IFUGAO

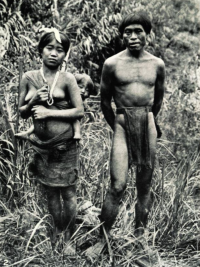

The Ifugao is a group that lives in a mountainous region of north-central Luzon around the of town Banaue. Also known as the Ifugaw, Ipugao, Yfugao, Igorot and Kiangan, they are famous for their spectacular mountain-hugging rice terraces and are believed to have arrived in their homeland from China around 2000 years ago. Their first main contact with the outside world was through American military officers and schoolteachers early in the 20th century. Communication with them was made easier when better roads were built to the areas where they live. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

In the past the Ifugao were feared head-hunters, just as other tribes in the mountainous regions of northern Luzon. Their war-dance (the bangibang) is one of the cultural remnants of the time of tribal conflict. This dance is traditionally held on the walls of the rice terraces by the men, equipped with spears, axes and wooden shields and a headdress made of leaves. [Source: philippines.hvu.nl]

Ifugao (pronunced EE-foo-gow) means "inhabitant of the known world." It comes from the term ipugo, meaning “earth people,” “mortals,” or “humans,” as distinct from spirits and deities. It can also be interpreted as “people from the hill,” since pugo means hill. During the Spanish colonial period, mountain peoples were generally referred to as Igorot or Ygolote, but the inhabitants of Ifugao preferred the name Ifugao.

Ifugao Language belongs to the Northern Philippine branch of the Austronesian language family. The largest member of this branch is Ilocano. Ifugao's closest relatives are the neighboring Cordillera languages, Bontok and Kankanay, from which linguists estimate it began to diverge 1,000 years ago. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

RELATED ARTICLES:

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

Ifugao Population and Where They Live

According to the 2024 Philippines census there was a total of 208,668 people living in Ifugao province, with a density of 79 inhabitants per square kilometer (200 inhabitants per square mile) . About two thirds belong to the Ifugao ethnic group, which means there are about 140,000 Ifugao in Ifugao Province. Many also live outside the province. In 2000, Ifugao constituted 67.9 percent of the population of the Ifugao province, numbering almost 110,000. The next largest group were the Ilocanos, who made up 13.7 percent of the province. At that time over 23,000 Ifugao lived in Nueva Vizcaya province. There were an estimated 133.000 Ifugao in the late 2000s. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009, Wikipedia]

Ifugao Province is the traditional homeland of the Ifugao people and where many continue to live today. Ifugao Province includes the municipalities of Lagawe (the provincial capital), Aguinaldo, Alfonso Lista, Asipulo, Banaue, Hingyon, Hungduan, Kiangan, Lamut, Mayoyao, and Tinoc. One of the smallest provinces in the Philippines, Ifugao covers only about 2,518 square kilometers (square miles), roughly 0.8 percent of the country’s total land area. The province has a temperate climate and is rich in forest and mineral resources.

Ifugao Province is located in the rugged uplands in northern Luzon's Cordillera Central (which includes peaks that are over 2,440 meters (8,000 feet) high. The area is drained by tributaries of the Magat River, which in turn joins the upper course of the Cagayan River. The region is famous for the rice terraces carved into the steep mountainsides,

While most Ifugao continue to live within Ifugao Province, others have migrated to Baguio — often working as woodcarvers — or to other parts of the Cordillera. The Ifugao are divided into several subgroups based on variations in dialect, customs, and costume designs and colours. The principal subgroups are the Ayangan, Kalangaya, and Tuwali.

Ifugao Groups

The Ifugao people are primarily divided into three main ethnolinguistic subgroups based on dialect, tradition, and costume differences: 1) Tuwali (Central, Kiangan), 2) Ayangan (Eastern, Northern), and 3) Kalanguya (Southern). Other notable groups include the Batad and Mayoyao. The term "Igorot" covers the broader Cordillera region, of which the Ifugao are one of several distinct tribes. [Source: Google AI, Wikipedia]

Tuwali live in the southern part of Sub-dialects include Hapao, Lagawe, and Hungduan. Ayangan reside mainly in eastern and northern municipalities such as Banaue and Mayoyao. They make up about half of the total Ifugao population. Kalanguya are found mostly in southern areas such as Tinoc. They are sometimes categorized as a distinct, yet closely related, cultural group based on their unique traditions and significantly different dialect. Other distinct dialects identified include Batad, Amganad, and Mayoyao.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Batad Ifugao population was 15,000 and the Amganad Batad Ifugao population was 38,000 in the early 2020s. Estimates for the various Ifugao dialect-groups are as follows: Amganad: 27,000 (1987); Batad: 43,000 (1987); Mayoyao: 40,000 (1998); and Tuwali (Kiangan): 50,786 (1990). Population density is as high as 155 persons per square kilometers (400 per square mile) in some locales.

History of the Ifugao

Among the highland peoples of Southeast Asia, the Ifugao were notable for being known by their own name rather than by a generic label for mountain dwellers, which in the case of the northern Philippines is Igorot, a term first recorded by the Spanish for gold-trading mountaineers. Because these groups resisted Spanish rule, acculturation, and Christianization for centuries, they were labeled by the Spanish as infidels and fierce, independent tribes. This distinction separated them sharply from the lowland indios, who paid tribute and adopted Spanish customs. As a result, the Ifugao retained a strong reputation for autonomy and resistance. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

Scholars have proposed differing theories regarding the origins of the Ifugao. Henry Otley Beyer argued that they migrated from southern China around 2,000 years ago, eventually settling in the Cordillera valleys. Felix Keesing, drawing on Spanish sources, suggested a much later migration from the Magat area after Spanish arrival, implying that the rice terraces were only a few centuries old. This view was echoed in themes found in the Ifugao epic Hudhud. Manuel Dulawan later proposed that the Ifugao originated from the western Mountain Province, citing linguistic, architectural, and cultural similarities with the Kankanaey. These competing theories reflected broader debates over migration, adaptation, and continuity in Cordillera history.

Studies indicated that the Ifugao repeatedly resisted Spanish conquest, and that many highland groups consisted of populations fleeing colonial control in the lowlands. The rugged terrain alone did not explain Spanish failure, since other mountainous regions were successfully colonized. Archaeological research instead showed that the Ifugao strengthened their political and economic systems in response to external threats. Population growth and colonial pressure encouraged a shift toward wet-rice agriculture. This transformation marked a strategic adaptation rather than a passive survival. It laid the groundwork for the intensive terrace systems that later defined Ifugao society.

Research by Queeny Lapeña and Stephen Acabado emphasized that effective resistance required organized military and political structures. Spanish expansion into the Magat Valley pushed the Ifugao to resettle deeper into the Cordillera between 1600 and 1700. Soon after, they adopted wet-rice cultivation and constructed extensive rice terraces, replacing an earlier reliance on taro. Rice fields became ritual spaces that reinforced community solidarity and cultural identity. Growing populations, increased access to exotic goods, and greater use of ritual animals signaled rising political complexity. These developments were interpreted as deliberate responses to colonial pressure.

Within the Cordillera, the Ifugao belonged to the Central group alongside the Bontok, Kankanaey, and southern Kalinga, all famed for their terraced landscapes. Despite shared features, Ifugao society differed markedly from its neighbors. Unlike the Bontok village-ward system, Ifugao social life encouraged competition among wealthy and forceful individuals. This contentious ethos prevented the formation of region-wide peace-pact systems like those of the Kalinga. Nevertheless, Ifugao culture contributed iconic symbols to Philippine national identity. Their rice terraces and Hudhud chants later gained international recognition through UNESCO.

The Cordillera peoples were never completely isolated from the outside world. Spanish military expeditions and missionaries periodically entered the highlands, but made little lasting impact. More significant were Ilocano traders, whose regular exchanges with highlanders in the eighteenth century even undermined the colonial tobacco monopoly. The Ifugao’s main external conflict was with the Gaddang over control of the upper Magat Valley rather than with the Spanish directly. American colonial rule later integrated the Cordillera more fully into the Philippine state through troops, schools, and missions, while labeling its peoples as cultural minorities. The Japanese occupation brought further suffering and violence, ending with General Yamashita’s surrender at Kiangan in 1945. Subsequent administrative reforms eventually recognized Ifugao as a distinct province within a semi-autonomous Cordillera region.

Ifugao Headhunting

Most Ifugao headhunting has traditionally been the result of feuds between kin group and warfare with outsiders. Feuds often lasted a long time and traditionally only ended when there was a marriage between the feuding groups. Warfare usually took the form of raiding parties with a 100 or so men. The raiders not only took heads to display on skull shelves at their homes but also took slaves which they sold to lowlanders.

The Ifugao are said to have given up headhunting and feuding during the American occupation in the first part of the 20th century. However when I was there in 1989 I heard stories about a bus driver that hit and killed an Ifugao woman. The people in her village supposedly got a head hunting party together but were stopped before they could do anything.

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Mr. Worcester pointed out that whereas most of the men present were unarmed (at any rate, they had neither spears nor shields), in his early trips through this country, as elsewhere, every man came on fully armed, and the ground was stuck full of spears, each with its shield leaning on it, the owner near by with the rest of his ranchería, and all ready at a moment’s notice to kill and take heads. For although these people are all of the same blood and speak nearly the same language, still there is no tribal government; the people live in independent settlements (rancherías), all as recently as five or six years ago hostile to one another, and taking heads at every opportunity.

This state of affairs was undoubtedly partly due to the almost complete lack of communication then prevailing, thus limiting the activities of each ranchería to the growing of food, varied by an effort to take as many heads as possible from the ranchería across the valley, without undue loss of its own. And what is said here of the Ifugao is true also of the Ilongot, the Igorot, the Kalinga, the Apayao, and of all the rest of the head-hunting highlanders of Northern Luzon. The results accomplished by Mr. Worcester with all these people simply exceed belief. But this subject, being worthy of more than passing mention, will be considered later. The afternoon is wearing on, and we must get at the two exceptions mentioned some little time ago. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Burial of a Headless Corpse in Banaue

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The friends of a beheaded person take his body home from the scene of death. It remains one day sitting in the dwelling. Sometimes a head is bought back from the victors at the end of a day, the usual price paid being a carabao. After the body has remained one day in the dwelling it is said to be buried without ceremony near the trail leading to the village which took the head. The following day the entire ato has a ceremonial fishing in the river, called “mang-ogao” or “tid-wil.” A fish feast follows for the evening meal. The next day the mang-ayyu ceremony occurs. At that time the men of the ato, go near the place where their companion lost his head and ask the beheaded man’s spirit, the pinteng, to return to their village. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

One photograph taken in April, 1903 shows the burial of a beheaded corpse in Banaue. After the head-taking the body was set up two days under the dwelling of the dead man, and was then carried to the mountain side in the direction of Kambulo, the village which killed the man. It was tied on a war shield and the whole tied to a pole which was borne by two men. The funeral procession was made up as follows: First, four warriors proceeded, one after the other, along a narrow path on the dike walls, each beating a slow rhythm with a stick on the long, black, Banaue war shield, each shield, however, being striped differently with white-earth paint. The corpse was borne next, after which followed about a dozen more warriors, most of whom carried the white-marked shield—an emblem of mourning.

About half a mile from the dwelling the party left the fields and climbed up a short, steep ascent to a spot resembling the entrance to the earth burrow of some giant animal, and there the strange corpse was placed on the ground. A small group of people, including one old woman, was awaiting the funeral party. At the back end of the burrow two men tore away the earth and disclosed a small wall of loose stones. These they removed and revealed a vertical entrance in the earth about 2 feet high and 2½ feet wide. Through this small opening one of the men crawled, and crouching in the narrow sepulcher scraped up and threw out a few handfuls of earth. We were told that the corpse before us was the fifth to be placed in that old tomb, all being victims of the village of Kambulo, and four of whom were descendants of the first man buried at that place—certainly “blood vengeance” with a vengeance.

We were without means of understanding the two or three simple oral ceremonies said over the body, but the woman played a part which it is understood she does not in the Bontoc area. She carried a slender, polished stick, greatly resembling a baton or “swagger stick,” and with this stood over the gruesome body, thrusting the stick again and again toward and close to the severed neck, meanwhile repeating a short, low-voiced something. After the body was cut from its shield a blanket was wrapped about it—otherwise it was nude, save for a flayed-bark breechcloth—and it was set up in the cramped sepulcher facing Kambulo, and sitting supported away from the earth walls by four short wooden sticks placed upright about it. An old bamboo-headed spear was broken in the shaft and the two sections placed with the corpse.

The stones were again piled across the entrance, and when all was closed except the place for one small stone a man gave a few farewell thrusts through the opening with a stick, uttering at the same time a short low sentence or two. The final stone was placed and the earth heaped against the wall.

The pole to which the corpse was tied when borne to the burial was placed horizontally before the tomb, supported with both ends resting on the high side walls of the burrow, and on it were hung a dozen white-bark headbands which were worn, evidently, as a mark of mourning, by many of the men who attended the burial. How long it would be, in a state of nature, before the tomb would be required for another burial is a matter of chance, but a relative, frequently a son, nephew, or brother of the dead man, would be expected to avenge the dead man on the village of Kambulo, with chances in favor of success, but also with equal chances of ultimate loss of the warrior’s head and burial where six kinsmen had preceded him.

Ifugao Festivals

During ceremonies that pay homage to the anitos (spritits) clan leaders wear headdresses adorned with wild pig tusks, hornbill beaks and feathers and monkey skulls. The hornbill is considered to be the messenger of the gods and the monkey is a comic symbol. According to custom and tradition the monkey skull on a head dress must face in the same direction as the person wearing it. [Source: "Vanishing Tribes" by Alain Cheneviére, Doubleday & Co, Garden City, New York, 1987**]

During a festival to mark the planting of the crop in March or February the Ifugao hold a ceremony known as “ulpi” in which they leave the terraces for a few days and socialize, smoke and drink a palm liquor called “bayah”. During the harvest in July they thank the spirits by sacrificing chickens and then study the blood for omens. If everything is satisfactory the blood is smeared on wooden idols that watch over the grain supply. **

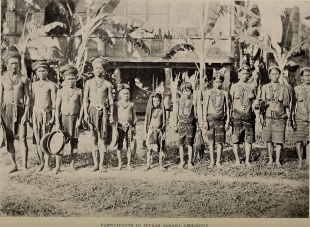

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “We moved up to the little parade in front of the cuartel, where an enormous crowd had already assembled. As at Campote, so here, and for the same reasons, very few old women were present, but about as many young ones and children as there were men. Our approach was the signal for the dancing to begin, and once begun, it lasted all day, the gansas never ceasing their invitation. Apparently anybody could join in, and many did, informal circles being formed here and there, for the Ifugaos, like all the other highlanders, dance around in a circle. Both men and women took part, eyes on a point of the ground a yard or so ahead, the knees a little bent, left foot in front, body slightly forward on the hips, left arm out in front, hand upstretched with fingers joined, right arm akimbo, with hand behind right hip. The musicians kneel, stick the forked-stick handle of the gansa in their gee-strings, with the gansa convex side up on their thighs, and use both hands, the right sounding the note with a downward stroke, the left serving to damp the sound. The step is a very dignified, slow shuffle, accompanied by slow turns and twists of the left hand, and a peculiar and rapid up-and-down motion of the right. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“True to what had been said the day before, a particularly large circle was formed, and Cootes and I were invited to join, which we did; if any conclusion may be drawn from the applause we got (for the Ifugaos clap hands), why, modesty apart, we upheld the honor of the Service. Every now and then the orators had their turn, for a resounding “Whoo-o-ee!” would silence the multitudes, and some speaker would mount the tribune and give vent to an impassioned discourse. One of these bore on the killing of the prisoner that morning: the orator declared that he was a bad man, and that he had met with a just end, that the people must understand that they must behave themselves properly, and so on. I forget how many speeches were made; but the tribune was never long unoccupied. Another performance of the day was the distribution of strips of white onion-skin paper. On one of his previous trips Mr. Worcester had noticed that the people had taken an old newspaper he had brought with him, cut it up into strips, and tied them to the hair by way of ornament.

“People kept on coming from their rancherías, one arrival creating something of a stir, being that of the Princesa, wife of the orator who had welcomed us the day before. She came in state, reclining in a sort of bag hanging from a bamboo borne on the shoulders of some of her followers. She had an umbrella, and, if I recollect aright, was smoking a cigar. On emerging from her bag, a circle formed about her, and she was graciously pleased to dance for us, no one venturing to join her. As she was fat and scant o’ breath,2 her performance, was characterized by portentous deliberation, precision, and dignity, and was as palpably agreeable to her as it was curious to us.”

Ifugao Folklore and Culture

The Ifugao possess a verse epic known as the Hudhud. Individual episodes are sung to ease the monotony of the rice harvest, with a female soloist leading and the other workers responding in chorus. The epic’s heroes are typically kadangyan—wealthy, high-status individuals—such as Bugan, a female kadangyan who fights as courageously as her brother Dinulawan and vows to marry only the man capable of fitting her brother’s sword belt. A poor man named Daulayan succeeds in doing so and is later revealed to be of kadangyan lineage himself. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

A central element of the Ifugao marriage ceremony is the myth of Bali-tok and Bugan of Kiangan, a brother and sister who survive a great flood and become the ancestors of the Ifugao. In one version of the story, Bugan, ashamed of becoming pregnant by her brother, travels downstream (lagod) seeking death at the hands of the spirits. Instead, they teach her how to lift the curse of incest by sacrificing a male and female pig from the same litter. In another version, Bugan, devastated by childlessness, goes downstream in search of death and encounters Fire, a crocodile, and a shark, each of whom she impresses with her courage and beauty. The shark delivers her to Umbumabakal, who lives in a terrifying house covered with enormous ferns. There Bugan offers herself to be devoured, but Umbumabakal takes pity on her and brings her to Ngilin and the gods of Animal Fertility. Together they return to Kiangan and instruct the priests in performing the bubun ceremony, in which sacrificial meat is divided between Ambahing, the spirit who steals semen from the womb, and Komiwa, the spirit who stirs semen within it. ~

Cordillera peoples play a wide variety of musical instruments, including nose flutes (kalleleng), lip flutes (paldong), whistle flutes (olimong), panpipes (diwas-diwas), buzzers (balingbing), tube zithers (kolitong), half-tube percussion instruments (palangug), stamping tubes (tongatong), and jaw harps (giwong). Reflecting the historical importance of Chinese trade connections over those with Southeast Asia, their gongs (gangsa) are flat rather than knobbed, with different tones produced by strokes, slaps, and sliding motions. ~

One significant male dance is the cockfight dance performed before battle. Other male dances involve men moving in circles while striking gongs. Female dances, by contrast, emphasize a rigid posture and the controlled raising of outstretched arms. ~

Ifugao Headhunter Dance

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “The great performance of the morning, however, was a head-hunter dance, arranged by Barton; that is, he had gone out a day or two before and told a neighboring ranchería, that they must furnish a show of the sort for the apos whose visit was imminent. But, according to the old women of the village, he had made a great mistake in that he said it was not necessary to hold a cañao in advance. A cañao (buni in Ifugao), as already explained, is a ceremonious occasion, celebrated by dancing, much drinking of bubud, the killing of a pig, speeches. Whenever an affair of moment is in hand, such as a funeral or a head-hunting expedition, a cañao is held. Our entire stay at Kiangan might be called a cañao, or, rather, it was made up of cañaos. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“Now when Barton, two or three days before, refused to cañao, the old women shook their heads, declaring that something would happen, and the killings of the morning were at once summoned as proof that they were right and he was wrong. However this may be, not long after the Princesa’s dance we heard below us a cadenced sound and saw a long column in file slowly approaching. Its head was formed of warriors armed with spears and shields stained black with white zig-zags across; the leading warrior walked backward, continually making thrusts at the next man with his spear. A pig had immediately preceded, trussed by his feet to a bamboo, and interfering mightily with the music that followed. This was percussive in character, and was produced by twenty-five or thirty men beating curved instruments, made of very hard, resonant wood, with sticks. These musicians marched along almost doubled over, and would lean in unison first to the right and then to the left, striking first one end, then the other of their instruments, which they held in the middle by a bejuco string from a hole made for the purpose. The note was not unmusical. Many of the men had their head-baskets on their backs, and one or two of them the palm-leaf rain-coat. I had never imagined that it was possible for human beings to advance as slowly as did these warriors; in respect of speed, our most dignified funerals would suffer by comparison.

“The truth is, they were dancing. They got up the hill at last, however; laid the pig down in the middle of the vast circle that had instantly formed, and then began the ceremonious head-dance. Two or three men, after various words had been said, would march around in stately fashion, winding up at the pig, across whose body they would lay their spears. On this an old man would run out, and remove the spears, when the thing would be repeated. At last, a tall, handsome young man, splendidly turned out in all his native embellishments, on reaching the pig, allowed his companions to retire while he himself stood, and, facing his party with a smile, said a few words. Then, without looking at his victim, and without ceasing to speak, he suddenly thrust his spear into the pig’s heart, withdrawing it so quickly that the blade remained unstained with blood; as quick and accurate a thing as ever seen! Of course, this entire cañao was full of meaning to the initiated. Barton said it was a failure, and he ought to know; but it was very interesting to us. I was particularly struck by the bearing of these men, their bold, free carriage and fearless expression of countenance.”

Hudhud Chants of the Ifugao

The Hudhud chants of the Ifugao were inscribed in 2008 by UNESCO on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The Hudhud consists of narrative chants traditionally performed by the Ifugao community, which is well known for its rice terraces extending over the highlands of the northern island of the Philippine archipelago. It is practised during the rice sowing season, at harvest time and at funeral wakes and rituals. Thought to have originated before the seventh century, the Hudhud comprises more than 200 chants, each divided into 40 episodes. A complete recitation may last several days. [Source: UNESCO]

Since the Ifugao’s culture is matrilineal, the wife generally takes the main part in the chants, and her brother occupies a higher position than her husband. The language of the stories abounds in figurative expressions and repetitions and employs metonymy, metaphor and onomatopoeia, rendering transcription very difficult. Thus, there are very few written expressions of this tradition. The chant tells about ancestral heroes, customary law, religious beliefs and traditional practices, and reflects the importance of rice cultivation. The narrators, mainly elderly women, hold a key position in the community, both as historians and preachers. The Hudhud epic is chanted alternately by the first narrator and a choir, employing a single melody for all the verses.

The conversion of the Ifugao to Catholicism has weakened their traditional culture. Furthermore, the Hudhud is linked to the manual harvesting of rice, which is now mechanized. Although the rice terraces are listed as a World Heritage Site, the number of growers has been in constant decline. The few remaining narrators, who are already very old, need to be supported in their efforts to transmit their knowledge and to raise awareness among young people.

Ifugao Crafts

The Ifugao are skilled in metallurgy, employing the lost-wax process, as well as in basketry, weaving, and ikat (tie-dyeing). Their woodcarving tradition is especially renowned for bulol, cowrie-shell-eyed figures of male and female deities shown in fighting stances, armed and ready, or squatting with bowls extended in their hands. Other notable carvings include canes with elaborately carved handles, polished dining bowls with side compartments for condiments, chests with handles shaped like pigs’ heads, and shelves incorporating crocodile snouts and tails into their designs. In contemporary times, artisans also produce items tailored to tourist tastes—Western, generic Filipino, Chinese, and Japanese—such as ashtrays and mobile phone holders. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “ “At Banawe we saw more examples of native arts and crafts than we had heretofore. For example, the pipe is smoked, and we saw some curious specimens in brass, much decorated with pendent chains; others were of wood, some double-bowled on the same stem. Some of the men wore helmets, or skull-caps, cut out of a single piece of wood. Other carved objects were statuettes, sitting and standing; these are anitos, frequently buried in the [122] rice-paddies to make the crop good; besides, there were wooden spoons with human figures for handles, the bowls being symmetrical and well finished. Then there were rice-bowls, double and single, some of them stained black and varnished. Excellent baskets were seen, so solidly and strongly made of bejuco as to be well-nigh indestructible under ordinary conditions. Mr. Maimban got me a pair of defensive spears (so-called because never thrown, but used at close quarters) with hollow-ground blades of tempered steel, the head of the shaft being wrapped with bejuco, ornamentally stained and put on in geometrical patterns.” [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Since the end of World War II the production and sale of woodcarvings has become and important source of income for the Ifugao. They also have skills in making bowls, baskets, weapons and clothing. The mountain tribes of Luzon traditionally distinguished themselves by their cultural expressions, clothing and adornment. The Ifugao still practice the same skills as in the past: Woodcarving and weaving clothes. They discovered the tourists are a welcome clienta for their products as most young Ifugao prefer Western clothes. [Source:philippines.hvu.nl]

Bulul — Ifugao Male Rice Deity Figures

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a bulul, an Ifugao male rice deity figure. Dating to the 19th-20th century, it is made of wood, fiber and shell and is 66 × 19.1 × 17.8 centimeters (26 inches high, 7.5 inches wide and inches deep). Eric Kjellgren wrote: The most desirable and ceremonially important food in lfugao culture is rice, In lfugao religion the growth and abundance of rice is controlled by bulul, a group of deities who have the power not only to ensure a bountiful harvest but also to magically increase the quantity of the crop even after it is stored in the family granaries.To ensure that the bulul continue to bestow their fertile powers, families commission and consecrate wood images, also known as bulul, in which the rice deities reside during ceremonies and where a vestige of their power lingers, allowing them to easily reenter the figures as necessary.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Depicted as either seated or standing human figures, bulul are typically carved in male-female pairs. The sexual characteristics of the figures, however, are often subtly marked , so that their gender can be difficult to determine. The figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection sits atop two projections, which raise it slightly off the base to allow it to be dressed in a loincloth, indicating that it represents a male bulul. The distinctive hourglass-shaped bases of both male and female bulul likely represent stylized rice mortars, which further emphasize the link between bulul and rice.

Bulul from the Hapao region of Luzon are typically single male figures carved with their hands resting on slightly bent knees situated on a rectangular, mortar-shaped base with a deep groove in the center. According to Metropolitan Museum of Art: There is a strength and firmness to the pose that speaks to the ancestral power of this vessel. Across Luzon there is a diversity of carving styles used to create bulul. Other examples can be seen standing with their arms held straight at their sides, or seated, with arms resting on bent knees. Early examples are always bald, though some more recent bulul do have human hair attached to their heads. Others are carved with a ridge around their heads to suggest the presence of hair. The holes drilled in the bulul’s ear lobes are so rice stalks could be inserted.

Rituals and Ceremonies Involved in Making Bulul

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Ceremonies and festivities are associated with every stage of the creation of a bulul, from the selection of the tree, harvesting the wood, carving the figure and the performance of rituals to ensure that the bulul ancestor spirit will enter the vessel. Bulul are traditionally carved from the wood the narra tree associated in Ifugao cosmology with health, happiness and prosperity. Once the carving is complete, it is consecrated through a ritual that involves the recitation of the myth of Humidhid, the deity who made the first bulul. The figure is then bathed in the blood of sacrificial pigs. Following the ritual, the bulul will remain in the home of the commissioner for a period, after which time it will be placed in the granary to protect the rice crop from malevolent spirits. During harvest ceremonies the figures are brought back into the house, where they are presented with offerings of rice wine, cakes and the blood of sacrificial animals.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Requiring specific rituals for each phase of their creation, the carving of bulul is a costly and time-consuming process, often requiring six or more weeks to complete, and as a result only prosperous families can typically afford to commission the figures. Once the commission has been received, the deities must approve the individual tree selected. For carving bulul, artists typically choose the narra, a tree that is associated with health, happiness, and prosperity in lfugao cosmology. The initial carving takes place in the forest, after which the unfinished images are brought to the owner's house, where an entrance ceremony is performed. Sometime afterward, another ceremony is held to initiate the final stages of the carving, which proceeds only during daylight hours, followed by nights of dancing and feasting. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

A number of carvers may work on the images, but the final details are completed by the one who is recognized as the most accomplished artist. When the figures are complete they are ritually consecrated through the recitation of an oral tradition, which describes the supernatural origin of the first bulul images, and are anointed with the blood of sacrificial pigs. Once consecrated, the bulul are placed in the family granary and serve as guardians, protecting the rice crop from natural and supernatural enemies. During harvest ceremonies, they are brought back to the house and, along with ancestors and other deities, invited to join in the celebrations. Honored with offerings such as rice wine, rice cakes, and the blood of sacrificial animals, the bulul are asked again to help the harvested rice to magically increase. Through years of ritual use, many bulul images develop a deep black crusty patina, such as that seen on the present work.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026