ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN

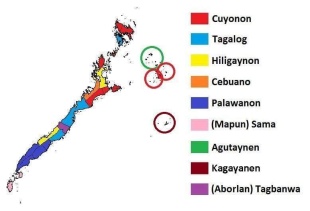

Palawan, often called the “Cradle of Philippine Civilization,” is home to several indigenous ethnic groups, including the Tagbanwa, Palawan, Batak, Molbog, and Tao’t Bato, as well as non-indigenous Cuyonon (Kuyono), Agutaynen (Agutayano), Kenoy, Moro, Klamain . and Kagayano.. Many of these communities live in mountainous or coastal areas, where they continue traditional practices such as farming, hunting, and fishing. Some are believed to be descendants of the island’s ancient inhabitants, including those associated with the Tabon Caves.

Many Muslim Moros live in the south, Many Batak and the Palawan still live in the rainforests. Many communities practice swidden (shifting) agriculture, cultivating crops such as rice, camote (sweet potatoes), and cassava. Religious beliefs vary, with some groups adhering to animism while others blend traditional practices with Islam or Christianity. People in Palawan are also known for skilled craftsmanship, including basket weaving, wood carving, and beadwork.

Among the oldest groups are the Tagbanwa, who live in central and northern Palawan and are divided into the Central and Calamian Tagbanwa. They are known for their indigenous script and rich ritual traditions. The Palawan, found in southern Palawan, traditionally practice hunting and gathering and are recognized for their distinctive musical instruments; they are divided into four regional subgroups. The Batak, a Negrito group in northeastern Palawan near Puerto Princesa, are one of the smallest indigenous populations in the province. In southern Palawan, particularly on Balabac Island, the Molbog are concentrated and are predominantly Muslim, maintaining close cultural ties with North Borneo. The Tao’t Bato, or “people of the rock,” live in caves in the Singnapan Basin valley. Meanwhile, the Cuyonon and Agutaynen, whose roots trace back to the Cuyo Islands, are generally considered more integrated into mainstream society than the other groups. [Source: Google AI]

Palawan is the fifth largest island in the Philippines. Home to about 1.2 million people, double the number in 1990, and covering 11,785 square kilometers (4,550 square miles), it is located north of Borneo and between the Sulu Archipelago and the South China Sea. Timber is an important industry on Palawan. However, there is concern that excessive logging and slash-and-burn farming will deplete the island's rainforests. The little arable land that exists on Palawan is largely devoted to subsistence farming. The island has important mercury and chromite deposits. During World War II, the island was the site of a Japanese massacre of American prisoners. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Palawans

The Palawans are one of the native peoples of Palawan as opposed to other Filipino groups that have moved there. They have traditionally lived in the central part of the island. Also known as the Pala.wan, Ira-an, Palawano, Palawanon, Paluanes, Palawanin, the Palawan have traditionally cultivated upland rice and built their homes in their fields. About 10 percent are Muslims, mostly those who live on the coast, and remainder practice traditional religion. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

The Palawan closely resemble the Tagbanwa and were likely once part of the same ethnolinguistic group. In the past, some Tausug settlers in Palawan referred to them as Traan, meaning “people in scattered places,” reflecting their pattern of living in dispersed homes across their farmland. Similar to the Yakan of Basilan, Palawan houses are often built far apart from one another. Their primary livelihood is subsistence agriculture, especially the cultivation of upland rice. They traditionally hunted using spears and bamboo blowguns. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Palawan consist of several subgroups. One small community in southwestern Palawan, living in the interior mountains, is known as the Taaw’t Bato, meaning “people of the rock.” They reside in the southern interior of the island, particularly within the volcanic crater area of Mount Mantalingaan. Some outsiders have mistakenly identified a separate group called “Ke’ney,” but this term is actually derogatory, meaning “thick” or “upriver people,” and is not used by the community to describe themselves.

Today, most Palawan communities are settled in the highlands of Palawan, stretching from just north of Quezon on the western side and Abo-Abo on the eastern side down to Buliluyan at the island’s southern tip. Their traditional religion preserves an ancient belief system once widespread in the central Philippines before Spanish colonization in the 16th century. This faith blends animist traditions with elements of Hindu and Islamic influence. Some Palawan have adopted Islam through contact with their southern Molbog and Palawani neighbors, while a smaller number have converted to Protestant Christianity through recent missionary efforts.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 16,000 Southwest Palawano, 13,000 Central Palawano and 14,000 Palwano around Brooke’s Point in the early 2020s. Most practiced traditional animist religions. About 5 to 10 percent of the Southwest Palawano are Christians, with many of these being Protestant Evangelicals. About 2 to 5 percent of the Brooke’s Point Palawano are Christians, with 0.1 to 2 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. [Source: Joshua Project]

Tagbanuwa

The Tagbanuwa are one of the indigenous people of Palawan. Also known as the Tagbanoua and Tagbanua, they have traditionally grown rice, maize, millet, taro, cassava and sweet potatoes and fished and hunted. They are known as the primary harvester of Manila copal—a gum found in the bark of a kind of pine tree. Their religion focuses on deities, evil spirits and spirits of relatives but does not involve ancestor worship. Upland rice is regarded as a sacred gift. A key ritual in their cult of the dead is the pagdiwata, a ceremonial gathering where rice wine—fermented from their harvest—is offered and shared. [Source: Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Tagbanwa have traditionally lived in central and northern Palawan. Their name means “people of the world.” Central Tagbanwa communities live along the western and eastern coasts of central Palawan, especially in the municipalities of Aborlan, Quezon, and Puerto Princesa. The Calamian Tagbanwa are located farther north, in areas such as the Baras coast, Busuanga Island, Coron Island, Linapacan, Calibangbangan, and parts of El Nido, including a designated cultural preservation area.

Rice cultivation is central to both their economy and spiritual life. Their religious system places strong emphasis on the veneration of the dead and reverence for deities believed to inhabit the natural world. Distinctive elements of Tagbanwa culture include their indigenous script and language, the practice of kaingin (swidden farming), and beliefs in soul-relatives. The Tagbanwa are also highly skilled artisans. They are known for their basketry and wood carving, as well as for finely crafted body ornaments such as combs, bracelets, necklaces, and anklets made from wood, beads, brass, and copper.

Tagbanuas residing in the Calamianes fish only with hook and line, grow cashew nuts, collect coconuts and gather nests for bird’s nest soup. Few have access to Western medicine. Instead they use things like guava leaves to treat upset stomachs. They know how to treat poisonous sweet potatoes to make them edible. They have also found a substance that stuns fish without cyanide.

Tagbanuas residing in the Calamianes islands north of Palawan have been granted land and water rights to several islands. Some of the islands are left untouched because they are sacred and have burial grounds. Others are open to tourists who pay a small fee to enter. The money from the frees is used to buy food and goods they need.

Batak

The Batak are a Negrito group that lives in northeastern Palawan. Also called Tinitianes and not to be confused with Batak of Sumatra, Indonesia, they numbered 1,531 in the 2020 Philippines census and 3,900 in a Joshua Project tally in the early 2020s. They are related to the Aeta on Luzon and similar groups in Indonesia.

The Batak have long combined a hunting-and-gathering with the seeding of useful food plants, kaingin (slash-and-burn cultivation), and trade. For centuries, they maintained important commercial ties with maritime peoples of the Sulu region, exchanging forest and natural products for manufactured goods. Beginning around 1900, Filipino settlers and other migrants moved into the Batak’s traditional territories, leading to the gradual loss of Batak land and resources. In the 1930s, the government attempted to create Batak reservations in the coastal plains, but these areas were soon occupied and overwhelmed by Filipino migrants during the 1950s, forcing the Batak to retreat inland into the island’s interior. [Source: Wikipedia]

By the mid to late twentieth century, emigrant farmers—mostly from Luzon—had pushed the Batak from their preferred coastal gathering areas into the mountains. Residing in less fertile environments, the Batak sought to supplement their livelihoods by collecting and selling various non-timber forest products, including rattan, tree resins, and honey.

See Separate Article: NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Taaw’t Bato

The Taaw’t Bato (Tau’t Bato) are a small subgroup of southwestern Palawans living in the Singnapan Basin of southern Palawan, which lies between 2,086-meter (6,844-foot) Mount Mantalingahan, the highest mountain in Palawan, to the east and the coast to the west, with the municipality of Quezon to the north and remote southern regions beyond. During certain seasons, they reside inside caves within the crater of an extinct volcano, building raised-floor dwellings within the rock shelters, while others construct homes along open mountain slopes.Taaw’t Bato means “people of the rock.” According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Taaw’t Bato village in the early 2020s was 500. Most practiced traditional animist religions and 2 to 5 percent were Christians, with Protestant Evangelicals accounting for 0.1 to 2 percent of the total population.

Taaw’t Bato maintain a highly traditional lifestyle, including simple forms of dress. Men commonly wear bark or cloth loincloths, while women wrap cloth around their lower bodies as skirts; some women also wear market-acquired blouses. Compared to other Palawan groups, their artistic work is generally simpler, though their basketry can be highly skilled. Around cave entrances, they build light but sturdy lattice frameworks from saplings lashed together and anchored to rock crevices, allowing access to elevated sleeping platforms (datag) and storage structures (lagkaw). [Source: Wikipedia]

The Taaw’t Bato practice swidden (shifting) cultivation, with cassava as their primary staple. They also grow sweet potato, sugarcane, malunggay, garlic, pepper, beans, squash, tomatoes, and pineapple. Hunting and foraging supplement their diet, and wild pigs are often caught using spring traps. Trade takes place through sambi (barter), particularly exchanging forest and farm products for marine fish from coastal communities such as Candawaga, and dagang (monetary exchange), involving goods like almaciga resin and rattan.

Their basic social unit is the ka-asawan (marriage group), which may extend into compound or extended family households. Several households form a bulun-bulun, meaning “gathering,” typically sharing a single cave or swidden settlement area. Membership in a bulun-bulun is defined by close cooperation and the sharing of food and resources. Because of their cultural distinctiveness, the Philippine government has declared parts of their territory off-limits to outsiders to protect them from exploitation. However, mining concessions—particularly for nickel near Mount Gangtong and the Mantalingahan range—have threatened some communities. In recognition of the group, a species of gecko, Cyrtodactylus tautbatorum, was named in their honor.

Combating Malaria in the Taaw’t Bato Region

Malaria is still problem in areas of Palawan where the Taaw’t Bato, Sarah Newey described the effort to treat and get rid of the disease in The Telegraph: A bulky microscope, stacks of bed nets, and a cooler packed with vaccines are hardly typical gear for a two-hour trek through a mountainous rainforest. Yet the health workers shoulder the awkward equipment—some carrying it by hand, others loading it into woven backpacks—and set out shortly after 7 a.m., unfazed by dark clouds gathering overhead. [Source Sarah Newey, The Telegraph, August 27, 2024]

Their 2.2-mile journey takes them past bright green rice paddies and beneath towering trees, through muddy streams and thick grass, down steep rocky paths, and across a swaying suspension bridge. “For us, it’s just another Tuesday at work,” says midwife Neita Bagupalan as a colleague slips on the slick trail. She explains that the hike is exhausting in the heat and treacherous in the rain, but it remains the only way to reach isolated communities deep in the mountains. At last, they arrive at a modest wooden health outpost tucked into the foothills of Mount Mantalingahan. The site is inaccessible by car or motorbike and surrounded by dense jungle. Despite its simplicity, the station provides critical services: vaccinating children against diseases like polio, treating malnutrition, and advising expectant mothers.

Malaria remains a serious concern in these remote indigenous communities, where slash-and-burn farming, high-altitude living, heavy mosquito exposure, and limited access to healthcare complicate eradication efforts. Health officials stress the need to work closely with local residents to make prevention strategies effective. Even with threatening monsoon skies, the team presses on—grateful that a newly completed road has shortened what was once an even longer journey.

By the time they arrive, the station is crowded. The atmosphere feels almost festive: alongside testing and weighing stations, a large speaker blasts Filipino pop music between public health talks, and food is distributed to visitors. Children and chickens wander freely, adding to the lively scene. Eldino Goling, a Tau’t Bato elder recalls when malaria was the community’s leading cause of death. Through collaboration with health workers, awareness and treatment have improved. “If gatherings are fun and effective—and there’s food—people are more likely to come,” he says.

One father, Ristan Rentak, walked an hour and a half downhill after his four-year-old son, Argil, developed fever and headaches. A rapid test confirms malaria, and the boy begins antiviral treatment while the family stays in isolation at the outpost to prevent further spread. In recent years, some indigenous families have relocated closer to newly established villages that integrate healthcare services, improving access and offering hope for healthier futures.

Molbog

The Molbog—also known as Malebugan or Malebuganon—are the dominant indigenous group in the southernmost municipalities of Palawan, particularly Balabac and Bataraza, as well as parts of Brooke’s Point and Rizal. Smaller Molbog communities are also found in Mapun (Tawi-Tawi) and along the northern coast of Borneo. They are the only indigenous group in Palawan whose population is overwhelmingly Muslim, with estimates placing their number at around 20,000–24,000 people, more than 99 percent of whom adhere to Islam. [Source: Wikipedia, Ethnic Groups Philippines]

Balabac Island has long been regarded as the Molbog homeland, predating Spanish colonization. Some accounts describe them as having ancestral links to northern Borneo, while linguistic and historical evidence suggests they were originally an indigenous Palawan subgroup who later converted to Islam. Through sustained contact and intermarriage with Tausug and Samal groups under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate, the Molbog developed a distinct identity. Villages were historically led by religious authorities under Sulu datus, and today the Molbog language reflects Tausug and Jama Mapun influences. As practicing Muslims, they observe the Five Pillars of Islam and incorporate Arabic chants into religious life.

The name “Molbog” is believed to derive from malubog, meaning “murky or turbid water,” referring to the muddy coastal waters of Balabac caused by inland flooding. Historically, Palawan served as a trading hub between the Philippines and Brunei, with Tausug merchants stopping to resupply. The Molbog engaged in fishing, subsistence farming, and barter trade with nearby Sulu communities and markets in Sabah, Malaysia. Coconut cultivation remains central to their economy, with copra as a key product.

Molbog culture reflects a close relationship with nature, especially the pilandok (Philippine mouse-deer), an animal native to the Balabac Islands and featured in local folklore. In popular tales, the pilandok appears as a clever trickster and protector of the environment, outwitting greedy or destructive figures. Traditional beliefs and customs—often tied to health, safety, and community well-being—remain important, particularly in more isolated mountain settlements.

Ceremonial life includes dance rituals performed during weddings, thanksgiving celebrations, and healing rites to offer prayers and seek blessings. Another traditional practice, now fading, is the making of fabric from bamboo fibers, once woven into clothing and now preserved mainly for cultural demonstrations. Today, while Palawan has become increasingly diverse due to migration, Muslims—including the Molbog, Tausug, and Jama Mapun—form the majority population in the province’s southernmost municipalities, where Molbog heritage continues to shape local identity.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026