IFUGAO RICE TERRACES

For some 2,000 years the Ifugao’s highland rice fields have traced the natural contours of the mountains. They are the outcome of knowledge transmitted across generations and embody sacred traditions and a finely balanced social order, together creating a landscape of striking beauty that expresses harmony between people and nature. The terraces are found in the remote reaches of the Philippine Cordillera mountain range on northern Luzon. Although the historic terraces extend across a wide area, the property inscribed by UNESCO comprises five clusters representing the most intact and impressive examples, situated in four municipalities. All were created by the Ifugao ethnic group, a minority population that has inhabited these mountains for millennia. [Source: UNESCO]

The five inscribed clusters are: 1) the Nagacadan terrace cluster in the municipality of Kiangan, distinguished by two separate ascending rows of terraces divided by a river; 2) the Hungduan terrace cluster, which uniquely unfolds in a spider-web pattern; 3) the central Mayoyao terrace cluster, noted for terraces interwoven with traditional farmers’ bale (houses) and alang (granaries); 4) the Bangaan terrace cluster in the municipality of Banaue, which forms the backdrop to a classic Ifugao village; and 5) the Batad terrace cluster in the municipality of Banaue, set within amphitheater-like semicircular terraces with a village at their base. ^^^

The Ifugao Rice Terraces exemplify the complete integration of physical, socio-cultural, economic, religious, and political dimensions. They constitute a living cultural landscape of exceptional beauty. Built at higher elevations and on steeper slopes than most other terraced systems, the Ifugao terraces—formed from stone or mud walls carefully carved into hillsides—combined with intricate irrigation networks that capture water from mountain forests and a complex agricultural regime, demonstrate an engineering mastery still admired today.

Through ritual practices, chants, and symbols emphasizing ecological balance, the Ifugao community has preserved the integrity of the terraces’ traditional management system over centuries, ensuring the authenticity of both the original landscape engineering and wet-rice cultivation. When this balance is disrupted, the entire system begins to fail, but when all elements operate together the authenticity remains complete.

RELATED ARTICLES:

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, PINE FORESTS, BONTOC RICE TERRACES factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

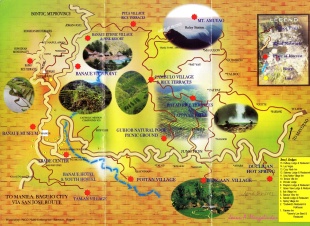

Ifugao Province

Ifugao Province (322 kilometers north of Manila) is where Banaue, Batad and many of the famous rice terraces are located. The province is a land-locked area located at the foot of the Cordillera Mountain Range, bounded on the west by the province of Benguet, Nueva Viscaya on the south, Isabela on the east, and on the north by Mountain Province.

Ifugao Province covers an area of 2,517.78 square kilometers and is home to only 200,000 people. It has a population density of 77 people per square kilometers, making it one of the most sparsely population areas of the Philippines. Politically, it is sub-divided into 11 municipalities and 178 barangays, with Lagawe serving as the provincial capital town.

The province has a a dry season from November to April and rainy season the rest of the year. The hottest months are March and April while the coolest months are November to February. English is widely spoken and understood among the populace. The local language is Ifugao. the Ilocano and Tagalog Farming, tourism, trading industry (gift, toys & house wares); services; manufacturing (garments & textiles); and food & beverages.

Banaue

Banaue itself is a pretty big town in the region. It has a lively market and can be reached by paved roads. There are lots of backpackers, guest houses and cheap restaurants. It is located in valley an elevation of 1,200 meters (3,960 feet).

Worth checking out in the town is the Museum of Cordilleran Sculpture, founded by George and Candida Ida Schenk in the 1980s. It grew out of a small antique store in Manilla and desire to preserve a dying craft. There are over 1,000 pieces in the museum’s collection, ranging from large carved wooden Bululs, masks to smaller scale figures, textiles, utilitarian objects, and composite objects

On the road to Bontoc, there is a lot of beautiful views of the rice terraces. Walking from Banaue up to the main view point takes one or two 2 hours, depending how often you stop to enjoy the superb view. Try to get as far away as possible from Banaue: the higher up you got the better the views. It is possible to walk through the rice terraces but is also easy to get lost, so best take a guide if that is what you want to do.

It is possible to take a bus directly from Manila to Banaue. Ohayami Trans (Lacson Ave cnr Fajardo St, Sampaloc, Manila, near University of Sto. Tomas or take the train from the Legarda Station & then a trickshaw to the terminal) and GV Florida Transport (Dangwa Transport Co., Lacson ave. cor. Earnshaw st. Sampaloc Manila, Sampaloc terminal) both operate daily buses from Manila that take 9-10 hours and cost about US$10. You can also reach Banaue from Baguio and Bontoc. Because of road conditions and the number of things to see, tourists often hire a car with a driver for the seven-to eight-hour trip, driving to Bontoc or Banaue but make several stops along the way.

Banaue Rice Terraces

Banaue (10 hours from Manila by bus) contains magnificent rice terraces that have been described as the eighth wonder of the world. Originally constructed between 1000 and 2000 years ago by the Ifugao people, who still maintain them, the terraces rise from the steep river gorges and ascend—and sometimes engulf— the mountains like green amphitheaters. It is said that if the terraces were laid end to end they would circumnavigate the earth.

The rice terraces around Banaue were designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1995. They : somewhat similar to the rice terraces in Bali, except bigger and more all encompassing. In some cases they extend all from the top of the mountains down to the rivers and streams below. The view an entire chain of mountains terraced to their highest peaks for the cultivation of rice is truly an amazing site

Banaue Rice Terraces are part of the rice terraces of the Philippines Cordilleras that were named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. There is some evidence that the first rice terraces may have been carved out of the mountains as early as 1000 B.C. Most were built in the last four centuries. By some estimated the rice terraces would extend for 11,400 miles if placed from end to end. Among the Ifugao, a man’s status is based on his rice fields. Ownership of the paddies and terraces, and the responsibility for taking care is passed down from one generation to the next. The system, allows the Ifugao to live in fairly dense concentrations in an otherwise inhospitable region.

Batad: in the Heart of the Banaue Area Rice Terraces

Batad (one hour jeepney ride and two hour walk from Banaue) is the home of some of the most spectacular rice terraces in the Banaue area. Here the mud and stone walled structures look like a tropical stairway to heaven that continue on and on, up one winding river gorge after another, and look the Bali rice terraces transplanted on the foothills of the Himalayas. They are especially beautiful in the morning sunlight when mist still clings to the mountains.

The terraces are laid like a an amphitheater. Each terrace is supported by stone walls that give the terraces a neat, organized look. The further away from the terraces you are the more their imperfection are hidden and the cleaner their lines look. When you look up the terraces they look like giant staircases. When you look down on them, when the paddies contain water, they resemble shimmering saucers of vegetation and liquid piled on one another.

Water is kept in the terraces year round.. If they dry out, the terrace walls crack, increasing the likelihood of a landslide in heavy rain. Irrigation water in the dry season comes from steams that tumble down out of the mountains. Some of the water is carried in bamboo pipes. Living in the paddies is a unique ecosystem that includes frogs, snakes, snails, fish and wading birds. In recent years some of the terraces have fallen into disrepair as an increasing number of Ifugao have abandoned traditional life and gone to the cities and plantations in search of work.

Batad lies at the center of center of a “living cultural landscape” designated by UNESCO. Numerous hiking trails wind along the edges of the terraces and the walls of the terraces themselves. Destinations include beautiful waterfalls, swimming holes, large mountain, villages, former guerilla camps and pine forests. Guides, often old Ifugao men, can be arranged in Batad, which is (or at least was) also a popular hangout with Israelis.

Ifugao Rice Terraces in Banaue in 1910

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Banaue stands at the head of a very deep valley, shut in by mountains on three sides; the stream sweeping the base of the plateau breaks through on the south. This plateau rises sharply from the floor of the valley; in fact, it is a tongue thrust out by the neighboring mountain, and forms a position of great natural strength against any enemy unprovided with firearms. Across the stream on the east mount the rice-terraces over a thousand feet above the level of the stream; a stupendous piece of work, surpassed at only one or two other places in Luzon.

Elsewhere we saw terraces higher up, but none on so great a scale, so completely enlacing the slope from base to crest. The retaining walls here are all of stone, brought up by hand from the stream below. This stream makes its way down to the Mayoyao country, and I was told that the entire valley, thirty-five or forty miles, was a continuity of terraces. Indeed, it requires some time and reflection to realize how splendid this piece of work is: it is almost overwhelming to think what these people have done to get their daily bread. In contemplation of their successful labors, one is justified in believing that, if given a chance, they will yet count, and that heavily, in the destinies of the Archipelago. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Banaue was first visited by Mr. Worcester in 1903, coming down from the north with a party of Igorots. At the head of the pass he was met by an armed deputation of Ifugaos, who came to inquire the purpose of his visit. Was it peace or was it war? He could have either! But he must decide, and immediately. Assured as to the nature of the visit, the head man then gave Mr. Worcester a white rooster, symbol of peace and amity, and escorted him in. But the accompanying Igorots came very near undoing all of Mr. Worcester’s plans.

Not only were they shut in during their stay, an obvious and necessary condition of good order and the preservation of peace, but, on Mr. Worcester’s asking food for them, they were told they could have camotes, but no rice; that rice was the food of men and warriors, and camotes that of women and children, and that the Igorots were not men. This almost upset the apple-cart, for the Igorots in a rage at once demanded to be released from their confinement so as to show these Ifugaos who were the real men. But counsels of peace prevailed. In fact, it is a matter of astonishment that Mr. Worcester should be alive to-day, so great at the outset was the danger of personal communication with the wild men of Luzon. It was not always a handsome white rooster, in token of peace, that was handed him; sometimes spears were thrown instead. However, on this trip of ours he got a whole poultry-yard of chickens, besides eggs in every stage of development from new-laid to that in which one could almost feel the pin-feathers sticking through the shell.

Rice Terrace Agriculture

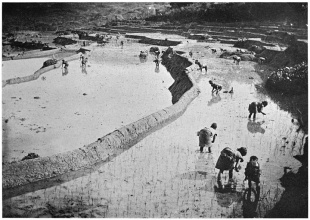

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: In the Banaue district, there are terrace walls certainly 75 feet in height, though many of these are not stoned, since the earth is of such a nature that it does not readily crumble...Turning the soil for the annual crop of irrigated rice begins in the middle of December and continues nearly two months. The labor of turning and fertilizing the soil and transplanting the young rice is all in progress at the same time—generally, too, in the same rice terrace. Before the soil is turned in a rice terrace it has given up its annual crop of camotes, and the water has been turned on to soften the earth. From two to twenty adults gather in a sementera, depending on the size of the field. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The rice terrace is about 20 by 50 feet, or about 1,000 square feet, and lies in the midst of the large valley area between Bontoc and Samoki. It is on the Samoki side of the river, but is the property of a Bontoc family. There are two groups of soil turners in the rice terrace—three men in one, and two unmarried women, an older married woman, and a youth in the other. At one end of the plat two, and part of the time three, women are transplanting rice. Four men are bringing fertilizer for the soil.

Let us watch the typical group of the three women and the youth: Each has a sharpened wooden turning stick, the kay-kay, a pole about 6 feet long and 2 inches in diameter. The four stand side by side with their kay-kay stuck in the earth, and, in unison, they take one step forward and push their tools from them, the earth under which the tools are thrust falling away and crumbling in the water before them. While it is falling away the toilers begin to sing, led by the elder woman. The purport of the most common soil-turning song is this: “It is hard work to turn the soil, but eating the rice is good.”

I saw only one variation from the above methods in the Bontoc area. In some of the large rice terraces in the flat river bottom near Bontoc village a herd of seventeen carabaos was skillfully milled round and round in the water, after the soil was turned, stirring and mixing the bed into a uniform ooze. The animals were managed by a man who drove them and turned them at will, using only his voice and a long switch. It is impossible to get carabaos to many irrigated rice terraces because of the high terrace walls, but this herd is used annually in the Bontoc river bottom.

Ifugao Rice Terrace People and Culture

During fiesta season in the rice terrace region, young men in vivid tribal dress beat out ancient rhythms on brass gongs as wild boars squeal before slaughter. The annual festivals, staged in isolated mountain villages after the rice planting that sustains daily life, play a crucial role in passing centuries-old traditions to a new generation. These customs are the spiritual core of the Cordillera ranges, where Ifugao communities continue to maintain the rice terraces. [Source: Karl Malakunas, AFP, May 31, 2015]

UNESCO has commends the Ifugao for living in harmony with nature over centuries—using herbs instead of pesticides, avoiding chemical fertilisers, and carefully managing scarce natural resources. Their irrigation system, which channels water from mountaintop forests and distributes it equitably across communities, is praised as a “mastery of engineering.”

As recently as a generation or two ago, many Ifugao villages and the lives of their residents closely mirrored those of centuries past. Today, large parts of the five listed districts—home to around 100,000 people — still retain many of the features celebrated by UNESCO. But profound change is taking hold.

Dressed in traditional attire at a recent festival, Mayoyao elder and rice farmer Mario Lachaona told Afp of the Ifugao aim of preserving customs while warning against idealising the past. “Life before was very hard,” said Lachaona, 68, a lean father of six and grandfather of 18. “Education was poor. There were no roads, so we walked long distances to buy food. We could not survive on rice alone.”

He said his grandchildren now enjoyed better nutrition and education, with far more opportunities beyond subsistence farming. “Life is much easier now,” Lachaona said. Plans to pave the only road into Mayoyao in the coming years are expected to make life easier still. Padchanan said the improved access would allow farmers to sell vegetables in distant towns, providing a valuable source of additional income.

Only a few hundred foreign tourists visit annually, and officials hope the paved road will attract many more. Molanida, however, fears such development may not be properly controlled.“It is up to the Ifugao people to decide whether they want to fight harder to conserve their culture and prevent chaotic development,” he said. “Otherwise, the rice terraces may become grass terraces.”

Banaue Rice Terrace Irrigation and Maintenance

The rice terraces of Banaue are still cultivated and maintained using traditional methods, even though many nearby terraces have been abandoned or have fallen temporarily out of use because of shifts in climate and rainfall patterns within the mountain watershed. In some villages, Christianization during the 1950s disrupted the performance of indigenous practices and rituals that were central to sustaining the human commitment needed to balance nature and society in the landscape; today, however, traditional rituals coexist alongside Christianity. Despite this continuity, the terraced landscape remains extremely fragile. The long-standing social balance that sustained the rice terraces for two thousand years is now seriously threatened by technological change and broader processes of social evolution. Rural-to-urban migration has reduced the agricultural labor force required to maintain the vast terrace system, while climate change has caused streams to dry up, and major earthquakes have altered water sources, shifted terrace dams, and forced the rerouting of irrigation systems. [Source: UNESCO]

Irrigation is managed through an interconnected system of dikes and sluices. Individual fields range in size from just a few square meters to more than one hectare, with an average area of about 270 square meters. In rocky areas, terraces are constructed from the top of the mountain downward by first carving out the summit and enclosing the outer edge with narrow platforms. Stones removed during excavation are reused to build terrace walls, with gaps sealed using a chalk-based plaster. The platforms are then filled with soil, and construction continues downward along the slope until the valley floor is reached.

Where the soil is loose or crumbly, construction instead begins at the bottom and proceeds upward. In such cases, terrace builders dig until they reach bedrock, which serves as a stable foundation and may be reinforced with tree trunks if necessary. Today, however, many terraces are beginning to erode and deteriorate. Younger Ifugao are less involved in their upkeep, as their attention is increasingly drawn to other pursuits such as television, smartphones, and opportunities to earn cash income.

For generations, the terraces have been safeguarded and regulated through ancestral land-use systems developed by the indigenous Ifugao community. Individual terraces are privately owned but protected through ancestral rights, customary laws, and traditional practices. The continued maintenance of the living rice terraces depends on strong communal cooperation rooted in detailed knowledge of the Ifugao agro-ecosystem’s biological diversity, a carefully calibrated annual cycle guided by lunar phases, zoning and land-use planning, extensive soil conservation measures, and mastery of an intricate pest-control system based on herbal preparations, all reinforced by religious rituals.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Philippines Tourism websites, Philippines government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in February 2026