BONTOC HEAD HUNTING

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in 1912: The practice of head-hunting still exists in the Bontok country, though the steady discouragement of the Government is beginning to tell. Here in Bontok itself, a boy, employed as a servant in the Constabulary mess, dared not leave the mess quarters at night; in fact, was forbidden to. For his father, having a grudge against a man in Samoki across the river, had sent a party over to kill him. By some mistake, the wrong man was killed, and it was perfectly well understood in Bontok that the family of the victim were going to take the son’s head in revenge, and were only waiting to catch him out before doing it. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

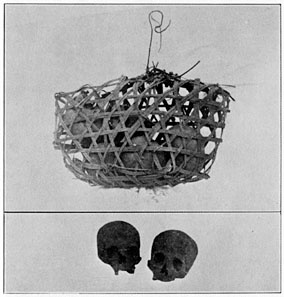

For unknown generations these people have been fierce head-hunters. Nine-tenths of the men in the villages of Bontoc and Samoki wear on the breast the indelible tattoo emblem which proclaims them takers of human heads. The fawi of each ato in Bontoc has its basket containing skulls of human heads taken by members of the ato. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

“These homicides can, however, be atoned without further bloodshed, if the parties interested will agree to it. A more or less amusing instance in kind was recently furnished by the village of Basao, which had in the most unprovoked manner killed a citizen of a neighboring ranchería...The injured village at once made a claim for compensatory damages), and Basao agreed, the villages meeting to discuss the matter. When the claim was presented, Basao, to the unspeakable astonishment and indignation of the offended village, at once admitted the justice of the reclama, and handed over the damages—to-wit, one chicken and pesos six (three dollars). This was an insult to the claimant; for on these occasions it seems that each party takes advantage of the opportunity to tell the other what cowards they are, what thieves and liars, how poor and miserable they are, that they live on sweet potatoes— in short, to recite all the crimes and misdemeanors they have been guilty of from a time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary, this recital being accompanied, of course, by an account of their own virtues, qualities, and wealth.

“The claimants in this case accordingly withdrew, held a consultation, and, returning, declared that in consequence of the insult put upon them the damages would have to be increased, and demanded one peso more! The body is always returned, and the damages cited are for a body accompanied by its head; if the head be lacking, the damages go up, no less than two hundred pesos, a fabulous sum in the mountains.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, PINE FORESTS, BONTOC RICE TERRACES factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Reasons for Bontoc Head Hunting

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The taking of heads is almost invariably an accompaniment of intervillage warfare. They invariably, too, take the heads of all killed on a head-hunting expedition. They have skulls of Spaniards, and also skulls of Igorot, secured when on expeditions of punishment or annihilation with the Spanish soldiers.

For unknown generations these people have been fierce head-hunters. Nine-tenths of the men in the villages of Bontoc and Samoki wear on the breast the indelible tattoo emblem which proclaims them takers of human heads. The fawi of each ato in Bontoc has its basket containing skulls of human heads taken by members of the ato. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The desire for exaltation in the minds of descendants also has a certain influence—young men in quarrels sometimes brag of the number of heads taken by their ancestors, and the prowess or success of an ancestor seems to redound to the courage of the descendants; and it is an affront to purposely and seriously belittle the head-hunting results of a man’s father.

There can be no doubt that head-hunting expeditions are often made in response to a desire for activity and excitement, with all the feasting, dancing, and rest days that follow a successful foray. The explosive nature of a man’s emotional energy demands this bursting of the tension of everyday activities. In other words, the people get to itching for a head, because a head brings them emotional satisfaction.

Bontoc Headhunting Wars

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: En-fa-loknet is the Bontoc word for war, but the expression “na-maka”—take heads—is used interchangeably with it. It is believed that now the people of the two sister villages, Bontoc and Samoki, look on war and head-hunting somewhat as a game, as a dangerous, great sport, though not a pastime. It is a test of agility and skill, in which superior courage and brute force are minor factors. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

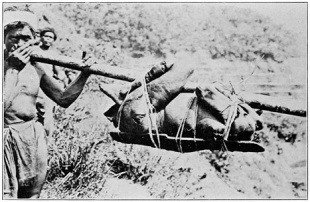

Primarily a village is an enemy of every other village, but it is customary for villages to make terms of peace. Neighboring villages are usually, but not always, friendly. The second village away is usually an enemy. On most of our trips through northern Luzon cargadors and guides could readily be secured to go to the nearest village, but in most cases they absolutely refused to go on to the second village, and could seldom be driven on by any argument or force. The actual negotiations for peace are generally between some two ato of the two interested villages, since the debt of life is most often between two ato.

It now and then happens that of two villages at peace one loses a head to the other. If the one taking the head desires continued peace, some of its most influential men hasten to the other village to talk the matter over. Very likely the other village will say, “If you wish war, all right; if not, you bring us two carabaos, and we will still be friends.” If no effort for peace is made by the offenders, each from that day considers the other an enemy.

After a peace has been canceled the two villages keep up a predatory warfare, with a head lost here and there, and with now and then a more serious battle, until one or the other again sues for peace, and has its prayer granted. In this predatory warfare the entire body of enemies, one or more ato, at times lays in hiding to take a few heads from lone people at their daily toil. Or when the country about a trail is covered with close tropical growth an enemy may hide close above the path and practically pick his man as he passes beneath him. He hurls or thrusts his spear, and almost always escapes with his own life, frequently bursting through a line of people on the trail, and instantly disappearing in the cover below. Should the injured village immediately retaliate, it finds its enemies alert and on guard.

Occasionally a town has a bad strain of blood, and two or three men break away without common knowledge and take heads. The entire body of warriors in the village where those murdered lived promptly rises and pours itself unheralded on the village of the murderers. If these people are not warned the slaughter is terrible—men, women, and children alike being slain. None is spared, except mere babes, unless they belong to the offended village, marriage having taken them away from home. Preceding a known attack on a village it is customary for the women and children to flee to the mountains, taking with them the dogs, pigs, chickens, and valuable household effects. However, Bontoc village, because of her strength, is not so evacuated—she expects no enemy strong enough to burst through and reach the defenseless.

Bontoc Head-Hunting Battles

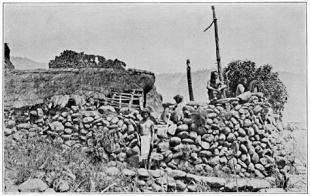

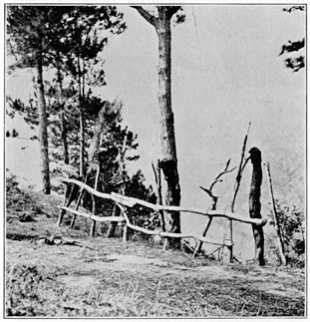

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: At two places near the mountain trail between Samoki and Tulubin is a trellis-like structure called “komis.” It consists of several posts set vertically in the ground, to which horizontal poles are tied, The ceremony of the komis is held before all head-hunting expeditions, except in the unpremeditated outburst of a people to immediately punish the successful foray or ambush of some other. The komis is built along all Bontoc war trails, though no others are known having the “anito” heads. So persistent are the warriors if they have decided to go to a particular village for heads that they often go day after day to the komis for eight or ten days before they are satisfied that no good omens will come to them. If the omens are persistently bad, it is customary for the warriors to return to their ato and hold the mo-gi(ng ceremony, during which they bury under the stone pavement of the fawi court one of the skulls then preserved in the ato. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Men go to war armed with a wooden shield, a steel battle-ax, and one to three steel or wooden spears. It is a man’s agility and skill in keeping his shield between himself and the enemy that preserves his life. Their battles are full of quick, incessant springing motion. There are sudden rushes and retreats, sneaking flank movements to cut an enemy off. The body is always in hand, always in motion, that it may respond instantly to every necessity. Spears are thrown with greatest accuracy and fatality up to 30 feet, and after the spears are discharged the contest, if continued, is at arms’ length with the battle-axes. In such warfare no attitude or position can safely be maintained except for the shortest possible time.

Challenges and bluffs are sung out from either side, and these bluffs are usually “called.” In the last Bontoc-Tulubin foray a fine, strapping Tulubin warrior sung out that he wanted to fight ten men—he was taken at his word so suddenly that his head was a Bontoc prize before his friends could rally to assist him. Rocks are often thrown in battle, and not infrequently a man’s leg is broken or he is knocked senseless by a rock, whereupon he loses his head to the enemy, unless immediately assisted by his friends.

Bontoc Head-Taking

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: There is little formality about the head taking. Most heads are cut off with the battle-ax before the wounded man is dead. Not infrequently two or more men have thrown their spears into a man who is disabled. If among the number there is one who has never taken a head, he will generally be allowed to cut this one from the body, and thus be entitled to a head taker’s distinct tattoo. However, the head belongs to the man who threw the first disabling spear, and it finds its resting place in his ato. If there is time, men of other ato may cut off the man’s hands and feet to be displayed in their ato. Sometimes succeeding sections of the arms and legs are cut and taken away, so only the trunk is left on the field. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Frequently a battle ends when a single head is taken by either side—the victors calling out, “Now you go home, and we will go home; and if you want to fight some other day, all right!” In this way battles are ended in an hour or so, and often in half an hour. However, they have battles lasting half a day, and ten or a dozen heads are taken. Seven villages of the lower Quiangan region went against the scattered groups of dwellings in the Banaue area of the upper Quiangan region in May, 1902. The invaders had seven guns, but the people of Banaue had more than sixty—a fact the invaders did not know until too late. However, they did not retire until they had lost a hundred and fifty heads. They annihilated one of the groups of the enemy, getting about fifty heads, and burned down the dwellings. This is by far the fiercest Igorot battle of which there is any memory, and its ferocity is largely due to firearms.

When a head has been taken the victor usually starts at once for his village, without waiting for the further issue of the battle. He brings the head to his ato and it is put in a small funnel-shaped receptacle, called “sak-olong,” which is tied on a post in the stone court of the fawi.

Bontoc Head-Taking Celebration

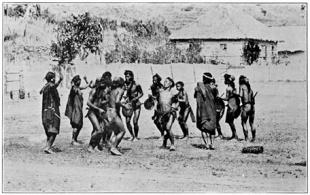

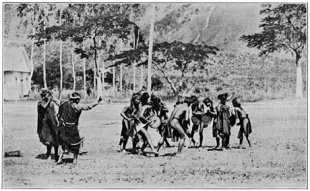

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The entire ato joins in a head-taking ceremony for the day and night; it is called “sedak.” A dog or hog is killed, the greater part of which is eaten by the old men of the ato, while the younger men dance to the rhythmic beats of the gangsa. On the next day, “chaois,” a month’s ceremony, begins. About 7 o’clock in the morning the old men take the head to the river. There they build a fire and place the head beside it, while the other men of the ato dance about it for an hour. All then sit down on their haunches facing the river, and, as each throws a small pebble into the water he says, “Man-isu, hu! hu! hu! Tukukan!”—or the name of the village from which the head was taken. This is to divert the battle-ax of their enemy from their own necks. The head is washed in the river by sousing it up and down by the hair; and the party returns to the fawi where the lower jaw is cut from the head, boiled to remove the flesh, and becomes a handle for the victor’s gangsa. In the evening the head is buried under the stones of the fawi. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

In a head ceremony which began in Samoki May 21, 1903, there was a hand, a jaw, and an ear suspended from posts in the courts of ato Nag-pi, Kawa, and Nak-a-wang, respectively. In each of the eight ato of the village the head ceremony was performed. In their dances the men wore about their necks rich strings of native agate beads which at other dances the women usually wear on their heads. Many had boar-tusk armlets, some of which were gay with tassels of human hair. Their breechcloths were bright and long. All wore their battle-axes, two of which were freshly stained halfway up the blade with human blood—they were the axes used in severing the trophies from the body of the slain.

On the second day the dance began about 4 o’clock in the morning, at which time a bright, waning moon flooded the village with light. At every ato the dance circle was started in its swing, and barely ceased for a month. A group of eight or ten men formedand danced contraclockwise around and around the small circle. Each dancer beat his blood and emotions into sympathetic rhythm on his gangsa, and each entered intently yet joyfully into the spirit of the occasion—they had defeated an enemy in the way they had been taught for generations.

It was a month of feasting and holidays. Carabaos, hogs, dogs, and chickens were killed and eaten. No work except that absolutely necessary was performed, but all people—men, women, and children—gathered at the ato dance grounds and were joyous together. Each ato brought a score of loads of unhusked rice, and for two days women threshed it out in a long wooden trough for all to eat in a great feast. Twenty-four persons, usually all women, lined up along each side of the trough, and, accompanying their own songs by rhythmic beating of their pestles on the planks strung along the sides of the trough, each row of happy toilers alternately swung in and out, toward and from the trough, its long heavy pestles rising and falling with the regular “click, click, thush; click, click, thush!” as they fell rebounding on the plank, and were then raised and thrust into the unhusked rice-filled trough.

After heads have been taken by an ato any person of that ato—man, woman, or child—may be tattooed; and in Bontoc village they maintain that tattooing may not occur at any other time, and that no person, unless a member of the successful ato, may be tattooed.

Display of Bontoc Hunted Heads

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: After the captured head has been in the earth under the fawi court of Bontoc about three years it is dug up, washed in the river, and placed in the large basket, the so-lonang, in the fawi, where doubtless it is one of several which have a similar history. At such time there is a three-day’s ceremony, called “min-pa-fakal is nan moking.” It is a rest period for the entire village, with feasting and dancing, and three or four hogs are killed. The women may then enter the fawi; it is said to be the only occasion they are granted the privilege. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

In the fawi of ato Sigichan there are at present three skulls of men from Sagada, one of a man from Balugan, and one of a man and two of women from Baliwang. Probably not more than a dozen skulls are kept in a fawi at one time. The final resting place of the skull is again under the stones of the fawi. Samoki does not keep the skull at all; it remains where buried under the ato court. As was stated before, a skull is generally buried under the stones of the fawi court whenever the omens are such that a proposed head-hunting expedition is given up. They are doubtless, also, buried at other times when the basket in the fawi becomes too full. Sigichan has buried twenty-eight skulls in the memory of her oldest member—making a total of thirty-five heads taken, say, in fifty years. Three of these were men’s heads from Ankiling, nine were men’s heads from Tukukan, three were men’s heads from Barlig, three were men’s heads and four women’s heads from Sabangan, and six were men’s heads from Sadanga. During this same period Sigichan claims to have lost one man’s head each to Sabangan and Sadanga.

No small children’s skulls can be found in Bontoc, though some other head-hunters take the heads even of infants. In fact, the men of Bontoc say that babes and children up to about 5 years of age are not killed by the head-hunter. If one should take a child’s head he would shortly be called to fate by some watchful pinteng in language as follows: “Why did you take that babe’s head? It does not understand war. Pretty soon some village will take your head.” And the pinteng is supposed to put it into the mind of some village to get the head of that particularly cruel man.

Sun Man and Moon Woman — Origin of Headhunting

According to a Bontoc folk tale that explains the origin of headhunting: The Moon, a woman called “Ka-bi-gat,” was one day making a large copper cooking pot. The copper was soft and plastic like potter’s clay. Ka-bi-gat held the heavy sagging pot on her knees and leaned the hardened rim against her naked breasts. As she squatted there—turning, patting, shaping, the huge vessel—a son of the man Chal-chal, the Sun, came to watch her. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

This is what he saw: The Moon dipped her paddle, called “pip-i,” in the water, and rubbed it dripping over a smooth, rounded stone, an agate with ribbons of colors wound about in it. Then she stretched one long arm inside the pot as far as she could. “Tub, tub, tub,” said the ribbons of colors as Ka-bi-gat pounded up against the molten copper with the stone in her extended hand. “Slip, slip, slip, slip,” quickly answered pip-i, because the Moon was spanking back the many little rounded domes which the stone bulged forth on the outer surface of the vessel. Thus the huge bowl grew larger, more symmetrical, and smooth.

Suddenly the Moon looked up and saw the boy intently watching the swelling pot and the rapid playing of the paddle. Instantly the Moon struck him, cutting off his head. Chal-chal was not there. He did not see it, but he knew Ka-bi-gat cut off his son’s head by striking with her pip-i. He hastened to the spot, picked the lad up, and put his head where it belonged—and the boy was alive.

Then the Sun said to the Moon: “See, because you cut off my son’s head, the people of the Earth are cutting off each other’s heads, and will do so hereafter.” And it is so,” the story-tellers continue; “they do cut off each other’s heads.”

Bontoc Mercy Killing and Murders

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: Igorot badly injured in war or elsewhere are usually killed at their own request. In May, 1903, a man from Maligkong was thrown to the earth and rendered unconscious by a heavy timber he and several companions brought to Bontoc for the school building. His companions immediately told Captain Eckman to shoot him as he was “no good.” I can not say whether it is customary for the Igorot to weed out those who faint temporarily—as the fact just cited suggests; however, they do not kill the feeble aged, and the presence of the insane and the imbecile shows that weak members of the group are not always destroyed voluntarily. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “It must be very hard to get at what is going on behind the eyes of his native parishioners. For example, shortly before our arrival, a young Igorot had been confirmed by Bishop Brent. Now this boy was attending school, and in the school was another boy from a ranchería that had taken a head from the ranchería of the recent convert. When the latter’s people learned of this, they sent for their boy, the recent convert, the Monday after confirmation, held a cañao (killing a pig, dancing, and so on), and sent him back resolved to take vengeance by killing the boy from the offending ranchería. Accordingly, on Thursday, at night, the victim-to-be was lured behind the school-house under the pretext of getting a piece of meat, and, while his attention was held by an accomplice with the meat, the avenger came up behind, killed him, and was about to take his head when people came up and arrested him. This case illustrates the difficulties to be met in civilizing these people. Legally, under our view, this boy was a murderer; under his own customs and traditions, he had done a commendable thing. When the boys’ school was first opened, they used to take their spears and shields into the room with them; this proving not only troublesome, but dangerous, their arms are now taken away from them every morning, and returned after school closes. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Many people came to see Governor Evans this day, among them a young man begging for the release of a prisoner held for murder. He really could not see why the man should not be set free, and sat patiently for two hours on his haunches, every now and then holding up and presenting a white rooster, which he was offering in exchange. The matter was not one for discussion at all, but Evans was as patient as his visitor, paying no attention to him whatever. Whenever the pleader could catch Evans’s eye, up would go the rooster and be appealingly held out. Only two or three weeks before, a private of Constabulary had shot and killed the head man of Tinglayan some miles north of Bontok. He was arrested, of course, and when we came through was awaiting trial. But a deputation had come in to wait on Mr. Forbes, and ask for the slayer, so that they might kill him in turn, with proper ceremonies. Naturally the request was refused; but these people could not understand why, and went off in a state of sullen discontent. Here, again, was a conflict between our laws, the application of which we are bound to uphold, and native customs, having the force of law and so far regarded by the highlanders as meeting all necessities.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026