NEGRITOS

The Negritos are a dark skinned people that are ethnically different from other people in the Philippines that are mostly Malay in origins. The are believed to be the original inhabitants of the Philippines. Their origins are obscure. Some anthologist believe they are descendant of wandering people that "formed an ancient human bridge between Africa and Australia."

The Negritos of the Philippines, along with the Semang Negritos of peninsular Malaysia, are believed to survivors of the original hunter gathers that inhabited Southeast Asia and the Pacific before the arrival of the Chinese and Malays. Some Negritos adopted the Chinese language. They are regarded as the ancestors of the hunter-gatherers that live on New Guinea and the Solomon Islands and other Pacific islands. Philippine Negritos have genetic links to East Asian groups, prehistoric Hoabinhian populations, and Indigenous peoples of New Guinea and Australia, with whom they share a Denisovan genetic admixture. [Source: Wikipedia]

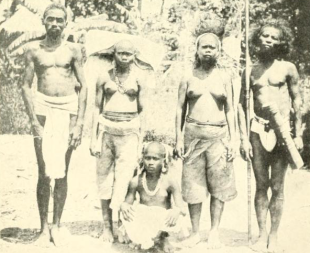

The Negritos of the Philippines are often considered a single group, but in actually they are composed of 25 to 35 widely scattered ethno linguistic groups that share similar hunter-gatherer lifestyles and physical features and collectively totally about 51,000 people. Also known as the Aeta, Atta, Baluga, Ayta, Áitâ," Ita, Alta, Arta, Batak, Dumagat, Mamanwa, Pugut,, they mainly live in the mountains of Luzon.. but can also be found in other places in he Philippines. The main Negrito groups are the Aeta are from Central Luzon, the Agta are from Southeastern Luzon, and the Dumagat (also spelled Dumaget) from Eastern Luzon. However, these divisions are arbitrary, and the three names can be used interchangeably. The Aeta are also commonly confused with the Ati people of the Visayas Islands and Panay, Negros, Cebu and Mindanao. . [Source: Thomas N. Headland, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

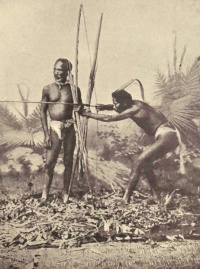

Negritos have dark skin, kinky “peppercorn” hair and little body hair and are small in size. Among the Agta groups men average 153 centimeters (60 inches) and 45 kilograms (99 pounds) and women average 144 centimeters (56 inches) and 38 kilograms (84 pounds). Although they are linked more closely genetically to Asians than Africans, their appearance and traditional lifestyles are similar to that of the Pygmies of Africa.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AETA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, LIFE, HUNTING, HEALTH factsanddetails.com

AGTA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

SEMANG (NEGRITOS) AND ORANG ASLI OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

See Sakai Under MINORITIES AND HILL TRIBES IN THAILAND factsanddetails.com

VEDDAS: THEIR HISTORY, LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

LIFE AND CULTURE OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLAND TRIBES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

History of Negritos

Modern humans first reached the Philippines during the Paleolithic period as early as 70,000 years ago, followed by additional migration waves between 25,000 and 12,000 years ago from Asia via Sundaland land bridges when glacial peaks during the Ice Age lowerered sea levels. It is believed some of these peoples were descendants of Negritos. A later migration, associated with Austronesian peoples from Taiwan about 7,000 years ago, are linked the Malay people that dominate modern Philippines. [Source: Wikipedia]

In 2010, a team of archaeologists has confirmed that a foot bone they discovered in Callao Cave in Cagayan province is at least 67,000 years old, older than the so-called Tabon Man of Palawan, which has long been thought to be the archipelago’s earliest human remains at 50,000 years old, a report on GMANews. Archeological remains have been found in several caves, some used for dwellings, and other as burial sites in present-day Malaysia. The oldest remains were found in Lang Rongrien cave dating 38,000 to 27,000 years before present, and in the contemporary Moh Khiew cave. The indigenous groups on the peninsula can be divided into three ethnicities, the Negritos, the Senois, and the proto-Malays. The first inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula were most probably Negritos. It is plausible that Negritos of the Philippines could have descended from them.

Negritos resemble other dark skinned people from Africa and Australia, but it turns their genetic affinities are much more similar to the people around them. This suggests that Negritos and Asians had the same ancestors but that Negritos developed feature similar to Africans independently or that Asians were much darker and developed lighter skin and Asian features, or both.

Scholars almost universally reject the theory that their ancestors came form Africa. Rather it is believed they are descendants of an ancient group of humans who migrated to the Philippines from mainland Southeast Asia around 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, in the Upper Pleistocene period when an Ice Age caused the sea levels to drop and made the Philippines easier to get to. They developed their physical characteristics where they lived through a process of microeveolution that began around 25,000 years ago. Later they began mixing with Austronesian-speaking people that began arriving around 3000 B.C., most likely from Taiwan.

The population of Negritos has declined since the arrival of the Spanish around 1600. Their population continues to decline as a result of high death rates caused by encroachment of outsiders, deforestation, depletion of traditional game and food sources, poverty, disease and volcanic eruptions. In some cases they have been herded onto small reservations by the government and their culture is under sharp attack.

Negrito Groups in the Philippines

Aeta – Central Luzon

Ambala Aeta – Zambales, Bataan

Abellen Aeta (also Abenlen, Abelling or Aburlin) – Tarlac

Magbukún Aeta (also Magbikin, Magbeken, or Bataan Ayta) – Bataan

Mag-antsi Aeta (also Mag-anchi or Magganchi) – Zambales, Tarlac, Pampanga

Mag-indi Aeta (also Maggindi) – Zambales, Pampanga

[Source: Wikipedia]

Agta – Southeastern Luzon

Alabat Agta (also Alabat Island Agta) – Quezon

Agta Cimarron – Camarines Sur

Manide (also Abiyan Agta or Camarines Norte Agta) – Camarines Norte, Quezon

Rinconada Agta (also Iriga Agta) – Camarines Sur

Tabangnon (also Partido Agta, Katabangan, Katubung, or Isarog Agta) – Sorsogon, Quezon, Camarines Sur

Dumagat – Eastern Luzon

Alta

Northern Alta – Aurora

Southern Alta (also Kabulowan Alta or Edimala) – Quezon, Nueva Ecija

Arta – Quirino

Atta

Faire-Rizal Atta – Cagayan province

Pamplona Atta – Cagayan province

Pudtol Atta – Cagayan province

Casiguran Dumagat – Aurora

Central Cagayan Dumagat – Cagayan

Palanan Dumagat – Isabela

Paranan Dumagat (or Pahanan Dumagat) – Isabela

Disabungan Dumagat – Isabela

Dupaningan Dumagat – Cagayan

Madella Dumagat – Quirino

Sinauna Tagalog (also Remontado Dumagat) – Rizal, Quezon

Umiray Dumagat – Quezon, Aurora

According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 900 Casiguran Dumagat in the early 2020s.

Negrito groups found on Philippines island other than Luzon are 1) the Ati, the indigenous peoples in the Visayan Islands, found mainly on the islands of Boracay, Panay and Negros; 2) the Batak of Palawan and 3) the Mamanwa of Mindanao.

Philippines Negrito Religions

All Philippine Negritos traditionally practice animism. Today, most remain animists, though some of their beliefs have been influenced by Roman Catholicism. According to the Christian group Joshua Project most Dumagat practice traditional animist religions and 2 to 5 percent of Casiguran Dumagat Agta are Christians, with 0.1 to 2 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. [Source: Encyclopedia of Religion, Thomson Gale, 2005]

A notable feature of Negrito religion is its lack of systematization. Consequently, religion plays a secondary role in Negrito ideology. The sporadic and individualistic nature of the animistic beliefs and practices of Philippine Negritos means they exert less control over people's daily lives than the religious systems of other animistic societies in the Philippines. Similarly, the minor role of religion in most Philippine Negrito cultures contrasts with the significant religious practices of the Negritos of Malaysia, as reported by Kirk Endicott in Batek Negrito Religion (Oxford, 1979).

Nevertheless, Philippine Negritos universally believe in a spirit world containing many classes of supernatural beings. These beings are believed to influence processes of nature, as well as the health and economic success of humans. The Negritos are especially preoccupied with the malignant ghosts of deceased humans. Most Negritos also believe in a supreme deity. Scholars have debated whether this "monotheism" is of pre-Hispanic origin or merely the result of Christian influences.

Philippines Negrito Culture

All Negrito groups speak Austronesian languages. All the native languages of the Philippines are Austronesian languages. The languages the Negritos speak are usually more closely related to the languages of people that live around them than they are to the languages of other Negrito groups. Most are bilingual, speaking their own language and the language of their non-Negrito neighbors.

Negritos have traditionally gotten almost everything they need from the rain forest and never evolved agriculture. Negritos have traditionally lived on of hunting, gathering, fishing, marginal cultivation and symbiotic relationships with neighboring non-Negrito people. Some live in the forest lean-tos made from sticks and grasses and make clothes from the inner bark of trees. Most live in villages.

Negrito girls and boys of Northern Camarines and part of Quezon blacken their teeth to look attractive. Also in the Northern Camarines and throughout the former Tayabas, boys and girls had their noses bored before marriage and wore a nose-stick after that. [Source: Teresita R. Infante, kasal.com]

As is also true with the pygmies in Africa, Negritos often trade forest products for cash or starch foods like rice or corn. They also serve as guides and work as laborers on nearby farms. This symbiotic elation has been going for some time. Based largely on linguistic similarities between Negritos and non-Negritos, it is estimated that many Negrito groups gave up complete hunting and gathering around 1000 B.C. and have been trading and interacting with non-Negritos since then.

Aeta

The Aeta are Negritos that live in the jungles and mountains of Luzon. They have traditionally lived by hunting and gathering food in the highlands and avoided mixing with people in the valleys and cities, where most Filipinos live, which they regard as a land of corruption.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project in the early 2020s the Aeta Zambal Negrito population was 51,000 and Abellen Ayta was 6,500. There are thought to be about 60,000 Aeta. During the Vietnam War, Negritos taught Navy pilots jungle survival in the forest. Today they demonstrate jungle survival techniques at Subic Bay rainforest center.

Most Aeta live in villages in thatch roof huts and keep livestock such as water buffalo, pigs and chickens. In the past and maybe to some degree now they hunted wild boar, deer, mountain cats and a variety of birds, collected fish, electric eels and fresh-water shrimp from streams, and grew mountain rice, sweet potatoes, bananas, beans and other root crops.

Men used to wear loincloths and women, sarongs. Many hunted with bows and arrows, with arrows that had different points depending on which kind of animal they were pursuing. There were ones for bird, ones for lizards and elaborate one for wild boars. One unusual thing they liked to do was smoke cigarettes with the lighted ends in their mouths.

See Separate Article: AETA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, LIFE, HUNTING, HEALTH factsanddetails.com

Agta

The Agta are a group of Negritos that live in a widely scattered areas of eastern Luzon. Also known as the Alta, Arta, Baluga, Dumagat, Negritos, and Pugut, they have traditionally been hunters and gatherers and live along the eastern coast of Luzon in Cagayan, Isabela, Aurora, Quirino, Quezon, Camarines Norte, and Camarines Sur provinces, between 14° and 19° N and 121° and 123° E. [Source: Thomas N. Headland, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

They areas were they live were once 90 percent covered by dipterocarp tropical lowland forest. These areas have now largely been deforested. By the 1980s, only about 40 percent of the area was covered by primary forest, while another 20 percent was covered by secondary forest. The remaining area was grassland (13 percent), brushland (11 percent), or farmland (16 percent). The recent acceleration of deforestation is the result of commercial logging and an influx of colonist farmers from other areas of Luzon. The area is classified as a true rainforest with an average annual rainfall ranging from 361.8 centimeters in the deforested flatlands to 712.5 centimeters in the mountainous forests. The mean annual temperature is 26°C, and the mean relative humidity is 87%. There is no pronounced dry season. ~

In the 1990s the Agta were divided into eight ethnolinguistic groups, numbering in total about 7,000 people. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 2,000 Dupaninan Agta, an unknown number of Alabat Island Agta, 1,400 Katubung Agta and 3,700 Mt. Iriga Agta in the early 2020s.

See Separate Article: AGTA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, FOOD factsanddetails.com

Batak of Palawan

The Batak are a Negrito group that lives in northeastern Palawan. Also called Tinitianes and not to be confused with Batak of Sumatra, Indonesia, they numbered 1,531 in the 2020 Philippines census and 3,900 in a Joshua Project tally in the early 2020s. They are related to the Aeta on Luzon and similar groups in Indonesia.

The Batak have long combined a hunting-and-gathering with the seeding of useful food plants, kaingin (slash-and-burn cultivation), and trade. For centuries, they maintained important commercial ties with maritime peoples of the Sulu region, exchanging forest and natural products for manufactured goods. Beginning around 1900, Filipino settlers and other migrants moved into the Batak’s traditional territories, leading to the gradual loss of Batak land and resources. In the 1930s, the government attempted to create Batak reservations in the coastal plains, but these areas were soon occupied and overwhelmed by Filipino migrants during the 1950s, forcing the Batak to retreat inland into the island’s interior. [Source: Wikipedia]

By the mid to late twentieth century, emigrant farmers—mostly from Luzon—had pushed the Batak from their preferred coastal gathering areas into the mountains. Residing in less fertile environments, the Batak sought to supplement their livelihoods by collecting and selling various non-timber forest products, including rattan, tree resins, and honey.

Some Batak practice small-scale cultivation of rice, corn, sweet potato, and cassava. Some sell and trade rattan, honey, and Manila copal in exchange for rice, clothing materials, and other basic goods. Wage labor plays a significant role in the Batak economy, with men commonly hired for short periods to perform tasks such as weeding, harvesting, or picking coconuts and coffee. In recent years, local tourism has also become an additional source of income for the Batak.

Batak Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project Most Batak follow traditional animist religions and 5 to 10 percent are Christians, 0.1 to 2 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. The Batak belief system is rooted in animism, the belief that spirits inhabit the natural world. These spirits are generally classified into two groups: the Panya’en, which are considered malevolent or dangerous, and the Diwata, which are usually benevolent but can also be unpredictable. To maintain harmony with the spirit world, the Batak regularly make offerings, and shamans (babaylan) play a central role in religious life. Through rituals and spiritual possession, shamans communicate with spirits and are believed to have the power to heal the sick.

Among the Batak deities, Maguimba is regarded as a primordial god who once lived among the people after being summoned by a powerful shaman. He provided all necessities of life, possessed cures for all illnesses, and even had the ability to bring the dead back to life. Diwata is a benevolent deity who provides for both women and men and grants rewards for good deeds.

Angoro resides in Basad, a realm beyond the human world, where the souls of the dead are judged and either admitted into the heavens known as Lampanag or cast into the depths of Basad. Other deities associated with strength include Siabuanan, Bankakah, Paraen, Buengelen, and Baybayen.

The Batak also recognize numerous nature spirits tied to specific elements of the environment. Batungbayanin is the spirit of the mountains, Paglimusan dwells in small stones, Balungbunganin inhabits almaciga trees, and Sulingbunganin resides in large rocks. An ancestral figure, Esa’, is believed to have shaped the landscape during a hunting journey with his dogs, naming places as he pursued wild pigs. Agricultural and natural resources are governed by deities such as Baybay, the goddess and master of rice, and her husband Ungaw, the god and master of bees; both originated from Gunay Gunay, the edge of the universe. The Panya’en are mystic entities that control certain wild trees and animals, including Kiudalan and Napantaran, who are specifically associated with forest pigs.

Batak Life and Culture

The Batak were once a nomadic people, but under government direction they have since settled in small, permanent villages. Despite this shift, they continue to undertake short forest-gathering trips lasting several days, an activity that remains important both economically and spiritually.

Cultural disruption has severely affected the Batak as a result of rapid population decline, restricted access to forests, enforced sedentary living, and the encroachment of immigrant settlers. Today, marriages between Batak are uncommon, with most individuals marrying into neighboring groups. Children from these unions often do not follow traditional Batak ways, making “pure” Batak increasingly rare. Low reproduction rates have further weakened population continuity. Consequently, the Batak are gradually being absorbed into a broader upland indigenous population that is itself losing distinct tribal identities, along with unique cultural practices and spiritual traditions. There is ongoing debate over whether the Batak continue to exist as a distinct ethnic group.

Batak families trace descent bilaterally, recognizing kinship through both the maternal and paternal lines, in a manner similar to other Filipino groups. Because individuals are discouraged from using the birth names of their in-laws, Batak often have multiple personal names. Divorce and remarriage were once common and socially accepted, though increased integration into mainstream Filipino society has altered these practices to some extent.

Husbands and wives generally enjoy equal freedoms, although women typically move into their husband’s household, except during the early stages of marriage when the couple may reside with the wife’s family. The nuclear household serves as the primary economic unit, though several households may pool resources when necessary. Even so, each household is expected to be largely self-sufficient. Batak families tend to be small, averaging about 3.5 members per household.

Traditionally, the Batak diet consisted of squirrels, jungle fowl, wild pigs, honey, fruits, yams, fish, mollusks, crustaceans, and other forest-sourced foods. These resources were primarily obtained from the surrounding forests. To hunt animals, especially wild pigs, the Batak employed various techniques, including bows and arrows, spears, dogs, and later, homemade firearms, with hunting methods evolving over time as outside influences increased.

Ati of the Visayan Islands

The Ati are a Negrito group and the indigenous peoples of the Visayan Islands, Found principally on the islands of Boracay, Panay and Negros, they are genetically related to other Negrito ethnic groups in the Philippines such as the Aeta, Batak, Agta and Mamanwa of Mindanao.According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Ati Negrito population in the late 2020s was 13,000. The Ati speak a distinct language known as Inati, which had about 1,500 speakers according to a 1980 census. Many Ati also speak Hiligaynon and Kinaray-a, reflecting long-standing contact with neighboring populations. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project]

The Philippine legend of the Ten Bornean Datus recounts the arrival of Bisaya ancestors in Panay in the early 12th century after fleeing persecution in Borneo. According to the legend, land was peacefully exchanged with Ati leaders, leaving the uplands to the Ati and the lowlands to the newcomers. This event is commemorated in the Ati-atihan festival, though historians debate the historical accuracy of the account.

Traditionally nomadic, the Ati of Panay were considered the most mobile among Negrito groups. In recent times, most have settled in permanent communities in places such as Barotac Viejo, Guimaras Island, Igkaputol (Dao), Tina (Hamtic), and Badiang (San Jose de Buenavista). Today, only a small number of Ati remain semi-nomadic, mainly women with young children. Ati men often engage in seasonal labor as sacadas during sugarcane harvests in areas such as Negros and Batangas.

The Ati were the original inhabitants of Boracay Island. Boracay Island remains central to Ati identity and is regarded as ancestral land, particularly the area of Takbuyan along the island’s southwestern coast. As tourism expanded, many were displaced, losing their ancestral lands and homes and relocating largely to the mainland in Caticlan. During the 2018 closure and redevelopment of Boracay, government land reform initiatives resulted in the awarding of land titles totaling 3.2 hectares to Ati families—about one percent of the island’s total area. Despite this progress, the Ati of Boracay continue to face challenges related to limited access to education and persistent discrimination.

Ati Religion and Culture

According to Joshua Project most Ati practice traditional animist religions and 5 to 10 percent are Christian, with 0.1 to 2 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. Traditional Ati religious beliefs and center on the existence of both benevolent and malevolent spirits associated with nature. These spirits are believed to inhabit rivers, the sea, the sky, and the mountains, where they may either cause illness or provide protection and comfort. Among the Ati of Negros, such spirits are called taglugar or tagapuyo, meaning “those who inhabit a place.” Over time, Christianity has been adopted, largely due to reduced isolation and increased interaction with outsiders. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project]

The Ati are well known in Panay for their knowledge of herbal medicine. Local residents frequently seek their assistance, especially for traditional treatments such as removing leeches from the body. In the past, Ati clothing was simple and similar to that of other Negrito groups, with women wearing wraparound skirts—sometimes made from bark cloth—and men wearing loincloths. Today, everyday attire commonly consists of T-shirts, pants, and rubber sandals. Jewelry remains modest, often crafted from natural materials such as flowers, plant fibers, and animal bones, particularly pig teeth.

The Ati are the focal point of the Ati-atihan Festival, which is held in their honor and is believed to commemorate the early arrival of Spanish missionaries and the Roman Catholic Church in Aklan. Oral tradition holds that the Ati assisted the Spaniards in subduing the Visayans and were rewarded with a statue of the Santo Niño. In Iloilo City, the Dinagyang Festival similarly features performers painted to resemble Ati and organized into “tribes” (tribus) that perform drum-accompanied dances. The festival celebrates both the legendary purchase of Panay from the Ati and the arrival of the Santo Niño image in Iloilo in 1967, an event marked by the participation of a tribe from the Ati-atihan Festival.

Mamanwa of Mindanao

The Mamanwa people are one of the oldest tribes in the Philippines. Also spelled and known as Mamanoa, Conking, Mamaw, Amamanusa, Manmanua and Mamaua, they were previously believed to be a subgroup of the Luzon Negritos, but after numerous physical anthropological studies, they are now believed to be distinct from them. They live in Agusan del Norte, Surigao del Norte and Surigao del Sur provinces in northeastern Mindanao and Panaoan Island and Southern Leyte. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Mamanwa Negrito population in the late 2020s was 9,900. According to Wikipedia there were approximately 5,000 speakers of the Mamanwa language in 1990.[Source: Joshua Project, Ethnic Groups of Philippines, California State University, East Bay]

Physically, the Mamanwa share traits common among Negrito peoples, including dark skin, small stature, curly hair, and black eyes. Most are small, standing between 1.35 and 1.5 meters tall. The name Mamanwa comes from the words man, meaning “first,” and banwa, meaning “forest,” together translated as “first forest dwellers.” Before the Mamanwa settled in central Samar Island, an earlier Negrito group known as the Samar Agta is believed to have lived there. With the arrival of the Mamanwa, the Samar Agta reportedly shifted to speaking Waray-Waray, or Northern Samarenyo, and may have partially integrated with the Mamanwa community.

Like other Negrito groups, the Mamanwa adopted the language of a nearby dominant population. They are found mainly in the areas of Kitcharao and Santiago, though they remain highly mobile and frequently relocate. As hunting has declined in importance, traditional tools such as the bow and arrow have largely fallen out of use. The Mamanwa now obtain part of their subsistence through labor arrangements with neighboring groups. Their settlements typically consist of three to twenty households arranged in a circular pattern on high ridges or in valleys, with houses that generally lack walls. Communities are organized around kinship, and leadership is usually held by the oldest and most respected male.

The Mamanwa are notable for preserving their cultural identity through the protection of their ancestral lands, a practice they share with the Manobo tribe. Together, they established the Mamanwa–Manobo Indigenous Community Conserved Area (ICCA), which safeguards forested mountain regions known as Binantazan nga Banwa and Binantajan nu Bubungan, meaning “protected forested mountains.” These protected areas cover about 1,546.5 hectares, consisting mostly of primary dipterocarp forest with a smaller area of secondary forest.

At the heart of this conserved landscape is Mount Panlabao, the highest and most sacred peak within the ancestral domain. Regarded as deeply significant and vulnerable to harm, the mountain is believed to be guarded by spirit dwellers. Both the Mamanwa and Manobo conduct rituals before approaching its sacred areas, reflecting their shared reverence for the site and their commitment to its protection.

Mamanwa Life and Society

Although hunting once played a central role in their culture, this practice has gradually diminished. Today, they rely more on bayatik (spear traps) and gahong (pit traps) to capture animals, while supplementing their diet with wild fruits, nuts, honey, and occasionally python meat. In addition, they engage in wage labor with nearby groups and produce woven items such as baskets and hammocks for use or trade. [Source: Joshua Project, Ethnic Groups of Philippines, California State University, East Bay]

The nomadic, mountain-dwelling Mamanwa live in small communal settlements typically made up of three to twenty households, situated either on high ridges or deep within valleys. This pattern of settlement is not entirely voluntary, as many Mamanwa have been pushed into remote hinterlands by the expansion of heavy industries into their ancestral areas. Despite these pressures, they continue to practice and preserve many of their distinctive customs and traditions.

Community leadership rests with the oldest and most respected men, who are responsible for settling disputes and guiding communal affairs. Elders are held in especially high regard, as they maintain peace and order within the group and exercise authority over judicial matters. Leadership is informal and cannot be passed on to close relatives, reflecting the Mamanwa’s generally frank disposition, aversion to the pursuit of power, and strong preference for harmony. Their socio-political system is therefore based more on respect and consensus than on rigid structures.

Because Mamanwa territories are often shared or frequented by other tribal groups, intermarriage is common. This interaction has led to the blending of socio-political systems, religious practices, and cultural beliefs. A notable example is the shared belief in a supreme being called Magbabaya, recognized by both the Mamanwa and the Manobo. This belief also encompasses reverence for spirits, unseen beings, and environmental guardians, who are treated with great respect to avoid misfortune or calamity. Such integration extends to language as well, with the dialects of the two groups being mutually understood.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026