LUMAD ETHNIC GROUPS OF MINDANAO

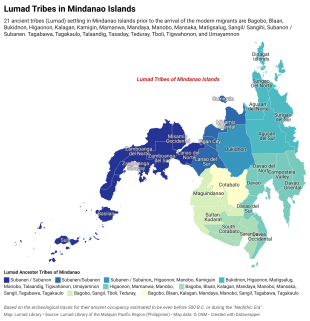

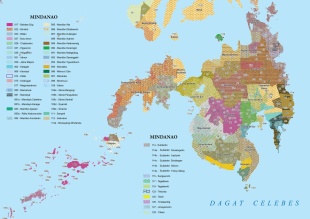

Mindanao, Philippines, is highly diverse, featuring three main cultural groupings: A) the 18+ indigenous Lumad tribes such as the Manobo, Bagobo and Tiboli; B) the 13+ Moro (Muslim) ethno-linguistic groups such as the Maranao, Maguindanao and Tausug), and C) significant Christian settler populations primarily of Visayan descent. Lumad, meaning "native," inhabit the interior highlands, while Moro groups are concentrated in western Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.

The settler and migrant populations — mainly Christians from Visayas (islands between Luzon and Mindanao — mostly arrived in the 20th-century as part of government-sponsored migration programs. They are most heavily concentrated in coastal regions and cities. These communities are distinguished by their diverse languages, traditions, and ancestral domains. In the early 2000s, around 25.8 percent of the population in Mindanao classified themselves as Cebuanos. Other ethnic groups included Bisaya/Binisaya (18.4 percent), Hiligaynon/Ilonggo (8.2 percent), Maguindanaon (5.5 percent), and Maranao (5.4 percent). The remaining 36.6 percent belonged to other ethnic groups.

The 18 major Lumad groups include the Manobo, Bagobo, Banwaon, Blaan, Bukidnon, Dibabawon, Higaonon, Mamanwa, Mandaya, Mangguwangan, Manobo, Mansaka, Matigsalog, Subanen, Tagakaolo, Tiboli, Teduray, and Ubo. Among the most important Lumad groups on Mindanao are 1) the Manobos (a general name for many tribal groups in southern Bukidnon and Agusan del Sur provinces); 2) the Bukidnons of Bukidnon Province; and the 3) Blaans, Tirurays, and T-Bolis of the area of the Cotabato provinces. Among the most important highland Lumad groups on Mindanao are 1) the Bagobos, Mandayas, Atas, and Mansakas, who inhabited mountains bordering the Davao Gulf; 2) the Subanens of upland areas in the Zamboanga provinces; and 3) Mamanuas of the Agusan-Surigao border region. [Source: Library of Congress *]

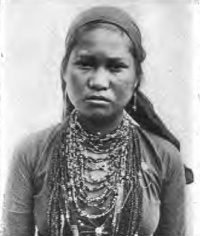

Mindanao tribes were renowned for their elaborate embroidery, appliqué, and bead work. According to Philippines.hvu.nl: “Most characteristic of these 'indigenous groups' is that they live in a traditional way, comparable with how the ancestors lived centuries ago. They distinguish themselves by their language and culture. The cultural heritage is visible in their clothes and ornaments they wear. Housing, economic activities, cultural habits and often religion are all very traditional. Some groups learned to know tourism as a good alternative to earn extra money. In general however, the indigenous groups still live like in the past. [Source: Philippines.hvu.nl]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Mamanwa

The Mamanwa people are one of the oldest tribes in the Philippines. Also spelled and known as Mamanoa, Conking, Mamaw, Amamanusa, Manmanua and Mamaua, they were previously believed to be a subgroup of the Luzon Negritos, but after numerous physical anthropological studies, they are now believed to be distinct from them. They live in Agusan del Norte, Surigao del Norte and Surigao del Sur provinces in northeastern Mindanao and Panaoan Island and Southern Leyte. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Mamanwa Negrito population in the late 2020s was 9,900. According to Wikipedia there were approximately 5,000 speakers of the Mamanwa language in 1990.[Source: Joshua Project, Ethnic Groups of Philippines, California State University, East Bay]

Physically, the Mamanwa share traits common among Negrito peoples, including dark skin, small stature, curly hair, and black eyes. Most are small, standing between 1.35 and 1.5 meters tall. The name Mamanwa comes from the words man, meaning “first,” and banwa, meaning “forest,” together translated as “first forest dwellers.” Before the Mamanwa settled in central Samar Island, an earlier Negrito group known as the Samar Agta is believed to have lived there. With the arrival of the Mamanwa, the Samar Agta reportedly shifted to speaking Waray-Waray, or Northern Samarenyo, and may have partially integrated with the Mamanwa community.

Like other Negrito groups, the Mamanwa adopted the language of a nearby dominant population. They are found mainly in the areas of Kitcharao and Santiago, though they remain highly mobile and frequently relocate. As hunting has declined in importance, traditional tools such as the bow and arrow have largely fallen out of use. The Mamanwa now obtain part of their subsistence through labor arrangements with neighboring groups. Their settlements typically consist of three to twenty households arranged in a circular pattern on high ridges or in valleys, with houses that generally lack walls. Communities are organized around kinship, and leadership is usually held by the oldest and most respected male.

See Separate Article: NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Manobo

The Manobo—also spelled Manobò, Manuvù, Menuvù, or Minuvù—are one of the largest and most diverse indigenous groups in Mindanao, Philippines. Their ancestral lands extend across much of the island, from Sarangani Island to mainland provinces such as Agusan, Davao, Bukidnon, Surigao, Misamis, and Cotabato. Because of their wide geographic spread and linguistic diversity, they are considered the most internally varied among the country’s indigenous peoples. According to the 2020 Census of Population and Housing, approximately 644,904 individuals identified as Manobo. [Source: Wikipedia]

The term “Manobo” is a hispanicized form of Manuvu (also spelled Menuvu or Minuvu), an endonym that simply means “person” or “people.” It may derive from the root word tuvu, meaning “to grow” or “growth,” suggesting the sense of “native-grown” or “indigenous.” Over time, Spanish spelling conventions transformed Manuvu into Manobo, the name more widely used today.

Due to their linguistic and cultural diversity, the Manobo are divided into numerous subgroups. The National Commission on Culture and the Arts has proposed a tentative classification, though it acknowledges that subgroup boundaries are not always clearly defined and may shift depending on linguistic or cultural perspectives.

Major subgroup clusters include:

1) The Ata subgroup, which includes the Dugbatang, Talaingod, and Tagauanum.

2) The Bagobo subgroup, composed of the Attaw (including the Jangan, Klata, Obo, Giangan, and Guiangan), Eto (Ata), Kailawan (Kaylawan), Langilan, Manuvu/Obo, Matigsalug (also spelled Matigsaug or Matig Salug), Tagaluro, and Tigdapaya.

3) The Higaonon subgroup, found in Agusan, Lanao, and Misamis.

4) In Cotabato, the Ilianen, Livunganen, and Pulenyan groups.

5) In South Cotabato, the Cotabato Manobo (including the Tasaday and Blit subgroups), Sarangani, and Tagabawa.

6) In Western Bukidnon, the Kiriyeteka, Ilentungen, and Pulangiyen.

7) Other related groups include those in Agusan del Sur, the Banwaon, and various communities in Bukidnon, among others.

Population estimates have varied over time. While the 2020 census recorded over 644,000 Manobo, earlier estimates ranged from about 250,000 in 1988 to more than 700,000 in the 1990s. Differences in classification, shifting subgroup identities, and geographic dispersion contribute to these variations.

Genetically, the Manobo are primarily of Austronesian ancestry, similar to most Filipino ethnolinguistic groups that trace their origins to the Austronesian expansion. Studies also indicate significant Austroasiatic ancestry, suggesting additional migration influences from Mainland Southeast Asia. Like some other indigenous Philippine groups, including the Mamanwa and the Sama-Bajau, the Manobo also show evidence of Denisovan genetic admixture.

The Cotabato Manabo is a group that has traditionally lived in the southwest highlands of Mindanao. Also known as the Manabo, Ato Manabo Dulangan and Tudag, they are mostly Christians and have been largely assimilated and their traditional culture has disappeared. In the old days in Northern Cotabato, after Manobo boys and girls filed and blackened their teeth, they underwent a ceremony of tasting new rice which qualifies them for admission into full manhood and womanhood. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993), Teresita R. Infante, [Source: kasal.com]

Bagobo

The Bagobos are a group that live in a very mountainous region of Mindanao between the upper Pilangi and Davao rivers. Also known as the Manobo, Manuvu, Obbo and Obo, they are divided into two main groups: the coastal Bagobo who were influenced by Christianity, plantations and were largely assimilated; and upland Bagobo, who traditionally practiced slash and burn agriculture and derived about 25 percent of their food from hunting, gathering and fishing. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

According to the Christian group Joshua there were 69,000 Tagabawa Bagobo and 105,000 Giangan Bagobo in the early 2020s. Most practice traditional animist religions. About 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with 5 to 10 percent of Tagabawa Bagobo and 10 to 50 percent of Giangan Bagobo being Protestant Evangelicals. The Bagobo traditionally believed in spirits who inhabit a sky world and demons who bring sickness and death to incestuous couples. Their villages and have traditionally been grouped into districts led by chiefs called “datu”.

Some upland Bagobo villages are very small and consist of only a few families living on a hill top. Others are larger. Bagobo culture is characterized by strict incest prohibitions, the formation of vengeance groups and the production of long epic poems called “tuwaang”. Bagobo youth used to follow the same beautifying treatment as the Mandayas. Once their teeth were properly filed and blackened, a young man or woman were deemed ready to enter the society of older people.

The Upland Bagobo population was 30,000 in 1962. They have traditionally been organized into bilateral kin groups that work together to pay bridewealth and form vengeance groups. Residence after marriage is usually with the bride’s community. Until World War II, the villages were autonomous and governed by one or more datus. These datus were wealthy legal authorities and negotiators. After World War II, however, a single datu gained control over the entire area in response to intrusions by loggers and Christian Filipinos. ~

Blaan

The Blaan is a group that lives in south-central Mindanao. Also known as the Bilaan, B’laan, Balud, Baraan, Bilanes, Biraan, Blann, Buluan, Buluanes, Tagalagad, Takogan, Tumanao, Vilanes, they live in houses scattered among gardens and are also ruled by datu. The Blaan people of Mindanao wrap their dead inside tree barks. Being enveloped as such, the dead person's body is then suspended from treetops. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993), thefuneralsource.org]

The Blaans speak their native language also known as Blaan, Man can also speak Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Tagalog and, to some extent, Ilocano based on their association with settlers from Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, Negros, Panay and Tagalog- and Ilocano-speaking regions in Luzon. The Blaan name may be derived from "bla", meaning "opponent", and the "people"-denoting suffix "an". According to a 2021 genetic study, the Blaan people also have Papuan admixture.

The total Blaan population according to the 2020 Philippines census is 373,392. According to the Christian group Joshua Project in the early 2020s the Sarangani Blaan numbered 140,000 , the Davao Blaan numbered 63,000 and the Koronadal Blaan numbered 135,000. About 90 percent of Sarangani Blaan are Christian, with 10 to 50 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. Most Davao Blaan and Koronadal Blaan practice traditional animist religions. About 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with many being Protestant Evangelicals.

The Blaan are neighbors of the Tboli and primarily inhabit areas around Lake Sebu and the municipality of Tboli in South Cotabato, as well as parts of Sarangani, General Santos City, southeastern Davao, and the vicinity of Lake Buluan in Cotabato. They are well known for their craftsmanship, particularly in brasswork, beadwork, and the weaving of tabih cloth. Traditional attire is vibrant and richly embroidered, often adorned with intricate bead accessories. Blaan women are especially noted for wearing heavy brass belts decorated with dangling tassels that end in small bells, which softly announce their presence as they walk.

In some communities near the foothills of Mount Matutum, particularly in Sitio 8, Barangay Kinilis, Polomolok, certain Blaan families are involved in producing wild civet coffee. They collect and process the droppings of the Philippine palm civet, from which the specialty coffee is made, making the village locally known for this product.

The Blaan have a rich spiritual tradition centered on a pantheon of deities and nature spirits. Melu is regarded as the supreme being and creator, described as having white skin and golden teeth, and assisted by Fiuwe and Tasu Weh. Sawe joined Melu in dwelling in the world, while Fiuwe and the spirit Diwata reside in the sky. Tasu Weh is considered an evil spirit. Other spiritual beings include Fon Kayoo, the spirit of the trees; Fon Eel, the spirit of water; Fon Batoo, the spirit of rocks and stones; and Tau Dilam Tana, who inhabits the underworld. Among the most feared is Loos Klagan, whose very name is believed to carry the power of a curse.

See Separate Article: MYTHS, LEGENDS AND CREATION STORIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Bukidnon

The Bukidnon is a group that lives in the highlands of north-central Mindanao. Part of the larger Manobo group and also known as the Binokid, Binukid, Higaonan and Higaunen, they speak a Manobo language and have traditionally been farmers who raised corn, rice, sweet potatoes, bananas and coconuts and used water buffalo to plow their fields. Many have been assimilated and many are Catholics. The ones who remain closest to the old ways live near the headwaters of the Pulangi River on the slopes of Mount Kitanglad or Mount Kalatungan. [Source: Ronald K. Edgerton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the total population of Binukid Manobo in the early 2020s was 205,000 and 18,000 people spoke Western Bukidnon Manobo. Most practice traditional animist religions. About 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with 10 to 50 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. Bukidnon is also the name of landlocked province in north-central Mindanao that covers approximately 8,294 square kilometers (3,202 square miles). Most of the Bukidnon people live north of the eighth parallel on a broad grassland plateau situated at elevations ranging from about 300 to 900 meters (980 to 2,950 feet) above sea level. The area is dominated by 2,938-meter (9,639-foot) -high Mount Kitanglad, the second-highest peak in the Philippines after Mount Apo.

Bukidnon trace descent through both maternal and paternal lines, recognizing relatives on both sides as well as in-laws. Although most families now live in nuclear households, extended kin often reside in the same barangay and maintain strong reciprocal support ties, similar to broader Filipino practices. Arranged marriages, go-betweens and even child marriages were once common but these days most couples choose their own partners. Some couples have two marriage ceremonies: one using traditional rites and the other in the Roman Catholic church. It is common for couple to move in with bride’s parents for a couple months, so some worker for them before into their own house.

Among the Bukidnon, people who are good at settling disputes are held in high esteem. The division of labor among the Bukidnon favors men in that women do much of the work. Villages and districts are headed by chiefs called datus. Agriculture has traditionally been the basis of the Bukidnon economy, with about 95 percent of the population living in rural areas in the 1990s. The main crops are maize and rice, once grown entirely through swidden (slash-and-burn) farming but now often cultivated in small plowed plots near their homes. In remote areas, swidden agriculture continues alongside home gardens. Most farmers still rely on water buffalo or bullocks rather than machinery and harvest crops by hand. Other subsistence crops include sweet potato, cassava, gabi, beans, banana, coconut, and nangka, while coffee has emerged as a commercial alternative to abaca. Despite farming as their primary livelihood, many Bukidnon remain economically marginalized. Some young people work for mining and logging companies, typically in low-level positions, while a minority find more stable employment as civil servants, especially teachers or clerks. Small-scale crafts such as mat making, basketry, and embroidery supplement household income, though traditional arts like pottery and wood carving have largely disappeared.

See Separate Article: MYTHS, LEGENDS AND CREATION STORIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Bukidnon History

The Bukidnon trace their ancestry to a pre-Islamic, Proto-Manobo-speaking population believed to have lived along the southwestern coast of Mindanao, possibly near the mouth of the Rio Grande. Their oral epic, the Ulagina, recounts a migration led by the culture hero Agyu from the coast into the interior plateau, where they eventually settled. There, they established trade relations with the Islamicized Maguindanao to the south and the Hispanicized Visayans to the north. [Source: Ronald K. Edgerton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Spanish influence remained limited until the late 19th century, when Jesuit missionaries baptized thousands and encouraged settlement in towns modeled after the Philippine plaza system. Under American rule, Bukidnon became part of Agusan Province in 1907 and later a separate province in 1914, though it remained under direct American administration as a “Special Province” due to its predominantly non-Christian population. The Americans promoted cattle ranching and pineapple plantations, integrating many Bukidnon into the cash economy.

World War II devastated the cattle industry, and in the following decades large numbers of migrants moved into Bukidnon. The population rose sharply from about 63,000 in 1948 to over 400,000 by 1970, while the native Binukid-speaking population remained relatively stable. Today, the Bukidnon are generally grouped into three sectors: those in remote upland settlements who maintain more traditional lifeways; the majority who live in rural barangays and are more acculturated; and a smaller group in towns who largely identify with the broader Visayan mainstream.

The Bukidnon used to live in communal houses with as many as fifty families but now they live in single-family houses. Those that live in remote areas live in villages set up along trails or logging roads in raised houses made of thatch and bamboo. Those that live along major roads live in houses made of cinder blocks or wood, with a metal roof. The Bukidnon never practiced head hunting but did in engage in ritual sacrifice of captured enemies and kept slaves up into the early 20th century. Most slaves were captured or the victims of debt bondage. The Bukidnon generally avoided conflict but occasionally settled matters with violence. In 1975, hundreds of Bukidnon fought representatives of the Philippines government, leaving at least 34 and maybe as many as 200 dead.

Bukidnon Religion

Religion: In major towns, Bukidnon worship much like their non-Bukidnon neighbors, but in remote villages Christianity has been adopted more selectively. Many still believe in a hierarchy of supernatural beings led by Magbabáya, the supreme spirit. Christian symbols and practices have largely replaced older rituals and amulets, yet worship often remains focused on practical, short-term benefits rather than long-term salvation. Some communities have converted to Protestantism, while others—especially in remote areas—have joined Rizalian movements. Beliefs about death today are mostly Christianized, especially in towns. In remote areas, some still believe the soul travels to Mount Balatukan regardless of moral conduct and bury personal belongings with the deceased for use in the afterlife. Otherwise, Christian burial practices predominate. [Source: Ronald K. Edgerton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Even among Catholics a belief in spirits remains strong. These spirits have human characteristic and are appeased with sacrifices of food and drink. The traditional pantheon includes six categories of spirits: supreme sky and earth deities, guardian spirits of activities and natural elements, localized nature spirits (including malevolent busao), personal guardian spirits, and the gimokod, or multiple souls within a person. Ceremonies known as pamuhat involve prayers and offerings to spirits. The traditional harvest celebration, kaliga (kaliga-on), has largely been replaced by the town fiesta. In terms of arts, traditional crafts such as mat and basket weaving persist, and the Kaamulan festival has helped revive traditional clothing and some dances. However, indigenous songs, instruments, and performances have declined due to Western cultural influence.

Many Christian rituals, images and ceremonies are simply substitutes of traditional practices. The chief religious practitioners are Catholic priests but in villages that do not have priests villagers turn to shaman known as “baylan”. Both men and women can be balyan. Their primary duty is to preside over healing ceremonies. Most Bukidnon prefer Western medicine but seek out baylan when no other alternative is available. Traditional music and dances, some mimicking birds, are rarely performed anymore.

According to the Bukidnon Story of How the Moon and the Stars Came to Be: One day in the times when the sky was close to the ground a spinster went out to pound rice. Before she began her work, she took off the beads from around her neck and the comb from her hair, and hung them on the sky, which at that time looked like coral rock. Then she began working, and each time that she raised her pestle into the air it struck the sky. For some time she pounded the rice, and then she raised the pestle so high that it struck the sky very hard. Immediately the sky began to rise, and it went up so far that she lost her ornaments. Never did they come down, for the comb became the moon and the beads are the stars that are scattered about. [Source: Mabel Cook Cole, Philippine Folk Tales (Chicago: A. C. McClurg and Company, 1916), p. 124]

Subanen

The Subanen—also spelled Subanon, Subano and Subanun—are an indigenous people of the Zamboanga Peninsula in Mindanao, particularly in the mountainous areas of Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, and Misamis Occidental. The Subanen language is an Austronesian Language comprised of a set of closely related dialects, divided into two groups, Eastern and Western Subanen. Their name comes from suba or soba, meaning “river,” combined with the suffix -non or -nun, indicating origin or place; thus, “Subanen” means “people of the river.” The Total population of Subanen was 758,499 according to the 2020 census. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Subanen are mainly slash-and burn agriculturists or plot farmers that live in the forest interior in southern Mindanao. Historically, they lived in lowland and riverine areas. Over time, however, the arrival of other groups—including Moro communities and later migrants such as settlers from Luzon and the Visayas—led to increased competition for land. Colonial land policies and migration patterns gradually pushed many Subanen communities into the interior highlands, where they remain today. The Subanen are quite different from the lowlanders who live around them who are either Muslims or Christians. They have a history of being exploited and taken as slaves by their coastal Muslim neighbors. [Source: Charles O. Frake, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Subanen first appeared in seventeenth-century Jesuit accounts, which described them as living in scattered settlements with limited social integration. Exploitative trade and weak political organization have shaped Subanen relations with outsiders. Spanish efforts to resettle them into centralized villages failed. Prior to the American occupation in the early twentieth century, their primary external contacts were with Muslim traders and raiders operating from coastal and inland routes. Muslim groups established coastal trading centers that exchanged imported goods such as Chinese porcelains, gongs, beads, and iron for Subanen forest products, crops, and slaves. This relationship was highly unequal and exploitative, establishing a long-standing pattern of outsider dominance. The Subanen did not develop strong centralized political structures or organized military resistance to counter such exploitation. Although American rule reduced warfare and raiding, violence resurged after World War II, particularly during the Marcos era, amid escalating Christian-Muslim conflict. In several parts of the Zamboanga Peninsula, the Subanen were caught in the middle of these hostilities and often suffered from attacks by armed groups operating in the region.

Subanen Groups and Religion

The Subanen are divided into several subgroups based on geographic location and linguistic variation, reflecting the diversity of communities across the Zamboanga Peninsula. The main ones are: 1) Siocon (Western) Subanen; 2) Lapuyan (Southern) Subanen; 3) Sindangan (Central) Subanen; 4) Tuboy (Northern) Subanen; and 5) Salug (Eastern) Subanen. According to the Christian group Joshua Project in the early 2020s there were 8,600 Eastern Subanen, 216,00 Central Subanen, 155,000 Western Kalibugan Subanen, 32,000 Kolibugan Subanen, 108,000 Tuboy Subanen and 64.000 Lapuyan Subanen. [Source: Joshua Project, Wikipedia]

Most Tuboy Subanen, Central Subanen and Eastern Subanen practice traditional animist religions. About 5 to 10 percent of Eastern Subanen are Christians, with 0.1 to 2 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. About 0.1 to 2 percent of Tuboy Subanen are Christians. About 10 to 50 percent of Central Subanen are Christians, many of these being Protestant Evangelicals. About 60 percent of Western Kalibugan Subanen are Christians, with 10 to 50 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. About 14 percent of Lapuyan Subanen are Christians, with 4 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. Around 99.8 percent of Kolibugan Subanen are Muslims, with a handful being Christians (See Mor Groups).

The Subanen worldview includes gods, spirits, demons, and ghosts who interact closely with humans and can either help or harm them. Agricultural life is closely tied to ritual, with offerings of rice, meat, wine, and betel chew made throughout the farming cycle. Through séances led by mediums, deities and ancestors may request offerings, particularly for healing illness. Spiritual beliefs also shape conflict practices, as enemies may be harmed indirectly through rituals targeting their souls rather than through open warfare. [Source: Charles O. Frake, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Ritual specialists, usually older men but sometimes women, gain their roles through apprenticeship or divine revelation and occupy one of the few clearly defined social positions in Subanen society. In addition to religious rituals, the Subanen maintain extensive knowledge of medicinal plants, typically turning first to herbal remedies before performing costly offerings. Death prompts major ceremonies to ensure the spirit of the deceased safely journeys to the other world and joins the realm of spirits. Ancestors act as intermediaries in rituals, though long genealogies are not emphasized. Other stages of life, aside from birth and death, are marked by relatively little formal ritual, and there are no puberty ceremonies for either sex.

Subanen Life and Culture

The Subanen live in widely scattered settlements, practice slash-and-burn agriculture and plot farming, and, as of the 1990s, raised crops almost totally by hand, without plows or even hoes. Rice is their primary crop, supplemented by other root crops and vegetables. They also raise livestock such as pigs, chickens, cattle, and water buffalo. Their homes are typically rectangular structures built on stilts, with thatched roofs, and are often situated along hillsides or ridges overlooking their fields. They also gather a wide variety of forest products, hunt wild pigs and deer and fish and collect crustaceans from streams. The division of labor between men and women is very equal. Women even do much of the heavy labor such as clearing trees and slashing undergrowth. [Source: Charles O. Frake, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In the past, former swidden fields were first planted with secondary crops and then left to regenerate as fallow land. After as many as fifteen years—once a mature secondary forest had grown back—the area could be cleared again for cultivation. Kin groups and neighbors typically clustered their swiddens each year so they could cooperate in guarding and tending the fields. This system depended on the availability of ample forest land. In later decades, however, commercial logging, cattle ranching, lowland migration, and population growth reduced forest cover, forcing shorter fallow cycles or a shift to dry-field plow farming in grasslands.

Polygamy is sometimes practiced but is rare. Marriages are generally arranged between neighbors and kin. Bride prices are paid. If the groom’s family can’t raise enough money the groom may perform bride service for a year or more for the bride’s family. The Subanen believe in a coterie of spirits, demons, gods and ghosts. If these are not treated with respect they can cause illnesses or disrupt agriculture. Mediums are sought for their curing capabilities and to send curses.

Among the Western Subanen, the use of formal leadership titles was common and likely reflected earlier Muslim influence. Social control rested with respected individuals who possessed enough influence to mediate disputes and impose fines. Physical force was neither used nor threatened in local conflict resolution, though the possibility of government intervention remained an underlying concern. While verbal disputes occurred, actual violence was rare. Despite their dispersed settlements and lack of centralized political organization, the Subanen valued social gatherings, and legal proceedings, rituals, and feasts were lively events marked by rice wine drinking, music, dancing, storytelling, and animated participation by people of all ages.

Mandaya

The Mandaya are an animist ethnic group that lives along the Mayo River. In the old days, Mandaya youth filed and blacken their teeth upon reaching puberty. These acts were considered aids to beauty which helped a young person find a suitable partner for marriage.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project ther Mandaya population in the early 2020s was 288,000, including 12,000 Sangab Mandaya and 6,000 Karaga Mandaya Most practice traditional animist religions. About 5 to 10 percent of Mandaya are Christians, with 0.1 to 2 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. About 10 to 50 percent of Sangab Mandaya are Christians, with 5 to 10 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. About 5 to 10 percent of Karaga Mandaya are 50 Christians, with many being Protestant Evangelicals. [Source: Joshua Project]

According to the Children of the Limokon myth: In the very early days before there were any people on the earth, the limokon (a kind of dove ) were very powerful and could talk like men though they looked like birds. One limokon laid two eggs, one at the mouth of the Mayo River and one farther up its course. After some time these eggs hatched, and the one at the mouth of the river became a man, while the other became a woman. [Source: Mabel Cook Cole, Philippine Folk Tales (Chicago: A. C. McClurg and Company, 1916), pp. 143-144]

The man lived alone on the bank of the river for a long time, but he was very lonely and wished many times for a companion. One day when he was crossing the river something was swept against his legs with such force that it nearly caused him to drown. On examining it, he found that it was a hair, and he determined to go up the river and find whence it came. He traveled up the stream, looking on both banks, until finally he found the woman, and he was very happy to think that at last he could have a companion. They were married and had many children, who are the Mandaya still living along the Mayo River.

T'boli People

The T'boli (pronounced "Tiboli") live in the southern part of the province Cotabata, in the area around Lake Sebu, west of the city General Santos, in Mindanao. The total T'boli population is 181,125 according to 2020 Philippines census. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 147,000 Kiamba Tiboli in the early 2020s. Most practice traditional animist religions. About 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with 5 to 10 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. Only a few T'boli are Muslims. By one reckoning more than 95 percent still practice their animistic religion to some degree. They were hardly influenced by the spread of the Islam on the island. The Spaniards too, didn't succeed in Christianizing them during the Spanish colonial period. The main reason was that the T'boli withdrew to the hinterlands in the uplands. The T'boli and members of other indigenous tribes like the Higaunon, still believe in spirits who live on several places in the natural environment. [Source: Joshua Project]

In the past the T'boli practiced "slash and burn" agriculture in which they cleared a part of the forest by cutting the big trees and burning the lower and smaller trees and bushes, after which they use the cleared plots as arable land for some years without any fertilization. Rice, cassava and yams were the most important agricultural products. Next to that, the people went hunting or fishing for additional food. These days slash and burn agriculture is no longer possible. The forests have been lost to intensive economic activities and deforestation. At present The T'boli live in the mountains. Agriculture is their only source of income. Some foreigners, in cooperation with the aid organization Cord Aid, have provided aid to the group. Still the T'boli are very poor. The T'boli distinguish their selves, like all other "tribal Filipinos", by their colorful clothes and specific ornaments like rings, bracelets and earrings. [Source: Philippines.hvu.nl =]

The T'bolis of Mindanao have a bizarre funereal ritual. All night the dead man's body, housed in a bamboo coffin is trotted around his hut while his friends sing and chant. The body then gets a chance to relax for 15 days. After that the coffin is lashed to stalks in a bamboo grove where it stays until it falls apart. As a final gesture the man's hut is burned so it can not shelter his soul. Otherwise the T'bolis believe malevolent spirits would gather there and devour it. The T'boli men also, have a ritual where they place burning pieces of wood on their arms and see how long they can stand it.

The T'bolis and Ubos have another interesting custom. When a special male guest is invited to a man's house, in a demonstration of hospitality, he surrounded by a group of girls and women who for an hour or so gently fondle him, kiss him on the lips and coo seductively. Girls as young as six take part in this as do both married and single women. Because of the heavy doses of make-up it is impossible to accurately ascertain the girls' ages and their marital status. In reality it is all done out of friendship and hospitality not sexual desire. What is unforgivable however is touching a married woman on her heel or elbow.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026