BONTOC

The Bontoc is a group of former headhunters that has traditionally lived in the steep gorge region along the upper Chico River system in the central and eastern parts of Central Mountain Province of northern Luzon. Also known as the Bontok, Bontoc Igorot, Guianes, Igorot, they have traditionally lived by hunting, fishing and farming. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The term "Bontoc" is used by linguists and anthropologists to distinguish speakers of the Bontoc language from neighboring ethnolinguistic groups. Some Bontoc Natonin and Paracelis identify themselves as Balangaos, Gaddangs or Kalingas, The Western and Eastern Bontok languages are closely related to Kankanai (Lepanto), which is part of a subgroup within the Northern Luzon Group of Philippine languages.

The Bontok are the second-largest ethnolinguistic group in Mountain Province and have historically settled along the riverbanks. They occupy a rugged, mountainous landscape, particularly along the Chico River tributaries. The surrounding highlands are rich in mineral resources, including gold, copper, limestone, and gypsum, with gold traditionally mined in the municipality of Bontoc. The Chico River is a source of sand, gravel, and white clay, while the forests of Barlig and Sadanga supply rattan, bamboo, and pine. [Source: Wikipedia]

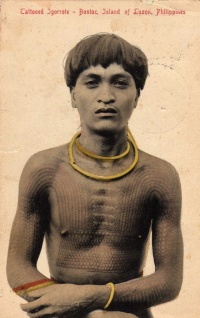

The Bontoc speak Bontoc and Ilocano. They are known for distinctive tattoo traditions. Three main types of tattoos were recognised: chak-lag , a chest tattoo worn by head-takers; pong -o, arm tattoos for both men and women; and fa -tĕk, a general term for other tattoos on either sex. Women, however, were tattooed only on the arms.

Total population of Bontoc is 72,084 according to the 2020 census. The population of Mountain Province is 149,775 as of July 2024. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 26,000 Central Bontoc and 3,200 Southwestern Bontoc in the early 2000s. The 1960 census recorded a Bontok population of 78,000. In the mid-1980s, the number of Western and Eastern Bontok speakers was estimated at 30,000 and 6,000, respectively. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, PINE FORESTS, BONTOC RICE TERRACES factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Book: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks (1905)

Bontoc Society

Bontoc social organization was traditionally organized around village wards made up of roughly 14 to 50 households. In the past, young men and women lived in separate dormitories while continuing to take their meals with their families, a practice that has declined in recent decades, especially where of Christianity has taken hold. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Bontoc place strong emphasis on kinship and collective identity, known as sinpangili, which is rooted in shared ancestry, a common history of defending the community from intruders, and participation in communal rituals tied to agriculture and province-wide concerns such as natural disasters. Kinship groups primarily function to regulate property ownership and marriage, but they also serve as the foundation for mutual aid and cooperation among members.

Bontoc society traditionally recognized three broad social classes: the kakachangyan (wealthy), the wad-ay ngachanna (middle class), and the lawa (poor). Members of the wealthy class demonstrated their status by sponsoring feasts and assisting those in need, while poorer individuals often worked as sharecroppers or laborers for the rich. In addition, the Bontoc had a distinct caste known as the kadangyan, whose members held specialized leadership roles, practiced endogamous marriage, and wore distinctive clothing.

Bontoc women have a reputation for being hard workers. Young women traditionally slept in a common sleeping quarter [olog], to which young men are freely invited. One anthropologist described the custom as a "calculated to emphasize the fact and significance of puberty." [Source: Teresita R. Infante, [Source: kasal.com ^]

Bontoc Life

Bontoc villages are organized in wards called “ato”. Each village has between six and 19 ato and each ato has 14 to 50 houses. The ato are set around a stone platform, where headhunting ceremonies were held, and an unmarried girls dormitory and an unmarried boys dormitory, which also serve as a club house and council room. Each ato is governed by a council of elders. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Bontoc have traditionally had three main indigenous dwelling types: the family residence (katyufong), female dormitories (olag), and male dormitories. These living spaces were closely linked to agricultural life and complemented by related structures such as rice granaries (akhamang) and pigpens (khongo). Traditionally, all buildings were roofed with inatep, or cogon grass. Bontoc homes were also well equipped with everyday utensils, tools, and weapons, including cooking implements; farming tools such as bolos, trowels, and plows; and bamboo or rattan fish traps. [Source: Wikipedia]

Rice is the primary staple of the Bontoc diet. During the dry months from February to March, when rainfall is limited, camote, corn, and millet serve as substitutes. The Bontoc also catch and gather fish, snails, and crabs for both household consumption and sale. In earlier times, men typically carried tobacco and matches when hunting wild deer and pigs. Forest resources were likewise important, with people collecting rattan, edible fruits, beeswax and honey, as well as wild plants used for food or ornamentation. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Bontoc use dams, diverted streams and wooden troughs to irrigate agricultural land. The entire community participates in the construction and maintenance of the irrigation system. In the old days, dogs were used to hunt wild buffalo and wild pigs were trapped in pits. Snares are still used to trap birds and cats. Fishing is done by diverting streams to catch fish in nets and traps. Domestic animals include pigs, water buffalo and cats. ~

Bontoc Marriage

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote in 1905: The ethics of the group forbid certain unions in marriage. A man may not marry his mother, his stepmother, or a sister of either. He may not marry his daughter, stepdaughter, or adopted daughter. He may not marry his sister, or his brother’s widow, or a first cousin by blood or adoption. Sexual intercourse between persons in the above relations is considered incest, and does not often occur. The line of kin does not appear to be traced as far as second cousin, and between such there are no restrictions. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Rich people often pledge their small children in marriage, though, as elsewhere in the world, love, instead of the plans of parents, is generally the foundation of the family. In February, 1903, the rich people of Bontoc were quite stirred up over the sequel to a marriage plan projected some fifteen years before. Two families then pledged their children. The boy grew to be a man of large stature, while the girl was much smaller. The man wished to marry another young woman, who fought the first girl when visited by her to talk over the matter. Then the blind mother of the pledged girl went to the dwelling, accompanied by her brother, one of the richest men in the village, whereupon the father and mother of the successful girl knocked them down and beat them. To all appearances the young lovers will marry in spite of the early pledges of parents. They say such quarrels are common.

If a man wishes to marry a woman and she shares his desire, or if on her becoming pregnant he desires to marry her, he speaks with her parents and with his. If either of her parents objects, no marriage occurs; but he does not usually falter, even though his parents do object. They say the advent of a babe seldom fails to win the good will of the young man’s parents. In the case of the girl’s pregnancy, marriage is more assured, and her father builds or gives her a house.

The olag is no longer for her. In her case it has served its ultimate purpose—it has announced her puberty and proved her powers of womanhood. In the case of a desire of marriage before the girl is pregnant she usually sleeps in the olag, as in the past, and the young man spends most of his nights with her. It is customary for the couple to take their meals with the parents of the girl, in which case the young man gives his labors to the family. The period of his labors is usually less than a year, since it is customary for him to give his affections to another girl within a year if the first one does not become pregnant. In other words their union is a true trial union. If the trial is successful the girl’s father builds her a dwelling, and the marriage ceremony occurs immediately upon occupation of the dwelling.

The people of Bontoc say they never knew a man and woman to separate if a child was born to the pair and it lived and they had recognized themselves married. But, as the marriage is generally prompted because a child is to be born, so an unfruitful union is generally broken in the hope that another will be more successful. If either party desires to break the contract the other seldom objects.

If they agree to separate, the woman usually remains in their dwelling and the man builds himself another. However, if either person objects, it is the other who relinquishes the dwelling—the man because he can build another and the woman because she seldom seeks separation unless she knows of a home in which she will be welcome. Nothing in the nature of alimony, except the dwelling, is commonly given by either party to a divorce. There are two exceptions—in case a party deserts he forfeits to the other one or more rice sementeras or other property of considerable value; and, again, if the woman bore her husband a child which died he must give her a sementera if he leaves her.

Bontoc Wedding

The Bontoc wedding ritual usually spans several days. It starts with the delivery of the faratong (black beans) from the girl to the bachelor signifying the bride’s intentions to marry. Afterwards, the bride’s family sends out what is known as the khakhu (salted pork) to the groom’s family. This is countered by the sending of sapa (glutinous rice). These food items are distributed to their respective family members, including their relatives. An important rite called insukatan nan makan (exchange of food) follows. Here, one of the groom’s parents, after receiving an invitation, must go to the bride’s house and have breakfast with them. Later, the groom’s parents also invite a bride’s parent for a similar meal. The next step is the farey. The bride and a kaulog (girlfriend) will visit the house of the groom. This is when they ‘start entering each other’s houses’. They will have to leave immediately also, but they will be invited again on the following morning for breakfast. This is the start of the tongor (to align). [Source: kasal.com ^]

The next day, the bride’s parents, bearing rice and salted meat, will go to the groom’s house for the kamat (to sew tight). A kaulug of the bride and the groom’s best friend is likewise invited. The evening will be the start of the karang or the main marriage ritual. This is when the bride and groom are finally declared as a couple to the whole community. The following morning is the putut (to half). Here, only the immediate relatives are invited for breakfast, signifying theend of the ritual. Two days after the putut, the couple can finally live as husband and wife, but may not sleep together for the next five days, known as the atufang period. The atufang serves to validate the marriage. The groom is instructed to bathe in a spring, taking note of every detail that comes his way, such as the characters he meets, weather changes, among others. Should anything peculiar occur, he must make his way to the mountain to cut some wood. The bride, on the other hand, is sent off to weed in the fields. ^

Any untoward incidents serve as warnings that the new couple must postpone their living together or mangmang. The final stage of the atufang involves covering smoldering charcoals with rice husks overnight. The marriage is considered null and void if the fire goes out the morning after. The final step is the manmanok where the bride’s parents invite the groom and his parents and declare that the groom could officially sleep with the bride. This signifies the end of the marriage ritual for most Igorots. An optional lopis (a bigger marriage feast) could be done should the couple’s finances allow. ^

Describing a wedding in 1905, Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: in 1905: The ceremony is in two parts. The first is called “inpake,” and at that time a hog or carabao is killed, and the two young people start housekeeping. The kapiya ceremony follows—among the rich this marriage ceremony occupies two days, but with the poor only one day. The kapiya is performed by an old man of the ato in which the couple is to live. He suggestively places a hen’s egg, some rice, and some tapui in a dish before him while he addresses Lumawig, the one god, as follows: Thou, Lumawig! now these children desire to unite in marriage. They wish to be blessed with many children. When they possess pigs, may they grow large. When they cultivate their palay, may it have large fruitheads. May their chickens also grow large. When they plant their beans may they spread over the ground, May they dwell quietly together in harmony. May the man’s vitality quicken the seed of the woman. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The twoday marriage ceremony of the rich is very festive. The parents kill a wild carabao, as well as chickens and pigs, and the entire village comes to feast and dance. It is customary for the village to have a rest day, called “fosog,” following the marriage of the rich, so the entire period given to the marriage is three days. Each party to the, marriage receives some property at the time from the parents. There are no women in Bontoc village who have not entered into the trial union, though all have not succeeded in reaching the ceremony of permanent marriage. However, notwithstanding all their standards and trials, there are several happy permanent marriages which have never been blessed with children. There are only two men in Bontoc who have never been married and who never entered the trial stage, and both are deaf and dumb.

Bontoc Children

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote:boys have at least two systematic games. One is fûgfûgto, in imitation of a ceremonial of the men after each annual rice harvest. The game is a combat with rocks, and is played sometimes by thirty or forty boys, sometimes by a much smaller number. The game is a contest—usually between Bontoc and Samoki—with the broad, gravelly river bed as the battle ground. There they charge and retreat as one side gains or loses ground; the rocks fly fast and straight, and are sometimes warded off by small basket-work shields shaped like the wooden ones of war. They sometimes play for an hour and a half at a time, and I have not yet seen them play when one side was not routed and driven home on the run amid the shouts of the victors. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The other game is kag-kag-tin?. It is also a game of combat and of opposing sides, but it is not so dangerous as the other and there are no bruises resulting. Some half-dozen or a dozen boys play kagkagtin charging and retreating, fighting with the bare feet. The naked foot necessitates a different kick than the one shod with a rigid leather shoe; the stroke from an unshod foot is more like a blow from the fist shot out from the shoulder. The foot lands flat and at the side of or behind the kicker, and the blow is aimed at the trunk or head—it usually lands higher than the hips. This game in a combat between individuals of the opposing sides, though two often attack a single opponent until he is rescued by a companion. The game is over when the retreating side no longer advances to the combat.

The boys are constantly throwing reed spears, and they are fairly expert spearmen several years before they have a steel-bladed spear of their own. Frequently they roll the spherical grape fruit and throw their reeds at the fruit as it passes.

Bontoc Culture and Arts

Most Bontocs are farmers who have chosen to retain many aspects of their traditional culture despite frequent contact with other groups. In the past Bontoc performed a circular, rhythmic dance that acted out certain aspects of the hunt. This dance was always accompanied by the gangsa, or bronze gong. There was no singing or talking during the dance, and the women participated from outside the circle. The dance was a serious but enjoyable event for everyone involved, including the children. [Source: Wikipedia]

Music is an important part of Bontoc life and is usually played during ceremonies. Songs and chants are accompanied by nose flutes (kalaleng), gongs (gangsa), bamboo mouth organs (affiliao), and Jew's harps (ab-a-fiw). Wealthy families use jewelry made of gold, glass beads, agate beads, or shells to show their status.

Bontoc tattoos are known as fatek. The Bontoc distinguish three main types: chaklag, the chest tattoos of head-takers; pongo, the arm tattoos worn by both men and women; and fatĕk, a general term for other tattoos found on both sexes. Women were traditionally tattooed only on the arms, both to enhance beauty and to signal readiness for marriage. The arms were the most visible parts of the body during traditional dances, and it was widely believed that men would not court women who lacked tattoos. For men, tattoos signified warrior status and marked those who had taken heads in battle. One traditional tattooing technique was the “puncture/cut and smear” method. In this process, the bumafatek (tattooist) first sketched the design on the skin using ink made from soot and water, then pricked the skin with a chakayyum. Soot was subsequently rubbed into the open wounds and worked into the skin by hand to fix the pigment.[8]

In 1912 Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “The afternoon passed listening to stories and incidents like those just given, until it was time to go and see the sports. These, with one exception, presented no peculiarity, races, jumping, tug-of-war, and a wheelbarrow race by young women, most of whom tried to escape when they learned what was in store for them. But the crowd laid hold on them and the event came off; the first heat culminating in a helpless mix-up, not ten yards from the starting-line, which was just what the crowd wanted and expected. The exception mentioned was notable, being a native game, played by two grown men. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

One of these sits on a box or bench and, putting his right heel on it, with both hands draws the skin on the outside of his right thigh tight and waits. The other man, standing behind the first, with a round-arm blow and open hand slaps the tightened part of the thigh of the man on the box, the point being to draw the blood up under the skin. The blow delivered, an umpire inspects, the American doctor officiating this afternoon, and, if the tiny drops appear, a prize is given. If no blood shows, the men change places, and the performance is repeated. The greatest interest was taken in the performance this afternoon, many pairs appearing to take and give the blow. The thing is not so easy as it looks, the umpire frequently shaking has head to show that no blood had been drawn. The prizes consisted of matches, which these highlanders are most eager to get.

Men wear g-strings (wanes) and rattan caps (suklong). Women wear skirts (tapis). Each villages has traditionally specialized in a single craft: baskets, pottery, beeswax, fermented sugar cane juice, spear blades and breech clothes. The Bontoc people traditionally use weapons such as battleaxes (pin-nang/pinangas), knives (falfeg), spears (fangkao), and shields (kalasag). They worked metal themselves and made spear blades with double-piston bellows.

Bontoc Folk Story: Origin of Coling, the Serpent Eagle

According to the Bontoc folktale “Origin of Coling, the Serpent Eagle”: A man and woman had two boys. Every day the mother sent them into the mountains for wood to cook her food. Each morning as she sent them out she complained about the last wood they brought home One day they brought tree limbs; the mother complained, saying: “This wood is bad. It smokes so much that I can not see, and soon I shall be blind.” And then she added, as was her custom: “If you do not work well, you can have only food for dogs and pigs.” [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

That day, as usual, the boys had in their topil for dinner only boiled sweet potato vines, such as the hogs eat, and a small allowance of rice, just as much as a dog is fed. At night the boys brought some very good wood—wood of the pitch-pine tree. In the morning the mother complained that such wood blackened the house. She gave them pig food in their topil, saying: “Pig food is good enough for you because you do not work well.”

That night each boy brought in a large bundle of runo. The mother was angry, and scolded, saying: “This is not good wood; it leaves too many ashes and it dirties the house.” In the morning she gave them dog food for dinner, and the boys again went away to the mountains. They were now very thin and poor because they had no meat to eat. By and by the older one said:

“You wait here while I climb up this tree and cut off some branches.” So he climbed the tree, and presently called down:

“Here is some wood”—and the bones of an arm dropped to the ground.

“Oh, oh,” exclaimed the younger brother, “it is your arm!”

Again the older boy called, “Here is some more wood”—and the bones of his other arm fell at the foot of the tree. Again he called, and the bones of a leg dropped; then his other leg fell. The next time he called, down came the right half of his ribs; and then, next, the left half of his ribs; and immediately thereafter his spinal column. Then he called again, and down fell his hair.

The last time he called, “Here is some wood,” his skull dropped on the earth under the tree.

“Here, take those things home,” said he. “Tell the woman that this is her wood; she only wanted my bones.”

“But there is no one to go with me down the mountains,” said the younger boy.

“Yes; I will go with you, brother,” quickly came the answer from the tree top.

So the boy tied up his bundle, and, putting it on his shoulder, started for the village. As he did so the other—he was now Coling—soared from the tree top, always flying directly above the boy.

When the younger brother reached home he put his bundle down, and said to the woman:

“Here is the wood you wanted.”

The woman and the husband, frightened, ran out of the house; they heard something in the air above them.

“Qu-iukok! qu-iukok! qu-iukok!” said Coling, as he circled around and around above the house.

“Qu-iukok! qu-iukok!” he screamed, “now sweet potatoes and unhusked rice are your son. I do not need your food any longer.”

Bontoc Agriculture and Rice Terraces

Maligcong (near Bontoc) is known for its impressive rice terraces. To get the best view of these, one has to hike up Mt. Kopapey. It takes about 30 minutes of hike from the village to the mountain top. Many hikers try to climb early in the morning so they can get of the sea of clouds breaking up over the terraces. The view of the gently cascading hills engulfed by rice terraces is breathtaking. Mt. Kopapey feeds creeks and springs which supply water to Maligcong Rice Terraces. These creeks join together into a stream that flows the three-level Lipnok Falls.

Sementera is a Spanish word for agricultural field. Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: It must be noted here that all Bontoc agricultural labors, from the building of the sementera to the storing of the gathered harvest, are accompanied by religious ceremonials. They are often elaborate, and some occupy a week’s time. The carabao (water buffalo), hog, chicken, and dog are the only animals domesticated by the Igorot of the Bontoc culture area. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

There are two varieties of sementeras—garden patches, called “pay-yo”—in the Bontoc area, the irrigated and the unirrigated. The irrigated sementeras grow two crops annually, one of rice by irrigation during the dry season and the other of camotes, “sweet potatoes,” grown in the rainy season without irrigation. The unirrigated sementera is of two kinds. One is the mountain or side-hill plat of earth, in which camotes, millet, beans, maize, etc., are planted, and the other is the horizontal plat (probably once an irrigated sementera), usually built with low terraces, sometimes lying in the village among the houses, from which shoots are taken for transplanting in the distant sementeras and where camotes are grown for the pigs. Sometimes they are along old water courses which no longer flow during the dry season; such are often employed for rice during the rainy season. The unirrigated mountain-side sementera, called “fo-ag,” is built by simply clearing the trees and brush from a mountain plat. No effort is made to level it and no dike walls are built. Now and then one is hemmed in by a low boundary wall.

See Separate Article: MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, PINE FORESTS, BONTOC RICE TERRACES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026