TAGALOGS

Tagalogs are the dominant ethnic group in the Philippines both politically and culturally. Also known as Pilipino, they have traditionally lived in the central Luzon Plain around Manila Bay. Their language is the basis of Pilipino, the national language and the primary language taught in schools. Tagalogs are regarded as proud, boastful and talkative. They are dominate in business, government and the media. Many of their customs involving marriage , death and life events are rooted in Catholic traditions. The word Tagalog is derived from “taga ilog”, meaning “inhabitants of the river.”

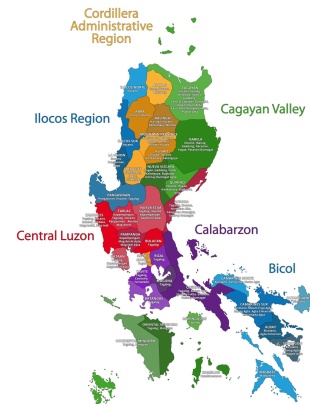

The Tagalog-speaking region is situated around toward Manila Bay and is largely concentrated within roughly 80 to 320 kilometers of the anila megalopolis on Luzon. Geographically, it lies within the Tropic of Cancer, extending from about 10° to 16° north latitude and from 119° to 123° east longitude, and includes the provinces of Bataan, Bulacan, Rizal, Cavite, Batangas, Laguna, and Quezon, as well as parts of Nueva Ecija and Camarines Norte, the islands of Marinduque and Polillio, portions of Mindoro and Palawan, and numerous smaller islands. Its terrain ranges from mountains rising to about 2,000 meters and forested uplands covered with tropical rain forest to diverse lowland coastal and inland environments. [Source: Charles Kaut, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The total number of Tagalog the Philippines is roughly 30 million and they make up about 28 percent of the Philippines population. In 1991, the population of this Tagalog “heartland,” known as Katagalugan, exceeded 10.9 million people living in an area of approximately 23,920 square kilometers. Several hundred thousand native Tagalog speakers live elsewhere in the Philippines and abroad. |~|

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

AETA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, LIFE, HUNTING, HEALTH factsanddetails.com

AGTA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, FOOD factsanddetails.com

CHINESE IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

Tagalog History

Before the arrival of the Spanish the Tagalogs had a writing system based on Sanskrit and an advanced metallurgy technology and lived in loose “confederations” under a complicated social system with hierarchical ranking and religion system that varied regionally. Chinese traders passed through the region with some regularity and Islamic sultanates had been established in area. Under the Spanish, the Tagalogs converted to Christianity and adopted more Western ways.

It can be argued the history of the Tagalog is the history of the Philippines itself. The great Indonesian empires of Srivijaya and Majapahit left lasting marks on Tagalog language, religion, and technology through trade and settlement. For centuries, Chinese traders used ports along Luzon’s western coast as stopovers in their commerce with the Spice Islands and local markets. By the time the Spanish arrived, Islamic sultanates had already been established around Manila Bay, signaling the region’s deep integration into wider Asian trading and religious networks. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

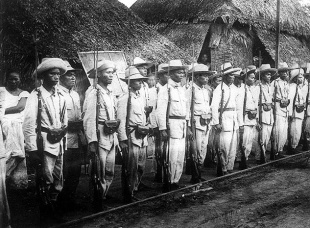

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Manila emerged as one of the world’s major seaports, serving as the transshipment hub of the famed Manila galleon trade that exchanged Mexican silver for Chinese silks and luxury goods. By the mid-nineteenth century, resistance to Spanish rule had grown strong in the Philippines, particularly in the Tagalog region, which produced national heroes such as José Rizal, Andrés Bonifacio, and Emilio Aguinaldo. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, a full-scale insurrection was already under way and continued against American forces until 1902.

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Tagálogs inhabit Manila and the adjacent provinces. We speak in all kindliness when we say that they are distinguished by a certain restlessness of disposition, by a considerable degree of vanity. They are not so given to labor as some others—for example, the Ilokanos, to whom they are measurably inferior in point of trustworthiness. More numerous than any other tribe except the Visayans, they are also wealthier and better educated. Some of them have therefore earned and achieved distinction, but these are exceptions, for in general they are characterized by volatility and superficiality. They are more mixed in blood than other tribes. If independence were granted “in all probability, a Tagálog oligarchy would be formed; for the capital, Manila, is Tagálog, the adjacent provinces are Tagálog, the wealthy class of the Islands on the whole is Tagálog, and there is no middle class anywhere. The mere fact that the capital is situated in the Tagálog provinces would perhaps alone determine the issue, apart from the fact that the Tagálogs are the dominant element, of the native population. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Tagalogs have largely dominated the political, economic, and cultural landscape of the Philippines since independence in 1946, although this dominance is often characterized as a "Tagalog-centric" national structure. The concentration of power in Metro Manila—located within the Tagalog-speaking region—has created a "capital city advantage," allowing Tagalog culture and language to set the tone for national government and politics. Tagalog serves as the basis for the national language, Filipino. While the Philippines is highly linguistically diverse, Tagalog-based media and educational materials have historically predominated, leading to its widespread use over other major languages like Cebuano (13 percent) and Ilocano (9 percent . The central government's focus on Manila has historically led to regional development disparities, with Tagalog-dominated regions receiving significant economic focus. [Source: Google AI]

Tagalog Language and Religion

Tagalog is the predominant dialect of the Luzon mainland. It is related to Malay and Indonesian and is part of the Malayo-Polynesian subgroup of the Austronesian language family. Filipino is the common language used between speakers of different native languages, which are closely related but not mutually intelligible. Pilipino, a language based in Tagalog, is technically the national language of the Philippines but in actuality it is primarily the local language of people in the Manila area and the plains of Luzon. Many people outside of Luzon and Manila understand it because newspapers, film scripts and magazines are written in Tagalog and radio and television shows are broadcasts are broadcast in the language.

Tagalog speakers in the Philippines have many ways of greeting other people. It is common also to hear them say "Hi" or "Hello" as a form of greeting, especially among close friends. There are no Tagalog translations for these English greetings because they are basically borrowed terms. Below are a few Tagalog greetings that are important to learn if one wants to endear himself/herself to Filipinos. [Source: Philippines Department of Tourism]

Tagalogs are largely Roman Catholic, though several other organized religious groups also have substantial followings. Most Protestant denominations are present, usually in small numbers, but two locally founded churches—the Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ) and the Aglipayan Church, established by Gregorio Aglipay after his break with Catholicism—command significant memberships. In addition, numerous local sects and cults continue to exist. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Religious belief generally operates on two levels. One consists of the formal doctrines of Roman Catholicism or other established religions; the other involves local interpretations and personal adaptations of these doctrines. Many people seek direct encounters with unseen forces through penitence and acts of contrition. Life in a region frequently affected by typhoons, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and social disruption reinforces a traditional fatalism summed up in the expression bahala na, meaning “it is all up to God.”

Most towns have resident Roman Catholic clergy serving a central church (simbahan) and smaller chapels (bisitas or ermitas) in surrounding barrios. Almost every community holds an annual fiesta in honor of a patron saint, the Virgin Mary, or a local image of Christ, typically organized by a dedicated group of volunteers responsible for that year’s celebrations. In addition to Christmas and Easter and their associated observances the feast of Saint John the Baptist is widely celebrated, particularly in connection with rivers and other bodies of water. Good Friday often features dramatic acts of penitence, including self-flagellation and, in some places, ritual crucifixion at sites regarded as especially sacred. Baptism, confirmation, marriage, and funerals are regular and significant events throughout the life cycle.

See Separate Article: MYTHS, LEGENDS AND CREATION STORIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Tagalog Society and Family

Tagalog society appears to be strongly kinship-based, though non-kin are generally incorporated into networks of reciprocal obligation and interaction. Horizontal class distinctions based on wealth and proximity to economic resources and political power are crosscut by vertical genealogical and ritual ties of kinship, linking the upper and lower classes into pyramidal networks of various levels. These networks' boundaries and internal relationships are constantly being rearranged. [Source: Charles Kaut, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The fundamental kin unit is the sibling group, kamagkapatid (kapatid = sibling). Special terms distinguish birth order, such as panganay (firstborn) and bunso (youngest), and in some families Chinese-derived terms indicate numerical rank. Each marriage forms a nuclear family, kamaganakan (anak = child), embedded within a bilaterally extended network tracing descent from recognized ancestors or sibling groups. These extended families connect through marriage into broader groupings known as angkan or pamilia, typically identified by patrilineally inherited surnames that women may retain after marriage. Kin ties stretch widely, and even strangers may compare relatives’ names to uncover connections; relationships are reinforced through reciprocity, expressed in utang na loob—a “debt of inner will”—created by unsolicited gifts and strongest toward God and parents, the givers of life. Ritual sponsorship at baptism (binyag), confirmation (kumpil), and marriage (kasal) further extends or intensifies kinship bonds beyond blood ties.

Marriage (kasal) generally follows Roman Catholic prescriptions, though cousin marriage at varying degrees occurs depending on local custom. There is often social pressure to marry within the third degree of kinship and, if possible, within the local community. Divorce (diborsiyo) has long been illegal, but separation (hiwalay) does occur. Marriage reinforces alliances within the extended kin network and sustains existing obligations.

Tagalog Life and Culture

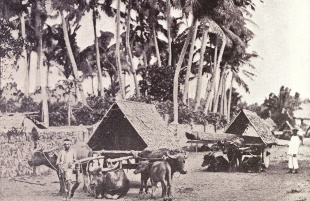

In the lowlands, where irrigated rice farming sustained communities, Tagalog settlements were originally established along rivers and waterways. Before the Spanish introduced highways and railroads, these waterways served as the main routes of transportation and trade. As roads and rail lines spread during the colonial period, homes began to cluster along them, even in upland regions where houses had typically been scattered in small groups near fields and water sources. In both lowland and upland areas, larger communities functioned as marketplaces and religious centers. Coastal villages likewise formed near reliable sources of fresh water. [Source: Charles Kaut, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

With the arrival of Roman Catholicism under Spanish rule, settlements became more centralized, often organized around a church, chapel, or shrine—possibly continuing earlier precolonial patterns of sacred centers. By the early nineteenth century, major towns featured developed central plazas surrounded by dense populations. Manila and several provincial capitals grew into important urban centers. While still deeply connected to Tagalog society, Manila also emerged as a focal point linking many regions of the country.

Tagalog houses have traditionally fallen into two main types: movable and permanent. Movable dwellings were typically raised on stilts and constructed from bamboo and wood, with thatched or metal roofs. More durable masonry houses were once found mainly in towns and cities, though urbanization has since expanded their presence. Today, Manila and other urban areas in the Tagalog region are evolving into fully metropolitan districts.

Tagalogs have long been recognized for their artistic achievements. Since the establishment of printing in Binondo, Manila, in 1593, a rich literary tradition has flourished in Tagalog, as well as in Spanish and English. Early works included poetry printed in 1606 by Fernando Bagonbanta. Notable figures include Francisco Baltazar (Balagtas), author of the classic Florante at Laura and inspiration for the poetic debate form known as the balagtasan, and José Rizal, whose novels Noli me tángere and El filibusterismo led to his execution in 1896 and secured his status as a national hero. Today, Tagalog remains central to a vibrant film and television industry, and traditional forms such as the kundiman, or love song, continue to endure.

Ilocano

The Ilocano are the third largest ethnic group in the Philippines after the Tagalog and Bisaya-Cebuano. Also known as Kailukuán, Kailukanuán, Ilokáno, Ilóko, Ilúko, or Samtóy, the Ilocano are originally from the Hiligayon region and the Ilocos coast of northwest Luzon and have since spread throughout northern and central Luzon, particularly in the Cagayan Valley, the Cordillera Administrative Region, and the northern and western areas of Central Luzon. They make up about 9 percent of the Philippines population and numbered 8,746,169 in 2020 Philippines census. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ilocanos are seen as hardworking, aggressive and worried about the future. Beyond northern Luzon, many Ilocanos live in Metro Manila, Mindoro, Palawan, and Mindanao. Large Ilocano communities also settled in the United States, especially in Hawaii and California, due to heavy migration in the 1800s and 1900s. Ilocano culture combines Roman Catholic beliefs with older animist traditions. Their way of life has long been shaped by farming and strong family and community ties.

Before the Spaniards arrived, the Ilocanos called themselves “Samtóy,” a shortened form of phrases meaning “our language.” The name “Ilocano” (or “Ilokano”) is the Spanish-influenced plural of “Ilóco” or “Ilóko.” It comes from the prefix i- (“from”) and words meaning “sea” or “bay.” The name reflects their origins in coastal areas, so “Ilocano” means “people from the bay.”

The Language of the Ilocanos is called Iloco or Iloko. There are about 8.7 million native speakers and about 2 million people who speak it as their second language. Iloco is classified under its own branch within the Northern Philippine subgroup of the Austronesian language family. It is closely related to other Austronesian languages in Northern Luzon, and is slightly mutually intelligible with the Balangao language and the eastern dialects of the Bontoc language.

Most Ilocanos are trilingual. Their first language is Iloco, and they commonly speak Filipino (Tagalog) and English as second languages. Because of migration and close contact with other ethnolinguistic groups, many Ilocanos also speak additional regional languages. In the Cordillera Administrative Region, Iloco functions as a lingua franca among different Igorot groups. It is widely used as a second language there. These people make up the last majority of the two million people who speak Iloco as their second language.

Ilocano History

The Ilocano are one of the Austronesian peoples of northern Luzon. Their distant ancestors were part of early "Out of Taiwan" migrations that moved south through the Philippines thousands of years ago. traveling by wooden boats such as the biray or bilog for trade and transport. The ancient Ilocanos were both farmers and seafarers who took part in active regional and international trade. They exchanged goods with the Cordillerans, Pangasinans, Sambals, Tagalogs, Ibanags, and foreign merchants from China, Japan, and other parts of Maritime Southeast Asia. This trade was linked to wider networks across the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. Common trade items included porcelain, silk, cotton, rice, beeswax, beads, gems, and precious minerals, especially gold. These economic activities helped connect Ilocano communities to broader Asian trade systems.

Ilocano settlements, called íli, were similar to Tagalog barangays, with smaller neighborhood units known as purók. Society was hierarchical and led by an agtúray or ári, a chieftain whose authority often depended on wealth, strength, and wisdom. He was assisted by a council of elders in governing the community. Below him were the babaknáng, wealthy individuals involved in trade who could rise to leadership. The lower classes included tenant farmers (kailianes), servants (ubíng), and slaves (tagábu), who had fewer rights and opportunities.

Spanish colonization began in 1572 under Juan de Salcedo, who led an expedition north after securing Pangasinan. The Spaniards encountered settlements collectively called Samtoy and renamed the region Ylocos and its people Ylocanos. Although the Ilocanos were peaceful coastal traders, they resisted Spanish tribute demands and forced conversion to Christianity. One early act of resistance was the Battle of Purao, where locals refused to pay tribute, leading to bloodshed. Despite resistance, Salcedo subdued key settlements, and Vigan became the center of Spanish political and religious control.

In 1660, the Malong Revolt challenged Spanish rule when Andres Malong declared himself king and sought Ilocano support. Ilocano leaders refused to join him, prompting an invasion led by Don Pedro Gumapos. Although Gumapos initially defeated local defenses and sacked towns like Vigan, Ilocano communities regrouped and used guerrilla tactics, often with Tinguians as allies. After Malong was defeated elsewhere, Spanish and Ilocano forces overcame Gumapos in major battles. Gumapos was captured and executed, and the Ilocanos’ resistance helped secure the region for Spanish rule while demonstrating their military resilience and strategic unity. There were other revolts in the 1600s, 1700s and 1800s.

Ilocano revolutionaries made significant contributions to the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898) by employing their unique fighting techniques and weaponry. They were particularly notable for their leadership and military efforts under General Manuel Tinio, a central figure in the northern resistance against Spanish forces. Tinio's brigade occupied the entire western part of Northern Luzon, including Pangasinan and the four main Ilocano provinces: Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, Abra, and La Union, as well as the comandancias of Amburayan, Lepanto-Bontoc, and Benguet.

Ilocano Religion and Burial Customs

The Ilocanos are predominantly Roman Catholic, which is a result of the introduction of Christianity during the Spanish colonization of the region in the mid-16th century. Many Ilocanos integrate indigenous rituals and precolonial customs into their religious practices, creating a form of folk Catholicism. This blend of Catholic doctrine and animist traditions has played a central role in shaping the spiritual lives and cultural practices of the Ilocanos. [Source: Wikipedia]

Before Spanish contact, Ilocano society was centered on animistic and polytheistic beliefs. They believed that anitos, or spirits, lived in nature and influenced daily life. Important deities included Buni, the earth god; Parsua, the creator; and Apo Langit, lord of the heavens. Because Ilocano communities were scattered, different areas developed their own versions of these beliefs and rituals. Their religious practices were also shaped by contact with neighboring groups such as the Igorots and Tagalogs, as well as by Chinese traders.

Traditional Ilocano beliefs that have merged with Roman Catholicism include recognition of katawtaw-an — spirits linked to unbaptized infants. Crocodiles, known as bukarot, are respected as ancestral beings. To avoid bad luck, people offered them the first catch of the day, a ritual called panagyatang. The Sibróng was connected to headhunting and human sacrifice. It was usually performed when a community leader or member of the principalía died, with the belief that it would ensure safe passage to the afterlife. There were two main forms of sibróng. In one form, a victim’s head was taken and buried in the foundation of a bridge or building to symbolize strength and provide protection. In another form, called panagtutuyo, a dying person would raise fingers to show how many people should be sacrificed to accompany their soul. In some cases, cutting off fingers was done as a symbolic substitute for taking lives. Placing human heads in building foundations was believed to spiritually guard the structure from harm.

Ilocanos have their own funeral and burial traditions, known as the pompon or "burial rites". An example would be how a dead husband is prepared by the wife for the wake, known in Ilocano as the bagongon. Typically, only the wife will cloth the corpse, believing that the spirit of the spouse can convey messages through her. Placement of the coffin is also important, which is to be at the center of the home and must be corresponding to the planks of the floorboards. Lighting a wooden log in front of the house is also customary because the smoke assists the spirit of the dead towards heaven. This log is kept in flames during the wake to repel wicked spirits. The ceremonial attire of the female family members for the vigil is clothing with black coloration. Their heads and shoulder area are shrouded with a black handkerchief known as the manta. [Source: thefuneralsource.org +++]

Funeral Burial superstitions of the Ilocano people include closing all windows first before taking the casket out of the home, preventing any part of the coffin to hit any part of the dwelling (to prevent the spirit of the dead from loitering to bring forth dilemmas to the household; to some Filipinos, a coffin hitting any object during a funeral means that another person will soon die, and washing the hairs of family members with a shampoo known as gogo (to remove the influence of the spirit of the departed). rice cakes and basi to attendees after each prayer offering session. On the ninth night, a feast is held after the praying or novena. They will again recite prayers and a feast after one year. +++

Ilocano Society

In the pre-colonial period, Ilocano communities were called íli, with smaller neighborhoods known as purók. Society was organized into a clear class system based on status, family background, and service to the community. At the top was the agtúray or ári (chief), who ruled with the help of a council of elders. Leadership was usually hereditary, though capable women could inherit if no male heir was fit to rule. Below the chief were the babaknáng, the wealthy class involved in regional and international trade, followed by the kailianes, who supported the chief through labor and service.

Most of the population were katalonan, tenant farmers who grew rice, taro, and cotton and supported the local economy. At the bottom were the ubíng (servants) and tagábu or adípen (slaves). People could become slaves through debt, war, punishment, or inherited obligations. Although slavery placed individuals at the lowest social level, it was not always permanent. This structured but flexible hierarchy shaped Ilocano life before Spanish rule.

During the Spanish colonial period, much of this hierarchy remained but was reshaped under colonial authority. The traditional elite became the principalia, serving as local officials such as gobernadorcillo and cabeza de barangay. These leaders collected taxes, maintained order, and acted as intermediaries between the Spanish government and local communities. They enjoyed privileges such as tax exemptions and honorary titles like “Don” and “Doña.” Their status was usually hereditary, though it could also be granted by royal decree.

Below them were the cailianes, free tenants who worked the lands of the elite in exchange for a share of the harvest. They also served as skilled workers, including artisans and healers, whose roles were vital to the community. Their relationship with the elite was based on reciprocity, with labor exchanged for protection, food, or goods. At the bottom were the adipen, who remained dependent on masters for survival. While they had little freedom, some were able to gain liberty by repaying debts or through manumission, showing that even under colonial rule, social mobility was limited but possible.

Ilocano Clothes and Appearance

Ilocano men and women traditionally wore an upper garment called the bádo or báru, similar to the Itneg koton and fine Indian crepe fabrics. Silk clothing was reserved for the upper class. Women wore short, tight-fitting, handwoven skirts with colorful horizontal stripes, along with white short-sleeved blouses and loose striped jackets. Men wore collarless, waist-length jackets with short, wide sleeves, paired with a long loincloth known as the baág, anúngo, or bayakát, often brightly colored and decorated with gold threads. Some men also wore trousers similar to those of the Tagalogs.

Hair care was important for both men and women. They used natural mixtures made from tree bark, coconut oil, musk, perfumes, and gogo to keep their hair shiny and black. Lye from rice husks was also used and is still found in some areas today. Women typically styled their hair in buns on top of the head. Men removed facial hair with clam-shell tweezers, maintaining a clean-shaven look.

Teeth were carefully maintained and sometimes polished or shaped using stones and betel nut husks. Some people colored their teeth red or black for preservation, a practice also seen among the Igorots. Wealthy individuals, especially women, decorated their teeth with gold for beauty and strength. Both men and women wore gold jewelry, including thick rings in pierced earlobes and earrings called arítos. Larger ear piercings often showed higher social status.

Betel nut chewing, known as mama, was a common tradition. Men also wore a headdress called the bangal, a long cloth wrapped around the head or draped over the shoulder. Its color signified achievements—red meant the wearer had killed someone, and striped designs were reserved for those who had killed seven or more. After Spanish contact, hats gradually replaced the bangal. Some Ilocanos also had tattoos called batek, butak, or burik, usually on the arms or hands. Though less common than among the Igorots or Visayans, tattoos served as body art and symbols of status.

Ilocano Culture

The Ilocanos are known for their rich tradition of arts and crafts, which have been passed down through generations. These include weaving (abel), woodcarving, and pottery (damili), which once served practical needs such as making clothing, jars, and cooking tools. Today, these crafts remain culturally important and also support local economies. Artisans now create both traditional and modern products for wider markets. These skills reflect Ilocano creativity and strong ties to heritage. [Source: Wikipedia]

Weaving, called abél, is one of the most valued Ilocano crafts. The process, known as panagabél, uses wooden pedal looms to produce inabél cloth, prized for its softness and durability. Different provinces in the Ilocos Region have unique patterns, such as binakul, believed to protect against evil spirits. Other weaving styles include pinilian (brocade), suk-suk, and the ikat tie-dye method. Common designs feature geometric and nature-inspired patterns like stars, fans, and animal shapes.

Alcoholic Drinks made by the Ilocanos include basí and tapuy (or binubudan). Basí is made from fermented sugarcane juice and plays an important role in rituals for birth, marriage, and death. It is prepared in clay jars (burnáy) and may ferment for months or even years, sometimes turning into vinegar. Tapuy, on the other hand, is a rice wine made by fermenting cooked rice with yeast. Both drinks are part of shared cultural traditions in northern Luzon.

Traditional Games also form part of Ilocano culture. One example is kukudisi, a children’s game that uses two sticks and requires skill, coordination, and strategy. Players take turns launching and striking a small stick to see who can send it the farthest. The game encourages physical ability, creativity, and friendly competition. It also reflects the resourcefulness of rural communities, using simple materials found in everyday life.

Music is another important part of Ilocano identity, expressing experiences from birth to death. Traditional forms include duayya (lullabies), dállot (improvised wedding or courtship chants), and dung-aw (funeral laments). Dállot is a poetic chant often performed at joyful gatherings and showcases quick thinking and creativity. Ilocano folk songs commonly focus on love, family, nature, and community life. Through music, stories and values are passed from one generation to the next.

Bicolano

The Bicolano people are the fourth-largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group. They make up 6.5 percent of the Philippine population and numbered 7,079,814 in the 2020 Philippines census. They are native to and still are largely found on the Bicol Peninsula and neighboring minor islands in southeast Luzon. Men from the region are often referred to as Bicolano, while Bicolana may be used to refer to women. They speak about a dozen closely related dialects of Bikol, largely differentiated according to cities, and closely related to other central Philippines languages. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Bicolano people are primarily farmers and live in rural areas. They produce rice, coconuts, hemp, and spices. The majority of Bicolanos are Roman Catholic, and many towns celebrate festivals in honor of patron saints. Catholic Mass is celebrated daily in many Bicol region churches. Minority Protestant and Muslim populations also exist among the Bicolano people. An undercurrent of animism persists as well. For instance, it is common for Bicolano people to believe that supernatural entities stalk houses and leave centavo coins as compensation.

Bicolanos live in the Bicol Region, which occupies the southeastern part of Luzon and contains the provinces of Albay, Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Catanduanes, Sorsogon, and Masbate. However, the majority of Masbate's population is a subgroup of Visayans. Many Bicolanos also live in the southeastern towns of the Calabarzon region and in Metro Manila. They also live outside of Luzon, particularly in Northern Samar in the Visayas (due to its proximity to Bicolandia) and in the Davao Region, Misamis Oriental, Caraga, and Soccsksargen regions of Mindanao.

According to the folk epic Ibalong, the people of the region were formerly called Ibalo or Ibalan, names believed to have been derived from Gat Ibal, who ruled Sawangan (now Legazpi City) in ancient times. Ibalong originally meant "people of Ibal," and eventually, this was shortened to Ibalon. The word Bikol, which replaced Ibalon, was originally bikod, meaning "meandering." This word supposedly described the main river in the area.

Bicolano Life, Religion and Culture

Copra processing and abacá fiber stripping, which are mostly done by hand in Bicol, and fishing are important livelihoods. Fish are especially abundant from May to September. Commercial fishing uses large nets and motorized boats called palakaya or basnigan, often equipped with electric lights. Small-scale fishermen use traditional nets such as basnig, pangki, chinchoro, buliche, and sarap. Other methods include fish corrals (bunuan) and hook-and-line tools like banwit, while mining—especially since the Spanish discovery of the Paracale mines—and abacá-based manufacturing are also important industries.

Most Bicolanos are Roman Catholics and celebrate the Feast of Our Lady of Peñafrancia every third Sunday of September in Naga City. The nine-day festival draws huge crowds of devotees who pray, light candles, and join processions. A highlight is the grand fluvial procession on the Naga River, where the image of the Virgin is carried by male devotees and accompanied by cheering crowds. The celebration also features cultural events such as shows, boat races, and other festivities. It is considered one of the largest Marian celebrations in Asia and is both a religious and cultural milestone for the Bicolano people.

The very active volcano Mount Mayon looms over much of Bicol. Before Spanish colonization, the Bikolanos practiced a complex polytheistic religion centered on powerful deities connected to nature. The supreme god was Gugurang, who lived inside Mount Mayon and guarded a sacred fire. When people committed sins, he caused the volcano to erupt as a warning. Ritual offerings called Atang were performed in his honor. His brother, Asuang, was an evil god who tried to steal the sacred fire and bring misfortune to humanity.

Several deities were linked to the moon and sea. Haliya was the masked goddess of moonlight and the protector of the moon god Bulan. She was the enemy of Bakunawa, a giant sea serpent believed to cause eclipses by trying to swallow the moon. Bulan, depicted as a beautiful young boy, was loved and pursued by Magindang, the god of the sea. According to legend, the movement of the waves symbolized Magindang’s attempt to reach Bulan, while Haliya repeatedly rescued him.

Other gods included Okot, the god of the forest and hunting. Bakunawa, the massive sea serpent, was feared as a devourer of the sun and moon and a major threat to cosmic balance. These myths explained natural events such as eclipses, volcanic eruptions, and ocean tides. Together, these deities formed a rich belief system that shaped early Bikolano understanding of the natural world.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026