HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON

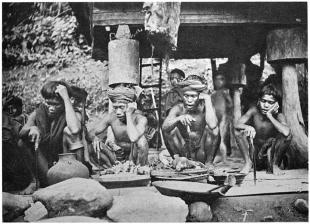

Several of the ethnic groups in northern Luzon were headhunters. They took heads in feuds with enemies. Men have traditionally worn loincloths and women have worn sarongs and a jacket or blouse. The loincloths worn by Luzon highlanders usually have horizontal stripes. In the old days they made tools and jewelry from copper, iron and gold they mined themselves.

Among the headhunting tribes are the Ifugao, Bontoc, Ilongot, Sagada Igorot, Kalingas, and Apayaos. These ethnic group live chiefly in the Cordillera Central of northern Luzon. These groups have traditionally been somewhat hostile towards each other and didn’t trade much out of fear of being attacked.

The custom of headhunting was largely suppressed by the constabulary before World War II. Under the Spanish these ethnic groups were left largely untouched. American missionaries, and workers with mining and timber companies, had more of an impact on them. The Marcos government say them mainly as obstacles that got in the way of development and making money.

The former headhunters of northern Luzon are now often the head hunted. In a 1986 National Geographic story two women members of the Itneg tribe and a former priest which had become members of the NPA were ambushed and beheaded by members of the Philippine army. Their heads were paraded through nearby villages on sticks then buried some distance from the bodies.

RELATED ARTICLES:

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

BUGKALOT (ILONGOT): LIFE, CULTURE, CUSTOMS, SOCIETY, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

ILONGOT IN THE 1910s factsanddetails.com

KALINGA: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

KALINGA IN 1910 factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

Reasons for Head Hunting

Heads taken in headhunting raids brought glory to the warrior who collected them and good luck to their village. They were usually preserved and worshiped in special rituals. Among some culture, certain parts of the body—the heart, brains, blood and liver—were believed to bring power to those who consumed them. Cutting out the heart, it was believed, destroys the evil that is believed to reside in that organ. Some tribal people also believe that head hunting helps soil fertility and give a person strength. Heads are sometimes used as a dowry, to strengthen buildings, protect against attacks, and display status.

Most heads are taken out as an act of revenge, often for the breaking of “adat” ("traditional law"). Richard Lloyd write in the Independent, "Decapitation and cannibalism are the deeply symbolic practices, the ultimate humiliation of a defeated enemy. Cut someone's head off and you reduce him to a pantomime mask. This is the point about severed heads—they don't look fearful so much as comical, like Halloween pumpkins.”

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: Some dozen causes for head-hunting among Malayan groups have been here cited. These include the debt of life, requirements for marriage, desire for abundant fruitage and harvest of cultivated products, the desire to be considered brave and manly, desire for exaltation in the minds of descendants, to increase wealth, to secure abundance of wild game and fish, to secure general health and activity of the people, general favor at the hands of the women, fecundity of women, and slaves in the future life. “Debt of life” means that if a group of people loses a head it is their duty within a code of honor to cancel the score by securing a head from the the group that took their head. In this way the score is never ended or canceled, since one or the other group is always in debt. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

It seems not improbable that the heads may have been cut off first as the best way of making sure that a fallen enemy was certainly slain. The head was at all events the best proof to a man’s tribesmen of the discharge of the debt of life; it was the trophy of success in defeating the foe. Whatever the cause of taking the head may have been with the first people, it would surely spread to others of a similar culture who warred with a head-taking tribe, as they would wish to appear as cruel, fierce, and courageous as the enemy.

The Ibilao of Luzon, near Dupax, of the Province of Nueva Vizcaya, give the name “debt of life” to their head-hunting practice; but they have, in addition, other reasons for head taking. No man may marry who has not first taken a head; and every year after they harvest their unhusked rice the men go away for heads, often going journeys requiring a month of time in order to strike a particular group of enemies. The Christians of Dupax claim that in 1899 the Ibilao took the heads of three Dupax women who were working in the rice fields close to the village. These same Christians also claim that they have seen a human head above the stacks of harvested Ibilao unhusked rice; and they claim the custom is practiced annually, though the Ibilao deny it.

Religious Connections to Headhunting?

Within the complex polytheist and animist beliefs of some groups, beheading one’s enemy was seen as the way of killing off for good the spirit of the person who had been killed. The spiritual significance of the ceremony also lay in the belief that at the end of mourning for the community's dead. The heads were put on display at traditional burial rites, where the bones of relatives were dug out from the earth and cleaned before being put in burial vaults. Ideas of manhood were also bound up with the practice, and the taken heads were surely a reward.”

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote:The people of Bontoc, say that their god, Lumawig, taught them to go to war. When, a very long time ago, he lived in Bontoc, he asked them to accompany him on a war expedition to Lagod, the north country. They said they did not wish to go, but finally yielded to his urgings and followed him. On the return trip the men missed one of their companions, Gu-manûb. Lumawig told them that Gu-manûb had been killed by the people of the north. And thus their wars began—Gu-manûb must be avenged. They have also a legend in regard to head taking: The Moon, a woman called “Kabigat,” was sitting one day making a copper pot, and one of the children of the man Chalchal, the Sun, came to watch her. She struck him with her molding paddle, cutting off his head. The Sun immediately appeared and placed the boy’s head back on his shoulders. Then the Sun said to the Moon: “Because you cut off my son’s head, the people of the Earth are cutting off each other’s heads, and will do so hereafter.” [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

But the possession of a head is in no way a requisite to marriage. A head has no part in the ceremonies for unhusked rice fruitage and harvest, or in any of the numerous agricultural or health ceremonies of the year. It in no way affects a man’s wealth, and, so far as I have been able to learn, it in no way affects in their minds a man’s future existence. A beheaded man, far from being a slave, has special honor in the future state, but there seems to be none for the head taker. As shown by the Lumawig legend the debt of life is the primary cause of warfare in the minds of the people of Bontoc, and it is today a persistent cause. Moreover, since intervillage warfare exists and head taking is its form, head-hunting is a necessity with an individual group of people in a state of nature. Without it a people could have no peace, and would be annihilated by some group which believed it a coward and an easy prey.

Bugkalot Headhunting

The Bugkalot are a forest people that live in the southern Sierra Madre and Caraballo mountains on the eastern side of Luzon in the Philippines. Also known as Ilongot, Ibilao, Ibilaw, Ilungut, Ilyongt and Lingotes, they reside primarily in the provinces of Nueva Vizcaya and Nueva Ecija, as well as along the mountain border between the provinces of Quirino and Aurora. They are former headhunters and live in an enclave and have resisted attempts to assimilate them. Renato Rosaldo studied headhunting among the Bugkalots in his book “Ilongot Headhunting, 1883-1974: A Study in Society and History”. He said that headhunting raids were often associated with bereavement and rage over the loss of a loved one. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the old days, every male Bugkalot was expected to engage in headhunting, ideally before marriage, and most men in the recent past had done so. Unlike some other headhunting societies, the Bugkalot did not take heads to magically enhance soil fertility, to accumulate personal spiritual power, to gain social prestige, or solely to pursue vendettas. Instead, a man took a head in order to “relieve his heart” of anxiety, which might stem from a death within his household or from an unresolved feud. Often he made a binatan, an oath of personal sacrifice—for example, abstaining from rice from the granary or refraining from sexual relations until he had taken a head. Successfully taking a head entitled a young man to wear prestigious ornaments such as cowrie shells, feathers, and red hornbill decorations. While the act did elevate his standing, because all men underwent the same experience it ultimately reinforced the society’s overall egalitarianism. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Men hunted heads either alone or in raiding parties that could number up to forty individuals. Before departure, they gathered in front of a house, where a shaman summoned the souls of the intended victims into a bamboo container. In the forest, the men listened for bird omens and sometimes played instruments associated with death, such as a violin or reed flute. Distinctions were sought in being the first to strike or shoot, to reach a fallen body, to sever a head, or to fling it away. The heads themselves were not kept, unlike in cultures where skulls were preserved as symbols of status or sources of spiritual power, though hands might be brought back for children to chop apart. The return of the headhunters was marked by communal celebration, including singing, dancing, and the slaughter of a pig. ++

Peace between hostile groups was established through a series of debates and exchanges, after which members of the opposing sides might visit one another, intermarry, or even conduct joint raids against other groups. If no intermarriage occurred, however, hostilities typically resumed within two generations. ++

Apayao Headhunters in the 1900s

The Isneg, an Igorot group, used to be called the Apayao. In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “So far as is known, no white man had ever penetrated the southern and central portions of Apayao until” Mr. Worcester, suitably accompanied and escorted, crossed the Cordillera, in 1906, from North Ilokos. A later expedition, commanded by a Constabulary officer, was attacked, not necessarily from any hostility to it as such, but because it was accompanied by natives hostile to a ranchería (Guenned) approached on the way. A punitive expedition, led by the same officer, afterward met with some success, but American popularity suffered in consequence. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

The Apayao country is the only sub-province under a native Governor, and its Governor, Señor Blas Villamor, is the only Filipino that has ever shown any interest in or sympathy for the highlanders. His task has been a difficult one; for example, his only line of communication, the Abulug River, runs through a territory inhabited by Negritos, who had been so abused by the Christian natives on the one hand, and whose heads had been so diligently sought by the wild Tinguians of the mountains, on the other, that they had acquired the habit of greeting strangers with poisoned arrows. His mountain region itself was inhabited by inveterate head-hunters, most of whom had never even seen a white man. Conditions are improving, however; the raids against the Christian and Negrito inhabitants of the lowlands of Cagayán have been completely checked, and Mr. Worcester hopes that head-hunting will diminish. It still exists.

Strong told me, on his return to Manila, that, looking into a head-basket after leaving Tabuk, he found in it fresh fragments of a human skull; for the Apayaos take the skull like the other highlanders, but unlike them, break it into pieces. But with these people head-hunting is a part of their religious belief, and so all the harder to uproot. With the others it is a matter of vengeance, or else even of sport. “On the other hand, the people of Apayao have many good qualities. They are physically well-developed and are quite cleanly. They erect beautifully constructed houses. Their women are well clothed, and both men and women love handsome ornaments. They are quite industrious agriculturists and are now begging for seed and for domestic animals in order that they may emulate their Christian neighbors in the raising of agricultural products.”

Ifugao Headhunting

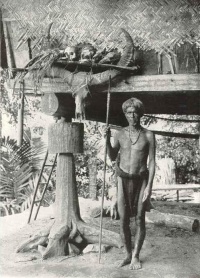

Most Ifugao headhunting has traditionally been the result of feuds between kin group and warfare with outsiders. Feuds often lasted a long time and traditionally only ended when there was a marriage between the feuding groups. Warfare usually took the form of raiding parties with a 100 or so men. The raiders not only took heads to display on skull shelves at their homes but also took slaves which they sold to lowlanders.

The Ifugao are said to have given up headhunting and feuding during the American occupation in the first part of the 20th century. However when I was there in 1989 I heard stories about a bus driver that hit and killed an Ifugao woman. The people in her village supposedly got a head hunting party together but were stopped before they could do anything.

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Mr. Worcester pointed out that whereas most of the men present were unarmed (at any rate, they had neither spears nor shields), in his early trips through this country, as elsewhere, every man came on fully armed, and the ground was stuck full of spears, each with its shield leaning on it, the owner near by with the rest of his ranchería, and all ready at a moment’s notice to kill and take heads.

See Separate Article: IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Bontoc Headhunting

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in 1912: The practice of head-hunting still exists in the Bontok country, though the steady discouragement of the Government is beginning to tell. Here in Bontok itself, a boy, employed as a servant in the Constabulary mess, dared not leave the mess quarters at night; in fact, was forbidden to. For his father, having a grudge against a man in Samoki across the river, had sent a party over to kill him. By some mistake, the wrong man was killed, and it was perfectly well understood in Bontok that the family of the victim were going to take the son’s head in revenge, and were only waiting to catch him out before doing it. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

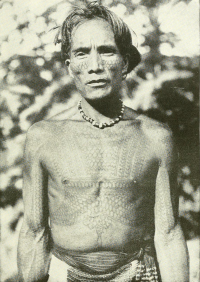

For unknown generations these people have been fierce head-hunters. Nine-tenths of the men in the villages of Bontoc and Samoki wear on the breast the indelible tattoo emblem which proclaims them takers of human heads. The fawi of each ato in Bontoc has its basket containing skulls of human heads taken by members of the ato. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

“These homicides can, however, be atoned without further bloodshed, if the parties interested will agree to it. A more or less amusing instance in kind was recently furnished by the village of Basao, which had in the most unprovoked manner killed a citizen of a neighboring ranchería.

See Separate Article: BONTOC HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026