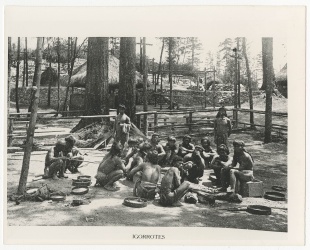

IGOROT

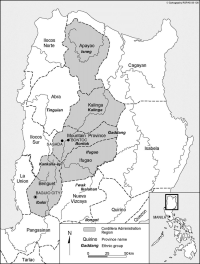

Igorot is a term traditionally used by outsiders to describe the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera in northern Luzon. Sometimes today referred to as Cordilleran peoples, Igorot is broad ethnic grouping made up of nine or ten major ethnolinguistic communities: 1) Bontoc, 2) Ibaloi, 3) Ifugao, 4) Kalanguya (Ikalahan), 5) Isinai, 6) Isneg, 7) Itneg (Tinguian), 8) Ilongot (Bugkalot), 9) Kalinga, and 10) Kankanaey. Ilocano describes one of the largest Igorot language groups. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to Philippine Statistics Authority there were 1,854,556 Igorot in in 2015. Their languages belong to the Northern Luzon subgroup of Philippine languages, which is part of the wider Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) language family. A 2014 genetic study found that the Kankanaey—an Igorot subgroup from Mountain Province—and, by extension, other Cordillera peoples, descend almost entirely from the ancient Austronesian migration that originated in Taiwan between roughly 3000 and 2000 B.C..

The term Igorot is derived from the root word golot, meaning “mountain.” Igolot translates to “people from the mountains,” a label historically applied to various highland groups in northern Luzon. During the Spanish colonial period, the name appeared in several forms—Igolot, Ygolot, and Igorrote—reflecting Spanish orthographic conventions. Many Cordillera peoples prefer the endonyms Ifugao or Ipugaw, which also mean “mountain people,” as Igorot is considered by some to carry mildly pejorative connotations, with the notable exception of the Ibaloy. The Spanish term Ifugao was borrowed from the lowland Gaddang and Ibanag groups.

RELATED ARTICLES:

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

BUGKALOT (ILONGOT): LIFE, CULTURE, CUSTOMS, SOCIETY, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

ILONGOT IN THE 1910s factsanddetails.com

KALINGA: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

KALINGA IN 1910 factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC REGION IN THE EARLY 1900s: GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY, DISEASES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

Igorot and Northern Luzon Groups

The Igorots, including those of the Cordillera of north-central Luzon and the Caraballo Range and Sierra Madre, are far from homogeneous. They divide into eight linguistic groups and four broad cultural types. The southern group includes the Ibaloi and the Kankanai. Their gold mines attracted more concerted Spanish attention, exposing them to lowland influences such as upper garments for women. Elsewhere in the highlands, women traditionally went bare-chested. The northern group includes swidden-farming, relatively egalitarian societies of the northern Kalinga, Isneg (or Apayao), and Tinggianes, meaning "highlanders," a name that used to apply far more broadly. The Ilongot ("forest people," see Ilongot) comprise the southeastern group and are known for their extreme conservatism and isolationism. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Igorots are often broadly divided into two general groupings. The larger population occupies the southern, central, and western Cordillera and is renowned for sophisticated rice-terrace agriculture. The smaller grouping lives in the eastern and northern areas. Before Spanish colonisation, these communities did not view themselves as a single, unified ethnic group. Most Igorot reside in the Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, and Cagayan Valley. Languages spoken include Bontoc, Ilocano, Itneg, Ibaloi, Isnag, Kankanaey, Bugkalot, Kalanguya, Isinai, as well as Filipino and English. Religious beliefs range from Christianity—both Catholicism and Protestantism—to indigenous animist traditions, with small Muslim communities also present.

Not all groups in northern Luzon are Igorots. The Ilocano (Ilokano/Iloko) dominate the valleys and coastal regions of northern Luzon. They are the third-largest ethnolinguistic group in the Philippines, numbering over 10 million and originate from the Ilocos Region in northwestern Luzon. Known for their industriousness, frugality, and strong family ties, they are predominantly Christian, with a rich culture featuring inabel weaving, unique cuisine like pinakbet and bagnet.

Gaddang People are a valley not a highlands people that live in northern Luzon. Also known as the Gadan, Ga'dang, Gaddanes, Iraya, Pagan Gaddang, and Yrraya, they live in the middle Cagayan Valley in northern Luzon in the Philippines. "Gaddang" refers to the Christianized Gaddang, who have largely been assimilated into Ilocano or general Filipino society, as well as the Gaddang that practice traditional religions. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the population of Cagayan Gaddang was 66,000 in the early 2020s. About 90 percent are Christian, with 10 to 50 percent being Protestant Evangelicals. In the 1960s, there were approximately 2,500 animist Gaddang and 25,000 Christian Gaddang. In 1975, their combined number was estimated at 17,500, suggesting continued assimilation into mainstream Filipino society. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Joshua Project]

Luzon Ethnic Groups by Linguistic Classification

Ilokano (Ilcano, Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, and La Union)

Northern Cordilleran

Isneg (northern Apayao)

Ibanagic

1) Ibanag (Cagayan and Isabela)

2) Gaddangic

a) Gaddang (Nueva Vizcaya and Isabela)

b) Ga'dang (Mountain Province, Ifugao, Kalinga Province, Aurora and Nueva Vizcaya)

c) Itawis (southern Cagayan and Apayao)

d) Yogad (Isabela)

Central Cordilleran

Isinai (northern Nueva Vizcaya, north Nueva Ecija, northwest Aurora)

Kalinga–Itneg

1) Kalinga (Kalinga)

2) Itneg (Abra)

Nuclear

1) Ifugao (Ifugao)

2) Balangao (eastern Mountain Province)

3) Bontok (central Mountain Province)

4) Kankanaey (western Mountain Province, northern Benguet)

Southern Cordilleran

Ibaloi (southern Benguet, east La Union, west Nueva Vizcaya)

Kalanguya (Kallahan) (eastern Benguet, Ifugao, northwestern Nueva Vizcaya, north Nueva Ecija)

1) Kalanguya Keley-i

2) Kalanguya Kayapa

3) Kalanguya Tinoc

Karao (Karao, Bokod, Benguet)

Bugkalot (Ilongot) (eastern Nueva Vizcaya, western Quirino, north Nueva Ecija, northwest Aurora)

Pangasinan (Pangasinan)

The Ilocano language serves as a lingua franca for different Igorot groups. Many Cordilleran languages have varying dialect continuums through different tribes and localities. Igorot groups also use Ilocano to communicate with ethnic Ilocanos and other second-language speakers, such as the Ibanags. In addition to Ilocano, they speak Tagalog and English as lingua francas.

Igorot History

Most scholars believe that the peoples of the North Luzon Highlands originated in southern China or Taiwan and migrated from Taiwan to present-day Philippines and moved through northern Luzon via the Cagayan River Valley. Reliable historical documentation begins with Spanish contact. Ferdinand Magellan claimed the Philippines for Spain in 1521. The first Spanish encounter with northern Luzon occurred in 1572, when Juan de Salcedo — grandson of Miguel de Legazpi, who occupied the Manila area in 1565—explored the Ilocos coast. During this expedition, Salcedo learned of gold deposits in the North Luzon Highlands, sparking Spanish interest in the southern portions of the mountain region. [Source: Robert Lawless, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Gold found in Igorot lands was a major attraction for the Spanish. Long before colonisation, the Igorots traded gold in Pangasinan and used it to obtain basic goods. Spanish ambitions in the region were driven by both the lure of gold and the desire to Christianise the highland peoples. From 1572 onward, Spanish expeditions searched for gold, entering Benguet Province with the aim of exploiting its resources. Yet the Igorots’ sustained resistance allowed them to remain largely outside Spanish control, frustrating colonial authorities and keeping much of the gold beyond their reach. In later years, Igorots also served as mercenaries and scouts during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War. [Source: Wikipedia]

American writer Samuel E. Kane documented his life among the Bontoc, Ifugao, and Kalinga after the Philippine–American War in Thirty Years with the Philippine Head-Hunters (1933). The first American school for Igorot girls was established in Baguio in 1901 by Alice McKay Kelly. Kane credited Dean C. Worcester with doing more than anyone else to end headhunting and foster peace among traditionally hostile tribes. Reflecting on Igorot life, Kane wrote that “there is a peace, a rhythm and an elemental strength in the life…which all the comforts and refinements of civilization can not replace,” while warning that within fifty years, little might remain to remind young Igorots of the era when “the drums and ganzas of the head-hunting canyaos resounded throughout the land.”

In 1903, missionary bishop Charles Brent travelled through northern Luzon to direct Christian missions among the Igorots. A mission church was established for the Bontoc in Mountain Province, and missionaries produced the first Igorot grammars, later published by the government. During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Igorots fought against Japanese forces. Donald Blackburn’s World War II guerrilla unit included a strong Igorot core, and a young Igorot woman, Naomi Flores, played a key role in the Miss U Spy Ring. In early September 1945, General Tomoyuki Yamashita surrendered to Filipino and American forces in Kiangan, Ifugao, where a shrine was later built to mark the event. On June 18, 1966, Republic Act No. 4695 divided the old Mountain Province into four separate provinces: Benguet, Ifugao, Kalinga-Apayao, and Mountain Province. Ifugao and Kalinga-Apayao were placed under the Cagayan Valley region, while Benguet and Mountain Province were assigned to the Ilocos Region.

In recent decades highland peoples have faced diverse and increasing pressures from lowland society. The most threatening issues through the early 1990s were dam projects that intended to flood ancestral valleys and fighting between the New People's Army (NPA) guerrillas and the Philippine government. These issues have been less prevalent since the early 1990s. Agrarian reform has affected few people because their landholdings tend to be very small. However, the government has begun to recognize the highland peoples' rights to their ancestral lands. In the past, 87 percent of the land in the Cordillera region was classified as state property, much of which was awarded by politicians to logging companies. As elsewhere, international tourism has been a mixed blessing, eroding much of traditional culture while promoting certain aspects of it. In some areas, the rice terraces are being neglected as young people, attracted by work in cities or abroad, are less willing to stay in their home villages and do the arduous work of maintaining the terraces. [Source: A. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

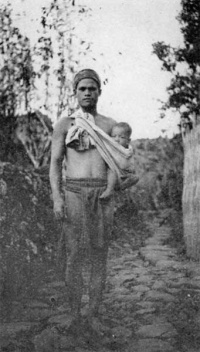

Where the Igorot Lived in 1905

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The mountain country in northern Luzon — the “temperate zone of the Tropics” — is the habitat of the Igorot. From the western coastal hill area the mountains rise abruptly in parallel ranges lying in a general north and south direction, and they subside only in the foothills west of the great level bottom land bordering the Rio Grande de Cagayan. The Cordillera Central is as fair and about as varied a mountain country as the tropic sun shines on. It has mountains up which one may climb from tropic forest jungles into open, pine-forested parks, and up again into the dense tropic forest, with its drapery of vines, its varied hanging orchids, and its graceful, lilting fern trees. It has mountains forested to the upper rim on one side with tropic jungle and on the other with sturdy pine trees; at the crest line the children of the Tropics meet and intermingle with those of the temperate zone. There are gigantic, rolling, bare backs whose only covering is the carpet of grass periodically green and brown. There are long, rambling, skeleton ranges with here and there pine forests gradually creeping up the sides to the crests. There are solitary volcanoes, now extinct, standing like things purposely let alone when nature humbled the surrounding earth. There are sculptured lime rocks, cities of them, with gray hovels and mansions and cathedrals. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The mountains present one interesting geologic feature. The “hiker” is repeatedly delighted to find his trail passing quite easily from one peak or ascent to another over a natural connecting embankment. On either side of this connecting ridge is the head of a deep, steep-walled canyon; the ridge is only a few hundred feet broad at base, and only half a dozen to twenty feet wide at the top. These ridges invariably have the appearance of being composed of soft earth, and not of rock. They are Page 25appreciated by the primitive man, who takes advantage of them as of bridges.

The mountains are well watered; the summits of most of the mountains have perpetual springs of pure, cool waters. On the very tops of some there are occasional perpetual water holes ranging from 10 to 100 feet across. These holes have neither surface outlet nor inlet; there are two such within two hours of Bontoc pueblo. They are the favorite wallowing places of the carabao, the so-called “water buffalo,”2 both the wild and the half-domesticated animals.

The mountain streams are generally in deep gorges winding in and out between the sharp folds of the mountains. Their beds are strewn with boulders, often of immense size, which have withstood the wearing of waters and storms. During the rainy season the streams racing between the bases of two mountain ridges are maddened torrents. Some streams, born and fed on the very peaks, tumble 100, 500, even 1,500 feet over precipices, landing white as snow in the merciless torrent at the mountain base. During the dry season the rivers are fordable at frequent intervals, but during the rainy season, beginning in the Cordillera Central in June and lasting well through October, even the natives hesitate often for a week at a time to cross them.

Igorot Highlanders of Northern Luzon in 1910

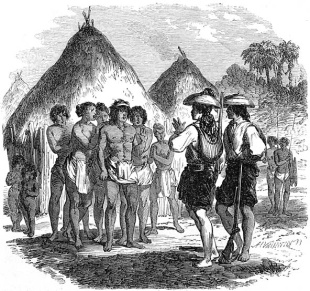

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “Most of our people do not know that a very large fraction of the inhabitants of the Philippines consists of the so-called wild men, and that of these the greatest group or collection is found in the mountains of Northern Luzon. These mountaineers or highlanders constitute perhaps, all other things being equal, as interesting a body of uncivilized people as is to be found on the face of the earth to-day. The Spaniards, of course, soon discovered their existence, the first mention of them being made by De Morga, in his “Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas” (1609). He speaks of them as inhabiting the interior of a rough mountainous country, where are “many natives who are not pacified, nor has anyone gone into their country, who call themselves Ygolotes,” Here we have the first form, the classic form according to Retana, of the word now universally written Igorrote, or in English Igorot. The word itself means “highlanders,” golot being a Tagalog word for “mountain,” and I a prefix meaning “people of.” De Morga mentions the “Ygolotes” as owning rich mines of gold and silver, which “they work as there is need,” and he goes on to say that in spite of all the diligence made to know their mines, and how they work and improve them, the matter has come to naught, “because they are cautious with the Spaniards who go to them in search of gold, and say they keep it better guarded under ground than in their houses.” [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“The Spaniards at a very early date sent armed exploring parties through the highlands and maintained garrisons here and there down to our own time. But they never really held the country. The Church, too, early entered this territory, the field being given over to the Dominicans, who furnished many devoted missionaries to the cause. But here, too, failure must be recorded in respect of permanency of results in the really wild parts of the Highlands. It has remained for our own Government to get a real hold of the people of these regions, to win their confidence, command their respect, and exact their obedience in all relations in which obedience is proper and just.

The indispensable material condition of success was to make the mountain country accessible. Only those who have had the fortune to travel through this country can realize how difficult this endeavor has been and must continue to be, chiefly because of the great local complexity of the mountain system, but also because of the severely destructive storms of this region, with consequent torrential violence of the streams affected. But little money, too, can be, or has been, spent for the necessary road-work. In spite of the difficulties involved, however, a system of road-making has been set on foot, the labor needed being furnished by the highlanders themselves in lieu of a road tax.

“The Mountain Province itself is the outcome of the difficulties encountered in governing the wild tribes so long as these were left in provinces where either their interests were not paramount, or else the difficulties of administration were unduly costly or difficult. Established in 1908, it has a Governor, and each of its seven sub-provinces a Lieutenant-Governor, the sub-province as far as possible including people of one and of only one tribe. The creation of this province was a great step forward in promoting the welfare of the highlanders.

“A word must be said here in explanation of the nomenclature of the mountain tribes. Generically, having in mind the meaning of the word, they are all Igorots. But it is the practice to distinguish the various elements of this great family by different names, restricting the term “Igorot” to special branches, as Benguet Igorot, Bontok Igorot, meaning those who live in Benguet or Bontok. The other members are known as Ifugao, Ilongot, Kalinga, and so on.”

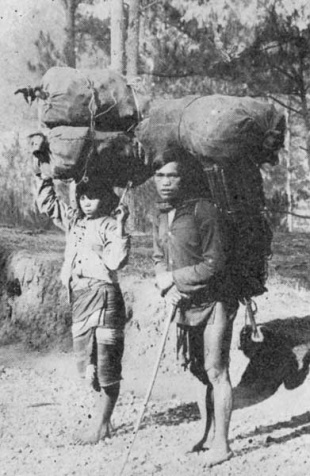

Annual Inspection of the Northern Luzon Mountain Tribes in 1910

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “ Every year Mr. Worcester makes a formal tour of inspection through the Mountain Province to note the progress of the trails and roads, to listen to complaints, to hear reports, devise ways and means of betterment and in general to see how the hillmen are getting on. This tour is a very great affair to the highlanders, who are assembled in as great numbers as possible at the various points where stops are made; during the stay...at the points of assemblage, the wild people are subsisted by the Government. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“The trip is long and hard, nor is it altogether free from danger. Preparations have to be made two months ahead to have forage for animals, and food for human beings, at the expected halts, while everything eaten by man or beast on the way must be carried by the cargadores (bearers) who accompany the column, since living off the country is in general impossible.”

In one area one hundred and sixty bridges are crossed in the drop, and at times a rise will wash out not only the bridges, but all semblance of a road...A bamboo bridge had been built across the stream a few days before so that our cars might cross, but yesterday’s rain had washed it down, and would we try to cross on rafts? We looked at the rafts, bamboo platforms built over large bancas (canoes, double-enders cut out of a single log), the bamboos being lashed together with bejuco (rattan, the native substitute for nails), and decided that no self-respecting motor would stand such transportation, but would go to the bottom first by overturning. So we got our stuff aboard the rafts, were poled over, and made the rest of the journey to Tayug, our first considerable halt, in carromatas (the native two-wheeled, springless cart). Fortunately the distance was short, the carromata being an instrument of torture happily overlooked by the Spanish Inquisition.

“At Tayug a great concourse of people welcomed us, with arches, flags, and decorations. The presidencia, or town hall, was filled with the notabilities, and Mr. Forbes was presented with an address by one of the señoritas. Suitable answer having been made, we adjourned, the men first, the women following when we had done, according to native custom, to the side rooms, where a surprisingly good tiffin had been got ready for us, venison, chickens, French rolls, dulces (sweets), whiskey and soda, Heaven knows what else, to which, all unwitting of our doom, we did full justice. About two miles beyond Tayug lies San Francisco, the initial point of our real mounted journey. The people along this part of the road had simply outdone themselves in the matter of arches, there being one at every hundred yards almost. At San Francisco the crowd was greater than at Tayug; and here was set out for us another sumptuous tiffin, in a house built the day before for this very purpose, of bamboo and nipa palm.”

Development of The Luzon Highlands in the 1910s

The United States acquired the Philippines from Spain via the Treaty of Paris in 1898, for $20 million following the Spanish-American War. Formal control began with military rule after the capture of Manila, leading to the Philippines-American War (1899–1902). On American development in the Philippines highlands in the early 20th century, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: All great things are simple! The first thing was to see the people himself; and then came the beginning of the solution, to push practicable roads and trails through the country. Once these established, communication and interchange would follow, and the way would be cleared for the betterment of relations and the removal of misunderstandings. Today an American may ride through the country alone, unarmed and unmolested; twenty years ago a Spaniard trying the same thing would have lost his head within the first five miles. And this difference is fundamentally due to the fact, already mentioned, of the honesty of our relations with these simple mountaineers. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“We have their confidence and their esteem and their respect, and this in spite of the necessity under which our authorities have constantly labored of punishing them when necessary and of insisting upon law and order wherever our jurisdiction prevails. The lesson has been hard to learn, but it has been driven home. The truth of the matter is, that a great missionary work has been begun; missionary not in the limited sense of forcing upon the understanding of a yet circumscribed people a religion unintelligible to them, but in the sense of teaching peace and harmony, respect for order, obedience to law, regard for the rights of others.”

“The success of American rule over the non-Christian tribes of the Philippines is chiefly due to the friendly feeling which has been brought about. “The wild man has now learned for the first time that he has rights entitled to a respect other than that which he can enforce with his lance and his head-axe. He has found justice in the courts. His property and his life have been made safe, and the American governor, who punishes him sternly when he kills, is his friend and protector so long as he behaves himself.”

Very extensive lines of communication have been opened up by the building of roads and trails and the clearing of rivers. A good state of public order has been established. Head-hunting, slavery, and piracy are now very rare. The liquor traffic has been almost completely suppressed. Life and property have been rendered comparatively safe, and in much of the territory entirely so. In many instances, the wild men are being successfully used to police their own country. Agriculture is being developed. Unspeakably filthy towns have been made clean and sanitary. The people are learning to abandon human sacrifices and animal sacrifices and to come to the doctor when injured or ill. Numerous schools have been established and are in successful operation. The old sharply drawn tribal lines are disappearing. Bontoc Igorots, Ifugaos, and Kalingas now visit each other’s territory. At the same time that all of this has been accomplished, the good-will of the people themselves has been secured. They are outspoken in their appreciation of what has been done for them and in their expression of the wish that American rule should continue. They would be horror-stricken at the thought of being turned over to Filipino control.”

Dislike and Suspicion of Luzon Highlanders by Lowland Filipinos in the 1910s

Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “No greater disaster could befall these highlanders to-day than a change entailing a diminution of the interest and sympathy felt for them at the seat of government. It is best to be plain about this matter: the Filipinos of the lowlands dislike the highlander as much as they fear and dread him. They apparently can not bear the idea that but three or four hundred years ago they too were barbarians; for this reason the consideration of the highlander is distasteful and offensive to them. The appropriations of the Philippine Assembly for the necessary administration of the Mountain Province are none too great; they would cease entirely could the Assembly have its own way in the matter. The system of communications, so well begun and already so productive of happy results, would come to an end. To turn the destiny of the highlander over to the lowlander is, figuratively speaking, simply to write his sentence of death; to condemn as fair a land as the sun shines on to renewed barbarism. We are shut up to this conclusion, not by theoretical considerations, but by experience. The matter is worth examining a little closely, covering, as it does, not only the hill tribes, but non-Christians everywhere else. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

Consider for a moment the facts set out in the following extracts: “With rare exceptions, the Filipinos are profoundly ignorant of the wild men and their ways. They seem to have failed to grasp the fact that the non-Christians, who have been contemptuously referred to in the Filipino press as a ‘few thousand savages asking only to be let alone,’ number approximately a million and constitute a full eighth of the population of the Archipelago.”

“The average hillman hates the Filipinos on account of the abuses which his people have suffered at their hands, and despises them because of their inferior physical development and their comparatively peaceful disposition, while the average Filipino who has ever come in close contact with wild men despises them on account of their low social development, and, in the case of the more warlike tribes, fears them because of their past record for taking sudden and bloody vengeance for real or fancied wrongs.”

“It is impossible to avoid plain speaking if this question is to be intelligently discussed; and the hard fact is, that wherever the Filipinos have come in close contact with the non-Christian inhabitants, the latter have almost invariably suffered at their hands grave wrongs, which the more warlike tribes, at least, have been quick to avenge. Thus a wall of prejudice and hatred has been built up between the Filipinos and the non-Christian tribes. It is a noteworthy fact that hostile feeling toward the Filipinos is strong even among people like the Tinguians who, barring their religious beliefs, are in many ways as highly civilized as are their Ilocano neighbors.”

“After Apayao was established as a sub-province of Cagayán and the duty of providing funds for the maintenance of its government was explicitly imposed upon the provincial board of that province, the governor stated to me that, in his opinion, it would be useless to make the necessary expenditure, and that, in his opinion, it would be better to kill all the savages in Apayao! As they number some 52,000, this method of settling their affairs would have been open to practical difficulties, apart from any humanitarian consideration!”

Igorot Crimes, Punishments and Tests by Ordeal in 1905

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: Theft, lying to shield oneself in some criminal act, assault and battery, adultery, and murder are the chief crimes against Igorot society. There are tests to determine which of several suspects is guilty of a crime. One of these is the rice-chewing test. The old men of the Page ato interested assemble, in whose presence each suspect is made to chew a mouthful of raw rice, which, when it is thoroughly masticated, is ejected on to a dish. Each mouthful is examined, and the person whose rice is the driest is considered guilty. It is believed that the guilty one will be most nervous during the trial, thus checking a normal flow of saliva. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Another is a hot-water test. An egg is placed in an olla of boiling water, and each suspect is obliged to pick it out with his hand. When the guilty man draws out the egg the hot water leaps up and burns the forearm. There is an egg test said to be the surest one of all. A battle-ax blade is held at an angle of about 60 degrees, and an egg is placed at the top in a position to slide down. Just before the egg is freed from the hand the question is asked “Is Liod (the name of the man under trial) guilty?” If the egg slides down the blade to the bottom the man named is innocent but if it sticks on the ax he is guilty.

There is also a blood test employed in Bontoc village, and also to the west, extending, it is said, into Lepanto Province. An instrument consisting of a sharp spike of iron projecting about one-sixteenth of an inch from a handle with broad shoulders is placed against the scalp of the suspects and the handle struck a sharp blow. The projecting shoulder is supposed to prevent the spike from entering the scalp of one farther than that of another. The person who bleeds most is considered guilty—he is “hot headed.”

I was once present at an Igorot trial when the question to be decided was whether a certain man or a certain woman had lied. The old men examined and cross-questioned both parties for fully a quarter of an hour, at which time they announced that the woman was the liar. Then they brought a test to bear evidence in binding their decision. They killed a chicken and cut it open. The gall was found to be almost entirely exposed on the liver—clearly the woman had lied. She looked at the all-knowing gall and nodded her acceptance of the verdict. If the gall had been hidden by the upper lobe of the liver, the verdict would not have been sustained.

If a person steals unhusked rice, the injured party may take a fields from the offender. If a man is found stealing pine wood from the forest lands of another, he forfeits not only all the wood he has cut but also his working ax. The penalty for the above two crimes is common knowledge, and if the crime is proved there is no longer need for the old men to make a decision—the offended party takes the customary retributive action against the offender.

Cases of assault and battery frequently occur. The chief causes are lovers’ jealousies, theft of irrigating water during a period of drought, and dissatisfaction between the heirs of a property at or shortly following the time of inheritance. It is customary for the old men of the interested ato to consider all except common offenses unless the parties settle their differences without appeal. A fine of chickens, pigs, fields, sometimes even of carabaos, is the usual penalty for assault and battery.

Adultery is not a common crime. I was unable to learn that the punishment for adultery was ever the subject for a council of the old men. It seems rather that the punishment—death of the offenders—is always administered naturally, being prompted by shocked and turbulent emotions rather than by a council of the wise men. In Igorot society the spouse of either criminal may take the lives of both the guilty if they are apprehended in the crime. Today the group consciousness of the penalty for adultery is so firmly fixed that adulterers are slain, not necessarily on the spur of the moment of a suspected crime but sometimes after carefully laid plans for detection. A case in question occurred in Suyak of Lepanto Province. A man knew that his faithless wife went habitually at dusk with another man to a secluded spot under a fallen tree. One evening the husband preceded them, and lay down with his spear on the tree trunk. When the guilty people arrived he killed them both in their crime, thrusting his spear through them and pinning them to the earth. Some Igorots brought down to the Manila carnival of 1912 were forced, at the request of Filipino authorities, to put on trousers. This was not for comfort’s sake, nor yet for decency’s, for the bare human skin is no uncommon sight in Manila. Apparently, the Filipinos of Manila were unwilling to let the world note that their cousins of the mountains were still in the naked state.

Igorot and the American Human Zoo

In 1904, some Igorot people were brought to the United States for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where they built an “Igorot Village” in the Philippine Exposition, one of the fair’s most popular attractions. Dubbed a “human zoo”, the Igorot participants were reportedly forced to eat dogs daily for audiences, despite the fact that such practices were rare and ritual-based in the Philippines. This staged performance is widely believed to have helped create the enduring stereotype of Filipinos as dog eaters. [Source: Wikipedia]

At the time of the exposition, the Philippines had just become a colony of the U.S. St. Louis native T. S. Eliot visited the exhibit and later wrote the short story “The Man Who Was King” (1905), inspired in part by the tribal dances. In 1905, fifty Igorots were exhibited at a Brooklyn amusement park, eventually falling under the control of showman Truman Hunt, who traveled across America with the group.

Maura was a teenage Igorot girl taken to the United States for the 1904 St. Louis exposition. She died of pneumonia just days before the St. Louis World’s Fair officially opened. After Maura’s death, her body was sued in experiments conducted by Czech anthropologist Aleš Hrdlička, who spent decades collecting thousands of human body parts—including brains—for the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). His so-called “racial brain collection” includes remains from around 1,200 Filipinos, some of whom were brought to the United States for the 1904 exposition. One of the brains in the collection is believed to have belonged to Maura. [Source: Claire Healy, Nicole Dungca Washington Post, Michelle De Pacina, NextShark, August 19, 2023]

After Spanish-American War, the U.S. reportedly became "fascinated by the natives of the newly acquired territory, which led to the development of anthropological exhibits showcasing what life was like in the Philippines." In total, there are reportedly 255 brains stored at the Smithsonian NMNH from individuals originating in various countries, including the Philippines, Malaysia, and Japan. These findings were brought to light in an investigative report published by The Washington Post titled “The Smithsonian’s ‘Bone Doctor’ Scavenged Thousands of Body Parts.” Following its release, the Smithsonian announced that it is coordinating with Philippine authorities, including the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP), to repatriate the remains of 64 individuals. Among the remains are the brains of four Filipinos. “In adherence with today’s standards of ethical museum practice, the NMP accepts and supports this effort of the Smithsonian NMNH to do the right thing and facilitate the Filipino remains home as a way of rectifying this unfortunate situation,” the organization said.

Igorot in Marcos Years

After Ferdinand Marcos declared martial lawChico River Dam Project in 1972, the Cordillera region became heavily militarised following strong local opposition to the government’s near Sadanga in Mountain Province and Tinglayan in Kalinga. Frustrated by repeated delays caused by resistance on the ground, Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 848 in December 1975, grouping the municipalities of Lubuagan, Tinglayan, Tanudan, and Pasil into a “Kalinga Special Development Region” (KSDR) in an attempt to weaken opposition to the Chico IV dam. [Source: Wikipedia]

Under martial law powers that allowed warrantless arrests, the 60th Philippine Constabulary Brigade detained at least 150 residents by April 1977. Detainees were accused of subversion, obstructing government projects, and other alleged offences, including boycotting the October 1976 constitutional referendum. Those arrested included tribal pangat (leaders or elders), young couples, and, in one documented case, a 12-year-old child. By December 1978, sections of the Chico IV project area had been declared “free fire zones,” effectively turning them into no-man’s-land where troops could fire at animals or unauthorised civilians at will.

On April 24, 1980, military forces under the Marcos regime assassinated Macli-ing Dulag, a pangat of the Butbut tribe in Kalinga. His killing became a turning point, marking the first time the mainstream Philippine press openly criticised Marcos and the military, and it helped strengthen a broader sense of Igorot identity.

Following the fall of the Marcos regime in the 1986 People Power Revolution, the administration of President Corazon Aquino negotiated a ceasefire with the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army (CPLA), the region’s main indigenous armed group led by Conrado Balweg. On September 13, 1986, the government and the CPLA sealed a sipat, or indigenous peace pact, known as the Mount Data Peace Accord, formally ending hostilities in the Cordilleras.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026