and other writings.

Tausug History

The Tausug appear to have come to the Sulu islands from southern Mindanao and converted to Islam possibly as early as the 11th century. Their sultan was at the peak of his power in the 18th and early 19th century and grew rich largely from trading slaves, many who were Christian Filipinos. The slave trade was ended by the Americans who took over Jolo town in 1899 but were not able to control the island until 1913, and even then only nominally so. Jolo today is at the forefront of the Islamic separatist movement. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Tausug migration to the Sulu Archipelago from northeastern Mindanao was likely as a result of interaction with Sama-Bajau traders. This movement may have begun during the early Sung period and was probably connected to the expansion of Chinese maritime trade under the Sung (960–1279) and Yuan (1280–1368) dynasties. Linguistic evidence indicates that a Tausug-speaking community may have developed from a bilingual population established in Jolo by Sama traders and their Tausug-speaking wives and children between the tenth and eleventh centuries. By the late thirteenth century, the Tausug had emerged as a regionally influential commercial elite within the islands.

The timing of Islam’s earliest arrival in Sulu remains uncertain, but initial contact may have occurred in the late Sung era, when Arab merchants forged direct trade routes to southern China through the Sulu Archipelago. There is also evidence of early missionary activity by Chinese Muslims. Islam later gained renewed momentum through the efforts of Sufi missionaries traveling from Arabia or Iraq by way of Malaya and Sumatra. In the mid-fifteenth century, the Sulu Sultanate was established, traditionally attributed to the figure of Salip (Sharif) Abu Bakkar, also known as Sultan Shariful Hashim. The formation of the sultanate solidified Tausug political dominance and deepened their social and economic distinctions from the Sama-Bajau–speaking Samal.

The sultanate reached its height during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when its influence extended from Sulu across the coastal regions of Mindanao and into northern Borneo. Jolo became a major hub of trade, raiding, and slave commerce, serving as an entrepôt for captives, many taken from Christian areas of the Philippines. Slavery fueled expanded production and regional exchange and was conducted not only by Tausug leaders but also by Iranun and Balangingi Samal raiders operating under Tausug aristocratic patronage.

Following Spain’s colonization of the Philippines in the sixteenth century, warfare between Spanish forces and the Tausug continued almost uninterrupted for three centuries. The first Spanish assault on Jolo occurred in 1578. Although the Spanish briefly occupied the town in the seventeenth century, a permanent garrison was not established until 1876. After Spain’s defeat in the Spanish-American War, American forces occupied Jolo in 1899 but faced strong resistance and did not secure control of the island’s interior until 1913. The subsequent Pax Americana led to the abolition of slavery, the confiscation of firearms, and the temporary suppression of piracy and feuding. In 1915, under the Carpenter Agreement, Sultan Jamal ul-Kiram II renounced all secular authority while retaining his position as a religious leader.

Since World War II, indigenous armed conflicts have resurfaced in the region. Sulu has become a focal point of Islamic separatism and is recognized as the birthplace of several founding leaders of the Moro National Liberation Front, as well as the site of some of the most intense and destructive fighting in recent Philippine history.

Tausug Religion

The Tausug are Sunni Muslims who follow the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence. The Five Pillars of Islam are formally observed, although regular daily prayer is most consistently practiced by the elderly. Misfortune—whether illness, accidents, or other hardships—is ultimately understood as the will of God. At the same time, older layers of belief persist, including the idea that the world is inhabited by local spirits capable of bringing harm or good fortune. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Imam hold a central position in community life, officiating at rites of passage, providing religious guidance, and leading congregational prayers. Religion has long been fundamental to Tausug identity and historically reinforced the hierarchical order of the state. In times of sickness, people may consult folk healers known as mangungubat. These traditional specialists, who are believed to receive their healing power through dreams or apprenticeship under senior curers, rely primarily on herbal medicines accompanied by prayers.

Celebrations: Important observances in the religious calendar include fasting during Ramadan; Hari Raya Puasa (ʿId al-Fitr), the feast marking the end of Ramadan; Hari Raya Hadji (ʿId al-Adha), the Feast of Sacrifice held on the tenth day of Dhu al-Hijjah; Maulideen Nabi, celebrating the Prophet’s birthday on the twelfth of Rabiʿ al-Awwal; and Panulak Balah (“sending away evil”), a ritual bathing ceremony performed on the last Wednesday of Safar.

Death and Funerals: Four essential rites are performed at death: washing the body, shrouding it, reciting the funeral prayer, and burial. A seven-day vigil follows. Depending on a family’s resources, memorial feasts may be held on the 7th, 20th, 40th, and 100th days after death, as well as on the first three anniversaries. It is believed that each person possesses four souls that depart the body at death. The deceased undergoes punishment in hell proportionate to past misdeeds and accumulated merit. On the fifteenth day of Shaʿban, one soul (ro) returns to earth, where prayers are offered and graves are cleaned in remembrance.

Tausug Society and Family

Tausug society was historically divided into three ranked groups: nobles, commoners, and slaves. The nobility included datu, who held inherited political titles, and salip, religious figures claiming descent from the Prophet. Although rank was legally defined, wealth and influence could be achieved outside inherited status, allowing individuals of humble origin to rise in prominence—an arrangement described as “status-conscious egalitarianism.” The Tausug recognized three types of law: Quranic law, interpreted religious law (sara) codified by the sultan and officials, and customary law (adat), which included matters of honor. Today, while formal political structures follow Philippine electoral systems—dividing the region into the provinces of Sulu and Tawi-Tawi—traditional alliance networks and political values remain influential. Though the sultan’s secular authority has declined, he retains important religious functions, and rival claimants have existed since the death of Sultan Jamal ul-Kiram II. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Tausug kinship is based mainly on the bilateral kindred (usbawaris), recognizing both male and female lines and extending to second cousins. Lineal descent groups have little importance, and there are no permanent corporate clans or lineage groups. Although Islamic (Shafi) law formally links children to the father’s kin (usbaq) in matters of marriage and divorce, most other relationships are recognized equally on both the mother’s and father’s sides. Kin relationships are largely personal and one-to-one rather than group-based. Relatives usually act together only during crises—such as illness, urgent need, or threats to family honor. Loyalty among siblings is especially strong, and ties between brothers and first cousins are crucial for building political alliances and gaining support during armed conflict. Kinship terminology emphasizes generation, relative age, and lineality, and cousin terms follow the Eskimo pattern.

Marriages are often arranged or take place through elopement or abduction and involve the payment of bride-wealth. Polygyny is allowed but rare, and divorce is also uncommon. Before marriage, young men and women have limited contact, and women are kept in relative seclusion to preserve their value as political and economic assets. First and second cousins—except the children of brothers—are preferred spouses. Marriage involves detailed negotiations over bride-wealth and expenses, and weddings are held at the groom’s parents’ house, officiated by an imam. Couples usually reside first with the wife’s family, later establishing independent residence, which is the ideal.

The typical household consists of either a nuclear family or a stem family, including parents, unmarried children, and one married child with spouse and children. Fully extended families are rare. Land is usually inherited by sons, often favoring the eldest, while other property is generally divided bilaterally. Child-rearing involves both parents and older siblings. Because infants are believed to be vulnerable, they are protected with amulets (hampan) and temporarily secluded after birth. Children of both sexes undergo hair cutting ceremonies when they are one or two. Boys are circumcised in a garden ceremony (pagislam) when the are in their early teens. In the past and maybe today girls were circumcised (pagsunnat) when they were 5 or 6 without a ceremony and after that were generally kept in seclusion. Children commonly study the Quran and celebrate completion with a public ceremony (pagtammat). Socialization stresses shame, respect for authority, and family honor. Although children attend public schools, at least in the past few completed primary education.

Tausug Villages and Economic Activity

The Tausug are primarily agriculturist who grow a wide variety of starch crops, vegetables and fruit. They live in thatch-roof, timber- or bamboo walled houses about two or three meters off the ground and set close to family fields. Tausug houses are usually raised and surrounded by elevated porches, with a separate kitchen at the rear. Many are enclosed within a protective stockade that surrounds the house compound. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Tausug communities, except in towns and coastal fishing villages, are typically dispersed, with individual houses scattered across the landscape. Households or clusters of two or three households make up many communities. Large villages are organized around a core kin group. Boundaries of villages tend to be ill defined and this has led to feuds, which can be quite nasty, involving battles with a 100 people on each side. Hamlets are called lungan, which are organized into communities (kauman), which have a common name and a headman. The unity of a kauman depends on intermarriage, the presence of a core kin group, shared attendance at a mosque, recent experiences of conflict, and the political skill of its headman.

The Tausug practice plow agriculture, growing dry rice on permanently diked, nonirrigated fields using cattle or water buffalo as draft animals. Rice is intercropped with corn, cassava, millet, sorghum, and sesame. There are three annual harvests: first corn and other cereals, then rice, and finally cassava, which continues to be harvested into the dry season. Fields are typically fallowed every third year. Other crops, planted in separate gardens, include peanuts, yams, eggplants, beans, tomatoes, and onions. Major cash crops include coconuts for copra, coffee, abaca, and fruit such as mangoes, mangosteens, bananas, jackfruits, durians, lanzones, and oranges. Many coastal Tausug are landless and rely on fishing or petty trade. Fishing is conducted in coastal waters using nets, hook-and-line, or traps.

Coconuts and smuggling are major economic activities. In the past coastal raiding and piracy were common forms of employment. Copra and abaca are sold mainly through Chinese wholesalers, while local trade is handled by Tausug or Samal merchants. Smuggling between Sulu and nearby Malaysian ports continues to be an important economic activity and contributes to local differences in wealth and power.

Both men and women share farm work, although men perform heavier tasks such as clearing, plowing, and fencing, while planting, weeding, and harvesting are done jointly. Women tend vegetable gardens and gather fruit. Both sexes engage in trade. Fishing, metalwork, interisland trade, and smuggling are largely male occupations, though women often manage finances in smuggling operations.

Yakan

The Yakan are a Muslim people that live mostly on the island of Basilan south of Mindanao. The total Yakan population is 282,715 according to the 2020 Philippines census. In the early 1990s, the number of Yakan was usually estimated at between 90,000 and 100,000, though variations between 60,000 and 196,000 were found. At that time Yakan constituted about half the population of Basilan. Now they make up less than that. [Source: Inger Wu, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Basilan is located at 6°40' N and 122°00' E. It has a total area of 1,283 square kilometers (495 square miles). It has a tropical climate, with a rainy season from April to October and a dry season from November to April. The interior is mostly mountainous. The Yakan have traditionally lived on the interior of the island, particularly in the east central and southwestern parts, while the Sama-Bajau (Samal) and Tausug, who are so Muslim, live along the coasts. There is also a large Christian population, mostly from the Visayan Islands, who have emigrated there. A few Yakan people live on Sacol Island.

Culturally, the Yakan are closely related to other Muslim groups in the area, known as Moros, particularly the Tausug and Sama-Bajau. Despite strong similarities—especially with the Sama-Bajau—the Yakan maintain a distinct and identifiable culture. The Yakan language is an Austronesian language closely related to the Sama-Bajau language, so much so that some linguists consider it to be Sama-Bajau dialect. Takan musical traditions include percussion instruments used at weddings and rituals, as well as flutes and Jew’s harps. Healing practices combine Islamic prayer by the imam with herbal remedies and spirit-invoking rituals performed by specialists.

Yakan settlements are usually organized around a mosque. Community leadership rests with the imam and a council, while wealth, age, and local influence are respected, though there is little strong social stratification. Although the Yakan are Muslims, women are not segregated and have never been veiled. In the past young women had a lot of freedom to do what they wanted but that is no longer the case. There are two overlapping political systems: a traditional one based on parishes centered on the langgal (mosque) with a council handling local affairs, and the modern governmental structure of the Philippines. Basilan functions as a province with municipalities led by mayors, while barrios—made up of smaller sitios—are headed by barrio captains, who are especially important in local Yakan life. In the past, fighting among Yakan groups was not uncommon, and conflicts still occasionally arise. Disputes are usually mediated by the imam, council, or barrio captain, while serious matters such as killings are brought before official courts. Marriage disputes may be settled locally, though more serious cases can be referred to the sultan.

Yakan History and Religion

The Yakan are believed to be the original inhabitants of Basilan and may once have occupied the entire island. The Sama-Bajau and Tasuag arrived later from the Sulu islands. The Sulu Sultanate claimed Basilan as part of its domain. Christian occupation began in 1842 when the Spanish colonial government built a fort at Isabela on Basilan’s northwest coast and Christian Filipinos established rubber and coconut plantations nearby. In the 1870s, a Christian Tagalog escapee from a penal colony in nearby Mindanao conquered the Yakan. After initial resistance, the Yakan recognized him as their leader with the title of datu. He converted to Islam and worked to limit hostilities between Yakan and Christians. He was succeeded first by his nephew and later by his nephew’s son, who was proclaimed sultan of Basilan in 1969. Unrest in the southern Philippines during the 1970s affected the Yakan severely. In the early part of the decade, rebels controlled much of Basilan, and many Yakan were evacuated for several years. They continue to suffer as a result of Islamic insurgents basing themselves there. [Source: Inger Wu, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Yakan are Muslims but a number of pre-Islamic beliefs remain, including a varieties of ceremonies associated with the rice agricultural cycle and beliefs in spirits and a special devil that attacks people in the second month of the year. To avoid the danger, a bathing ritual is performed on three successive Wednesdays of that month. Graves are marked with a markers that symbolizes a boat which is supposed to take the dead to the afterlife. In recent years Muslim missionaries have visited the Yakan with the aim of teaching them proper Islam.

The langgal (mosque) is the center of Muslim religious practice, where official prayers are conducted. An imam is head of the langgal and has two helpers: the habib and the bilal. The imam leads services in the langgal, which is typically a very basic structure, and officiates life-cycle rituals and rice ceremonies. An important part of his role is leading household prayers, such as asking for recovery in case of sickness or blessing a new house. However, there are other religious practitioners who probably derive from an older, pre-Islamic religion. The most important of these is the Bahasa, a kind of shaman who summons spirits to cure sickness or tell fortunes. The Yakan observe Ramadan and Eid, but their most important holiday is the Prophet Mohammed's birthday in the third Islamic month.

Yakan Family, Marriage and Sex

The most common domestic unit among the Yakan is the nuclear family—husband, wife, and unmarried children—though newly married couples often live temporarily with parents. Children are raised within the family and begin helping with work at an early age, with older siblings caring for younger ones. Single relatives may also join the household. Inheritance is divided equally among children, despite Quranic rules that would grant sons a larger share.

Marriages involve the payment of a bride price to the bride— who must return it after she has had children—and presents, which she gets to keep. Wedding expenses are covered by the groom’s family. While polygyny is permitted under Islam, most Yakan men have only one wife, and multiple marriages are increasingly rare. Marriages were once arranged, but parents now often consider their children’s preferences. Couples usually live first with either set of parents before establishing their own household. Divorce is fairly common and may be initiated by either spouse, though the bride-price must be returned if the wife seeks the divorce.

Descent is bilateral, with equal recognition of both the father’s and mother’s kin. Strong solidarity exists among relatives, who gather for major events such as weddings and funerals. Kinship terminology does not distinguish between maternal and paternal relatives, though sibling terms differentiate between older and younger siblings.

The Yakan observe some unusual honeymoon rituals. Before the couple’s first night together, each is bathed separately so that future children will be born and remain clean. The groom is also taken to the river for a ritual bath before the wedding ceremony begins. The first kiss should be planted on the forehead for oneness of mind, with eyes opened so that his children will not be born blind. He should breathe lightly so that later in life he will have fewer problems. [Source: kasal.com ^^]

Before their first sexual intercourse, the bride makes sure that she is accepted as a wife and not as a whore by asking questions about her status. The groom has to answer adequately that she is his wife. Just before the sexual act, the groom should first step on the right foot as heavily as he can. This symbolizes strength. The first hand to touch his wife should be the right one, for strength and long life.

The bride wants to be assured that her marriage is accepted spiritually and that she will be his wife even after life. For this reason, the bedding items have to be sanctified and be named in a liturgical language. Permission is also granted to the groom to own the body of his wife and also name her anatomical parts in liturgical speech. Any sexual intercourse that is not done according to the natural way is strongly condemned by the Yakan and will bring punishment from God not only on the the perpetrarors and their families. ^^

Yakan Houses, Villages and Economic Activity

Yakan live in rectangular pile houses with thatch or corrugated metal roofs set up in middle of fields, with vegetables patches and fruit trees around the house. The houses are often widely scattered to the point it is difficult to figure out where one village ends and another begins. The walls of the houses are typically made of plaited reed, bamboo, or wooden boards, and the floor is usually made of bamboo or timber. The house usually has only one big room with no separate quarters for women. A kitchen is joined to the house. The house is entered through a porch, an important part of the structure. The inhabitants of a settlement may or may not be related. In recent decades some changes have recently taken place. Though houses may still be scattered, this is no longer the case everywhere as spaces has become less plentiful. Now, some people build closer to one another, which was rarely done before and only when the occupants of the houses were closely related. Additionally, those who can afford it now build better, more modern houses. [Source: Inger Wu, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Yakan are primarily farmers who raise dry rice and a variety of vegetables and fruit and keep water buffalo as plow animals. Coconuts are an important cash crop. The Yakan primarily cultivate upland rice, harvested once a year, along with sweet potato and cassava. Other crops include maize, beans, eggplants, yams, coffee, sugarcane, and fruits such as banana, mango, and durian. Fields are farmed in rotation: rice is followed by root crops, then left fallow before replanting. Most produce is for household use, and rice supplies are often insufficient between harvests. Land is individually owned, though formal legal titles were rare until recently, leading to disputes with outsiders; increasing numbers of Yakan now secure legal ownership.

Coconuts are grown for copra, sometimes replacing rice as the dominant crop. The Yakan keep few domestic animals today—mainly cows, water buffalo, goats, and chickens—and do not raise pigs. Hunting has declined, and fish, though important in the diet, are usually purchased from the Sama-Bajau rather than caught. Agricultural labor is shared by men and women, though coconut and copra work and smithing is mainly done by men while weaving is done by women. Weaving is the most significant craft, with women producing traditional textiles on backstrap looms for both personal use and sale. Some men work as smiths or boat builders, though the Yakan are not primarily seafaring. Trade now relies on money rather than barter, and goods are sold in markets or small local stores.

Sama-Bajau Sea People

The term Sama-Bajau is used to describe a diverse group of Sama-Bajau-speaking people who are found in a large maritime area with many islands that stretch from central Philippines to the eastern coast of Borneo and from Sulawesi to Roti in eastern Indonesia. The Sama-Bajau people usually call themselves the Sama or Samah (formally A'a Sama, "Sama people") and have traditionally been known by outsiders as Bajau (also spelled Badjao, Bajaw, Badjau, Badjaw, Bajo or Bayao). They have also been Sea Gypsies, Sea Nomads and Samal as well as Sama Moro and Turijene in the Philippines, Luwa’an, Pala’au, Sama Dilaut and Turijene in Indonesia, and the Bajau Laut in Malaysia. Some of these names refer to Sama-Bajua subgroups. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Most Sama-Bajau are Muslims. In the Philippines, they are grouped with the Moro people, who have similar religious beliefs. For most of their history, the Sama-Bajau have been nomadic seafaring people who live off the sea through trade and subsistence fishing. They have traditionally stayed close to shore with houses on stilts and traveled, and sometimes lived in, handmade boats lepa. Sama-Bajau are the dominant ethnic group in Tawi-Tawi islands and are generally associated with the Sulu islands, the southernmost islands of the Philippines. They are also found in the coastal areas of Mindanao and other islands in the southern Philippines, as well as in northern and eastern Borneo, Sulawesi, and throughout the eastern Indonesian islands.

Sama-Bajau speakers are probably the most widely dispersed indigenous ethnolinguistic group in Southeast Asia. Their settlements are scattered throughout the central Philippines, the Sulu Archipelago, the eastern coast of Borneo, Palawan, western Sabah (Malaysia), and coastal Sulawesi. They also have small enclaves in Zambales and northern Mindanao. In the Philippines, most Sama speakers are referred to as "Samal," a Tausug term also used by Christian Filipinos, with the exceptions of Yakan, Abak, and Jama Mapun. In Indonesia and Malaysia, related Sama-speaking groups are known as "Bajau," a term of apparent Malay origin. In the Philippines, however, the term "Bajau" is more narrowly reserved for boat-nomadic or formerly nomadic groups referred to elsewhere as "Bajau Laut" or "Orang Laut."

RELATED ARTICLES:

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026