MUSLIMS THE PHILIPPINES

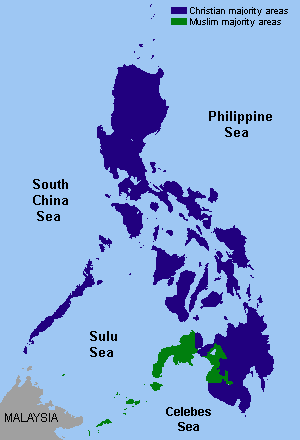

Where Muslims live the Philippines: Muslims ins green; Christians in blue

Muslims, who make about 5 percent of the total population, are the most significant minority in the Philippines. Although undifferentiated racially from other Filipinos, they for the most part remain outside the mainstream of national life, set apart by their religion and way of life. In the 1970s, in reaction to consolidation of central government power under martial law, which began in 1972, the Muslim Filipino, or Moro population increasingly identified with the worldwide Islamic community, particularly in Malaysia, Indonesia, Libya, and Middle Eastern countries. Longstanding economic grievances stemming from years of governmental neglect and from resentment of popular prejudice against them contributed to the roots of Muslim insurgency. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Muslim Filipinos traditionally have not been a closely knit or even allied group. They were fiercely proud of their separate identities, and conflict between them was endemic for centuries. In addition to being divided by different languages and political structures, the separate groups also differed in their degree of Islamic orthodoxy. For example, the Tausugs, the first group to adopt Islam, criticized the more recently Islamicized Yakan and Bajau peoples for being less zealous in observing Islamic tenets and practices. Internal differences among Moros in the 1980s, however, were outweighed by commonalities of historical experience vis-à-vis non-Muslims and by shared cultural, social, and legal traditions. *

Most Muslim Filipinos live on Mindanao, the second largest island in the Philippines after Luzon and southernmost major island of archipelago. Ravaged for years by violence from Muslim insurgencies, it has opened more to tourism in recent years as peace treaties with rebel groups have been negotiated and signed. Of the 20 million or so resident of Mindanao, about 7 million are Muslims. Still largely undisturbed and unspoiled, it features wild tropical rain forests, stone-age tribes, high mountains and beaches and towns still used by pirates. Mindanao has rich volcanic soil, dense forests that are the home of monkey-eating eagles and other rare animals and rich deposits of gold, copper, nickel and other precious metals. Many people are peasant farmers or employees on large pineapple and coconut plantations. The highest mountain in the Philippines is Mt. Apo, a dormant volcano found in Mindanao, at 2,954 meters (9,689 feet). Principal rivers on Mindanao include the Mindanao River (known as the Pulangi River in its upper reaches), and the Agusan. The Philippines cultured pearl industry is centered in Mindanao. Tuna fishing is big in the General Santos area.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Moros

The Muslim ethnic groups of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan are collectively referred to as the Moro people, a broad category that includes some indigenous people groups and some non-Indigenous people groups. Filipino Muslims in general are called Moros. With a population of over 5 million people, they comprise about 5 percent of the country's total population. Traditionally-Muslim minorities from Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are indigenous peoples or not.[Source: Wikipedia]

The term Moros comes from the Spanish. Moros is Spanish for Moors, the term the Spaniards used to describe the Muslims in Morocco. The Spanish fought the Moors from North Africa in the Middle Ages. The Moors even occupied southern Spain for a time. The Moros of the Philippines are close kin of the Muslims in Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. They have traditionally been a fierce, independent, seafaring people who have resisted the Spanish, Americans and the Philippines government. The traditional Muslim outfit worn by women is Malay in origin and consists of a gathered wrap-over or sarong type of ankle-length skirt, long-sleeve jacket.

Moros are confined almost entirely to the southern part of the country — southern and western Mindanao, southern Palawan, and the Sulu Archipelago. Ten subgroups can be identified on the basis of language. Three of these groups make up the great majority of Moros. They are the Maguindanaos of North Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, and Maguindanao provinces; the Maranaos of the two Lanao provinces; and the Tausugs, principally from Jolo Island. Smaller groups are the Samals and Bajaus, principally of the Sulu Archipelago; the Yakans of Zamboanga del Sur Province; the Ilanons and Sangirs of Southern Mindanao Region; the Melabugnans of southern Palawan; and the Jama Mapuns of the tiny Cagayan Islands. [Source: Library of Congress]

Moro Society

The traditional structure of Moro society focused on a sultan who was both a secular and a religious leader and whose authority was sanctioned by the Quran. The datu were communal leaders who measured power not by their holdings in landed wealth but by the numbers of their followers. In return for tribute and labor, the datu provided aid in emergencies and advocacy in disputes with followers of another chief. Thus, through his agama (court — actually an informal dispute-settling session), a datu became basic to the smooth function of Moro society. He was a powerful authority figure who might have as many as four wives and who might enslave other Muslims in raids on their villages or in debt bondage. He might also demand revenge (maratabat) for the death of a follower or upon injury to his pride or honor. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The datu continued to play a central role in Moro society in the 1980s. In many parts of Muslim Mindanao, they still administered the sharia (sacred Islamic law) through the agama. They could no longer expand their circle of followers by raiding other villages, but they achieved the same end by accumulating wealth and then using it to provide aid, employment, and protection for less fortunate neighbors. Datu support was essential for government programs in a Muslim barangay. Although a datu in modern times rarely had more than one wife, polygamy was permitted so long as his wealth was sufficient to provide for more than one. Moro society was still basically hierarchical and familial, at least in rural areas. *

Philippine Government Policy in Mindanao

The national government policies instituted immediately after independence in 1946 abolished the Bureau for Non-Christian Tribes used by the United States to deal with minorities and encouraged migration of Filipinos from densely settled areas such as Central Luzon to the "open" frontier of Mindanao. By the l950s, hundreds of thousands of Ilongos, Ilocanos, Tagalogs, and others were settling in North Cotabato and South Cotabato and Lanao del Norte and Lanao del Sur provinces, where their influx inflamed Moro hostility. The crux of the problem lay in land disputes. Christian migrants to the Cotabatos, for example, complained that they bought land from one Muslim only to have his relatives refuse to recognize the sale and demand more money. Muslims claimed that Christians would title land through government agencies unknown to Muslim residents, for whom land titling was a new institution. Distrust and resentment spread to the public school system, regarded by most Muslims as an agency for the propagation of Christian teachings. By 1970, a terrorist organization of Christians called the Ilagas (Rats) began operating in the Cotabatos, and Muslim armed bands, called Blackshirts, appeared in response. The same thing happened in the Lanaos, where the Muslim Barracudas began fighting the Ilagas. Philippine army troops sent in to restore peace and order were accused by Muslims of siding with the Christians. When martial law was declared in 1972, Muslim Mindanao was in turmoil. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Philippine government discovered shortly after independence that there was a need for some kind of specialized agency to deal with the Muslim minority and so set up the Commission for National Integration in 1957, which was later replaced by the Office of Muslim Affairs and Cultural Communities. Filipino nationalists envisioned a united country in which Christians and Muslims would be offered economic advantages and the Muslims would be assimilated into the dominant culture. They would simply be Filipinos who had their own mode of worship and who refused to eat pork. This vision, less than ideal to many Christians, was generally rejected by Muslims who feared that it was a euphemistic equivalent of assimilation. Concessions were made to Muslim religion and customs. Muslims were exempted from Philippine laws prohibiting polygamy and divorce, and in 1977 the government attempted to codify Muslim law on personal relationships and to harmonize Muslim customary law with Philippine law. A significant break from past practice was the 1990 establishment of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, which gave Muslims in the region control over some aspects of government, but not over national security and foreign affairs. *

There were social factors in the early 1990s that militated against the cultural autonomy sought by Muslim leaders. Industrial development and increased migration outside the region brought new educational demands and new roles for women. These changes in turn led to greater assimilation and, in some cases, even intermarriage. Nevertheless, Muslims and Christians generally remained distinct societies often at odds with one another. *

Islam in the Philippines

In the early 1990s, Filipino Muslims were firmly rooted in their Islamic faith. Every year many went on the hajj (pilgrimage) to the holy city of Mecca; on return men would be addressed by the honoritic "hajj" and women the honorific "hajji". In most Muslim communities, there was at least one mosque from which the muezzin called the faithful to prayer five times a day. Those who responded to the call to public prayer removed their shoes before entering the mosque, aligned themselves in straight rows before the minrab (niche), and offered prayers in the direction of Mecca. An imam, or prayer leader, led the recitation in Arabic verses from the Quran, following the practices of the Sunni sect of Islam common to most of the Muslim world. It was sometimes said that the Moros often neglected to perform the ritual prayer and did not strictly abide by the fast (no food or drink in daylight hours) during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Muslim calendar, or perform the duty of almsgiving. They did, however, scrupulously observe other rituals and practices and celebrate great festivals of Islam such as the end of Ramadan; Muhammad's birthday; the night of his ascension to heaven; and the start of the Muslim New Year, the first day of the month of Muharram. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Islam in the Philippines has absorbed indigenous elements, much as has Catholicism. Moros thus make offerings to spirits (diwatas), malevolent or benign, believing that such spirits can and will have an effect on one's health, family, and crops. They also include pre-Islamic customs in ceremonies marking rites of passage — birth, marriage, and death. Moros share the essentials of Islam, but specific practices vary from one Moro group to another. Although Muslim Filipino women are required to stay at the back of the mosque for prayers (out of the sight of men), they are much freer in daily life than are women in many other Islamic societies. *

Because of the world resurgence of Islam since World War II, Muslims in the Philippines have a stronger sense of their unity as a religious community than they had in the past. Since the early 1970s, more Muslim teachers have visited the nation and more Philippine Muslims have gone abroad — either on the hajj or on scholarships — to Islamic centers than ever before. They have returned revitalized in their faith and determined to strengthen the ties of their fellow Moros with the international Islamic community. As a result, Muslims have built many new mosques and religious schools, where students (male and female) learn the basic rituals and principles of Islam and learn to read the Quran in Arabic. A number of Muslim institutions of higher learning, such as the Jamiatul Philippine al-Islamia in Marawi, also offer advanced courses in Islamic studies. *

Divisions along generational lines have emerged among Moros since the 1960s. Many young Muslims, dissatisfied with the old leaders, asserted that datu and sultans were unnecessary in modern Islamic society. Among themselves, these young reformers were divided between moderates, working within the system for their political goals, and militants, engaging in guerrilla-style warfare. To some degree, the government managed to isolate the militants, but Muslim reformers, whether moderates or militants, were united in their strong religious adherence. This bond was significant, because the Moros felt threatened by the continued expansion of Christians into southern Mindanao and by the prolonged presence of Philippine army troops in their homeland. *

Muslim Schools and Economic Issues

Some Muslim children attend Islamic schools called “madaris” (plural of madrasah). These schools stress the study of the Koran and Arabic and some offer military style training but as a rule they are regarded as more moderate that their counterparts in some parts of Indonesia and Pakistan. There are not that many of them. The alternative is poorly funded public schools. In many case which every school they attend, young people find there are few jobs waiting for them when they graduate.

The government is trying to cooperate with the madaris based on the belief that it is better to work with them rather than let them fall under the influence of Muslim extremists and get support for Saudi Arabia, which supports the rigid Wahabi form of Islam and funds many madrassas in other countries.

Many feel that the problems with Muslim groups in Mindanao are more economic than cultural and religious. Sixteen of the poorest 24 provinces in the Philippines are in Mindanao. An effort was made to improve the lives of people in Mindanao in the 1990s as part of the peace agreement of 1996. Highways were built. Money was poured into airports and ports. New industries were launched. Ferries began operating between Mindanao and Malaysia and Indonesia. Particularly successful was the return and development of the tuna industry in General Santos. See Fishing.

But a lot of the progress came to an end with the Asian economic crisis in 1997-98 when funds for development dried up and an ill-timed offensive by the Joseph Estrada government that involved in attacks on Muslim groups such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) that were involved in development projects such as banana and fruit plantations.

The areas occupied by Muslims often also have large Catholic populations. Some progress has been achieved by “yuplims” (young Muslim professionals).

Discrimination Against Muslims in the Philippines

Muslims have long complained they have been discriminated against. A leader of an a militant group told Newsweek, “We are second-class citizens. There is no Muslim senator, there is no Muslim cabinet minister, there is no Muslim in the Supreme Court.

Muslims who generally live on Mindanao and other islands in the southern Philippines are generally poorer and less educated than other Filipinos. In the Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao the average per capita income in the 1990s was around $350, one third of the national average and less than half the Mindanao average of $800.

Muslims complain that Christians are given preferences for jobs. One former insurgent told the Los Angeles Times, “My son is a licensed engineer, but when the employers look at his resume and see that he is Muslim, they just tell him to come back later. Two years later he still hasn’t found anything, while less deserving Christians managed to land jobs.”

In some Muslim neighborhoods in Zamboanga unemployment rates approach 90 percent. One elderly woman there told the Los Angeles Times, “I have 14 children and 33 grandchildren. Only four of them have jobs, and they are living abroad.

Christian View on the Muslim Groups

Most Catholics are not very sympathetic to the Muslim cause and have been outraged by the killings and kidnapings carried out by militant Muslim groups. A number of priests and teachers have been among those who were murdered. One Catholic resident of Zamboanga told the Asahi Shimbum, “Muslims are trouble. I can tell they hate Christians.”

Many Christian Filipinos view Muslims as violent, warlike and backward. One priest told Newsweek. “The Muslims’ basic motivation has been money. But they have another one—to force everyone in the area to follow the ways of Islam. They’re obsessed by the [idea] that it is their territory.”

The conflict is also a drain on scarce government resources. Manila spends $2.5 million a day to support troops in Mindanao and has lost millions more in lost tax revenues.

Blood Feuds in Mindanao

Blood feuds persist in Muslim Mindanao, in the southern Philippines. Longstanding blood feuds are known as "rido." Studies funded by the Asia Foundation and the U.S. Agency for International Development found there had been more than 1,200 clan feuds in the south since the 1930s. According to AFP: Muslim clans in the southern Philippines are well known for waging prolonged feuds, typically over land, political power or influence. They often use armed followers to attack each other. Such feuds claimed more than 5,500 lives and displaced thousands between the 1930s to 2005, according to the Asia Foundation. During such feuds, the government including the military, typically tries to negotiate for peace between rival sides rather than move to apprehend the contending parties. [Source: AFP, July 12, 2013]

Simone Orendain wrote in PRI, “What rido is, why and how it happens is not the easiest thing to explain. On one level it looks like a relatively simple Hatfields versus McCoys type of feud. But on another level it's more like gang warfare. Take Fatmawati Salapuddin's example. She has spent countless hours mediating between clans enmeshed in ridos. In the 1990's in Salapuddin's hometown in western Mindanao, her father's family and her mother's nephew fought over the same piece of lucrative farm land — with landmines, mortar shells and other weapons. "There were about 20 people killed on each side. They were already firing bombardment mortar, shelling, to the other side," Salapuddin said. [Source: Simone Orendain, PRI, July 25, 2011 /~/]

“In Muslim Mindanao, family squabbles like these can easily escalate into mini-wars, because of the sheer number of people involved. First of all "families" here aren't just mom, dad and the kids. They are clans made up of hundreds of parents, children, brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles and grandparents. Salapuddin said deadly fights can erupt over power, disputed land, or simply trying to preserve someone's "good name." "It's a terrible thing because people get killed, people get displaced, properties are burned, you know," she said. /~/

“And like many seemingly senseless conflicts, ridos can last for generations. "If the clans say, 'we need to fight this group so we're not vulnerable to predation,' family members and clan members, will join in that fight," said Francisco Lara, an anthropologist who studies the phenomenon in Mindanao and schedules meetings with peace workers during hurried lunches in Manila. "Able-bodied men from a very young age will be trained in the process of involvement in clan wars." What's more, some clan members belong to Muslim separatist groups or private militias, which mean they have easy access to weapons. /~/

“Lara said part of the reason that ridos persist is cultural. Well before the Philippines became a country, Muslims in Mindanao had something similar to a feudal system. And as in any feudal structure, power struggles are inevitable. "Mindanao has never really been part of the fold, so called, of the country, of the archipelago. Definitely represents something that is part of the old," Lara said. Another problem is geography. Because the region is far from the seat of power, governments have been unwilling, or unable, to provide support. Instead, he said, Spanish colonizers in the 1500's and Americans in the late 1800's co-opted leaders of elite families to keep order, plying them with money and political power. "The government has not even been able to extend its administrative reach, so in those areas only the clans can provide protection, only clans can provide welfare to local community members," Lara said. /~/

“Peace workers say constituents don't see any perks from the deals with the government, so basic needs like school upkeep and infrastructure go unfunded. Plus, jobs are scarce. They say constituents would just as soon pick up a gun to survive in this type of environment, helping Rido to flourish. And, they say, from the outside, parts of the region look like the "wild, wild west." At a café in Manila, Mussolini Lidasan assesses the situation in his western Mindanao province. He said plain old ignorance is a big culprit in rido. He said it's reaching a point where they can't see beyond the next personal affront or the next power-grab. And Lidasan said it's time the government stepped in directly to help. /~/

"As long as injustices are there, as long as our people are illiterate they have no access to education and as long as there are no clear government programs to uplift their socio-economic conditions," Lidasan said, "then this will go on, on and on and on." It may be hard, though, to change the culture, either of rido or the government itself. Many say that clan leaders have become akin to mob bosses. And like organized crime leaders, they get involved in politics, delivering votes for national politicians, allegedly reaping financial perks for their efforts.” /~/

See Separate Article FAMILIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: GODPARENTS, KINSHIP STRUCTURE AND BLOOD FEUDS Under People

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026