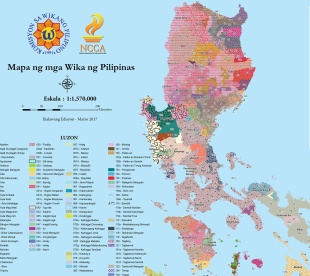

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CORDILLERA OF LUZON

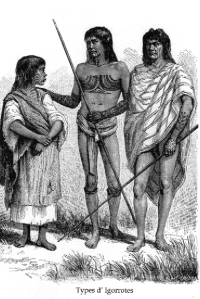

There are ten principal cultural groups living in the Cordillera of Central and Northern. The name Igorot, the Tagalog word for mountaineer, was often used with reference to all groups. At one time it was employed by lowland Filipinos in a pejorative sense, but in recent years it came to be used with pride by youths in the mountains as a positive expression of their separate ethnic identity vis-à-vis lowlanders. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Of the ten groups, the Ifugaos of Ifugao Province, the Bontocs of Mountain and Kalinga-Apayao provinces, and the Kankanays and Ibalois of Benguet Province were all wet-rice farmers who worked the elaborate rice terraces they had constructed over the centuries. The Kankanays and Ibalois were the most influenced by Spanish and American colonialism and lowland Filipino culture because of the extensive gold mines in Benguet, the proximity of Baguio, good roads and schools, and a consumer industry in search of folk art. Tribal groups on Luzon were widely known for their carved wooden figures, baskets, and weaving

Other mountain peoples of Luzon were the Kalingas of KalingaApayao Province and the Tinguians of Abra Province, who employed both wet-rice and dry-rice growing techniques. The Isnegs of northern Kalinga-Apayao Province, the Gaddangs of the border between Kalinga-Apayao and Isabela provinces, and the Ilongots of Nueva Vizcaya Province all practiced shifting cultivation. Negritos completed the picture for Luzon. Although Negritos formerly dominated the highlands, by the early 1980s they were reduced to small groups living in widely scattered locations, primarily along the eastern ranges of the mountains. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

BUGKALOT (ILONGOT): LIFE, CULTURE, CUSTOMS, SOCIETY, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

ILONGOT IN THE 1910s factsanddetails.com

KALINGA: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

KALINGA IN 1910 factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

Isneg (Apayao)

The Isneg people live in the the Cordillera Administrative Region of northern Luzon. Also known as the Apayao, Isnag, Isned, Kalina', Mandaya, and Payao, they live in small villages with an average of 85 people and practice slash and burn agriculture. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Dibagat-Kabugao Isneg population in the early 2020s was 49,000. Most practiced traditional animist religions and 10 to 50 percent were Christians, with 5 to 10 percent of these being Protestant Evangelicals. The Isneg bury the dead under the kitchen area of their homes. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

The Isneg inhabit the northwestern edge of northern Luzon, primarily in the upper half of Apayao Province in the Cordillera. The name Isneg comes from itneg, meaning “inhabitants of the Tineg River,” while Apayao is believed to derive from the battle cry Ma-ap-ay-ao, shouted with the hand rapidly clapped over the mouth. The people may also identify themselves as Imandaya if they live upstream, or Imallod if they live downstream. Their core municipalities include Pudtol, Kabugao, Calanasan, Flora, Conner, Sta. Marcela, and Luna. Isnag communities are also found in eastern Ilocos Norte—particularly Adams, Carasi, Marcos, Dingras, Vintar, Dumalneg, and Solsona—and in northwestern Cagayan, including Santa Praxedes, Claveria, Pamplona, and Sanchez Mira. Two major river systems, the Abulog and Apayao rivers, flow through Isneg territory. [Source: Wikipedia]

Isneg Burial Practices: The Isneg people wrap the deceased in a mat and carry it on their shoulders. Items are placed in the coffin to help the deceased on his or her journey. For instance, a jar (basi) is placed in the coffin to quench the deceased's thirst. Another example is placing a spear and shield inside to help protect the deceased from enemies during the journey. The coffin is then lowered into the kitchen area of the family home or a burial site owned by the family.

Itneg is a general term that refers to speakers of the Itneg languages. Also known as Itineg or Tinguian, they mainly speak Ilocano today and live northwestern Luzon living mainly in Abra, Ilocos Sur, and parts of Ilocos Norte. Believed to have descended from migrants from Kalinga, Apayao, and the Northern Kankana-ey, they identify themselves as Itneg, though Spanish colonizers referred to them as Tingguian. As of 2020, their population numbered about 100,800 and is divided into eleven subgroups. Itneg society values traditional handicrafts and measures social status by wealth, material possessions, and the ability to sponsor rituals and feasts. While distinctions between rich and poor exist, social classes are flexible, with opportunities for mobility through personal effort, and a middle group becoming distinct mainly during ceremonial events.

Isneg Life and Family

Isneg subsistence practices include upland rice cultivation, swidden farming, and fishing. They brew basi, a fermented sugarcane wine, stored in jars that are half-buried inside a small four-post shed called an abulor, located in the open space (linong or sidong) beneath their houses (balay). Bamboo plays an important role in Isnag cooking, serving as both cookware and food container. Traditional dishes include sinursur, made from catfish or eel cooked in bamboo with chili; abraw, a dish of freshwater crabs with coconut and chili; and sinapan, which resembles smoked meat. The Isnags make use of whatever nature provides, catching fish and other aquatic life from rivers, brooks, lakes, and streams, and gathering edible leaves from the forest. Chili remains a defining element of their cuisine and is used generously in cooking. [Source: Wikipedia]

Traditionally, the Isnags have eaten two meals a day—either in mid-morning and late afternoon, or at noon and in the evening. Rice is the staple food, but because harvests are often limited by labor shortages, rice is frequently scarce, prompting reliance on trade. Meals include vegetables and root crops such as camote, and occasionally fish, wild pig, or deer. Dogs, pigs, and chickens are eaten only during feasts, while eggs are rarely consumed because they are usually allowed to hatch. Before or after meals, families often gather around the hearth to drink home-grown coffee, while rice wine is reserved for festive occasions.

Traditional Isnag houses, known as balay, are two-story, single-room structures raised on four corner posts, with entry provided by a ladder. Beneath the house is an open space called the linong or sidong, which often contains a small shed (abulor) used to store jars of basi (rice wine). Nearby stands a bamboo pigpen (dohom). Rice granaries (alang) are also elevated on four posts and fitted with circular or flat rat guards. Temporary structures associated with upland and swidden farming are called sixay. Essential tools include the bolo (badang) and the axe (aliwa), and the Isnags are skilled fishermen.

Kinship groups and family clans form the core of Isnag social organization and are traditionally headed by the husband. Polygamy is allowed, provided the husband can support multiple families. Numerous taboos govern daily life and vary by locality. Pregnant women, for example, are discouraged from eating certain foods—such as specific types of sugarcane, bananas, and the soft meat of sprouting coconuts—to ensure the birth of a healthy child. In the past, twins are believed to be unlucky; when twins are born, the weaker child is sometimes allowed to die. If a woman dies in childbirth, the infant is also abandoned and usually buried with the mother. The Isnags do not observe formal rites of passage for adolescence, but they perform rituals connected to marriage, such as amoman (similar to the modern pamamanhikan), and death, including mamanwa, which is conducted by widowers.

Isnag kinship is bilateral, meaning children are equally related to both parents. Households consist of closely related families living near one another, and extended families of up to three generations may share a single balay. The family is the fundamental social unit, with larger families considered stronger and headed by the husband. Beyond the family, there is little formal social hierarchy, though brave men known as mengals traditionally lead in hunting and fishing. The bravest among them, the Kamenglan, serves as the overall leader. A man enters the ranks of the mengals after his first headhunting expedition. A mengal wears a red kerchief and bears tattoos on the arms and shoulders.

In regard to Apayao courtship and marriage customs, physical attractiveness for women was less important than physical strength and capacity for agricultural labor, particularly in kaingin (swidden) farming. As a result, women perceived as strong and industrious are favored over those regarded as physically delicate. Polygamy is traditionally permitted, mainly as a practical means of securing additional labor for large agricultural holdings, but it is relatively uncommon and generally motivated by economic necessity rather than personal desire.[Source: kasal.com]

Isneg Culture

Isneg woman in traditional dress typically wears a sinulpo (upper garment) and aken (wraparound cloth). Say-am is a major ceremonial feast held after a successful headhunting expedition or other significant events. Sponsored by wealthy families, it can last from one to five days or longer and is marked by dancing, singing, feasting, and drinking, with participants wearing their finest attire. A shaman, the Anituwan, offers prayers to the spirit Gatan before the first dog is sacrificed, if a human head has not been taken, and the offering is made at the sacred tree known as the ammadingan. On the final day of the celebration, a coconut is split in honour of Anglabbang, the guardian of headhunters. A similar but more modest ceremony, called Pildap, is hosted by poorer families. Conversion to Christianity increased after 1920, and today the Isnag are religiously divided, with some continuing to practise animist beliefs alongside Christianity.

Traditional dress is central to Isnag identity and is worn with pride at cultural and social gatherings. Isnag men traditionally wear a blue G-string called abag, paired with an upper garment known as bado on special occasions. For important events, they also wear the sipattal, an ornament made of shells and beads. In the past, warriors (mengal) wore red kerchiefs and bore arm and shoulder tattoos to mark bravery and achievements in head-taking expeditions. Isnag women are noted for their colorful attire. They wear a wraparound cloth called aken, with smaller versions for daily wear and larger ones for ceremonies. Their clothing is often adorned with elaborate ornaments and jewelry, reflecting a preference for bright, decorative dress during festivals and major rituals. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains an ornament (sipattal) made by the Isneg in the 19th-early 20th century from shell, beads, metal and fiber. It 87.6 centimeters (34.5 inches) Eric Kjellgren wrote: Living in the remote, mountainous interior of northern Luzon, the lsneg, like other highland peoples, maintain regular contact with the broader world through longestablished trading relationships with coastal groups. Among the lsneg the prestige and authority of individuals and families are intimately linked to wealth and, formerly, to men's achievements in warfare and head-hunting. lsneg wealth is comprised of trade goods, such as large ceramic jars, beads, and porcelain plates, laboriously transported to the distant mountain villages and passed down as heirlooms within families or, occasionally, exchanged between families during marriage ceremonies. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The human body is the primary focus of lsneg artistic expression and, on important occasions, both sexes adorn themselves with a diversity of colorful textiles and jewelry. The most visually striking of all lsneg jewelry is the sipattal, an elaborate ornament fashioned locally from mother-of-pearl and trade beads, precious materials obtained through exchange with coastal groups. Worn by men, women, and children, sipattal consist of clusters of bissin, bilobed mother-of-pearl ornaments, suspended from a chokerlike collar of multicolored trade beads. Sipattal can be worn with the bissin either displayed across the chest or, more rarely, draped down the back.

Ibaloi

The Ibaloi live in the Cordillera of northern Luzon and parts of eastern La Union in the Ilocos Region, Benguet and Nueva Vizcaya in the Cagayan Valley. Also known as the Benguetano, Benguet Igorot, Ibaluy, Inavidoy, Ivadoy, Ibaloy, Igador, Inibaloi, Inibaloy, Inibilio, and Nabaloi, they are wet rice farmers who have a tradition of ancestor worship and live in houses with pyramid-shaped thatch roofs. Contact with neighboring groups and the influence of Christianity has caused a great deal of local variation in Ibaloi culture. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)~]

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Inibaloi, Nabaloi population in the early 2020s was 213,000. In 1975 the Ibaloi numbered nearly 89,000. Most practice traditional animist religions and 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with 5 to 10 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. The Ibaloi recognize two categories of spirits (anitos): nature spirits associated with calamities, and ancestral spirits (ka-apuan), who communicate through dreams or illness within the family. The Ibaloi speak an Austronesian language that is closely related to Pangasinan, the language predominantly spoken in the neighbouring province of Pangasinan to the southwest of Benguet. The Ibaloi are associated most with Southern Benguet, the home to Baguio, the largest city in the Cordillera. The area is rich in mineral resources like copper, gold, pyrite, and limestone. [Source: Joshua Project]

Traditional Ibaloi houses (balai or baeng)I are scattered in agricultural fields or on hillsides. They contain a single room and are raised about two meters off the ground on posts and covered with pyramidal thatched roofs and have no windows. Wealthier families favor pine wood for construction, while poorer households use bark bamboo for walls and floors and cogon grass (atup) for roofing. Their diet is based on wet rice, tubers, beans, and maize, and is occasionally supplemented with the meat of pigs, dogs, chickens, water buffalo, horses, and cattle.Cooking is done using copper pots (kambung), wooden containers (shuyu), and simple hearths consisting of soil-filled wooden boxes (shapolan) and three-stone stoves (shakilan).

Traditional weapons include spears, shields, bows and arrows, and war clubs, though these are now rarely used. Rice cultivation relies on mortars (dohsung), pestles (al-o or bayu), and bamboo or rattan winnowers (dega-o or kiyag). Two main rice varieties are cultivated: kintoman, a red rice used both as food and for making rice wine (tafey), and talon, a white lowland rice planted during the rainy season. Other crops include camote, gabi, cassava, potatoes, cabbage, celery, and pechay, along with fruits such as avocado, banana, and mango. Diets also include wild game, fish from local rivers, and smoked pork known as kinuday.

Descent is bilateral on both male and female lines. There is a clear distinction between the wealthy and the poor, with considerable power and influence concentrated in the hands of the former. Ibaloi society is traditionally stratified into the wealthy elite (baknang) and several lower-status groups, including cowhands (pastol), farmhands (silbi), and non-Ibaloi slaves (bagaen). Social rank is closely associated with wealth, land ownership, and the ability to sponsor rituals and feasts.

Ibaloi Culture

Music plays an important ritual role in Ibaloi culture. Instruments such as the Jew’s harp (kodeng), nose flute (kulesheng), native guitar (kalsheng or kambitong), bamboo percussion instruments, drums (solibao), and gongs (kalsa) are considered sacred and are performed only for specific occasions, particularly during cañao feasts. Among the best-known Ibaloi dances is the bendian, a large-scale communal dance performed by hundreds of men and women. Originally a victory dance during times of war, it later evolved into a celebratory performance and is now featured as entertainment (ad-adivay) during cañao feasts hosted by the wealthy baknang class. [Source: Wikipedia]

The most important Ibaloi feast is the Peshit or Pedit, a grand public celebration typically sponsored by individuals of wealth and prestige. These feasts can last for weeks and involve the ritual sacrifice of dozens of animals.

Traditional Ibaloi attire for men consists of a g-string (kuval), with wealthy individuals wearing a dark blue blanket (kulabaw or alashang) and others using a white one (kolebao dja oles). Women wear a blouse (kambal) and skirt (aten or divet). Decorative items such as gold-plated tooth covers (shikang), copper leglets (batding), bracelets (karing), and ear pendants (tabing) reflect the importance of gold and copper mining. Gold is obtained through lode or placer mining, crushed with stone tools, washed in troughs, and melted into small cakes. Older individuals may display arm tattoos as symbols of prestige.

Ibaloi Mummy Caves and Burial Practices

The Ibaloi are well known for their distinctive mortuary practice of mummification. This process uses saltwater to slow decomposition, while pounded guava and patani leaves are applied to prevent infestation by insects. Drying and preservation may take several months to more than a year, until the body becomes fully hardened.

Ibaloi mummies were placed in caves in central Luzon between 10th and 18th centuries still survive. Honored dead were mummified and and laid to rest in hollowed logs in the caves around what is now the Filipino municipality of Kabayan, 320 kilometers (200 miles) north of Manila.. In the old days, old or seriously ill Ibaloi who believed to be were on the verge of dying sometimes prepared their bodies for mummification by drinking a brine solution to cleanse their bodies. Thirty-two Ibaloi mummies are in four caves near Kabayan,

For eight days, the indigenous people from Benguet blindfold the dead and then sit it on a chair that is placed next to a house’s main entrance. The arms and legs are held in the sitting position by means of tying. A bangil rite is performed by the elders on the eve of the funeral, which is a chanted narration of the biography of the deceased. During interment, the departed is directed towards heaven by hitting bamboo sticks together. +++

See Separate Article: MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, SAGADA HANGING COFFINS, CAVES factsanddetails.com

Tattooed Ibaloi Mummies

The Ibaloi are famous for their tattoos. An illustration from around 1896 shows the Ibaloi burik tattoo pattern, a distinctive cultural marker. A rare photo of an Ibaloi mummy reveals the mummy in a fetal position, its body covered with geometric tattoos. The intricately tattooed body belongs to Apo Annu, a tribal leader from the Benguet province of the Philippines who died more than 500 years ago. Archaeologists believe people from this region earned their tattoos—typically geometric shapes and animals—in battle. [Source: Erin Blakemore, National Geographic, June 5, 2023]

Archaeology magazine reported: In life, these ancient people had won the right to be covered in spectacular tattoos depicting geometric shapes as well as animals such as lizards, snakes, scorpions, and centipedes. “According to nineteenth-century ethnographic accounts, Ibaloi head-hunting warriors revered these creatures as ‘omen animals,’” says Smithsonian anthropologist and tattoo scholar Lars Krutak. “The sight of one before a raid could make or break the entire enterprise.” After successfully taking the head of an enemy in battle, a warrior would have these propitious animals permanently etched onto his body. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2013]

Some Kabayan mummies also feature less fearsome tattoos, such as circles on their wrists thought to be solar discs, or zigzagging lines variously interpreted as lightning or stepped rice fields. “All these tattoos seem to depict the surrounding environment,” says Krutak, who notes that the increased attention paid to the mummies in the last decade has helped fuel a resurgence in traditional tattooing, which had largely died out. Today, thousands of people tracing their descent to the ancient Ibaloi wear designs on their skin modeled after those of their ancestors.

Kalanguya (Ikalahan)

The Kalanguya, also known as the Ikalahan, are a small indigenous group inhabiting the Sierra Madre, Caraballo, and eastern Cordillera mountain ranges, with their main population concentrated in Kayapa, Nueva Vizcaya. Although often classified among the Igorot or “mountain peoples,” they identify themselves as Ikalahan, a name derived from the trees native to the Caraballo Mountains. Their population was recorded at 96,619 in 2010. Historically, the Kalanguya language was widely spoken across areas that now include Benguet, Nueva Vizcaya, Ifugao, Mountain Province, and parts of Nueva Ecija. Scholars such as Felix M. Keesing suggest that, like other upland groups, the Kalanguya migrated into the highlands to avoid Spanish colonial control in the lowlands. [Source: Wikipedia]

Kalanguya society is divided into two main social classes: the wealthy (baknang or kadangyan) and the poor (biteg or abiteng). Their subsistence economy traditionally centers on swidden or slash-and-burn farming (inum-an), particularly the cultivation of camote and gabi. Social authority rests with the elders (nangkaama), and communal decisions are reached through the tongtongan council. Ritual feasts include the keleng, held for healing, ancestor remembrance, and other occasions, as well as the more elaborate padit, which may last up to ten days.

Traditional Ikalahan houses are rectangular, raised three to five feet above the ground, and built for nuclear families. Roofing is made from reeds or cogon grass, walls from bark or wooden slabs, and floors from palm strips. Each house usually has a single main room, one window and door, and a separate guest or sleeping room (duwag) opposite the kitchen. Two stone stoves are used, one for household cooking and another for preparing pig feed. Pigs are kept beneath the house or in nearby pens, while household utensils are stored on wooden or rattan shelves.

Music is an important part of Kalanguya life, especially during celebrations. Bamboo-based instruments are common, with gongs (gangha) as the primary instruments, accompanied by drums. Other instruments include a native guitar (galdang), the struck vibrating pakgong, and the Jew’s harp (ko-ling). Men have traditionally worn a loincloth (kubal) and carry deer-hide backpacks (akbot), usually along with a bolo when leaving home. Women wear woven skirts (lakba) and matching blouses, and carry baskets (kayabang) for farm work. Common ornaments include brass coiled bracelets (gading or batling).

Kalanguya subsistence includes limited cultivation of talon rice, alongside camote, gabi, beans, bananas, ginger, and various fruit trees. Their diet features wild game such as pigs, deer, birds, wild chickens, and fish. Domesticated pigs serve both as food and symbols of wealth, while chickens are reserved mainly for special situations such as childbirth or illness rather than everyday consumption.

Kankanaey

The Kankanaey live in the mountains of the Cordillera Central in western Bontok Province in north-central Luzon. Also known as the Igorot, Kankanay, Katangnang, Lepanto Igorot, Northern Kankanao Central Kankanaey, Kakanay, Kankanai, and Southern Kankanai, they are closely related to the Bontoc and Ibaloi. The are famous for their stone-wall rice terraces and unusual burial practices. [Source: Mayra Diaz,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Kibungan Kankanaey population in the early 2020s was 280,000. Most practice traditional animist religions and 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with most of these being Protestant Evangelicals. In 1981 the Lepanto Igorot numbered approximately 60,000, of whom some 20,000 resided in Sagada municipality. ~

Kankanaey villages with 300 and 2,000 people that are organized in a series of wards (“dapay”) that are similar to Bontoc “ato”, each of which as its own ceremonial platform and boys and girls sleeping houses. Their homes are two or three-stories high and was made of wood and have thatched roof and an enclosed area underneath used for sleeping, cooking and eating, the upper level is used as a granary. Sweet potatoes are grown in fields and pigs are kept in pens. Stone-walled rice terraces are set up near streams. They keep pigs, chickens ,dogs and water buffalo, some of which are sacrificed in characterized ceremonies.

Kankanaey Life

Men have traditionally done the heavy labor such as preparing the rice terraces, dams and ditches, hunt and fish, secure timbers for house, do metal work and weave baskets and help with the cooking and child rearing. The women tend the crops on the fields and repair the terraces and do the bulk of the childrearing and housekeeping chores. [Source: Mayra Diaz,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Marriage is an important social event and the focus of a number of different ceremonies and rituals. . Most are contacted through the “olag” (girls’ dormitory), generally after a period of experimental mating. Wealthy families sometimes betroth their children at birth to establish unions with other families. These families are expected to hold elaborate and expensive wedding celebrations that a large group can enjoy.

Newlywed have traditionally been given the house f one of the parents and the parents moved somewhere else. Children are essential to making a marriage last. If no children are born certain ritual are held to encourage births, If that doesn’t work the marriage often breaks up. As rule marriage is monogamous and adultery is taboo, with severe punishments including the death of children.

In Sagada, social organization is based on six major bilateral descent groups, or families, tracing ancestry to prominent founding figures. These are subdivided into smaller groups descended from a male ancestor several generations back. While these groups do not directly regulate marriage, they perform ceremonial functions and collectively manage certain natural resources through appointed wardens, though they do not control rice lands. In addition, a formally recognized personal kindred—extending to third cousins—defines obligations related to vengeance, compensation, and the acceptable range for marriage outside the group.

Old men pass on the traditions of the village and the people to the younger generation by teaching boy legends, songs, ceremonies and prayers. There are main Sagada groups: the Dagdag and Demang. They are very competitive and there is evidence they used to bury each other’s dead, Every year the village boys from each group engages in a “rock fight.” Each group has its own sacred grove, guardian spirits and sacred springs.

Kankanaey Religion and the Hanging Coffins of Sagada

Like the Bontoc, the Sagada have deep reverence for deceased ancestors (“anitos”) and put great emphasis death ceremonies to make sure the dead are given a good sending off and make their way to the “house of anintos” so they don’t stick around as ghosts restless ghost and bother the living. [Source: Mayra Diaz,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Full funeral ceremonies are conducted only for married people. Full rites including placing the corpse of the deceased on a death chair and coffin burial in ancestral caves or stone-lined mausoleums. Infants and young children are buried in clay jars nest to the house without any ceremony or rites. There is a lengthy mourning period, which is slowly mitigated with a series if animal sacrifices. Elders, held in high esteem and considered keepers of tribal traditions, are given extra special burials and the mourning period for them is longer and greater care is taken to look after their spirits.

Hanging coffins are an ancient funeral tradition in northern Luzon of the Kankanaey people an, Igorot tribe in which the elderly carve their own coffins and the dead are suspended from the sides of cliffs. In several areas, coffins of various shapes can be seen hanging from vertical mountain faces, in caves, or on natural rock projections. The coffins are small because the deceased are placed in the fetal position. This is because they believe that people should leave the world in the same position as they entered it. The coffins are high off the ground because the Kankanaey want the spirits of the dead to go up to Heaven, and the closer they are to heaven the better. [Source: Karl Grobl, CNN, May 5, 2012]

See Separate Article: SAGADA HANGING COFFINS, MUMMIES, CAVES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026