BONTOC IN 1905

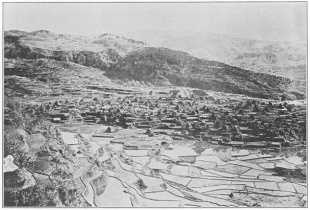

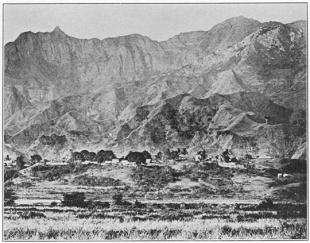

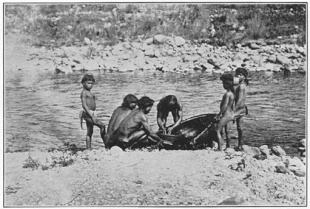

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: Bontoc, and Samoki villages, in all essentials typical of villages in the Bontoc area, lie in the mountains in a roughly circular pocket... A perfect circle about a mile in diameter might be described within the pocket. It is bisected fairly accurately by the Chico River, coursing from the southwest to the northeast. Its altitude ranges from about 2,750 feet at the river to 2,900 at the upper edge of Bontoc village, which is close to the base of the mountain ridge at the west, while Samoki is backed up against the opposite ridge to the southeast. The river flows between the villages, though considerably closer to Samoki than to Bontoc. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Bontoc lies compactly built on a sloping piece of ground, roughly about half a mile square. Through the village are two water-cut ravines, down which pour the waters of the mountain ridge in the rainy season, and in which, during much of the remainder of the year, sufficient water trickles to supply several near-by dwellings.

Adjoining the village on the north and west are two small groves where a religious ceremonial is observed each month. Granaries for rice are scattered all about the outer fringe of dwellings, and in places they follow the ravines in among the buildings of the village. The old, broad Spanish trail runs close to the village on the south and east, as it passes in and out of the pocket through the gaps cut by the river. About the village at the east and northeast are some fifteen houses built in Spanish time, most of them now occupied by Ilocano men with Igorot or half-breed wives. There also were the Spanish Government buildings, reduced to a church, a convent, and another building used now as headquarters for the Government Constabulary.

The village, now 2,000 or 2,500 people, was probably at one time larger. There is a tradition common in both Bontoc and Samoki that in former years the ancestors of this latter village lived northeast of Bontoc toward the northern corner of the pocket...The Igorot is given to naming even small areas of the earth within his well-known habitat, and there are four areas in Bontoc village having distinct names. These names in no way refer to political or social divisions—they are not the “barrio” of the coast villages of the Islands, neither are they in any way like a “ward” in an American city, nor are they “additions” to an original part of the village—they are names of geographic areas over which the village was built or has spread. From south to north these areas are Afu, Mageo, Daowi, and Umfeg

RELATED ARTICLES:

BONTOC PEOPLE: LIFE. CULTURE, MARRIAGE factsanddetails.com

BONTOC RELIGION: GODS, ANITOS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

BONTOC PEOPLE IN THE EARLY 1900s: LIFE, LOVE, HOUSING, WEALTH factsanddetails.com

BONTOC HEAD HUNTING factsanddetails.com

MOUNTAIN PROVINCE IN CORDILLERA: MUMMIES, PINE FORESTS, BONTOC RICE TERRACES factsanddetails.com

RICE TERRACES OF NORTHERN LUZON factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RICE TERRACES OF BANAUE AND BATAD factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO RELIGION: GODS, RITUALS, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO SOCIETY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO IN 1910 AND PARTYING WITH AND PACIFYING THEM factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT LIFE: CUSTOMS, FOOD, DRINKS, TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Getting to Bontoc Country in 1905

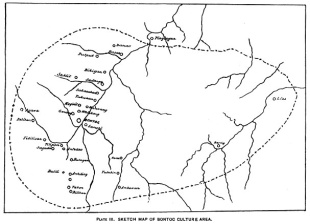

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The Spanish Bontoc area was estimated about 4,500 square kilometers...The area is well in the center of northern Luzon and is cut off by watersheds from other territory, except on the northeast. The most prominent of these watersheds is Polis Mountain, extending along the eastern and southern sides of the area; it is supposed to reach a height of over 7,000 feet. The western watershed is an undifferentiated range of the Cordillera Central. To the north stretches a large area of the present Province of Bontoc, though until 1903 most of that northern territory was embraced in the Province of Abra. The Province of Isabela lies to the east; Nueva Vizcaya and Lepanto border the area on the south, and Lepanto and Abra border it on the west. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The Bontoc culture area lies entirely in the mountains, and, with the exception of two villages, it is all drained northeastward into the Rio Grande de Cagayan by one river, the Rio Chico de Cagayan; but the Rio Sibbu, coursing more directly eastward, is a considerable stream.

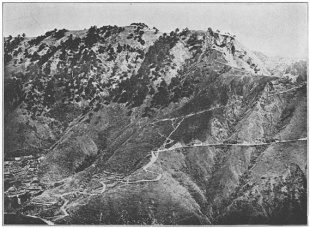

Today one main trail enters Bontoc Province. It was originally built by the Spaniards, and enters Bontoc village from the southwest, leading up from Cervantes in Lepanto Province. From Cervantes there are two trails to the coast. One passes southward through Baguio in Benguet Province and then stretches westward, terminating on the coast at San Fernando, in Union Province. The other, the one most commonly traveled to Bontoc, passes to the northwest, terminating on the coast at Candon, in the Province of Ilokos Sur. The main trail, entering Bontoc from Cervantes, passes through the village and extends to the northeast, quite closely following the trend of the Chico River.

The main trail is today passable for a horseman from the coast terminus to Tinglayan, three days beyond Bontoc village. Practically all other trails in the area are simply wild footpaths of the Igorot. Candon, the coast terminus of the main trail, lies in the coastal plain area about 4¼ miles from the sea. From the coast to the small village of Concepcion at the western base of the Cordillera Central is a half-day’s journey. The first half of the trail passes over flat land, with here and there small villages surrounded by rice sementeras. There are almost no forests. The latter half is through the coastal hill area, and the trail frequently passes through small forests; it crosses several rivers, dangerous to ford in the rainy season, and winds in and out among attractive hills bearing clumps of graceful, plume-like bamboo.

From Concepcion the trail leads up the mountain to Tilud Pass, historic since the insurrection because of the brave stand made there by the young, ill-fated General del Pilar. The climb to Tilud Pass, from either side of the mountain, is one of the longest and most tedious in northern Luzon. The trail frequently turns short on itself, so that the front and rear parts of a pack train are traveling face to face, and one end is not more than eight or ten rods above the other on the side of the mountain. The last view of the sea from the Candon-Bontoc trail is obtained at Tilud Pass. From Concepcion to Angaki, at the base of the mountain on the eastern side of the pass, the trail is about half a day long. From the pass it is a ceaseless drop down the steep mountain, but affords the most charming views of mountain scenery in northern Luzon. The shifting direction of the turning trail and the various altitudes of the traveler present constantly changing scenes—mountains and mountains ramble on before one. From Angaki to Cervantes the trail passes over deforested rolling mountain land, with safe drinking water in only one small spring. Many travelers who pass that part of the journey in the middle of the day complain loudly of the heat and thirst experienced there.

The first village beyond Cervantes is Cayan, the old Spanish capital of the district....Cayan is about four hours from Cervantes, and every foot of the trail is up the mountain. A short distance beyond Cayan the trail divides to rejoin only at the outskirts of Bontoc village; but the right-hand or “lower” trail is not often traveled by horsemen. Up and up the mountain one climbs from about 1,800 feet at Cervantes to about 6,000 feet among the pines, and then slowly descends, having crossed the boundary line between Lepanto and Bontoc subprovinces to the village of Bagnen—the last one before the Bontoc culture area is entered. It is customary to spend the night on the trail, as one goes into Bontoc, either at Bagnen or at Sagada, a village about two hours farther on.

Only along the top of the high mountain, before Bagnen is reached, does the trail pass through a forest—otherwise it is always climbing up or winding about the mountains deforested probably by fires.Practically all the immediate territory on the right hand of the trail between Bagnen and Sagada is occupied by the beautifully terraced rice sementeras of Balugan; the valley contains more than a thousand acres so cultivated. At Sagada lime rocks—some eroded into gigantic, massive forms, others into fantastic spires and domes—everywhere crop out from the grassy hills. Up and down the mountains the trail leads, passing another small pine forest near Ankiling and Titipan, about four hours from Bontoc, and then creeps on and at last through the terraced entrance way into the mountain pocket where Bontoc village lies, about 100 miles from the western coast, and, by Government aneroid barometer, about 2,800 feet above the sea.

Spanish Rule in the Bontoc Region

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The Spaniards and Ilocano in and about Bontoc Province say that it was about 1855 that the Spaniards first came to Bontoc. The time agrees very accurately with the time of the establishment of the district. From then until 1899 there was a Spanish garrison of 200 or 300 men stationed in Bontoc village. Christian Ilocano from the west coast of northern Luzon and the Christian Tagalog from Manila and vicinity were the soldiers. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The Spanish comandante of the “distrito,” the head of the political-military government, resided there, and there were also a few Spanish army officers and an army chaplain. A large garrison was quartered in Cervantes; there was a church in both Bontoc and Cervantes. In the district of Bontoc there was a Spanish post at Sagada, between the two capitals, Bontoc and Cervantes. Farther to the east was a post at Tukukan and Sakasakan, and farther east, at Basao, there was a post, a church, and a priest.

Most of the villages had Ilocano presidentes. The Igorot say that the Spaniards did little for them except to shoot them. There is yet a long, heavy wooden stock in Bontoc village in which the Igorot were imprisoned. Igorot women were made the mistresses of both officers and soldiers. Work, food, fuel, and lumber were not always paid for. All persons 18 or more years old were required to pay an annual tax of 50 cents or an equivalent value in rice. A day’s wage was only 5 cents, so each family was required to pay an equivalent of twenty days’ labor annually. In wild towns the principal men were told to bring in so many thousand bunches of palay—the unthreshed rice. If it was not all brought in, the soldiers frequently went for it, accompanied by Igorot warriors; they gathered up the rice, and sometimes burned the entire village. Apad, the principal man of Tinglayan, was confined six years in Spanish jails at Bontoc and Vigan because he repeatedly failed to compel his people to bring in the amount of palay assessed them.

The “tax” levied was scarcely in the nature of a modern tax; it was more the means taken by the Spaniard to secure his necessary food. In no other way was the political life and organization of the village affected. In the realm of religion and spirit belief the surface has scarcely been scratched. The only Igorot who became Christians were the wives of some of the Christian natives who came in with the Spaniard, mainly as soldiers. There are now eight or ten such women, wives of the resident Ilocanos of Bontoc village, but those whose husbands left the village have reverted to Igorot faith.

It is believed that no essential institution of the Igorot has been weakened or vitiated to any appreciable degree. No Igorot attended the school which the Spaniards had in Bontoc; today not ten Igorot of the village can make themselves understood in Spanish about the commonest things around them.

Bontoc Fighting and Headhunting in the Spanish Era

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: In the matter of war and head-hunting the effect of the Spaniard was to intensify the natural instinct of the Igorot in and about Bontoc village. Nineteen men in twenty of Bontoc and Samoki have taken a human head, and it has been seen under what conditions and influences some of those heads were taken. An Igorot, whose confidence I believe I have, an old man who represents the knowledge and wisdom of the people, told me recently that if the Americans wanted the people of Bontoc to go out against a village they would gladly go; and he added, suggestively, that when the Spaniards were there the old men had much better food than now, for many hogs were killed in the celebration of war expeditions—and the old men got the greater part of the meat. The Igorot is a natural head-hunter, and his training for the last sixty years seems to have done little more for him than whet this appetite.[Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The Spanish comandantes in charge of the province seem to have remained only about two years each. Saldero was the last one. Early in the eighties of the nineteenth century the comandante took his command to Barlig, a day east of Bontoc, to punish that town because it had killed people in Tulubin and Samoki; Barlig all but exterminated the command—only three men escaped to tell the tale. Mandicota, a Spanish officer, went from Manila with a battalion of 1,000 soldiers to erase Barlig from the map; he was also accompanied from Bontoc by 800 warriors from that vicinity. The Barlig people fled to the mountains, losing only seven men, whose heads the Bontoc Igorot cut off and brought home. Comandante Villameres is reported to have taken twenty soldiers and about 520 warriors of Bontoc and Samoki to punish Tukukan for killing a Samoki woman; the warriors returned with three heads. They say that in 1891 Comandante Alfaro took 40 soldiers and 1,000 warriors from the vicinity of Bontoc to Ankiling; sixty heads adorned the triumphant return of the warriors. In 1893 Nevas is said to have taken 100 soldiers and 500 warriors to Sadanga; they brought back one head. A few years later Saldero went to “clear up” rebellious Sagada with soldiers and Igorot warriors; Bontoc reports that the warriors returned with 100 heads.

The insurrectos appeared before Cervantes two or three months after Saldero’s bloody work in Sagada. The Spanish garrison fled before the insurrectos; the Spanish civilians went with them, taking their flocks and herds to Bontoc. A thousand pesos was the price offered by the Igorot of Sagada to the insurrectos for Saldero’s head when the Philippine soldiers passed through the village; but Saldero made good his escape from Bontoc, and left the country by boat from Vigan.

The Bontoc Igorot assisted the insurrectos in many ways when they first came. About 2 miles west of Bontoc is a Spanish rifle pit, and there the Spanish soldiers, now swelled to about 600 men, lay in wait for the insurrectos. There on two hilltops an historic sham battle occurred. The two forces were nearly a mile apart, and at that distance they exchanged rifle bullets three days. The Spaniards finally surrendered, on condition of safe escort to the coast. For fifty years they had conquered their enemy who were armed only with spear and ax; but the insurrectos were armed with guns. However, the really hard pressing came from the rear—there were still the ax and spear—and few soldiers from cuartel or trench who tried to bring food or water for the fighting men ever reported why they were delayed.

Health Issues Among the Bontoc in 1905

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The most serious permanent physical affliction the Bontoc Igorot suffers is blindness. Fully 2 percent of the people both of Bontoc and her sister village, Samoki, are blind; probably 2 percent more are partially so. Bontoc has one blind boy only 3 years old, but I know of no other blind children; and it is claimed that no babes are born blind. There is one woman in Bontoc approaching 20 years of age who is nearly blind, and whose mother and older sister are blind. Blindness is very common among the old people, and seems to come on with the general breaking down of the body. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

A few of the people say their blindness is due to the smoke in their dwellings. This doubtless has much to do with the infirmity, as their private and public buildings are very smoky much of the time, and when the nights are at all chilly a fire is built in their closed, low, and chimneyless sleeping rooms. There are many persons with inflamed and granulated eyelids whose vision is little or not at all impaired—a forerunner of blindness probably often caused by smoke.

The feet of adults who work in the water-filled rice paddies are dry, seamed, and cracked on the bottoms. These “rice-paddy feet” are often so sore that the person can not go on the trails for any considerable distance. An enlargement of the basal joint of the great toe, probably a bunion, is also comparatively common. It is not improbable that it is often caused by stone bruises, as such are of frequent occurrence; they are sometimes very serious, laying a person up ten days at a time.

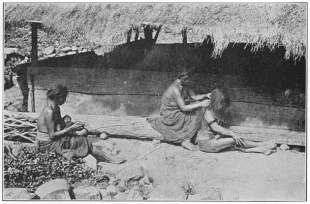

I believe not 5 percent of the people are without eruptions of the skin. It is practically impossible to find an adult whose body is not marked with shiny patches showing where large eruptions have been. Babes of one or two months do not appear to have skin diseases, but those of three and four are sometimes half covered with itching, discharging eruptions. Babes under a year old, such as are most carried on their mother’s backs, are especially subject to a mass of sores about the ankles; the skin disease is itch. I have seen babes of this age with sores an inch across and nearly an inch deep in their backs.

Relatively there are few large sores on the people such as boils and ulcers, but a person may have a dozen or half a hundred itching eruptions the size of a half pea scattered over his arms, legs, and trunk. From these he habitually squeezes the pus onto his thumb nail, and at once ignorantly cleans the nail on some other part of the body. The general prevalence of this itch is largely due to the gregarious life of the people—to the fact that the males lounge in public quarters, and all, except married men and women, sleep in these same quarters where the naked skin readily takes up virus left on the stone seats and sleeping boards by an infected companion. In Banawi, in the Quiangan culture area, a district having no public buildings, one can scarcely find a trace of skin eruption.

There are two adult people in Samoki village who are insane; one of them at least is supposed to be affected by Lumawig, the Igorot god, and is said, when he hallooes, as he does at times, to be calling to Lumawig. Bontoc village has a young woman and a girl of five or six years of age who are imbecile. Those four people are practically incapacitated from earning a living, and are cared for by their immediate relatives. There are two adult deaf and dumb men in Bontoc village, but both are industrious and self-supporting.

Disease and Remedies Among the Bontoc in 1905

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: By far the majority of deaths among them is due to what the Igorot calls fever—as they say, “impoos nan awak,” or “heat of the body”—but they class as “fever” half a dozen serious diseases, some almost always fatal. About thirty years ago cholera, visited the people, and fifty or more deaths resulted. Some twelve years ago kalagnas, an unidentified disease, destroyed a great number of people, probably half a hundred. Those afflicted were covered with small, itching festers, had attacks of nausea, and death resulted in about three days. One is surprised to find that sores from bruises do not generally heal quickly. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The men at times suffer with malaria. They go to the low west coast as cargadors or as primitive merchants, and they return to their mountain country enervated by the heat, their systems filled with impure water, and their blood teeming with mosquito-planted malaria. They get down with fever, lose their appetite, neither know the value of nor have the medicines of civilization, their minds are often poisoned with the superstitious belief that they will die—and they do die in from three days to two months. In February, 1903, three cargadors died within two weeks after returning from the coast.

Measles, chicken pox, typhus and typhoid fevers, and a disease resulting from eating new rice are undifferentiated by the Igorot—they are his “fever.” Measles and chicken pox are generally fatal to children. Igorot villages promptly and effectually quarantine against these diseases. When a settlement is afflicted with either of them it shuts its doors to all outsiders—even using force if necessary; but force is seldom demanded, as other villages at once forbid their people to enter the afflicted settlement. The ravages of typhus and typhoid fever may be imagined among a people who have no remedies for them. The diseased condition resulting each year from eating new rice has locally been called “rice cholera.” During the months of June, July, and August—the two harvest months of rice and the one following—considerable rice of the new crop is annually eaten. If rice has been stored in the palay houses until it is sweated it is in every way a healthful, nutritious food, but when eaten before it sweats it often produces diarrhea, usually leading to an acute bloody dysentery which is often followed by vomiting and a sudden collapse—as in Asiatic cholera.

In 1893 smallpox, ful-tâng, came to Bontoc with a Spanish soldier who was in the hospital from Quiangan. Some five or six adults and sixty or seventy children died. The ravage took half a dozen in a day, but the Igorot stamped out the plague by self-isolation. They talked the situation over, agreed on a plan, and were faithful to it. All the families not afflicted moved to the mountains; the others remained to minister or be ministered to, as the case might be. About thirty-five years ago smallpox wiped out a considerable settlement of Bontoc, called Lanao, situated nearer the river than are any dwellings at present.

The Igorot attempts no therapeutic remedies for fevers, cholera, beri-beri, rheumatism, consumption, diarrhea, syphilis, goiter, colds, or sore eyes. Some effort, therapeutic in its intent, is made to assist nature in overcoming a few of the simplest ailments of the body. For a cut, called “nafakag,” the fruit of a grass-like herb named la-layya is pounded to a paste, and then bound on the wound. Burns, malafûbchong, are covered over with a piece of bark from a tree called takumfao. Kay-yub, a vegetable root, is rubbed over the forehead in cases of headache. Boils, fuyui, and swellings, nayaman or kinmayyon, are treated with a poultice of a pounded herb called ok-ok-ongan. Millet burned to a charcoal, pulverized, and mixed with pig fat is used as a salve for the itch. An herb called a-kûm is pounded and used as a poultice on ulcers and sores. For toothache salt is mixed with a pounded herb named ot-ote(k and the mass put in or around the aching tooth. Leaves of the tree kayyam are steeped, and the decoction employed as a bath for persons with smallpox.

Food in the Bontoc Region

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: Rice is the staple food, and most families have sufficient for subsistence during the year. When rice is needed for food bunches of the unhusked rice, as tied up at the harvest, are brought and laid in the small pocket of the wooden mortar where they are threshed out of the fruit head. One or two mortarsful is thus threshed and put aside on a winnowing tray. When sufficient has been obtained the grain is put again in the mortar and pounded to remove the pellicle. Usually only sufficient rice is threshed and cleaned for the consumption of one or two days. When the pellicle has been pounded loose the grain is winnowed on a large round tray by a series of dexterous movements, removing all chaff and dirt with scarcely the loss of a kernel of good rice. Rice is cooked in water without salt. An earthern pot is half filled with the grain and is then filled to the brim with cold water. In about twenty minutes the rice is cooked, filling the vessel, and the water is all absorbed or evaporated. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

Cooked rice, ma-kan, is almost always eaten with the fingers, being crowded into the mouth with the back of the thumb. In Bontoc, Samoki, Titipan, Mayinit, and Ganang salt is either sprinkled on the rice after it is dished out or is tasted from the finger tips during the eating. In some villages, as at Tulubin, almost no salt is eaten at any time. When rice alone is eaten at a meal a family of five adults eats about ten Bontoc manojo of rice per day.

Beans are cooked in the form of a thick soup, but without salt. Beans and rice, each cooked separately, are frequently eaten together; such a dish is called “sib-fan.” Salt is eaten with sib-fan? by those villages which commonly consume salt. Maize is husked, silked, and then cooked on the cob. It is eaten from the cob, and no salt is used either in the cooking or eating.

Sweet potatoes are eaten raw a great deal about the village, the fields, and the trail. Before they are cooked they are pared and generally cut in pieces about 2 inches long; they are boiled without salt. They are eaten alone at many meals, but are relished best when eaten with rice. They are always eaten from the fingers. One dish, called “ke-leke,” consists of sweet potatoes, pared and sliced, and cooked and eaten with rice. This is a ceremonial dish, and is always prepared at the lis-lis ceremony and at a-su-fali-wis or sugar-making time. Sweet potatoes are always prepared immediately before being cooked, as they blacken very quickly after paring.

Millet is stored in the harvest bunches, and must be threshed before it is eaten. After being threshed in the wooden mortar the winnowed seeds are again returned to the mortar and crushed. This crushed grain is cooked as is rice and without salt. It is eaten also with the hands—“fingers” is too delicate a term.

Some other vegetable foods are also cooked and eaten by the Igorot. Among them is taro which, however, is seldom grown in the Bontoc area. Outside the area, both north and south, there are large fields of it cultivated for food. Several wild plants are also gathered, and the leaves cooked and eaten as the American eats “greens.”

Meat in the Bontoc Region

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The Bontoc Igorot also has preferences among his regular flesh foods. The chicken is prized most; next he favors pork; third, fish; fourth, carabao; and fifth, dog. Chicken, pork (except wild hog), and dog are never eaten except ceremonially. Fish and carabao are eaten on ceremonial occasions, but are also eaten at other times—merely as food. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

The interesting ceremonial killing, dressing, and eating of chickens is presented elsewhere, in the sections on “Death” and “Ceremonials.” It is unnecessary to repeat the information here, as the processes are everywhere the same, excepting that generally no part of the fowl, except the feathers, is unconsumed—head, feet, intestines, everything, is devoured.

The hog is ceremonially killed by cutting its throat, not by “sticking,” as is the American custom, but the neck is cut, half severing the head. At Ambuklao, on the Agno River in Benguet Province, I saw a hog ceremonially killed by having a round-pointed stick an inch in diameter pushed and twisted into it from the right side behind the foreleg, through and between the ribs, and into the heart. The animal bled internally, and, while it was being cut up by four men with much ceremony and show, the blood was scooped from the rib basin where it had gathered, and was mixed with the animal’s brains. The intestines were then emptied by drawing between thumb and fingers, and the blood and brain mixture poured into them from the stomach as a funnel. A string of blood-and-brain sausages resulted, when the intestines were cooked. The mouth of the Bontoc hog is held or tied shut until the animal is dead. The Benguet hog could be heard for fifteen minutes at least a quarter of a mile. After the Bontoc hog is killed it is singed, cut up, and all put in the large shallow iron boiler. When cooked it is cut into smaller pieces, which are passed around to those assembled at the ceremonial.

Fish are eaten both ceremonially and privately whenever they may be obtained. The small fish, the kacho, are in no way cleaned or dressed. Two or three times I saw them cooked and eaten ceremonially, and was told they are prepared the same way for private consumption. The fish, scarcely any over 2 inches in length, were strung on twisted green-grass strings about 6 inches in length. Several of these strings were tied together and placed in an olla of water. When cooked they were lifted out, the strings broken apart, and the fish stripped off into a wooden bowl. Salt was then liberally strewn over them. A large green leaf was brought as a plate for each person present, and the fish were divided again and again until each had an equal share.

However, the old men present received double share, and were served before the others. At one time a man was present with a nursing babe in his arms, and he was given two leaves, or two shares, though no one expected the babe could eat its share. After the fish food was passed to each, the broth was also liberally salted and then poured into several wooden bowls. At one fish feast platters of cooked rice and squash were also brought and set among the people. Handful after handful of solid food followed its predecessor rapidly to the always-crammed mouth. The fish was eaten as one might eat sparingly of a delicacy, and the broth was drunk now and then between mouthful. Two other fish are also eaten by the Igorot of the area, the liling, about 4 to 6 inches in length—also cooked and eaten without dressing—and the chalit, a large fish said to acquire the length of 4 feet.

The carabao is killed by spearing and, though also eaten simply as food, it is seldom killed except on ceremonial occasions, such as marriages, funerals, the building of a dwelling, and peace and war feasts whether actual events at the time or feasts in commemoration. The chief occasion for eating carabao merely as a food is when an animal is injured or ill at a time when no ceremonial event is at hand. The animal is then killed and eaten. All is eaten that can be masticated. The animal is neither skinned, singed, nor scraped. All is cut up and cooked together—hide, hair, hoofs, intestines, and head, excepting the horns. Carabao is generally not salted in cooking, and the use of salt in eating the flesh depends on the individual eater.

Sometimes large pieces of raw carabao meat are laid on high racks near the dwelling and “dried” in the sun. There are several such racks in Bontoc, and one can know a long distance from them whether they hold “dried” meat. If one village, in the area exceeds another in the strength and unpleasantness of its “dried” meat it is Mayinit, where on the occasion of a visit there a very small piece of meat jammed on a stick-like a “taffy stick”—and joyfully sucked by a 2-year-old babe successfully bombarded and depopulated our camp.

Various meats, called “it-tag,” as carabao and pork, are “preserved” by salting down in large bejuco-bound gourds, called “falay,” or in tightly covered ollas, called “tu-unan.” All villages in the area (except Ambawan, which has an unexplained taboo against eating carabao) thus store away meats, but Bitwagan, Sadanga, and Tukukan habitually salt large quantities in the falay. Meats are kept thus two or three years, though of course the odor is vile.

Bontoc Hunting in the 1900s

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The men go to the great rock, which is said to be a transformed anito, and there they build a fire, eat a meal, and have the ceremony called “mang-a-pui si ay-ya-wan,” freely, “fire-feast for wild carabaos.” The ceremony is as follows:

Ay-ya-wán ad Sa-kapa a-li-ká is-ná ma-ammung is-ná.

Ay-ya-wán ad O-ki-kí a-li-ká is-ná ma-ammung is-ná.

Fay-chami yai nan a-pui ya patay. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

This is an invitation addressed to the wild carabaos of the Sakapa and Okiki Mountains to come in closer to Bontoc. They are also asked to note that a fire-feast is made in their honor. The old men say that probably 500 wild carabaos have been killed by the men of the village. There is a tradition that Lumawig instructed the people to kill wild carabaos for marriage feasts, and all of those killed—of which there is memory or tradition—have been used in the marriage feasts of the rich. The wild carabao is extremely vicious, and is killed only when forty or fifty men combine and hunt it with spears. When wounded it charges any man in sight, and the hunter’s only safety is in a tree.

The method of hunting is simple. The herd is located, and as cautiously as possible the hunters conceal themselves behind the trees near the runway and throw their spears as the desired animal passes. No wild carabaos have been killed during the past two years, but I am told that the numbers killed three, four, six, seven, and eight years ago were, respectively, 5, 8, 7, 10, and 8.

Seven men in Bontoc have dogs trained to run deer and wild boar. One of the men, Aliwang, has a pack of five dogs; the others have one or two each. The hunting dogs are small and only moderately fleet, but they are said to have great courage and endurance. They hunt out of leash, and still-hunt until they start their prey, when they cry continually, thus directing the hunter to the runway or the place where the victim is at bay. Not more than one deer, ogsa, is killed annually, and they claim that deer were always very scarce in the area. A large net some 3½ feet high and often 50 feet long is commonly employed in northern Luzon and through the Archipelago for netting deer and hogs, but no such net is used in Bontoc. The dogs follow the deer, and the hunter spears it in the runway as it passes him or while held at bay.

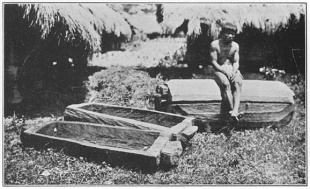

The wild hog, laman or fango, when hunted with dogs is a surly fighter and prefers to take its chances at bay; consequently it is more often killed then by the spearman than in the runway. The wild hog is also often caught in pitfalls dug in the runways or in its feeding grounds. The pitfall, fito, is from 3 to 4 feet across, about 4 feet deep, and is covered over with dry grass. In the forest feeding grounds of Polus Mountains, between the Bontoc culture area and the Banaue area to the south, these pitfalls are very abundant, there frequently being two or three within a space one rod square.

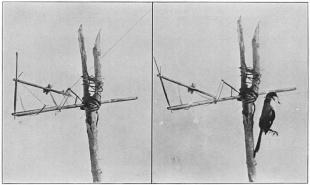

A deadfall, called “il-tib,” is built for hogs near the fields in the mountains. These deadfalls are quite common throughout the Bontoc area, and probably capture more hogs than the pitfall and the hunter combined. The hogs are partial to growing unhusked rice and sweet potato, and at night circle about a protecting fence anxious to take advantage of any chance opening. The Igorot leaves an opening in a low fence built especially for that purpose, as he does not commonly fence in the fields. The il-tib is built of two sections of heavy tree trunks, one imbedded in the earth, level with the ground, and the other the falling timber. As the hog enters the field, the weight of his body springs the trigger which is covered in the loose dirt before the opening, and the falling timber pins him fast against the lower timber firmly buried in the earth. From half a dozen to twenty wild hogs are annually killed by the people of the village. They are said to be as plentiful as formerly.

Bontoc Smoking and Fire-Making in 1905

Albert Ernest Jenks wrote: The Igorot of Bontoc area make pipes of wood, clay, and metal. All their pipes have small bores and bowls. In Benguet a wooden pipe is commonly made with a bowl an inch and a half in diameter; it has a large bore also. In Banaue I obtained a wooden pipe with a bowl 8¼ inches in circumference and 4 inches in height, but having a bore averaging only half an inch in diameter. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

In the western part of the area both men and women smoke, and some smoke almost constantly. Throughout the areas occupied by Christians children of 6 or 7 years smoke a great deal. I have repeatedly seen girls not over 6 years of age smoking rolls of tobacco, “cigars,” a foot long and more than an inch in diameter, but in Bontoc area small children do not smoke. In most of the area women do not smoke at all, and boys seldom smoke until they reach maturity.

In Bontoc the tobacco leaf for smoking is rolled up and pinched off in small sections an inch or so in length. These pieces are then wrapped in a larger section of leaf. When finished for the pipe the tobacco resembles a short stub of a cigar. Only half a dozen whiffs are generally taken at a smoke, and the pipe with its tobacco is then tucked under the edge of the pocket hat. Four pipes in five as they are seen sticking from a man’s hat show that the owners stopped smoking long before they exhausted their pipes. Page 133

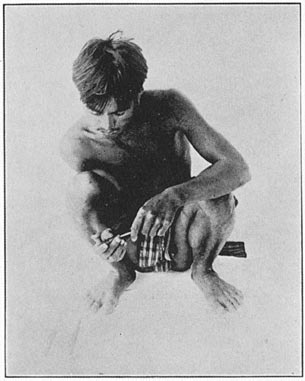

The oldest instrument for fire making used by the Bontoc Igorot is now seldom found. However, practically all boys of a dozen years know how to make and use it. It is called “co-lili,” and is a friction machine made of two pieces of dry bamboo. A 2-foot section of dead and dry bamboo is split lengthwise and in one piece a small area of the stringy tissue lining the tube is splintered and picked quite loose. Immediately over this, on the outside of the tube, a narrow groove is cut at right angles to it. This piece of bamboo becomes the stationary lower part of the fire machine. One edge of the other half of the original tube is sharpened like a chisel blade. This section is grasped in both hands, one at each end, and is at first slowly and heavily, afterwards more rapidly, drawn back and forth through the groove of the stationary bamboo, making a small conical pile of dry dust beneath the opening.

After a dozen strokes the sides of the groove and the edge of the friction piece burn brown, presently a smell of smoke is plain, and before three dozen strokes have been made smoke may be seen. Usually before one hundred strokes a larger volume of smoke tells that the dry dust constantly falling on the pile has grown more and more charred until finally a tiny friction-fired particle falls, carrying combustion to the already heated dust cone.

The machine is carefully raised, and, if the fire is permanently kindled, the pinch of smoldering dust is inserted in a wisp of dry grass or other easily inflammable material; in a minute or two flames burst forth, and the fire may be transferred where desired.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026