AETA

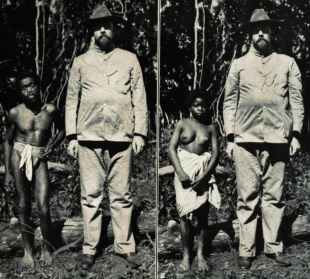

The Aeta are Negritos that live in the jungles and mountains of Luzon. They have traditionally lived by hunting and gathering food in the highlands and avoided mixing with people in the valleys and cities, where most Filipinos live, which they regard as a land of corruption. In the past many Aeta were illiterate and had few skills of value to lowlanders.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project in the early 2020s the Aeta Zambal Negrito population was 51,000 and Abellen Ayta was 6,500. There are thought to be about 60,000 Aeta. During the Vietnam War, Negritos taught Navy pilots jungle survival in the forest. Today they demonstrate jungle survival techniques at Subic Bay rainforest center.

Mining, deforestation, illegal logging, and slash-and-burn farming have severely reduced indigenous populations in the Philippines, leaving the Aeta today numbering only in the thousands. With limited protection from the government, the Aeta have become increasingly mobile, as social and economic pressures disrupt a way of life that had remained largely unchanged for thousands of years. [Source: Wikipedia]

Language: All Aeta communities have adopted the language of their Austronesian Filipino neighbors, which have sometimes diverged over time to become different languages.These include, in order of number of speakers, Mag-indi, Mag-antsi, Abellen, Ambala, and Mariveleño. The second languages they speak are Kapampangan, Ilocano, and Tagalog; Kapampangan in Central Luzon, Ilocano in Cagayan Valley and northern areas of Central Luzon, and Tagalog in Central Luzon, Southern Tagalog, and other areas of Luzon. [Source: Wikipedia]

Aeta Groups

Ambala Aeta – Zambales, Bataan

Abellen Aeta (also Abenlen, Abelling or Aburlin) – Tarlac

Magbukún Aeta (also Magbikin, Magbeken, or Bataan Ayta) – Bataan

Mag-antsi Aeta (also Mag-anchi or Magganchi) – Zambales, Tarlac, Pampanga

Mag-indi Aeta (also Maggindi) – Zambales, Pampanga

RELATED ARTICLES:

NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

AGTA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS) AND ORANG ASLI OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

See Sakai Under MINORITIES AND HILL TRIBES IN THAILAND factsanddetails.com

VEDDAS: THEIR HISTORY, LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

LIFE AND CULTURE OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND TRIBES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

Aeta Religion

Negritos are mostly animists but some have been converted to Christianity. Those that are animists have incorporated into their beliefs. According to the Christian group Joshua Project 5 to 10 percent of Aeta Zambal Negritos are Christian and 2 to 5 percent are Protestant Evangelicals. Among Abellen Ayta 10 to 50 percent are Christians and 2 to 5 percent are Protestant Evangelicals.

There are differing views regarding the dominant character of Negrito religious beliefs. Those who consider them monotheistic argue that various Negrito groups believe in a supreme being who rules over lesser spirits or deities, such as the Aeta of Mount Pinatubo, who venerate Apo Na. At the same time, Negrito belief systems are strongly animistic. For example, the Aeta of Pinatubo believe that spirits inhabit the natural environment, including rivers, seas, the sky, mountains, hills, valleys, and other places. One such spirit, Kamana, the forest spirit, is believed to appear and disappear, offering comfort and hope during times of hardship. [Source: Wikipedia]

Prayer among the Negritos is not confined to special occasions but is closely linked to daily economic activities. Ritual dances are performed before and after pig hunts, while on the night before women gather shellfish, they perform dances that serve both as an apology to the fish and as a charm to ensure a successful catch. Similarly, men conduct a bee dance before and after honey-gathering expeditions.

Within Negrito indigenous polytheistic traditions, the “Great Creator” is understood to manifest in four aspects. Tigbalog is associated with life and action, Lueve with production and growth, Amas with compassion, love, unity, and inner peace, and Binangewan with change, sickness, and death. Collectively, these manifestations are known as Gutugutumakkan, the supreme being and great creator. Other important deities include Kedes, the god of the hunt; Pawi, the god of the forest; and Sedsed, the god of the sea. Among certain Negrito groups, Apo Namalyari and Bapan Namalyari are also revered as gods of creation.

Christianity reached the Aeta communities in the mid-1960s through missionaries from the American-based Evangelical Protestant group New Tribes Mission, which sought to bring Christian teachings to Philippine tribal groups. The mission emphasized education and pastoral training for indigenous converts so they could minister within their own communities. Today, a significant number of Negritos in Zambales and Pampanga identify as Evangelical Christians, and some have also joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Aeta Life

Most Aeta live in villages in thatch roof huts and keep livestock such as water buffalo, pigs and chickens. In the past and maybe to some degree now they hunted wild boar, deer, mountain cats and a variety of birds, collected fish, electric eels and fresh-water shrimp from streams, and grew mountain rice, sweet potatoes, bananas, beans and other root crops.

Aeta men used to wear loincloths, young women wore sarongs (wrap around skirts) and elder women wore and elder women wear bark cloth. Today, most Aeta who have been in contact with lowlanders and mainly wear T-shirts, pants and rubber flip flops.

The Aetas are skilled at weaving and plaiting. Women exclusively weave winnows and mats. Only men make armlets. They also produce raincoats made of palm leaves that surround the neck and spread out like a fan around the body.

Aeta Hunter-Gatherer Lifestyle

The Aeta were traditionally nomadic, constructing temporary shelters made of sticks driven into the ground and roofed with palm or banana leaves. More recently, many Aeta have settled in villages or in cleared mountain areas, where they live in more permanent houses built from bamboo and cogon grass. [Source: Wikipedia]

As hunter-gatherers, adaptation is central to Aeta survival. This includes detailed knowledge of the tropical forests they inhabit, seasonal weather patterns, typhoon cycles, and how these factors influence plant and animal behavior. Storytelling is another vital survival skill. Through stories, the Aeta pass on knowledge and reinforce social values such as cooperation, and skilled storytellers are therefore highly respected within the community.

The dry season is a period of especially intense labor for many Aeta communities. Hunting and fishing increase, and land is cleared through swidden farming in preparation for future harvests. Although both men and women participate in clearing fields, women typically carry out most of the harvesting. During this time, the Aeta also engage in trade and wage labor with nearby non-Aeta communities, selling gathered food or working as temporary farmers and field laborers. Aeta women play particularly active roles in these exchanges, often acting as traders or agricultural workers for lowland farmers. In contrast, the rainy season—usually from September to December—often brings food shortages due to the difficulty of hunting and gathering in flooded and muddy forests.

Aeta Hunting

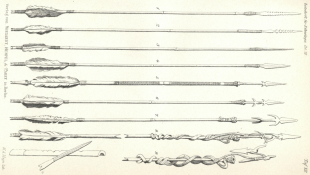

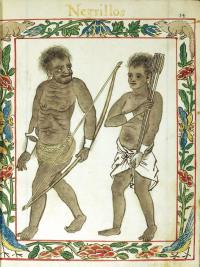

Aeta communities use a variety of tools for hunting and gathering, including traps, knives, and bows and arrows fitted with different types of arrowheads for specific purposes. Most Aeta, including women, are trained in hunting and gathering by the age of fifteen. While men and some women commonly use bows and arrows, many Aeta women prefer knives and often hunt in groups with dogs to improve efficiency and strengthen social bonds. Fishing and food gathering are shared tasks among both men and women, reflecting the generally egalitarian social structure of Aeta communities.

Aeta used to hunt with bows and arrows, with arrows that had different points depending on which kind of animal they were pursuing. There were ones for bird, ones for lizards and elaborate one for wild boars. One unusual thing they liked to do was smoke cigarettes with the lighted ends in their mouths.

The Aeta still regard wild animals as delicacies, with flying fox considered a choice delicacy. When preparing the one kilogram bats Negritos first singe the hair, which also gets rid of a musky oil that permeates the hair, and then they roast the animals whole on a stick. Negritos like the intestines. One writer who tried a breast quarter said it "proved delicious—lean, dry and flavorful." Flying foxes in the Philippines are easily disturbed. Negritos approach them with banana leaves on their heads which seems to make the animals feel relaxed.

According to a 1975 study, "About 85 percent of Philippine Aeta women hunt, and they hunt the same quarry as men. Aeta women hunt in groups and with dogs, and have a 31 percent success rate as opposed to 17 percent for men. Their rates are even better when they combine forces with men: mixed hunting groups have a full 41 percent success rate among the Aeta." [Source: Frances Dahlberg, “Woman the Gatherer,” Yale University Press, 1975]

Aeta Society

In Aeta society, the father is usually seen as the head of the family, but traditionally there is no formal political authority. Aeta communities do not appoint chiefs, and all individuals are considered equal. Social order is guided by custom and tradition rather than written laws, and these traditions help maintain equality and shape daily life. [Source: Wikipedia]

When disputes or important matters arise, the community turns to a group of respected elders known as the pisen. These elders help discuss and guide decisions, but their role is advisory only. No one is forced to follow their recommendations. Conflict resolution depends on open and repeated discussion, with the goal of reaching understanding rather than imposing authority.

Over time, contact with lowland Filipino society disrupted this egalitarian system. Government officials and outsiders sometimes pressured Aeta communities to adopt formal political structures similar to those in the lowlands. In some cases, Aeta groups temporarily organized with positions such as captain, council, or police, but many resisted these arrangements. They strongly opposed appointing a chief or president, even though one elder might informally assume leadership responsibilities.

This informal system also applies to justice within the community. When someone commits a wrongdoing, elders and adult men deliberate to understand the reasons behind the act and to prevent further harm, rather than deciding on punishment. Young people are excluded from these discussions, and women generally have limited roles in decision-making. Although women may attend hearings or voice opinions, traditional gender roles usually confine them to childcare and household responsibilities, reducing their influence in community decisions.

Aeta Medicine

The Aeta take pride in their reliance on herbal medicine, which is closely tied to their natural environment. By sourcing remedies directly from their surroundings rather than depending on purchased medicines, they reinforce a strong relationship with nature. This approach not only preserves cultural knowledge but also reflects sustainable healthcare practices grounded in respect for the environment. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Aeta community in Ilagan, Isabela practices an extensive system of traditional herbal medicine to treat common illnesses and support overall well-being. Various plants are used for specific conditions, such as banana leaves for toothaches, camphor leaves for fever and colds, kalulong leaves for muscle pain, and sahagubit roots for postpartum care, deworming, and stomach ailments. Other remedies address birth control, menstrual irregularities, and blood pressure, while certain plants are deliberately avoided due to beliefs about their potential harmful effects.

If an illness does not improve after repeated use of herbal treatments, the Aeta believe the cause may be spiritual rather than physical. In such cases, they seek the help of a herbolario, or ritual healer, who performs a diagnostic and healing ceremony known as ud-udung. This ritual involves identifying the offended spirit and restoring balance through cleansing practices and food offerings.

Aeta Culture and Art

Body scarification is a traditional form of visual art. The Aetas intentionally wound the skin on their backs, arms, breasts, legs, hands, calves, and abdomen. Then, they irritate the wounds with fire, lime, and other methods to form scars. Other "decorative disfigurements" include chipping teeth. The Dumagat modify their teeth with a file during late puberty. They dye their teeth black a few years later. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Aetas generally use ornaments typical of people living in subsistence economies. Flowers and leaves are used as earplugs for certain occasions. They frequently wear girdles, necklaces, and neckbands of braided rattan with wild pig bristles.

The Aeta have a musical heritage consisting of various types of agung ensembles. These ensembles are composed of large, hanging, suspended, or held bossed or knobbed gongs that act as drones without any accompanying melodic instruments.

Aeta and Mt, Pinatubo

Many Aeta live or lived around Mt. Pinatubo, the volcano that erupted violently in 1991. Traditionally, the Aeta sacrificed a pig with a bottle of gin into the volcano’s crater to placate Apo Malyari, the mountain god of Mt, Pinatubo and keep who live and work around the volcano safe. Apo Malyari is regarded as a combination of smoke, fire and earthquakes. According to legend he was unjustly trapped by lava under Pinatubo and escapes ever 400 or 500 years with great eruption.

Hundreds of Aeta died during and after the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. Some of them died in the eruption itself. Others starved from a lack a food. Some of those who resettled in evacuation camps died of measles and other lowland diseases for which they had no immunity. Most of those that remained or were left behind in the villages died. Many who chose to hide out in caves rather than evacuate also died. The survivors were mainly those who evacuated far enough to get out of harms way.

The way of life of Aeta was dramatically changed after the eruption. The villages where they used to live are under meters of ash; trees that provided shade from the hot sun are gone; and their hunting grounds were closed. Many moved back to the mountain and grew what crops they could. The sandy soil made that difficult. Mountain rice turned yellow and withered when planted in the ash. Banana trees were about the only food sources that did well. But the Aeta complained they couldn’t live on bananas alone.

Many Aeta remained in evacuation centers that looked like refugee camps. In the 1990s they wore Western cloths, worked as laborers, collected banana blossoms and bartered the for rice, and attended classes that aimed to teach them how to make handicrafts.

Pressures on the Pinatubo Aetas

Deforestation and development have fragmented the forest territories of the Pinatubo Aetas and pushed their traditional way of life toward collapse. Many of their languages are close to extinction, and essential survival skills are fading. Edward Serrano, an Aeta survival instructor, told AFP: “We can no longer do many of the things that our ancestors took for granted.” The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo exacerbated these pressures. [Source: Cecil Morella, AFP, August 7, 2015]

Serrano’s village of Sapang Uwak, or “Crow Creek,” illustrates both cultural continuity and disruption. The community still relies on farming bananas and taro and uses water buffalo for transport, yet villagers must pass through a massive private entertainment park just to reach markets or find work. Although the Aetas claim the surrounding land as ancestral domain, development has encroached on their daily lives. What was once a continuous forest landscape has become a patchwork of restricted spaces. This isolation undermines their nomadic traditions and food security.

A 1997 law formally recognized the ancestral land rights of around 15 million ethnic minorities, including the Aetas. Sapang Uwak and nearby communities have filed claims covering about 17,000 hectares, but many boundaries remain undefined. Roman King, an Aeta leader, voices deep frustration, saying, “We were the first peoples of the Philippines, but now we are aliens in our own country.” He warns that without secure land, displacement and urban poverty will worsen. The slow pace of government action has left communities vulnerable to private developers.

Nationwide, progress on land titles has been limited and uneven. Only 180 ancestral domain titles have been issued, while millions of claims remain unresolved. Although ancestral lands are legally protected from sale, outsiders often acquire them through coercion or manipulation. Anthropologist Cynthia Zayas notes that “Private developers are eating up their land,” adding that Aetas risk becoming “squatters in their own land.” Even where titles are secured, the process takes years and demands legal knowledge many communities lack.

The aftermath of the Pinatubo eruption further destabilized Aeta society. Around 35,000 Aetas were displaced to shelters near towns, where many families became dependent on begging. Exposure to lowland lifestyles brought processed foods and new illnesses, including diabetes and hypertension. While education and integration are promoted as solutions, officials acknowledge this means abandoning a roaming life. As one observer notes, survival now depends on balancing cultural identity with adaptation to an unforgiving modern world.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026