BUGKALOT

The Bugkalot are a forest people that live in the southern Sierra Madre and Caraballo mountains on the eastern side of Luzon in the Philippines. Also known as Ilongot, Ibilao, Ibilaw, Ilungut, Ilyongt and Lingotes, they reside primarily in the provinces of Nueva Vizcaya and Nueva Ecija, as well as along the mountain border between the provinces of Quirino and Aurora. They are former headhunters and live in an enclave and have resisted attempts to assimilate them. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993), Wikipedia]

There is some confusion about the Bugkalot name and composition. In the old days they were referred to by outsiders as Ilongot but now Bugkalot is the preferred name. It is also the name of their language. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 97,000 Bugkalot in the early 2020s. According to "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)" there are 18,000 Bugkalot. Estimates from the 1970s put the number of Bugkalot at around 2,500. According to the 2000 census, 1,180 people in Nueva Vizcaya province identified as Bugkalot. Another estimate from 2000 counted 50,786 Bugkalot. The discrepancy between these figures may be attributed to the different criteria used to define a Bugkalot. Almost 30,000 people in Nueva Vizcaya province and over 14,000 in Quezon province were classified as "other indigenous ethnicity" rather than as Tagalog, Ilocano, Ifugao, Ibaloi, Ayangan, or Bugkalot. This suggests that some people classified as "other indigenous ethnicity" may have been Bugkalot who did not identify as such. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Bugkalot tend to inhabit areas close to rivers because they provide food and transportation. They have traditionally lived in an 840-square-kilometer (325-square-mile) area of rolling hills ranging from 0.3 to 900 meters (1,000 to 3,000 feet) above sea level in southern Nueva Vizcaya province. This area is located where the Cordillera Central connects to the Sierra Madre, which runs down the east coast of Luzon. The headwaters of the Cagayan River drain these lands. A group of modernized Bugkalot live along Baler Bay. The surrounding lowlands are settled by Christian Gaddang, Isinai, Tagalog, and Ilocano peoples. ++

Language may be spoken to some degree by approximately 50,000 people. They also speak Ilocano and Tagalog; the latter is spoken in Nueva Ecija and Aurora as much as Ilocano. Linguists estimate that the Bugkalot language has been developing separately from other Philippine languages for over 3,000 years. In comparison, the Bontok and Ifugao languages were one language only 1,000 years ago. One of its peculiarities is its numeral system, which counts as follows: numbers one through five are each expressed by distinct words, while six through nine are expressed as "five and one," and so on. Higher numbers are composed similarly: For example, 49 is "fifty and five and four," and 60 is "fifty and ten." ++

RELATED ARTICLES:

ILONGOT IN THE 1910s factsanddetails.com

KALINGA: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

KALINGA IN 1910 factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, PINE FORESTS, BONTOC RICE TERRACES factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

Bugkalot History

Although they share certain affinities with the swidden-farming (shifting-cultivation) northern Cordillera peoples such as the Kalinga and Ifugao, the Bugkalot are set apart even from these groups by their extreme egalitarianism and relative cultural simplicity—traits that in some respects recall those of the Dumagat Negritos, with whom some Bugkalot have intermarried. It remains an open question whether Bugkalot culture (the people call themselves Bugkalut; the lowland term Bugkalot derives from ’irungut, meaning “forest people”) represents a largely unchanged survival of an ancient north Luzon tradition, or instead a streamlined remnant of a once more complex culture reduced to its essentials through prolonged self-isolation. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Although Spanish soldiers and missionaries had reached the upper Cagayan Valley by the early seventeenth century, they exerted little influence on the Bugkalot. Their reputation as a fierce, wild, and unsubjugated people persisted well into the American period and even during the Japanese occupation, when as much as one third of the population is said to have died resisting the new invaders. Unlike other independent tribes, the Bugkalot also largely avoided trade relations with lowlanders, which many neighboring groups regarded as indispensable. ++

This relationship with the lowlanders is succinctly expressed in a Bugkalot creation myth recorded by Laurence Wilson in the 1940s. In the myth, the creators and guardians of the world are two quarrelsome brothers, Caín and Abál (the Spanish forms of the biblical Cain and Abel). Caín is the ancestor of the Bugkalot, who, like him, are killers and headhunters. Abál, by contrast, is the ancestor of the lowlanders, who inherit from him mastery over water buffalo and other domesticated animals. In the Bugkalot version, Abál is the stronger brother, a fact that explains the superior power of the lowlanders. ++

In recent decades, the Bugkalot’s isolation has been brought to an end by the arrival of the logging industry and by the construction of airstrips associated with the New Tribes Mission (Protestant). At the same time, Christian farmers from other ethnic groups have steadily encroached upon Bugkalot territory. Violent confrontations between Bugkalot and settlers have been frequent and attracted national media attention in the 1960s. In Nueva Vizcaya province, the Bugkalot now constitute only a tiny fraction of the population—less than one-half of one percent in 2000 if only those self-identifying as Bugkalut are counted—although the census category of “Other,” largely composed of indigenous groups from within the province, accounted for 8.2 percent that same year. ++

Bugkalot Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project most Bugkalot practice traditional animist religions and 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with 5 to 10 percent of these being Protestant Evangelicals. Before the 1950s, when Protestants missionaries arrived in their homelands, the Bugkalot had never been exposed to major world religions. Christian holidays are celebrated among Christians. Harvest rituals have traditionally been the only regular communal rites. Others include occasional headhunting and peacemaking rites. [Source: Joshua Project]

Traditional Bugkalot religion revolves around helpful and dangerous supernatural beings. Illnesses are believed to be caused by supernatural beings who lick or urinate on their victims. Shaman preside over curing ceremonies, and spirits are kept away by bathing, smoking and sweeping. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

The Bugkalot acknowledge a wide range of supernatural beings, including a creator–overseer deity associated with the sun and the spirits of ancestors. Their greatest concern, however, centers on nature spirits and spirits that cause illness. The most powerful and feared of these is ’Agimeng, the “companion of the forest,” who guards hunting and headhunting but is also a bringer of disease; his female counterpart presides over cultivated fields. Illness-giving spirits are usually linked to specific landscape features and are identified by characteristic symptoms and the plants believed to cure them. As spiritual familiars, they may also form enduring associations with particular individuals. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Bugkalot Rituals, Shaman and Burial Practices

Dreams may guide individuals to charms for health or hunting, but visions and serious illness more often introduce people to such spiritual familiars. Only a small number go on to become shamans, qualified to diagnose and cure illness, lead special chants, and summon the souls of future headhunting victims. Those healed by a shaman may share in the power of the familiar spirit and are thus able to conduct minor rituals themselves. Other supernatural abilities attributed to individuals include sucking out disease and divining the future with a bow. ++

Illness is commonly believed to result from spirits licking or urinating on a victim, though it may also be caused by deceased ancestors who yearn for the company of the living, or by offended guardian spirits of fields and forests who feel mistreated by humans. Healing rites begin by invoking the spirits and then expelling them through the manipulation of plants—some 700 varieties are said to be used. These rites may also involve threatening the spirits, blowing them away, steaming them out, bathing to wash them away, beating them out, or drinking substances to purge them. In some cases, a contagious plant associated with the illness is burned or beaten to eliminate the symptoms, or the sickness itself is ritually turned back upon the spirit that caused it. ++

The Bugkalot bury their dead in a sitting position. Women who die in childbirth or through violent means have their hands bound to their feet to prevent their “ghosts” from wandering. Each person is believed to possess a spirit that leaves the body during sleep and survives death as an entity dangerous to the living. Funerary rites are therefore intended to banish the spirit of the deceased through ritual sweeping, smoking, bathing, and invocation. The corpse is wrapped in bark or placed in a box and buried near the home, either seated or curled on the right side, with valuable goods hung on a post at the foot of the grave. The bodies of young children, by contrast, are wrapped in bark and placed high in trees, since close contact with the earth is thought to be painful and dangerous for them. ++

Bugkalot Society

There is no formal leadership in Bugkalot society. Informal leadership lies with sons and brothers who have oratorical skills and have acquired knowledge of myths, ceremonies and genealogies. The oratorical skills are known as purung, which women reportedly can not understand.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Since Bugkalot society has no hierarchy in which superiors command the obedience of inferiors, each man must rely on his personal eloquence to persuade his fellows to follow his desired course of action. At public gatherings, a man attempts to move those present toward a consensus to which they may already be inclined, as he has learned through prior discussions with each person. Consensus is essential since no sanctions can be applied to compel anyone to do anything. In conferences between settlements, such as peacemaking conferences, the most adept purung practioners from one settlement compete with their counterparts from the other settlement. Bride-price negotiations provide an opportunity for parties to seek redress for past grievances or compensation for previous bride-prices. ++

Traditionally, disputes and grievances were settled through the exchange of betel, oaths involving salt, and animal sacrifices. Disputes were sometimes settled by giving offenders ordeals to establish their innocence. More often than not they evolved into feuds settled through head hunting raids. A death in a household required a young man in that house avenge it. A pig was sacrificed when headhunters return. Some feuds are settled with negotiations and exchanges, Many go on for a long time.

In situations that require public persuasion—such as debates over bride-price—individuals often find it advantageous to claim affiliation with one or more behrtan. At its simplest, a behrtan is a cluster of several settlements sharing a collective name, typically derived from a landmark, plant, color, or place, and speaking a distinct dialect. It is the local group within which marriage most commonly occurs and, in the past, whose members may be subject to revenge (head-taking) for the offense of one of their own. A person inherits the right to claim ties to a behrtan through either parent and may assert connections to as many as four, corresponding to the four grandparents. Women generally prefer to identify with their mother’s behrtan, while men favor their father’s and seek to transmit it to their children—a right that becomes possible only after the bride-price has been fully paid. It should be emphasized that the behrtan is not a corporate or fixed social unit; more often, it functions as a flexible way of defining an interest group for a particular moment, such as the opposing sides in bride-price negotiations. Thus, a newcomer to a discussion may assert solidarity with one side by claiming a behrtan connection that cannot be substantiated genealogically. ++

Bugkalot Headhunting

Renato Rosaldo studied headhunting among the Bugkalots in his book “Ilongot Headhunting, 1883-1974: A Study in Society and History”. He said that headhunting raids were often associated with bereavement and rage over the loss of a loved one. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the old days, every male Bugkalot was expected to engage in headhunting, ideally before marriage, and most men in the recent past had done so. Unlike some other headhunting societies, the Bugkalot did not take heads to magically enhance soil fertility, to accumulate personal spiritual power, to gain social prestige, or solely to pursue vendettas. Instead, a man took a head in order to “relieve his heart” of anxiety, which might stem from a death within his household or from an unresolved feud. Often he made a binatan, an oath of personal sacrifice—for example, abstaining from rice from the granary or refraining from sexual relations until he had taken a head. Successfully taking a head entitled a young man to wear prestigious ornaments such as cowrie shells, feathers, and red hornbill decorations. While the act did elevate his standing, because all men underwent the same experience it ultimately reinforced the society’s overall egalitarianism. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++] ++

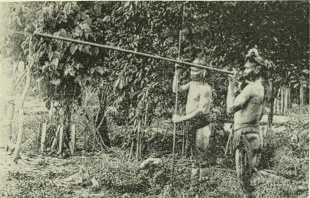

Men hunted heads either alone or in raiding parties that could number up to forty individuals. Before departure, they gathered in front of a house, where a shaman summoned the souls of the intended victims into a bamboo container. In the forest, the men listened for bird omens and sometimes played instruments associated with death, such as a violin or reed flute. Distinctions were sought in being the first to strike or shoot, to reach a fallen body, to sever a head, or to fling it away. The heads themselves were not kept, unlike in cultures where skulls were preserved as symbols of status or sources of spiritual power, though hands might be brought back for children to chop apart. The return of the headhunters was marked by communal celebration, including singing, dancing, and the slaughter of a pig. ++

Encroachment on Bugkalot territory by other ethnic groups increasingly provoked violent confrontations between the Bugkalot and incoming settlers and between Bugkalot groups squeezed closer together. Peace between hostile groups was established through a series of debates and exchanges, after which members of the opposing sides might visit one another, intermarry, or even conduct joint raids against other groups. If no intermarriage occurred, however, hostilities typically resumed within two generations. ++

Bugkalot Family and Gender

Traditionally, one to three nuclear families lived under a single roof, each maintaining its own hearth and sleeping space. These households usually consisted of the parents’ family together with the families of the youngest married daughters. Sons left the household upon marriage, while daughters remained in the parental home, departing only when younger sisters married and brought their husbands in. A married couple could return to the man’s natal community only after he had fully paid the bride-price. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Bugkalot kinship terminology displays several distinctive features. A single term, ’apu, is used for grandparents, parents-in-law, and children-in-law, while another term, ’aum, refers both to a sibling’s spouse and to a spouse’s sibling. One is prohibited from addressing an ’aum by name and is required to treat him or her with particular respect. Although sexual relations with an ’aum are forbidden, it is common for a surviving spouse to marry a sibling of the deceased partner. ++

Deliberations aimed at reaching consensus on collective action were traditionally regarded as an exclusively male domain, since it was believed that women neither understood nor were capable of purung (oratorical skill). According to the 2000 census, among those who self-identified as Bugkalut, men slightly outnumbered women (51.7 percent). In Nueva Vizcaya as a whole, women exceeded men by a substantial margin in college attendance and degree attainment, while at the elementary level—arguably a more relevant measure for the Bugkalot—completion rates were lower for girls than for boys (53.3 percent of elementary school graduates were male, compared with males comprising only 51 percent of the population). Women tended to invoke connections with their mother’s behrtan, whereas men more often emphasized ties to their father’s. ++

In her 1980 study of the Bugkalots, Ivan Salva described "gender differences related to the positive cultural value placed on adventure, travel, and knowledge of the external world." Bugkalot men more often visited distant places than women did. They acquired knowledge of the outside world and amassed experiences there. Upon returning, they shared their knowledge, adventures, and feelings in public oratories to pass on their knowledge to others. As a result of their experiences, the Bugkalot men received acclaim. Because they lacked external experience on which to base knowledge and expression, Bugkalot women had inferior prestige. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bugkalot Marriage and Sex

In the past young men were expected to engage in a successful head hunt before marriage. Prospective marriage partners usually exchange gifts, work together in the fields and have sex before the get married. Pregnancy speeds up the process which is not finalized until the two families who are going to be unified have settled all their disputes. Marriages are usually monogamous and second cousins are preferred partners. Because leadership within a community is usually provided by a particular set of brothers, it is also common for that group of brothers to marry a corresponding set of sisters, who are often their close cousins.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Adolescents of the opposite sex may exchange betel and sleep together before being publicly recognized as a couple. Such informal relationships—marked by occasional field labor by the male partner, the exchange of gifts, and sexual relations—typically precede formal marriage negotiations. A pregnancy often heightens tensions between the two families, provoking both gift-giving and threats of violence, which are usually resolved only through marriage. ++

The langu, or bride-price, is intended to appease the anger of the woman’s kin and may include payments to members of distant behrtan who can claim a connection to her. The negotiation and extended payment of the langu provide an opportunity for kin to voice grievances and resolve them by compensating offended parties with langu goods. The process begins with a pu’rut, an initial and often hostile confrontation between the man’s and the woman’s sides. Subsequent langu installments may consist of guns, bullets, metal pots, cloth, jewelry, and knives. Over a series of pi’yat meetings, the man’s party presents meat and goods to the in-laws and ultimately “buys the woman.” The woman’s side then reciprocates with an ’arakad, bringing pounded rice and liquor to the man’s kin. ++

Bugkalot Life and Customs

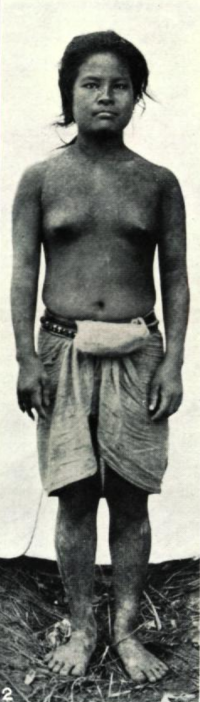

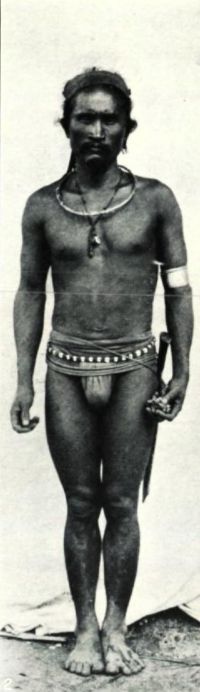

The Bugkalots have traditionally worn plain or dark blue or black loincloths with a colored band around the hips. A long red or black band was tied around the hands and no shoes were worn. Traditional Bugkalot clothing was made from lengths of bark pounded to the consistency of soft leather. Some men wore a length of cloth passed between the legs and secured with a belt of rattan or brass wire. Women still wear a short sarong (waist to knees) along with earrings, bead necklaces, and brass wire spiraling over the arms. Children sometimes go naked. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Girls traditionally got their ears pierced as babies, and boys got theirs pierced before they reached their teens. At age 15, boys and girls could choose to have their teeth filed and blackened for beauty purposes. Feasting and oath-taking accompanied the procedure. Teeth filing used to an act of initiation into adulthood. In 1947, Laurence Lee Wilson wrote: “Sometime in their middle teens, the maidens and youths have their teeth filed down. A group of her boyfriends will rally round a girl in her house and hold her down tight while one cuts her teeth down - no matter how much she screams from the excruciating pain. After the operation, one lad will take a pencil-sized twig from a guava tree or the stem of a batac plant, heat it in the fire, and rub the warm bark on the teeth: thus, stopping the blood and easing the pain. Thereafter the shortened teeth are strong for chewing - even bones, and picking the teeth after eating is unnecessary. When it is all over, wreaths are hung up and a gala time is had with basi [fermented wine], chicken, and rice. [Source: Teresita R. Infante, [Source: kasal.com ^]

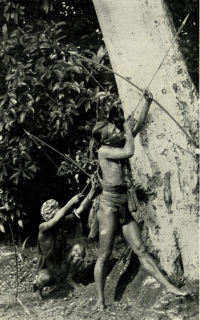

In the old days, members of the Bugkalot tribe were probably the closest things to real life Tarzans. They were pictured in National Geographic using 12-meter-long (40-foot) pieces of rattan to travel through the thick jungle by swinging from tree to tree. One end of the rattan vine had a hook on it which hooked around a tree limb; the other end had a loop to hold on to. Holding on to the vine with their hands and toes the tribesmen are to able to swing from one branch to another. By clinging to one tree and casting the flexible “rope” to catch another, they could travel rapidly through dense forest. The technique was used when cutting branches from trees to be felled in clearing new fields. ++

Nueva Vizcaya province is relatively poor compared to other provinces in the Cagayan Valley region. In the 2000 census, only 50.8 percent of houses in Nueva Vizcaya were supplied with electricity, compared with 70 percent in neighboring Isabela province. Similarly, 15.3 percent of households relied on springs, lakes, or rivers for water, in contrast to just 1.9 percent in Isabela. The Bugkalot's isolation has meant that they have not received modern education as most other Filipinos have, including lowlanders and highlanders, Christians and non-Christians alike. However, Protestant missions have introduced some Bugkalot to modern education. ++

Bugkalot Villages, Houses and Food

The Bugkalot have traditionally lived a semi-nomadic life in groups with around 180 or so members. Each groups is made up of several settlements, which in turn have four to nine households, with five to 15 nuclear families and 40 to 70 individuals. Settlements are set up by their fields and are moved whenever they clear new fields. In the past houses were seldom built directly next to one another, though they were always within calling distance. Over time, as households abandoned old fields and opened new ones, dwellings were moved closer to the newly cultivated land, causing settlements to become increasingly dispersed. Conversely, when long-fallow fields were reclaimed, houses might again draw nearer to one another. The only consistently concentrated settlements were clusters of houses built near the airstrips of the New Tribes Mission. ++[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Houses have traditionally been constructed on pilings about 2 to 5 meters (6–15 feet) above the ground, with walls of woven grass or bamboo. A typical house (kamari) had a square floor plan and was topped by a pyramidal or single-ridged roof. The interior consisted of an unpartitioned central space bordered by a slightly raised wooden platform that held the hearths—up to three in a single house, one for each resident nuclear family. Smaller, temporary field houses (’abun) were also built near cultivated areas. ++

Rice formed the staple of the Bugkalot diet and was typically eaten with vegetables, while root crops served as a secondary source of starch. A variety of wild plants—including fruits, ferns, and palm hearts—were also gathered for food. Animal protein was obtained mainly from wild pigs, deer, and fish. The Bugkalot did not eat the pigs and chickens they raised for sale to lowlanders, however, as domestic animals were believed to consume excrement and were therefore considered unfit for human consumption. Dogs, which were essential for hunting, lived inside the house and were never eaten. ++

Although eating with the hands from flat leaves is common throughout Southeast Asia, the Bugkalot also fashioned disposable cups for vegetable broth from anahao leaves. The Bugkalot produced basi, an alcoholic drink made from sugarcane, and men frequently gathered for communal drinking sessions. ++

Bugkalot Folklore, Music and Sports

Bugkalot have traditionally entertained themselves by telling folktales (dimolat), which exist in both short and long forms. Short tales are told by individuals resting briefly together or encountering one another by chance, while the long form is reserved for extended evenings or periods of heavy rain. These longer narratives are typically sung by an elderly woman or man with a deep store of knowledge and freely blend supernatural, human, and animal characters, often emphasizing practical jokes. Storytellers embellish the core plot with repetitions and minor incidents—frequently for comic effect—and elongate final syllables or insert nonsensical words to fit a fixed melody. For listeners, the pleasure lies as much in the manner of performance as in the story itself. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Musical instruments include bamboo flutes, brass gongs, a bamboo-tube zither, and a handmade violin- or guitar-like instrument with a body of bark and animal skin and strings made from women’s hair. Young men play these instruments while courting young women. Social gatherings commonly feature antiphonal singing and a variety of dances, including group dances performed by women, solo dances by men, and dances in which men beat handheld gongs. ++

Traditionally, the Bugkalot have had no craft specialists. Each man made his own knives, hoes, and picks and wove his own rattan baskets, while each woman wove and sewed clothing for her family. Children’s play reflected gendered patterns: girls played with rag dolls, while boys engaged in shooting contests with miniature bows and arrows made by their fathers when they reached about four years of age. Boys also enjoyed climbing trees and playing games of tag among the branches. ++

Bugkalot Work and Economic Activity

The Bugkalot are primarily in slash-and-burn agriculturalist, hunters and fishermen. They grow maize, manioc, rice, tobacco, sugar and vegetables and moves their fields once a year. Fields cleared from virgin forest are used for five years and left fallow for eight years. The men hunt with dogs several times a week and all meat is shared equally among the all households and consumed immediately. Sometimes longer hunting trips take place. Here the meat is dried. Fish are taken with nets, traps, spears and poison. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Bugkalot have traditionally cultivated dry rice, maize, and cassava together in one rotation in their swidden fields. After the harvest, they plant tobacco and vegetables in same fields. As the fields approach abandonment, they are given over to sweet potatoes, bananas, and sugarcane. Depending on its fertility, a given field may be worked from one to five years. Once the soil becomes depleted, farmers move on to clear another plot of land from the forest, sometimes traveling up to 32 kilometers (20 miles) away. Land has traditionally belonged to whoever clears it for use, but it can be reopened and cultivated by anyone at a later date. Having little inherited property, the Bugkalot generally do not bequeath agricultural lands. Due to the low population density in their territory, wild land is always available. Collecting forest plants also contributes to their diet. ++

The Bugkalot also collect forest products such as rattan for their own use and to trade, forge their own knives, picks and hoes. Item they obtain through trade include bullets, cloth, knives, liquor and salt. Much of the trading is done to obtain goods for bride payments. The Bugkalot trade baskets and metalwork among themselves, but most such wares circulate as part of bride prices or gifts among relatives. Bugkalot barter dried meat, fawn fawns, pigs, and chickens for bullets, liquor, cloth, salt, and knives with lowlanders. To facilitate these exchanges, Ilocano or Tagalog traders come to the Bugkalot border, and the Bugkalot travel to lowland towns. ++

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026