MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION

Mountain Province is located on the eastern flank of the Cordillera Central. The area consists of mountains are partly eroded limestone basins drained by tributaries of the upper Abra and Chico river systems. The region is largely deforested and experiences a long rainy season lasting about nine months, with temperatures generally ranging from 4° to 32° C (40° to 90° F).

Mountain Province is known for it weaving and is the home of the Bontoc rice terraces and the Sagada hanging coffins. There are a a number of weaving centers sporting different designs that bespeak of the province’s cultural heritage. The people in this province practiced a traditional form of democratic governance led by the respected elders in the communityknown as Dap-ay/Ato that predates the Spanish.

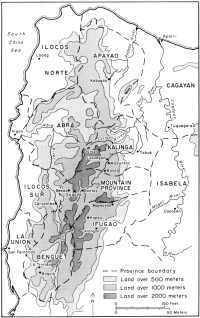

Mountain Province is bounded by Isabela on the east; the provinces of Kalinga, Apayao, and Abra on the north; the provinces of Benguet and Ifugao on the south; and the province of Ilocos Sur on the west. It has an area of 2,292.31 square kilometers, with 83 percent mountains and 17 percent hills and flat land. There are rivers, waterfalls and caves. The province has two seasons: dry from November to April and wet the rest of the year.

Mountain Province is composed of ten municipalities: Bontoc, Barlig, Bauko, Besao, Natonin, Paracelis, Sabangan, Sadanga, Sagada, and Tadian, with Bontoc as the capital town. There are 144 barangays comprising the 10 municipalities. The province is only home to about 160,000 people and has 72 people per square kilometer, making it one least densely populated provinces in the Philippines. Kankanaey is the major language-dialect spoken. English, Ilocano and Tagalog are also widely spoken.

Most people are farmers and there has been some effort to generate some small scale industry. The furniture industry, made from raw local materials such as pinewood and bamboo,. is a growing venture in the province. Bamboo and rattan basketry is also practiced. Backstrap weaving, an age-old handicraft, expanded to the use of loom. Colorful clothes are now used to make product like bags, purses, tapestry, ethnic costumes, blankets, linen, and fashion accessories.

RELATED ARTICLES:

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Northern Luzon and the Cordillera Central

Northern Luzon is noted for its colonial Spanish cities, tropical rain forest, faith healers, former-head-hunting Indian tribes, stunning rice terraces, and towering mountains. The Spanish influence in the Philippines is most noticeable in the mountainous northwestern Luzon provinces of Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur.

Luzon is roughly the size of Kentucky. Much of mountainous areas were left relatively untouched by the Spanish because they feared the headhunting tribes that lived there. The missionaries feared them to and as a result Christianity came late and mixed with local animist religions more than it displaced them. A number of rebellions were launched here against the Spanish. The New People’s Army has been active here in recent decades.

The Cordillera Central is the name of the rugged highlands in northern Luzon. It extends for about 320 kilometers and averages 65 kilometers in width. It is home to the highest mountains in the Philippines, some of which are over 2,470 meters high. It is also home to famous former headhunting tribes such as the Ifugao, Bontoc, Ilongot, Sagada Igorot, Kalingas, and Apayaos.

The southern Cordillera Central was explored by the Spanish because there were rumors of gold being found there but the northern reaches of the mountains were little explored by outsiders until the Americans arrived and even then there was not much contact until the 1970s when the Marcos regime proposed building four major dams in area on the Chico River. The local people were quite upset about the dams and the government had to send in troops to “pacify” the people. Many were killed and the dam projects were “permanently postponed.”

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “West of this Valley [the Cagayán] and separating it from the China Sea, stands a broad and complex system of mountains, known as the Caraballos Occidentales. Its length is nearly 200 miles, and its breadth, including the great spurs and subordinate ranges and ridges on either side, is fully one-third its length. The central range of the system forms the divide between the waters flowing to Cagayán River on the east and those flowing to the China Sea on the west. Its northern part bears the name Cordillera Norte. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Farther south it is called Cordillera Central, while the southern portion is called Cordillera Sur.” “At its south end the Cordillera Sur swings to the east, and, under the name of Caraballos Sur, joins the Sierra Madre, or East Coast Range.” This description, it must be understood, gives no adequate idea of the local intricacy of the system, while at the same time it is precisely this intricacy, both vertical and horizontal, that increases the cost and difficulty of making roads, and that has served in the past to keep the inhabitants of these regions apart.

Traveling to Bontoc Country in 1910

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “From Banawe we rode to Bontok, thirty-five miles, in one day. By midday we had crossed into Bontok sub-province and had reached a point on the trail above an Igorot village called Ambawan. Immediately on leaving Ambawan, we had to drop from the new trail (ours) to the old Spanish one for a short distance, for our trail had run plump upon a rock, waiting before removal for a little money to buy dynamite with. Having turned the rock, the climb back to the new trail proved to be quite a serious affair, as such things go, the path being so steep and so filled with loose sand and gravel clattering down the slope at each step that only one man leading his horse was allowed on it at a time, the next man not starting till his predecessor was well clear at the top. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

A loss of footing meant a tumble to the bottom, a matter of concern if we had all been on the path together. But finally we all got up and moved on, this time over the narrowest trail yet seen, a good part of the way not more than eighteen or twenty inches wide, with a smooth, bare slope of sixty to eighty degrees on the drop side, and the bottom of the valley one thousand to fifteen hundred feet or more below us. Many of us dismounted and walked, leading our horses for miles. With us went an Igorot guide or policeman, who carried a spear in one hand, and, although naked, held an umbrella over his head with the other, and a civilized umbrella too, no native thing. However, it must be admitted that it was raining.

“The mists prevented any general view of the country; as a matter of fact, we were at such an elevation as to be riding in the clouds, which had come down by reason of the rain. However, the valleys below us were occasionally in plain enough sight, showing some cultivation here and there, rice and camotes, the latter occasionally in queer spiral beds. The bird-scarers, too, were ingenious: a board hung by a cord from another cord stretched between two long and highly flexible bamboos on opposite banks of a stream, would be carried down by the current until the tension of its cord became greater than the thrust of the stream, when it would fly back and thus cause the bamboo poles to shake. This motion was repeated without end, and communicated by other cords suitably attached to other bamboo poles set here and there in the adjacent rice-paddy. From these hung rough representations of birds, and a system was thus provided in a state of continious agitation over the area, frequently of many acres, to be protected. The idea is simple and efficacious.

“This long stretch terminated in a land-slide leading down into the dry, rocky bed of a mountain stream. At the head of the slide we turned our mounts loose, and all got down as best we could, except Mr. Forbes, who rode down in state on his cow-pony. Once over, we crossed a village along the edge of a rice-terrace, in which our horses sank almost up to their knees. As the wall was fully fifteen feet high, a fall here into the paddy below would have been most serious; it would have been almost impossible to get one’s horse out. However, all things come to an end; we crossed the stream below by a bridge, one at a time (for the bridge was uncertain), and found ourselves in Talubin, where we were warmly greeted by Bishop Carroll of Vigan and [128] some of his priests. The Bishop, who was making the rounds of his diocese, had only a few days before fallen off the very trail we had just come over, and rolled down, pony and all, nearly two hundred feet, a lucky bush catching him before he had gone the remaining fourteen hundred or fifteen hundred.

“Talubin somehow bears a poor reputation; its inhabitants have a villainous look, owing, no doubt, in part to their being as black and dirty as coal-heavers. This in turn is due to the habit of sleeping in closed huts without a single exit for the smoke of the fire these people invariably make at night, their cook-fire probably, for they cook in their huts. However this may be, the people of this ranchería showed neither pleasure nor curiosity on seeing us, and I noticed that a Constabulary guard was present, patrolling up and down, as it were, with bayonets fixed and never taking their eyes off the natives that appeared. These Igorots lacked the cheerfulness and openness of our recent friends, the Ifugaos. Their houses were not so good, built on the ground itself, and soot-black inside. The whole village was dirty and gloomy and depressing, and yet it stands on the bank of a clean, cheerful stream. However, the inevitable gansas were here, but silent; one of them tied by its string to a human jaw-bone as a handle.

“This, it seems, is the fashionable and correct way to carry a gansa. At Talubin the sun came out, and so did some bottles of excellent red wine which the Bishop and his priests were kind enough to give us. But we did not tarry long, for Bontok was still some miles away. So we said good-bye to the Bishop and his staff and continued on our way. The country changed its aspect on leaving Talubin: the hills are lower and more rounded, and many pines appeared. The trail was decidedly better, but turned and twisted right and left, up and down. The country began to take on an air of civilization—why not? We were nearing the provincial capital; some paddies and fields were even fenced. At last, it being now nearly five of the afternoon, we struck a longish descent; at its foot was a broad stream, on the other side of which we could see Bontok, with apparently the whole of its population gathered on the bank to receive us. And so it was: the grown-ups farther back, with marshalled throngs of children on the margin itself. As we drew near, these began to sing; while fording, the strains sounded familiar, and for cause: as we emerged, the “Star-Spangled Banner” burst full upon us, the shock being somewhat tempered by the gansas we could hear a little ahead. We rode past, got in, and went to our several quarters, Gallman and I to Governor Evans’s cool and comfortable bungalow.”

Bontoc

Bontoc (three hours from Banaue) is the home of Bontoc and other Igorot tribes. Like the Ifugao, they are terrace builders and former headhunters. Even if you have seen the Banaue and Bataad terraces it is worth taking a look at the ones in Bontoc. The terrace walls of some are constructed of stone and have a different look. Many people who have visited them say they are more impressive than the ones at Bataad. There are reportedly even more impressive-looking terraces deeper in the mountains.

Bontoc town is relatively small and is very easy just to walk around the main street and find everything you need. Tricycles here are cheap if you need to go anywhere. There are few guest houses but it isn’t nearly as developed as Banaue. Among the places worth checking out are Mainit Hot Springs and Pusong and Ganga Cave Trek. The Bontoc Museum has some interesting photographs and artifacts of the Igorot

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Bontok is a place of importance, as becomes the capital of the Mountain Province. Here are schools, both secular and religious; two churches in building (1910), one of stone (Protestant Episcopal), the other of brick (Roman Catholic), each with its priest in residence; a Constabulary headquarters; a brick-kiln, worked by Bontoks; a two-storied brick house, serving temporarily as Government House, club and assembly; a fine provincial Government House in building; streets laid off and some built up, these in the civilized town. This list is not to be smiled at; a beginning has been made, a good strong beginning, full of hope, if the unseen elements established and forces developed are given a fair chance. The place was important before we came in; the native part is ancient and has a municipal organization of some interest. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Spain first occupied the place in 1855 and garrisoned it with several hundred Hokanos and Tagalogs. She has left behind a bad name; but the insurrectos (Aguinaldo’s people), who drove the Spaniards out, have left a worse. Both took without paying, both robbed and killed; the insurrectos added lying. Some four hundred Igorot warriors were persuaded by the insurrectos to join in resisting the Americans and went as far south as Caloocan just north of Manila, where, armed only with spears, axes, and shields, they took their place in line of battle, only to run when fire was opened. According to their own story, which they relate with a good deal of humor, they never stopped until they reached their native heath, feeling that the insurrectos had played a trick on them. Accordingly, it is not surprising that when March went through Bontok after Aguinaldo, the Igorot should have befriended him, nor later that the way should have been easy for us when we came in to stay, about seven or eight years ago.

“The site is attractive, a circular dish-shaped valley, about a mile and a half in diameter, bisected by the Rio Chico de Cagayán, with mountains forming a scarp all around. Bontok stands on the left bank, and Samoki on the right; separated only by a river easily fordable in the dry season, these two Igorot centers manage to live in tolerable peace with each other, but both have been steadily hostile to Talubin, only two hours away. However, it can not be too often said that this sort of hostility is diminishing, and perceptibly.

Maligcong Rice Terraces

Nearby Maligcong is known for its impressive rice terraces. To get the best view of these, one has to hike up Mt. Kopapey. It takes about 30 minutes of hike from the village to the mountain top. Many hikers try to climb early in the morning so they can get of the sea of clouds breaking up over the terraces. The view of the gently cascading hills engulfed by rice terraces is breathtaking. Mt. Kopapey feeds creeks and springs which supply water to Maligcong Rice Terraces. These creeks join together into a stream that flows the three-level Lipnok Falls.

The jeepneys to Maligcong leave from in front of Pines Kitchenette and Inn at 8:00am, 12:00noon 2:30pm, 4:30pm, 5:30pm to Maligcong and 6:30am, 8:00am, 9:00am, 2:00pm and 4:00pm to Bontoc, but may leave a little earlier if full. The price is low and it takes about half an hour to get there. There is a small entrance fee. The terraces start at the jeepney final stop. They are easier to explore than Batad and there are less steps to climb and there is a concrete path to the village. It takes a few hours to check them out. You can walk back to Bontoc in about 1½ hours.

Getting There From Manila:: Cabletours, departs 8:30 pm. The bus terminal is inside the Trinity University of Asia Campus at E. Rodriguez Ave. Cubao, Quezon City, 600 Pesos From Banaue: Jeepneys depart from the market, 1 hour 45 minutes. Scenic ride over the mountains with spectacular views. Site on the roof if you dare. From Baguio: GL Lizardo Trans departs 8:00am, 10:00am & 2:30pm from Governor pck Rd. Baguio City, 220 Pesos D'Rising Sun Buses departs 5:00am-1:00pm from Slaughter House Compound, Baguio City.

Building the Bontoc Area Rice Terraces

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The irrigated rice terraces are built with much care and labor. The earth is first cleared; the soil is carefully removed and placed in a pile; the rocks are dug out; the ground shaped, being excavated and filled until a level results. This task for a man whose only tools are sticks is no slight one. A huge boulder in the ground means hours—often days—of patient, animal-like digging and prying with hands and sticks before it is finally dislodged. When the ground is leveled the soil is put back over the plat, and very often is supplemented with other rich soil. These irrigated rice terraces are built along water courses or in such places as can be reached by turning running water to them. Inasmuch as the water must flow from one to another, there are practically no two rice terraces on the same level which are irrigated from the same water course. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The result is that every plat is upheld on its lower side, and usually on one or both ends, by a terrace wall. Much of the mountain land is well supplied with boulders and there is an endless water-worn supply in the beds of all streams. All terrace walls are built of these undressed stones piled together without cement or earth. These walls are called “faning.” They are from 1 to 20 and 30 feet high and from a foot to 18 inches wide at the top. The upper surface of the top layer of stones is quite flat and becomes the path among the rice terraces. The toiler ascends and descends among the terraces on stone steps made by single rocks projecting from the outside of the wall at regular intervals and at an angle easy of ascent and descent (see Pl. LIII).

These stone walls are usually weeded perfectly clean at least once each year, generally at the time the rice terrace is prepared for transplanting. This work falls to the women, who commonly perform it entirely nude. At times a scanty front-and-back apron of leaves is worn tucked under the girdle. Rocks built into dams and dikes are carried directly on the bare shoulders. Earth, carried to or from the building fields, in the trails, or about the dwellings, is put first in the tak-o-chûg, the basket-work scoop, holding about 30 or 40 pounds of earth, and this is carried by wooden handles lashed to both sides and is dumped into a transportation basket, called “ko-chuk-kod.” This is invariably hoisted to the shoulder when ready for transportation. When men carry water the fanga or olla is placed directly on the shoulder as are the rocks.

A single area consisting of several thousand acres of mountain side is frequently devoted to rice terraces, and I have yet to behold a more beautiful view of cultivated land than such an area of Igorot rice terraces. Winding in and out, following every projection, dipping into every pocket of the mountain, the walls ramble along like running things alive. Like giant stairways the terraces lead up and down the mountain side, and, whether the levels are empty, dirt-colored areas, fresh, green-carpeted stairs, or patches of ripening, yellow grain, the beholder is struck with the beauty of the artificial landscape and marvels at the industry of an otherwise savage people.

Irrigation of the Bontoc Rice Terraces

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: It is safe to say that nine-tenths of the available water supply of the dry season in the Bontoc area is utilized for irrigation. In some areas, as about Bontoc village, there is practically not a gallon of unused water where there is space for a rice terrace....The Igorot employ three methods of irrigation: One, the simplest and most natural, is to build rice terraces along a small stream which is turned into the upper rice terrace and passes from one to another, falling from terrace to terrace until all water is absorbed, evaporated, or all available or desired land is irrigated. Usually such streams are diverted from their courses, and they are often carried long distances out of their natural way. The second method is to divert a part of a river by means of a stone dam. The third method is still more artificial than the preceding—the water is lifted by direct human power from below the rice terrace and poured to run over the surface. The latter is not used much by the Bontoc.[Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The first method is the most common, since the mountains in Igorot land are full of small, usually perpetual, streams. There are practically no streams within reach of suitable village sites which are not exhausted by the Igorot agriculturist. Everywhere small streams are carefully guarded and turned wherever there is a square yard of earth that may be made into a rice rice terrace. Small streams in some cases have been wound for miles around the sides of a mountain, passing deep gullies and rivers in wooden troughs or tubes.

Much land along the river valleys is irrigated by means of dams, called by the Igorot “lung-ud.” During the season of 1903 there was one dam across the entire river at Bontoc, throwing all the water which did not leak through the stones into a large canal on the Bontoc side of the valley. Half a mile above this was another dam diverting one-half the stream to the same valley, only onto higher ground. Immediately below the main dam were two low piles of stones (designated weirs) jutting into the shallow stream from the Bontoc side, and each gathering sufficient water for a few rice terraces. Within a quarter of a mile below the main dam were three other loose, open weirs of rocks, two of which began on a shallow island, throwing water to the Samoki side of the river. In the stream a short distance farther down a shallow row of rocks and gravel turned water into three new rice terraces constructed early in the year on a gravel island in the river.

The main dam is about 12 feet high, 2 feet broad at the top, 8 or 10 at the bottom, and is about 300 feet long. It is built each year during November and December, and requires the labor of fifteen or twenty men for about six weeks. It is constructed of river-worn bowlders piled together without adhesive. The top stones are flat on the upper surface, and the dam is a pathway across the river for the people from the time of its completion until its destruction by the freshets of June or July.

The upper dam is a new piece of primitive engineering. It, with its canal, has been in mind for at least two years; but it was completed only in 1903. The dam is small, extending only half way across the river, and beginning on an island. This dam turns water into a canal averaging 3 feet wide and carrying about 5 inches of water. The canal, called “alak,” is about 3,000 feet long from the dam to the place of discharge into the level area. For about 530 feet of this distance it was impossible for the primitive engineer to construct a canal in the earth, as the solid rock of the mountain dips vertically into the river. About fifty sections of large pine trees were brought and hollowed into troughs, called “ta-lakan,” which have been secured above the water by means of buttresses, by wooden scaffolding, called “to-kod,” and by attachment to the overhanging rocks, until there is now a continuous artificial waterway from the dam to the tract of irrigated land.

Considerable engineering sense has been shown and no small amount of labor expended in the construction of this last irrigating scheme. The pine logs are a foot or more in diameter, and have a waterway dug in them about 10 or 12 inches deep and wide. These trees were felled and the troughs dug with the wasay, a short-handled tool with an iron blade only an inch or an inch and a half wide, and convertible alike into ax and adz.

Protecting Rice Terrace Rice from Birds, Rats and Monkeys

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The rice begins to fruit early in April, at which time systematic effort to protect the new grain from birds, rats, monkeys, and wild hogs commences. This effort continues until the harvest is completed, practically for three months. Much of this labor is performed by water power, much by wind power, and about all the children and old people in a village are busied from early dawn until twilight in the fields as independent guards. Besides, throughout the long night men and women build fires among the fields and guard their crop from the wild hog. It is a critical time with the Igorot. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The most natural, simplest, and undoubtedly the most successful protection of the grain is the presence of a person on the terrace walls of the fields, whether by day or night. Hundreds of fields are so guarded each day in Bontoc by old people and children, who frequently erect small screens of tall grass to shade and protect themselves from the sun. The next simplest method is one followed by the boys. They employ a hollow section of carabao horn, cut off at both ends and about 8 inches in length; it is called “kong-ok.” This the boys beat when birds are near, producing an open, resonant sound which may readily be heard a mile.

The wind tosses about over the growing grain various “scarecrows.” The pa-chek is one of these. It consists of a single large dry leaf, or a bunch of small dry leaves, suspended by a cord from a heavy, coarse grass 6 or 8 feet high; the leaf, the sa-gi-kak, hangs 4 feet above the fruit heads. It swings about slightly in the breeze, and probably is some protection against the birds. I believe it the least effective of the various things devised by the Igorot to protect his rice from the multitudes of ti-li(n?—the small, brown ricebird3 found broadly over the Archipelago.

The most picturesque of these wind-tossed bird scarers is the kilao. The kilao is a basket-work figure swung from a pole and is usually the shape and size of the distended wings of a large gull, though it is also made in other shapes, as that of man, the lizard, etc. The pole is about 20 feet high, and is stuck in the earth at such an angle that the swinging figure attached by a line at the top of the pole hangs well over the fields and about 3 or 4 feet above the grain (see Pl. LXVII). The bird-like kilao is hung by its middle, at what would be the neck of the bird, and it soars back and forth, up and down, in a remarkably lifelike way. There are often a dozen kilao in a space 4 rods square, and they are certainly effectual, if they look as bird-like to ti-li(n? as they do to man. When seen a short distance away they appear exactly like a flock of restless gulls turning and dipping in some harbor.

The water-power bird scarers are ingenious. Across a shallow, running rapids in the river or canal a line, called “pi-chug,” is stretched, fastened at one end to a yielding pole, and at the other to a rigid pole. A bowed piece of wood about 15 inches long and 3 inches wide, called “pit-ug,” is suspended by a line at each end from the horizontal cord. This pit-ug? is suspended in the rapids, by which it is carried quickly downstream as far as the elasticity of the yielding pole and the pi-chug? will allow, then it snaps suddenly back upstream and is ready to be carried down and repeat the jerk on the relaxing pole.

A system of cords passes high in the air from the jerking pole at the stream to other slender, jerked poles among the fields. From these poles a low jerking line runs over the fields, over which are stretched at right angles parallel cords within a few feet of the fruit heads. These parallel cords are also jerked, and their movement, together with that of the leaves depending from them, is sufficient to keep the birds away. One such machine may send its shock a quarter of a mile and trouble the birds over an area half an acre in extent.

There are many rodents, rats and mice, which destroy the growing grain during the night unless great care is taken to cheek them. The Igorot makes a small dead fall which he places in the path surrounding the fields. I have seen as many as five of these traps on a single side of a fields not more than 30 feet square. The trap has a closely woven, wooden dead fall, about 10 or 15 inches square; one end is set on the path and the other is supported in the air above it by a string. One end of this string is fastened to a tall stick planted in the earth, the lower end is tied to a short stick—a part of the “spring” held rigid beneath the dead fall until the trigger is touched. The dead fall drops when the rat, in touching the trigger, releases the lower end of the cord. The animal springs the trigger either by nibbling a bait on it or by running against it, and is immediately killed, since the dead fall is weighted with stones.

Fields near some forested mountains in the Bontoc area are pestered with monkeys. Day and night people remain on guard against them in lonely, dangerous places—just the kind of spot the head-hunter chooses wherein to surprise his enemy.

Transplanting and Harvesting Rice Terrace Rice in Bontoc

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: Transplanting is always the work of women, since they are recognized as quicker and more dexterous in most work with the hands than are the men. The women pull up the young rice plants in the seed beds and tie them in bunches about 4 inches in diameter. They transport them by basket to the newly prepared fields and dump them in the water so they will remain fresh. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Rice harvesting in Bontoc is a delightful and picturesque sight. Sa-fosab is the name of the rice harvesting ceremony. It is performed in a pathway adjoining each fields before a single grain is gathered. In the path the owner of the field builds a tiny fire beside which he stands while the harvesters sit in silence. The owner says: “So-mi-ka-ka pa-kü ta-mo i-sami sika k(n-po-num nan a-lang,” which, freely rendered, means, “Palay, when we carry you to the granary, increase greatly so that you will fill it.”

As soon as the ceremonial is said the speaker harvests one handful of the grain, after which the laborers arise and begin the harvest. In the trails leading past the fields two tall stalks of runo are planted, and these, called “pud-i-pud,” warn all Igorot that they must not pass the fields during the hours of the harvest. Nor will they ignore the warning, since if they do they are liable to forfeit a hog or other valuable possession to the owner of the grain.

Several harvesters, from four to a dozen, labor together in each fields. They begin at one side and pass across the plat, gathering all grain as they pass. Men and women work together, but women are recognized the better harvesters, since their hands are more nimble. Each fruited stalk is grasped shortly below the fruit head, and the upper section or joint of the stalk, together with the fruit head and topmost leaf, is pulled off.

As most Bontoc Igorot are right-handed, the plucked grain is laid in the left hand, the fruit heads projecting beyond between the thumb and forefinger while the leaf attached to each fruit head lies outside and below the thumb. When the proper amount of grain is in hand (a bunch of stalks about an inch in diameter) the useless leaves, all arranged for one grasp of the right hand, are stripped off and dropped; the bunch of fruit heads, topping a 6-inch section of clean stalk or straw is handed to a person who may be called the binder. This person in all harvests I have seen was a woman. She binds all the grain three, four, or five persons can pluck; and when there is one binder for every three gatherers the binder finds some time also to gather.

The binder passes a small, prepared strip of bamboo twice around the palay stalks, holds one end between her teeth and draws the binding tight; then she twists the two ends together, and the bunch is secure. The bunch, the manojo of the Spaniard, the si(n fi(ng-e? of the Igorot, is then piled up on the binder’s head until a load is made. Before each bunch is placed on the pile the fruitheads are spread out like an open fan. These piles are never completed until they are higher than the woman’s arm can reach—several of the last bunches being tossed in place, guided only by the tips of the fingers touching the butt of the straw. The women with their heads loaded high with ripened grain are striking figures—and one wonders at the security of the loads.

When a load is made it is borne to the transportation baskets in some part of the harvested section of the fields, where it is gently slid to the earth over the front of the head as the woman stoops forward. It is loaded into the basket at once unless there is a scarcity of binders in the field, in which case it awaits the completion of the harvest.

Pine Forests of the Cordillera Central

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “We set out next morning at five-thirty. Our journey so far, that is, since we mounted, had taken us over a preliminary range, and now we began a more serious climb. Far ahead and above us on the skyline, we could see a cut in the forest where our trail crossed the divide. But that was miles away, and in the meantime we were ascending a lovely valley, pines, grass, and bright red soil. It was delicious that morning, riding under the pines. And part of the pleasure was due to the fact that we had an unobstructed view in all directions, usually not the case in the tropical forest. At one point we had a full view of Arayat, at another of Santo Tomás, near which we had passed yesterday on coming down from Baguío. The valley was steep-walled, narrow and twisting, at one point closed by a single enormous rock nearly three hundred feet high—in fact, a conical hill rising right out of the floor of the valley, and apparently leaving just room for the stream to pass on one side. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“A curious fact was that while the mountains were decidedly northern-looking as to flora, yet the groins, wherever possible, were thoroughly tropical. For in these water runs off but slowly, with consequent richness of vegetation. And yet, on the other side of the divide which we were now approaching not a pine could be seen, but, on the contrary, the typical tropical forest in full development. The watershed, our skyline, was an almost absolute dividing-mark. At any rate, there the pines stopped short.

At the divide we crossed from Pangasinán into Nueva Vizcaya. And with the crossing began the forest just mentioned, and a long descent for us. Our immediate destination was Amugan, our first rest halt. It is of absolutely no use to try to describe this part of the trip. If the confusion of trees, vines, orchids, tree ferns, foliage plants, creepers, was bewildering, so was the impression produced. But we saw many examples of the most beautiful begonia in existence, in full blossom, gorgeous spheres of dark scarlet hanging above and around us. According to Mr. Worcester, all attempts to transplant it have failed. Its blossoms would be sometimes twenty and thirty feet in the air. Nothing could exceed the glory of these masses of flowers, sometimes a foot and more in diameter, as projected by the rays of the early morning sun against the dark green background, the whole glistening and dripping in the rain-like dew. Tree ferns abounded; we passed one that must have been over sixty feet high. At one halt the ground about was aflame with yellow orchids, growing out of the ground. And there was one plant that I recognized myself, unaided, the wild tomato, a little thing of eight or nine inches, but holding up its head with all the rest of them.

As always, on this trip, however, it was the splendor of the country that held the attention, the wild incoherent mountain masses thrown together apparently without order or system, buttressed peaks, mighty flanks riven to the core by deep valleys, radiating spurs, re-entrant gorges, the limit of vision filled by crenellated ranges in all the serenity of their distant majesty. And then, as our trail wound in and out, different aspects of the same elements would present themselves, until really the faculty of admiration became exhausted. And so on down we went, to be greeted as we neared Amugan by a sound of tom-toms; it was a party that had come out to welcome us, carrying the American flag and beating the gansa (tom-tom) by way of music. The gansa, made of bronze, in shape resembles a circular pan about twelve or thirteen inches in diameter, with a border of about two inches turned up at right angles to the face. On the march it is hung from a string and beaten with a stick. At a halt it is beaten with the open hand.

“After crossing a coffee plantation, we reached a little settlement, where we off-saddled and took a bite after six hours’ riding. The half-dozen houses of this tiny village are of the usual Filipino type, and the very few inhabitants were dressed after the fashion of the Christianized provinces. Nevertheless, we here first encountered the savage we had come up to see; for not only did they have the gansa, but they offered us a cañao. This is a feast of which we shall have splendid examples later on, with dancing, beating of gansas, drinking and so on, and the sacrifice of a pig.

“Here the affair was to be much smaller, all the elements being absent except the pig and drums. We had noticed as we dismounted a pig tied to a post and evidently in a very uneasy frame of mind, and justly, for, although the honor of a cañao was declined, on account of the length of the ceremony and of the distance we had yet to go, still they were resolved upon the death of the pig. He, however, at the same time had made up his mind to escape, and by a mighty effort broke his tether, and got off; but in vain, for after a short but exciting chase he was caught and then, an incision having been made in his belly, a sharpened stick was inserted and stirred about until his insides were thoroughly mixed, when he died.”

Mt. Pulag

Mt. Pulag is the second highest mountains in the Philippines at 2,922 meters high. Located in central Luzon, it is a natural habitat of endemic species of wild plants, such as dwarf bamboo and the benguet pine, and wild species of birds, long haired fruit bats, Philippine deer and giant bushy tailed cloud rats. Mt. Pulag was nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2006. Mt. Pulag National Park lies on the north and south spine of the Grand Cordillera Central that stretches from Pasaleng, Ilocos Norte to the Cordillera Provinces. It falls within the administrative jurisdiction of two Regions — Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) and Cagayan Valley State — and is located in provinces of Benguet, Ifugao, and Nueva Vizcaya.

According to UNESCO: “The whole park is located within the Philippine Cordillera Mountain Range and is very rugged, characterized by steep to very steep slopes at the mountainsides and generally rolling areas at the mountain peak. Mt. Pulag National Park is the highest peak in Luzon and is the second highest mountain in the Philippines with an elevation of 2,922 m. above sea level. The summit of Mt. Pulag is covered with grass and dwarf bamboo plants. At lower elevations, the mountainside has a mossy forest veiled with fog, and full of ferns, lichens and moss. Below this is the pine forest growing on barren, rocky slopes. Falls, rivers and small lakes mark the area. [Source: UNESCO]

“The Park has a large diversity of flora and fauna, many of which are endemic to the mountain. Its wildlife includes threatened mammals such as the Philippine Brown Deer, Northern Luzon Giant Cloud Rat and the Luzon Pygmy Fruit Bat. One can also find several orchid species some of which are possibly endemic to Mt. Pulag, and other rare flora such as the pitcher plant.

“Mt. Pulag is an important watershed providing the water necessities of many stakeholders for domestic and industrial use, irrigation, hydroelectric power production and aquaculture. Mt. Pulag was proclaimed National Park by virtue of Pres. Proclamation No. 75 on February 20, 1987 covering an area of 11,550 hectares. It was established to protect and preserve the natural features of the area such as its outstanding vegetation and wildlife. It belongs to the Cordillera Biogeographic Zone located in Northern Luzon. Mt. Pulag is a National Integrated Protected Areas Programme (NIPAP) site”

On climbing Mt. Pulag, 59-year-old Boboy Yonzon wrote: “Mt. Pulag was truly challenging, especially on the last ascent to the peak, which began at 4 a.m., in time for sunrise. The freezing temperature and thin air almost made me black out, but I was a stubborn bull....After much huffing and puffing, I finally made it to the summit just as cries of triumph greeted the sun. Its rays broke through the thick clouds and blanketed the narrow mountaintop with golden yellow.”

Getting there: Several buses travel from Manila to Baguio. From Baguio, you can rent a jeep with a driver to take you to Babadak Ranger Station, the jump-off point to Mt. Pulag. There are four routes from Babadak to Mt. Pulag, and the easiest is the Ambangeg route. To schedule a trip, you must reserve a slot through Park Superintendent Emerita Albas at mobile no. (+63) 919 6315402. She’s in charge of assigning your guides and porters for the climb.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Philippines Tourism websites, Philippines government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in February 2026