IFUGAO SOCIETY

The Ifugao people live in a mountainous region of north-central Luzon around the of town Banaue. They are former headhunters who are famous for their spectacular mountain-hugging rice terraces. Ifugao communities are organized into districts, defined by a ritual rice field, whose owners make decisions about agricultural matters. Social control is exerted through kinship pressure and by “monbaga”, legal authorities and intermediaries whose power rests in their wealth and knowledge of customary laws (“adat”) and genealogy. They levy fines and make decisions about death penalties and were able to mobilize extensive kin networks to enforce their decisions.. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Ifugao have little in the way of a political system or institutionalized community. There are no chiefs or councils. They live in clan groups that extend to the third cousin. Because there was no higher traditional authority to which an Ifugao could appeal for redress, individuals were required to secure justice for themselves, more accurately through their kin groups. When an injury occurred, the kin of the offended party sought compensation from the kin of the offender. Traditionally, the murder of a kin member could be avenged by killing any member of the murderer’s kin group.

MonbagaT witness exchanges, mediate disputes, and sanction offenses. Compensation traditionally took the form of fines paid in valued goods, including livestock such as water buffalo (often sacrificed at the victim’s funeral), as well as blankets, kettles, knives, and clothing. These fines were distributed among the injured party, his or her kin, and the monbaga, and were calibrated according to both the nature and intent of the offense and the relative status of those involved. Thus, a kadangyan offending another kadangyan paid a heavier fine than in a dispute between two tumuk, and heavier still than between two nawatwat; conversely, a kadangyan injuring a social inferior paid less than for harming a peer, while a nawatwat offending a superior incurred a stiffer penalty than if the victim were an equal. ~

Disputes between people from the same local area were usually resolved through the imposition of fines. By contrast, offenses committed against individuals from a different local area more often escalated into feuding, guided by the principle that “might makes right.” Warfare typically involved headhunting, carried out by ambushing isolated members of enemy groups at the edges of their territory. Raids for women and child slaves were also a common feature of such intergroup conflict.

RELATED ARTICLES:

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

Ifugao Classes

Traditionally, Ifugao society has been divided into three classes: 1) kadangyan (aristocrats), 2) tagu (or, or mabitil natumuk, lower middle class), and 3) nawotwot (lower class). The kadangyan distinguish themselves by sponsoring prestigious rituals, such as the hagabi and uyauy. The tagu are economically stable but unable to host such feasts. The nawotwot typically own little land and work for the upper classes as farmers and in other service roles. In recent decades, a new category of wealthy individuals emerged among the Ifugao. Known as bacnang—a term borrowed from Ilocano meaning “rich”—these were people who accumulated wealth through non-traditional means, mainly commercial and agricultural enterprises such as owning hotels or restaurants, which generated substantial cash income. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Ifugao classes are based on wealth traditionally defined in terms of rice land, water buffalo and slaves. Kadangyan are expected to guide the village about moral and judicial matters and lend money. Their houses are identified by a hardwood bench described below which sits against the stilts. In addition to footing the bill for festivals, they display their wealth and possess important objects such as hornbill headdresses, gold beads, swords, gongs and antique Chinese jars. The definitive marker of kadangyan status was the hagabi, a massive hardwood lounging bench placed beside the house. To install a hagabi, an aspiring kadangyan was required to feed the craftsmen for the duration of their work and to sponsor a long and costly uyawe feast. ~

Natumuk, meaning "those who may hunger", traditionally have owned little land, and have been very poor. They have often been forced to borrow from he kadangyan at high interest rates and become indentured to them. The nawotwot, meaning nawatwat, the "disinherited" or "passed by," are the poorest of the poor. Most have traditionally worked as tenant farmers and servants to kandangyan. In the past, they were often slaves—generally children sold by impoverished families to lowlanders to pay off debts. If they were bought by fellow Ifugao, they were eventually freed, and their children were born free anyway. Government statistics on family income from 1988 showed that only 4 percent of Ifugao province’s population fell into the upper-income category while 75 percent belonged to the lower-income category.

Traditionally, kadangyan accumulating wealth primarily in rice lands and water buffalo (and in the past, slaves). Rice holdings had to be extensive enough to produce a surplus that could be loaned at high interest to namatuk families, effectively preventing borrowers from ever attaining kadangyan status themselves..Kadangyan competed with one another through the number and scale of ritual feasts they sponsored. While this status carried no formal political authority, the wealth it embodied translated into substantial social influence. Important community decisions depended on achieving consensus among all the kadangyan. Such consensus emerged only after these elites had engaged in public debate, allowing their personalities and rivalries to play out openly. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Ifugao Families and Property

A typical Ifugao household consists of a nuclear family. In the old days, once children were old enough to take care of themselves, they moved to the boys house or the girls house — same-sex dormitories called agamang. Traditionally, newlywed couples showed no preference living in the wife’s or husband’s community. The main goal was to establish a household near the largest concentration of inherited rice fields. Because incest taboos were extremely strict, brothers and sisters deliberately avoided close contact with siblings of the opposite sex. They took care to sleep separately, to be buried apart, and even to avoid sexual joking in one another’s presence. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

An individual’s kin group extended bilaterally to include great-great-grandparents and third cousins on both the maternal and paternal sides. In principle, marriage within this range was forbidden, although unions between second or third cousins could occur after the payment of fines in livestock and the performance of propitiatory sacrifices. The kin group bore collective responsibility for offenses committed by any of its members and was likewise obligated to seek vengeance or compensation for injuries done to its own. ~

Children could inherit property, as well as outstanding debts, from either parent. A widow or widower was permitted to remarry only after paying a gibu a fine imposed for engaging in sexual relations outside the original marriage, to the deceased spouse’s family. Both sexes may inherit property, with the firstborn getting te largest share. Illegitimate children receive support from the father but do not have inheritance rights.

Rice lands, forest lands, and valued heirlooms—such as jewelry, gongs, and Chinese jars—were held by individuals only in trust. Formally, such property belonged to a descent group whose members could trace lineage, through either parent, to a common ancestor. These holdings could be sold only under exceptional circumstances, such as to obtain water buffalo for sacrifices needed to cure serious illness or to sustain the dead in the afterlife. Even then, sale required the consent of relevant kin and the performance of an ibuy ceremony. ~

By contrast, houses, valuable trees, and crops of sweet potatoes were regarded as personal property and could be sold without an ibuy ritual. Untilled grasslands and forests far from settlements were open to anyone from the local area who cleared and cultivated them. Sweet potato swidden fields reverted to the public domain after being left fallow. ~

Ifugao Marriage and Sex

Monogamy is the norm among the Ifugao but some wealthy families practice polygyny. Incest prohibitions extend to first cousins. Marriage to more distant cousin can only be arranged after the payment of livestock penalties. Trial marriages between prospective couples are common. Courtship rituals take place at the girls houses. Wealthy families have traditionally arranged marriages through intermediaries. Families exchange gifts and maintain close ties after the marriage. Newlyweds often spend some time living with their parents before setting up housing of their own, often near a large rice field. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

Because marriage was regarded as a union of indefinite duration, a couple could agree to divorce at any time, though separation became rare after the birth of a first child. Divorces may occur after mutual consent or with the payment of damages if contested. Grounds for divorce include omens, no children, cruelty, desertion and change of affection. When a marriage ended without children, each partner retained the property inherited from his or her own kin. If children were involved, the property was assigned to them. In cases where the children were still minors, the parent who took custody—usually the mother—managed the property until the children married. ~

An adolescent boy was free to visit an adolescent girl in her agamang dormitory and engage in sexual relations with her, provided that the girl did not have more than one lover at a time. Most individuals went through several such “trial marriages” before entering into a permanent union. Wealthier families, using monbaga as intermediaries, took greater care to arrange marriages for their children with partners of comparable status and to settle inheritance matters in advance. Betrothal was marked by the exchange of pigs and other gifts, establishing a close alliance between the two families. The marriage bond was then formalized through a sequence of four wedding ceremonies involving pig and chicken sacrifices, communal feasting, divination by bile sac augury, and, in the final rite, the presentation of jars, cloth, and knives from the groom’s family to that of the bride. With each successive ceremony, the fines imposed for breaking off the marriage increased. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Ifugao Women and Gender

Ifugao men are responsible for building maintaining the terraces while women plant, weed and harvest the rice. Women use wooden pestles and stone mortars to pound rice into a shape dictated by ancient tradition. Women also spend many hours weaving fabrics that are unique to their village. Children are carried around by both men and women in scarves knotted around their bodies.

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “It is pertinent to remark that the Ifugaos treat their women well; for example, the men do the heavy work, and there are no women cargadores. In fact, the sexes seemed to me to be on terms of perfect equality. The people in general appeared to be cheerful, good-humored, and hospitable. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

In 2000, literacy rates in the Cordillera Administrative Region, which includes Ifugao Province, were slightly lower for women (90 percent) than for men (90.8 percent). Within Ifugao itself, males made up 55.5 percent of elementary school pupils despite constituting only 51 percent of the overall population. At educational levels beyond high school, however, women outnumbered men: they accounted for 55 percent of college and university students and 64 percent of academic degree holders. ~ [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Women’s roles in Ifugao society are not viewed as being confined to motherhood. Their labor is understood as complementary to that of men, as seen in rice cultivation, where men and women perform different but equally vital tasks. Even elite women who are financially secure commonly work outside the home, and elderly women continue farm labor not only from necessity but also from personal commitment and enjoyment. Industriousness is valued in women more highly than physical beauty. At the same time, women are regarded as the “weaker” sex, whose work is considered lighter than men’s and therefore deserving of lower pay. In the early 1990s, women’s agricultural wages were about half those of men and fell well below the legal minimum wage. Although women manage household finances, they often feel less free than their husbands to spend money on themselves, while men frequently use household funds for drinking or gambling—practices their wives openly criticize. ~

Traditional leadership roles are dominated by elite men. Men are believed to possess superior oratorical skills, which are seen as essential for leadership, and most senior government officials are male. Women do participate in local community councils but remain a minority. A woman’s status, however, is shaped by more than gender alone: a female kadangyan or an older woman may wield more influence than a younger man of lower social standing. The growing influence of Christianity has tended to reinforce women’s subordinate status in traditional culture, while the expansion of a cash-based economy—where men have greater access to wage labor and higher incomes outside the home—has further devalued the unpaid domestic and agricultural work performed by women.

Ifugao Life

In the 1990s older Ifugao around Batad continued to live as their ancestors did. Some men still wore loincloths; and the practice of headhunting was given up only a few decades earlier. In the late 1980s, I heard stories about a bus driver that hit and killed an Ifugao woman, whose relatives formed a head hunting party to seek revenge but were stopped before they could do anything. The Ifugao are fond of chewing betel nut. I asked a couple Ifugao men why they liked chewing it and they said it cleans their teeth, and then smiled with half their teeth missing.

Surveys in the 1980s counted 70,000 Ifugao but few of these were pure blooded and few retained their tradition customs. Most have forsaken their traditional loin clothes, spears and betel nut and moved to towns where money and jobs could be found. [Source: "Vanishing Tribes" by Alain Cheneviére, Doubleday & Co, Garden City, New York, 1987]

The average family income in the Cordillera Administrative Region, which includes Ifugao Province, was 192,000 pesos (US$3,765) in 2006. This was one of the highest averages in the country, compared to the national average of 173,000 pesos, the 311,000 pesos in the National Capital Region, the 198,000 pesos in Southern Tagalog, and the 143,000 and 142,000 pesos in the neighboring Cagayan Valley and Ilocos regions, respectively. However, in 2000, Ifugao province had the fourth lowest Human Development Index (HDI) in the country, at 0.351 (combining measures of health, education, and income), above provinces in the Sulu archipelago. The Philippines' national HDI was 0.656. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

According to the 2000 census, 35.2 percent of households in Ifugao province had access to a community faucet, 11.5 percent had their own faucet, and 8.2 percent had access to a shared deep well. Meanwhile, 17.4 percent obtained water from springs, lakes, rivers, or rain. Nearly half of the households (46.3 percent) disposed of their garbage by burning it, 30.2 percent by burying it in a pit, and 9.1 percent by feeding it to their animals. Only 6.5 percent had it picked up by a collection truck. Fifty-eight and a half percent of houses were lit with kerosene lamps, 36.8 percent with electricity, and 3.5 percent with firewood. Thirty-four percent of households lacked basic appliances of any kind. Meanwhile, 64 percent had a radio, 15.4 percent had a television, 10 percent had a refrigerator, 5.4 percent had a VCR, 1.5 percent had a telephone or cell phone, 17.4 percent had a washing machine, and 6.3 percent had a motorized vehicle.

By 2000, literacy in the Cordillera Administrative Region, which includes Ifugao Province, had reached 90.5 percent. Among Ifugao residents aged five and older, 46.2 percent had attended elementary school, 21.9 percent high school, and 8.9 percent college or university.

Ifugao Villages and Houses

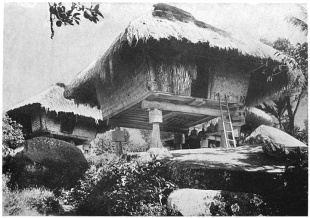

The Ifugao live in small settlements set up in the valleys and along the mountainsides. Hamlets (“buble”) typically have 8 to 12 dwellings, housing 30 or more people The houses are built on stilts close to the rice fields. There are also temporary buildings, such as houses for unmarried people, on the ground. Some villages are made up of extensive communities with hundreds of houses. Toward the northern edge of Ifugao territory, village houses are scattered over broad valley bottoms, separated by fields. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Each house consists of as single nine-foot-wide room. The roof is a thatch pyramid and the house itself is supported on four stilts, or piles, with cylindrical fenders to block climbing rats. The pyramid-shaped roof is used as a bedroom, kitchen and storeroom. All in one space! There are no windows. To please the gods, the skull of a sacrificed pig is fixed on the outside of the house. They are also granaries made of timber. The houses look like granaries but are larger and have a hearth.

Houses vary in size according to the wealth of the owner. They are well-built wooden structures made to last for generations. They have few furnishings or decorations, except for the occasional carved human figure on the doors and, formerly, a shelf for displaying the skulls of enemies and sacrificial animals. Larger communities have stone platforms at their centers where communal celebrations are held and prestigious houses are built. Less permanent structures, such as agamang dormitories for girls and unmarried women, are built on the ground. ~

To get inside the house it is necessary to climb a ladder which is pulled up at night, namely to keep rats out. The homes of rich people are adorned with skulls of sacrificed buffalos. The more buffalos a family can afford to sacrifice and in turn display the wealthier they are. Some upper class homes are decorated with paintings and geometric engravings. In the old days there were shelves with skulls of enemies killed in battle or head hunting raids. **

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “We walked about the village and examined one or two houses. These are all of one room, entered by a ladder drawn up at night, and set up on stout posts seven or eight feet high; the roof is thatched, and the walls, made of wattle (suali), flare out from the base determined by the tops of the posts. In cutting the posts down to suitable size (say 10 inches in diameter), a flange, or collar, is left near the top to keep rats out; chicken-coops hang around, and formerly human skulls, too, were set about. But the Ifugaos, thanks to Gallman, as already said, have abandoned head-hunting, and the skulls in hand, if kept at all, are now hidden inside their owner’s houses, their places being taken by carabao heads and horns.

One house had a tahibi, or rest-couch; only rich people can own these, cut out as they are of a single log, in longitudinal cross-section like an inverted and very flat V with suitable head- and foot-supports. The notable who wishes to own one of these luxurious couches gets his friends to cut down the tree (which [80] is necessarily of very large size), to haul the log, and to carve out the couch, feeding them the while. Considering the lack of tools, trails, and animals, the labor must be incredible and the cost enormous. However, wealth will have its way in Kiangan as well as in Paris. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912]

Ifugao Food

Agricultural produce supplies about 84 percent of the Ifugao diet. Rice and sweet potatoes are the staple foods, with rice accorded far greater prestige. Maize, grown on sweet-potato swidden fields and ground into meal, is also significant. The Ifugao eat a wide range of vegetables and fruits, including beans, radishes, cabbage, lettuce, peas, taro, yams, cowpeas, lima beans, okra, greengrams and other legumes, as well as jackfruit, grapefruit, citrus, coconut, and banana. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Roughly 10 percent of the diet consists of animal protein gathered from flooded rice fields—tilapia minnows, frogs, snails, and especially ginga, a type of freshwater clam. Meat is obtained from domesticated pigs, goats, chickens, and, on ritual occasions, water buffalo, as well as from wild animals such as deer, buffalo, pig, civet cat, wild cat, python, iguana, cobra, and bat; only monkeys are hunted solely for sport. Locusts, crickets, and ants are also eaten. ~

In the Hudhud epic, heroes are often portrayed as staggering figures, reflecting the high esteem placed on the rare ability to withstand heavy intoxication. Alcohol plays a central role in feasts and ritual life. Poorer households dilute rice wine (bayah) with water, while wealthy kadangyan mix bayah with sugarcane juice to produce bahi, the juice being extracted with a press. ~

Bender (1975) noted that "The Ifugao of the Philippines eat three species of dragon fly and locusts. These are boiled, dried, and powdered. They also relish red ants, water bugs, and beetles, as well as flying ants, which are usually fried in lard." Showalter (1929) furnishes a photograph of Ifugao women in Luzon preparing locusts by roasting them, and another showing an Ifugao locust catcher with his large net.[Source: www.food-insects.com]

Ifugao Killing of a Water Buffalo in 1912

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Since these highlanders have but little meat to eat, it is the policy of the Government, on the occasion of these annual progresses, to furnish a few carabaos [water buffalos], so that some of the people, at least, while they are the guests of the Government, may have what they are fondest of and most infrequently get. And they have been until recently allowed to slaughter the carabao, according to their own custom, in competition, catch-as-catch-can, so to say. For the poor beast, tethered and eating grass all unconscious of its fate, or else directly led out, is surrounded by a mob of men and boys, each with his bolo. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

At a signal given, the crowd rushes on the animal, and each man hacks and cuts at the part nearest to him, the rule of the game being that any part cut off must be carried out of the rush and deposited on the ground before it can become the bearer’s property. Accordingly, no sooner is a piece separated and brought out than it is pounced on by others who try to take it away; usually a division takes place, subject to further sub-division, however, if other claimants are at hand. The competition is not only tremendous, but dangerous, for in their excitement the contestants frequently wound one another. The Government (i.e., Mr. Worcester), while at first necessarily allowing this sort of butchering, has steadily discouraged and gradually reduced it, so that at Kiangan, for example, the people were told that this was the last time they would ever be allowed to kill beef in this fashion. It was pointed out to them that the purpose being to furnish meat, their method of killing was so uneconomical that the beef was really ruined, and nobody got what he was really entitled to.

“On this occasion, the carabao was tied to a stake in a small swale and I nerved myself to look on. I saw the first cuts, the poor beast look up from his grass in astonishment, totter, reel, and fall as blows rained on him from all sides. The crowd, closing in, mercifully hid the rest from view; the victim dying game without a sound. In this respect, as well as in many others, the carabao is a very different animal from the pig. But, while looking on at the mound of cutting, hacking, sweating, and struggling butchers, the smell of fresh blood over all, something occurred that completely shifted the center of interest....When I turned again to see how they were getting on, I found that they had disappeared, and, walking to the place, saw not a trace of the butchery save the trampled ground and a small heap of undigested grass. Mr. Worcester had told me before that I should find this to be the case; not a shred of hoof, hide, or bone had been left behind.

Ifugao Clothes

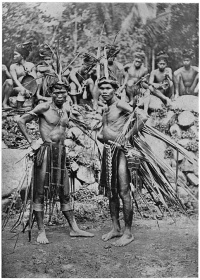

Ifugao and Ilocano women have traditionally worn short, tight-fitting, hand-woven skirts with colorful horizontal stripes, with a white short-sleeve blouse and a loose striped jackets. They have traditionally gone barefoot and sometimes tied a colored band around their head. Traditional male attire consists of a G-string, a loincloth that leaves the sides of the thighs exposed while hanging down in front. Some men still wear loincloths and go everywhere barefoot. They are quite sure-footed on mountain trails. Their toes and feet grip on to rocks like the hand of a pitcher grasping a baseball. In the past, women went bare-chested. Men who had not yet avenged the murder of their father allowed their hair to grow long, and tattooing was once widespread. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Members of the kadangyan (wealthy elite) signal their status through clothing and adornments reserved for their class. Elite men wear an ornate G-string, a tasseled hip bag, kidney-shaped gold earrings, and an elaborate headdress composed of a turban-like cloth, a hornbill skull, and water buffalo horns. Elite women wear finely made skirts, tasseled belts, gold earrings, four strands of bead necklaces, white and red bead strings to secure their long hair, and a small brass statuette.

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “ As elsewhere, but few clothes are seen: the women wear a short striped skirt sarong-wise, but bare the bosom. However, they are beginning to cover it, just as a few of them had regular umbrellas. They leave the navel uncovered; to conceal it would be immodest. The men are naked save the gee-string, unless a leglet of brass wire under the knee be regarded as a garment; the bodies of many of them are tattooed in a leaf-like pattern. A few men had the native blanket hanging from their shoulders, but leaving the body bare in front. The prevailing color is blue; at Campote it is red. The hair looked as though a bowl had been clapped on the head at an angle of forty-five degrees, and all projecting locks cut off.

If the hair is long, it means that the wearer has made a vow to let it grow until he has killed someone or burnt an enemy’s house. We saw such a long-haired man this day. Some of the men wore over their gee-strings belts made of shell (mother-of-pearl), with a long free end hanging down in front. These belts are very costly and highly thought of. Earrings are common, but apparently the lobe of the ear is not unduly distended. Here at Kiangan, the earring consists of a spiral of very fine brass wire. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Ifugao Work, Agriculture, and Hunting

Although modern education, administration, commerce, and tourism offer some Ifugao people nontraditional occupational opportunities, most remain farmers. Rice is of utmost importance to the Ifugao. It s thought their name comes form “ipugo”, meaning “rice eaters.” Bulo is the Ifugao rice god and a symbol of wealth. Many Ifugao used to keep a wooden image of the god in their houses to insure prosperity. Unfortunately many families have sold them to tourists. The Ifugao used to have festivals for the planting, growing and harvesting of rice. They have traditionally grown “tinawon” rice, which many say has a delightful aromatic taste that most Ifugao love. In recent years some have stop growing it in favor of more high yield varieties, [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

About 40 percent of the Ifugao diet comes from agriculture, most of it wetland rice. Ten percent is from fish, clams and snails living in the rice fields. Owning rice fields is the main indicator of status (even more so since the end of headhunting). When flooded, rice fields also provide animal protein in the form of small fish, frogs, etc. After the harvest, farmers grow taro. cotton, beans, radishes, cabbage, lettuce, and peas on the soggy rice stalks.

Additionally, the Ifugao cultivate sweet potatoes, a low-prestige staple, in swidden fields on hillsides. These fields also support a variety of vegetables, as well as sugarcane and tobacco. Tree crops complete the picture, including coffee, jackfruit, grapefruit, rattan, citrus, areca, coconuts, and bananas. The Ifugao raise pigs, goats, and chickens. They keep the chickens in baskets under their houses at night. They also import water buffalo from the lowlands to sacrifice to their ancestors, never using them as draft animals. Hunting and gathering wild plants only make a minor contribution to their subsistence. ~

Ifugao men hunt rodents, small mammals and wild pigs with spears, which come in three varieties: one which is used as a hunting stick, another with a magically-shaped iron tip reserved for big game, and yet another used for ceremonial dances, which never leaves the village. Hunters carry provisions of rice and sweet potato in backpacks fashioned from wild pig hide.**

Many men go down into the lowlands to trade. The main export is coffee, while imported goods include livestock, cotton, brass wire, cloth, beads, crude steel, and Chinese jars and gongs. The Ifugao trade knives, pots, spears, and salt among themselves. Market gardening is increasing in importance. In the city of Baguio, located 50 kilometers southwest of the Ifugao territory, lowlanders and tourists from as far away as Manila make a point of buying vegetables grown by the mountain peoples.

Banaue Rice Terraces

The Banaue area (six hours from Manila by bus) contains magnificent rice terraces that have been described as the eighth wonder of the world. Originally constructed by the Ifugao people, who still maintain them, the terraces rise from the steep river gorges and ascend—and sometimes engulf— the mountains like green amphitheaters. The rice terraces around Banaue were designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1995.

There is some evidence that the first rice terraces may have been carved out of the mountains as early as 1000 B.C. Most were built in the last four centuries. By some estimated the rice terraces would extend for 11,400 miles if placed from end to end. Among the Ifugao, a man’s status is based on his rice fields. Ownership of the paddies and terraces, and the responsibility for taking care is passed down from one generation to the next. The system, allows the Ifugao to live in fair dense concentrations.

Irrigation is achieved through a network of dikes and sluices. The size of the fields range from a few square meters to more than one hectare, with the average size being 270 square meters. In rocky terrain the terraces are built from the top down, by first hollowing out the top of a mountain and surrounding the outside with narrow platforms. Stones that are removed from the fields are used to construct the terrace walls, whose cracks are filled with chalk-base plaster. The platforms are then filled with earth. In this fashion the terraces are built down the mountain until the reach the valley.

If the soil is crumbly work begins at the bottom and moves upwards. Under these circumstances the terrace builders they try to dig out the earth to reach the rock which is used as a solid base and which, if necessary, can be supported with tree trunks. Unfortunately, the terraces are starting to erode and deteriorate somewhat because younger Ifugao are not taking care of them as their attention is distracted by other things like television, smart phones and making money.

See Separate Articles CORDILLERA RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON: HISTORY, CONSTRUCTION, ARCHAEOLOGY factsanddetails.com ; IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026