MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES

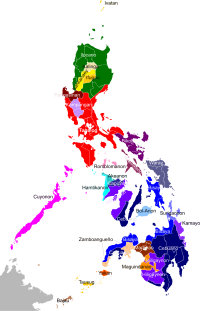

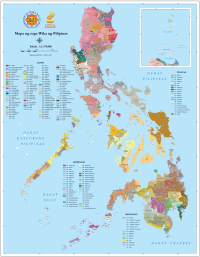

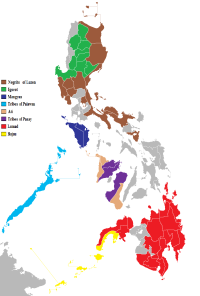

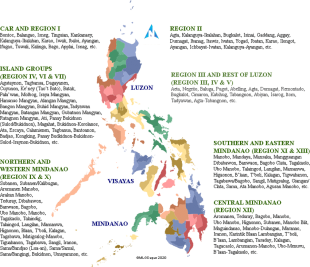

The Philippines has a diverse population with, by one count, over 134 ethnic groups, dominated by the Tagalog, Bisaya/Binisaya, Ilocano (9 percent), and Hiligaynon. The vast majority (approximately 85-87 percent) are lowland Christianized groups, while Indigenous Peoples and Muslim groups make up roughly 7.6 percent and 5.0 percent respectively.

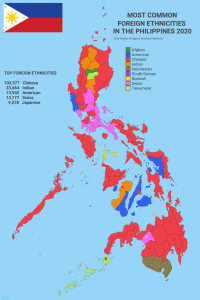

Based on the Philippines 2020 Census of Population and Housing, the main ethnic groups in the Philippines are:

Tagalog — 26.0 percent–28.1 percent

Bisaya/Binisaya (Visayan) — 14.3 percent–31.6 percent

Cebuano — Cebuano 8 percent–13.1 percent

Ilocano — 8 percent to 9 percent

Hiligaynon/Ilonggo — 7.5 percent–8 percent

Bikol/Bicol — 6.5 percent

Waray — 3.8 percent

Kapampangan — 3.0 percent

Other local ethnicities — 26.1 percent

Foreign ethnicity — 0.2 percent

Some of the differing percentages are attributed to mixed marriages and mixed ancestry

Ethnolinguistic groups collectively known as the Lowland Christians forms the majority ethnic group in the Philippines. About 142 groups are classified as non-Muslim indigenous people groups. There are about two dozen Muslim groups. The main ethnic and regional groups in the Philippines in 2000 according to the census that year were: 1) Tagalog (28.1 percent), 2) Cebuano (13.1 percent), 3) Ilocano (9 percent), 4) Bisaya/Binisaya (7.6 percent), 5) Hiligaynon Ilonggo (7.5 percent), 6) Bikol (6 percent) and 7) Waray (3.4 percent). To give you some idea how diverse and fragmented the Philippines is ethnically more than 100 other groups make up 25.3 percent of the population. [Source: 2000 census]

The dominant ethnic group both politically and culturally is the Tagalogs. There are social divisions between the Christian majority in the lowlands and the indigenous people in the highlands. The Christian lowlanders are found mostly on Luzon, Samar, Leyte, Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, Panay and Negros islands. Most Christian Filipinos on Mindanao are recent immigrants.

Ninety-five percent of the Philippines population is of Malay ancestry. The largest identifiable non-Malay group is the Chinese. According to one ethnic breakdown Christian Malays comprise 91.5 percent of the Philippines population; Muslim Malays: 4 percent; Chinese: 1.5 percent and Other: 3 percent.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

AETA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, LIFE, HUNTING, HEALTH factsanddetails.com

AGTA PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, FOOD factsanddetails.com

CHINESE IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

IGOROT — CORDILLERA PEOPLE OF NORTHERN LUZON — GROUPS AND HISTORY factsanddetails.com

IGOROT GROUPS — KANKANAEY, ISNEG, IBALOI — AND THEIR LIFE, CUSTOMS AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HEAD HUNTING TRIBES OF LUZON: PRACTICES, REASONS, WARS factsanddetails.com

IFUGAO: HISTORY, HEADHUNTING, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

Regional Ties in the Philippines

Identification with one’s group is regarded as strong and remains strong even when the groups go over seas. Tagalogs are regarded as proud, boastful and talkative. Pampangans are considered independent, self-centered and materialistic. Ilocanos are seen as hardworking, aggressive and worried about the future. And Visayans are seen as fun-loving, musical and courageous. Batangueños are known as the "salesmen of the Philippines."

Filipinos tend to have a strong sense of regional identity. People who come from the same province or who speak the same dialect often form close bonds and support one another, viewing themselves as “brothers” and “sisters.” In some situations, personal connections can matter as much as formal procedures, particularly when processing documents or seeking quick and favorable outcomes. [Source: Canadian Center for Intercultural Learning]

These regional, ethnic, and linguistic ties remain especially visible in Metro Manila, where neighborhoods and businesses may cluster around shared places of origin. While most Filipinos can speak Tagalog—the basis of the national language—many grow up speaking other Malay-based languages at home. Filipino (Tagalog) typically becomes the main language of instruction only at the secondary level, while English is usually used in higher education. Although the major Malay-based ethnic groups generally coexist without serious conflict, people often prefer to socialize and live near others from their own ethnic background.

Among Chinese Filipinos, many no longer speak Chinese dialects or have a strong awareness of their ancestral origins. Nevertheless, some resentment persists toward the economic success of Chinese-Filipino businesses, particularly regarding the community’s practice of financing its own enterprises and the high interest rates sometimes charged on informal or consumption loans.

Diversity of the Filipino People

In 1912, Cornélis De Witt Willcox wrote in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon”: “It is convenient to speak of the Filipino people, just as it is convenient to speak of the Danish people, or of the English; but whereas, when we say “Danish” or “English” we mean one definite thing that exists as such, when we say “Filipino” we should understand that the term stands for a relatively great number of very different things. For example, confining ourselves for the moment to the Christianized tribes, it may be asserted that the inhabitants of the great Cagayan Valley, the tobacco-growing country, are at least as different from those of the Visayas, the great middle group of Islands, as are the Italians from the Spanish. Precisely similar differences, increasing, roughly, with the difference of latitude, may be drawn almost at random between any other pairs of the elements constituting the Filipino population. The Ilokanos, to give only one more illustration, have almost nothing more, in common with the Bicols than the fact that they both probably come from the same original stock, just as the English and the Germans have the same ancestors. All these subdivisions speak different languages, and the vast majority do not speak Spanish at all. [Source:“The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” by Cornélis De Witt Willcox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S. Army, Professor United States Military Academy, 1912 ]

“But this is not all. The Filipino peoples are divided into two great classes, the Christian and the non-Christian. Now, these non-Christians number over a million, and are themselves broken up into many subdivisions, not only differing in language, customs, habits and traditions, but until very recently bitterly hostile to one another, and so low in the scale of political development that, unlike our own Indians, they have never risen to any conception of even tribal government or organization. Moreover, in Moroland, in the great island of Mindanao with its neighbors, the situation is further complicated by the fact that the dominant elements are Mohammedan. Over most of these non-Christians the Spaniards had not even the shadow of control.

“The appellation “Filipino people” is therefore wholly erroneous; more than that, it is even dangerously fallacious, in that its use blinds or tends to blind our own people to the real conditions existing in the Archipelago. It is correct to speak of the Filipino peoples, because this expression is, geographically, accurately descriptive; but it is absolutely misleading to speak of the Filipino people, because of the false political idea involved and conveyed by the use of the singular number. Similarly, there is no objection to the term “Filipino” or “Filipinos,” so long as we understand it to mean merely an inhabitant or the inhabitants of the Philippine Archipelago, more narrowly the Christianized inhabitant or inhabitants; but it is distinctly wrong to give to the term a political or national color. It may be remarked now that the divisions, both Christian and non-Christian, of which we have been speaking, determined as they are by natural conditions, are likely to survive for many generations to come.”

How Ethnic Minorities Are Classified in The Philippines

Many ethnic groups in The Philippines are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim minorities from the southernmost island group of Mindanao have been categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 groups are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous people groups. [Source: Wikipedia]

Roughly 86 to 87 percent of the Philippine population belongs to 19 ethnolinguistic groups that are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro. These populations are collectively known as the “lowland Christianized groups,” a term used to distinguish them from other ethnolinguistic communities. The largest of these groups—each numbering more than one million people—include the Ilocano, Pangasinense, Kapampangan, Tagalog, Bicolano, and the Visayan peoples, such as the Cebuano, Boholano, Hiligaynon (Ilonggo), and Waray. These lowland coastal populations, whether native or migrant, converted to Christianity during the Spanish colonial period, a process that contributed to their cultural unification and the adoption of many Western cultural elements over time.

About 142 Indigenous peoples in the Philippines are classified as neither Moro nor part of the lowland Christianized population. Some of these groups are often grouped together because they share the same geographic region, although such broad labels are not always accepted by the peoples themselves. For instance, the Indigenous communities of the Cordillera Mountains in northern Luzon are commonly referred to by the external name “Igorot,” or more recently as Cordilleran peoples. In Mindanao, the non-Moro Indigenous groups are collectively known as the Lumad, a self-chosen term adopted in 1986 to distinguish them from neighboring Moro and Visayan populations. Many of these smaller Indigenous communities remain socially marginalized and are often poorer than the national average.

Small Minorities of The Philippines

Numerous smaller ethnic groups inhabit the smaller islands and interiors of the larger islands of the Philippines. Among these are the Igorot of Luzon and the Bukidnon, Manobo, and Tiruray of Mindanao. At the southernmost reaches of the Philippine archipelago are communities of Sama-Bajua — “sea gypsies,” some of whom live on boats and depend almost entirely on the ocean for survival, moving with the seasons, the winds, and the tides.

There are approximately seventy to eighty language groups in The Philippines that separate people along tribal lines. The government protects approximately two million residents who are designated as cultural minority groups. Most of these ethnic groups live in the mountains of northern Luzon. [Source: Sally E. Baringer, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

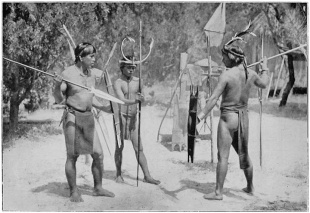

In northern Luzon you can find groups such as the Ifugao and the Kalinga live in small settlements and cultivate rice on terraces carved into steep mountain slopes. In more heavily forested regions, the Aeta continue to live as hunter-gatherers. In 1968, the Tasaday, were described as still living in the Stone Age but some scholars said the description was exaggerated or even a hoax. [Source: “Culture Shock!: Philippines” by Alfredo Roces and Grace Roces, Marshall Cavendish International, 2010]

Minority Etiquette when visiting the places they live: 1) Some fear photography. Don’t photograph anyone or anything without permission first. 2) Show respect towards religious objects and structures. Don’t touch anything or enter or walk through any religious structure unless you are sure it is okay. If in doubt ask. 3) Don’t interfere in rituals in any way. 4) Don’t enter a village house without permission or an invitation. 5) Error on the side of restraint when giving gifts. Gifts of medicine may undermine confidence in traditional medicines. Gift of clothes may encourage them to abandon their traditional clothes.

“Primitive” People of The Philippines

Beyond the lowland majority, the Philippines is home to numerous indigenous groups living in remote hilly and mountainous regions. These communities often speak languages unrelated to Malay and have distinct ethnic origins. In the Cordillera mountains of northern Luzon they are collectively known as Igorot; elsewhere in Luzon there are Aeta communities; in Mindoro, Mangyan groups occupy much of the uplands; and in parts of the Visayas, indigenous minorities have historically been referred to—often pejoratively—as “Negritos.” . [Source: Canadian Center for Intercultural Learning]

Karen Coates wrote in Archaeology magazine: Standard textbook lessons throughout the Philippines portray highland people in stereotypical terms as “primitive,” “warlike,” and “savage,” says Pia Arboleda of the University of Hawaii’s Filipino and Philippine Literature Program, who studies indigenous oral histories. She thinks mainstream Philippine society doesn’t take into account the diversity of the country, which is home to dozens of ethnic groups. “People don’t really like to accept that we are a multicultural, multiethnic community,” she says. “ [Source:Karen Coates, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

The following is a typical description of Luzon highlander in the early 20th century: Physically he is a clean-limbed, well-built, dark-brown man of medium stature, with no evidence of degeneracy. He belongs to that extensive stock of primitive people of which the Malay is the most commonly named. I do not believe he has received any of his characteristics, as a group, from either the Chinese or Japanese, though this theory has frequently been presented. The Bontoc man would be a savage if it were not that his geographic location compelled him to become an agriculturist; necessity drove him to this art of peace. In everyday life his actions are deliberate, but he is not lazy. He is remarkably industrious for a primitive man. In his agricultural labors he has strength, determination, and endurance. On the trail, as a cargador or burden bearer for Americans, he is patient and uncomplaining, and earns his wage in the sweat of his brow. His social life is lowly, and before marriage is most primitive; but a man has only one wife, to whom he is usually faithful. The social group is decidedly democratic; there are no slaves. The people are neither drunkards, gamblers, nor “sportsmen.” There is little “color” in the life of the Igorot; he is not very inventive and seems to have little imagination. His chief recreation—certainly his most-enjoyed and highly prized recreation—is head-hunting. But head-hunting is not the passion with him that it is with many Malay peoples. [Source: “Bontoc Igorot” by Albert Ernest Jenks, 1905]

His religion is at base the most primitive religion known—animism, or spirit belief—but he has somewhere grasped the idea of one god, and has made this belief in a crude way a part of his life. He is a very likable man, and there is little about his primitiveness that is repulsive. He is of a kindly disposition, is not servile, and is generally trustworthy. He has a strong sense of humor. He is decidedly friendly to the American, whose superiority he recognizes and whose methods he desires to learn. The boys in school are quick and bright, and their teacher pronounces them superior to Indian and Mexican children he has taught in Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico.

Upland Tribal Groups of the Philippines

There are more than 100 upland tribal groups and they constitute approximately 3 percent of the population. As lowland Filipinos, both Muslim and Christian, grew in numbers and expanded into the interiors of Luzon, Mindoro, Mindanao, and other islands, they isolated upland tribal communities in pockets. Over the centuries, these isolated tribes developed their own special identities. The folk art of these groups was, in a sense, the last remnant of an indigenous tradition that flourished everywhere before Islamic and Spanish contact. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Technically, the upland tribal groups were a blend in ethnic origin like other Filipinos, although they did not, as a rule, have as much contact with the outside world. They displayed great variety in social organization, cultural expression, and artistic skills that showed a high degree of creativity, usually employed to embellish utilitarian objects, such as bowls, baskets, clothing, weapons, and even spoons. Technologically, these groups ranged from the highly sophisticated Bontocs and Ifugaos, who engineered the extraordinary rice terraces, to more primitive groups. They also covered a wide spectrum in terms of their integration and acculturation with lowland Christian Filipinos. Some, like the Bukidnons of Mindanao, had intermarried with lowlanders for almost a century, whereas others, like the Kalingas on Luzon, remained more isolated from lowland influences. *

There are ten principal cultural groups living in the Cordillera Central of Luzon in 1990. The name Igorot, the Tagalog word for mountaineer, was often used with reference to all groups. At one time it was employed by lowland Filipinos in a pejorative sense, but in recent years it came to be used with pride by youths in the mountains as a positive expression of their separate ethnic identity vis-à-vis lowlanders. Of the ten groups, the Ifugaos of Ifugao Province, the Bontocs of Mountain and Kalinga-Apayao provinces, and the Kankanays and Ibalois of Benguet Province were all wet-rice farmers who worked the elaborate rice terraces they had constructed over the centuries. The Kankanays and Ibalois were the most influenced by Spanish and American colonialism and lowland Filipino culture because of the extensive gold mines in Benguet, the proximity of Baguio, good roads and schools, and a consumer industry in search of folk art. Other mountain peoples of Luzon were the Kalingas of KalingaApayao Province and the Tinguians of Abra Province, who employed both wet-rice and dry-rice growing techniques. The Isnegs of northern Kalinga-Apayao Province, the Gaddangs of the border between Kalinga-Apayao and Isabela provinces, and the Ilongots of Nueva Vizcaya Province all practiced shifting cultivation. Negritos completed the picture for Luzon. Although Negritos formerly dominated the highlands, by the early 1980s they were reduced to small groups living in widely scattered locations, primarily along the eastern ranges of the mountains. *

South of Luzon, upland tribal groups were concentrated on Mindanao, although there was an important population of mountain peoples with the generic name Mangyan living on Mindoro. Among the most important groups on Mindanao were the Manobos (a general name for many tribal groups in southern Bukidnon and Agusan del Sur provinces); the Bukidnons of Bukidnon Province; the Bagobos, Mandayas, Atas, and Mansakas, who inhabited mountains bordering the Davao Gulf; the Subanuns of upland areas in the Zamboanga provinces; the Mamanuas of the Agusan-Surigao border region; and the Bila-ans, Tirurays, and T-Bolis of the area of the Cotabato provinces. Tribal groups on Luzon were widely known for their carved wooden figures, baskets, and weaving; Mindanao tribes were renowned for their elaborate embroidery, appliqué, and bead work. *

The Office of Muslim Affairs and Cultural Communities succeeded in establishing a number of protected reservations for tribal groups. Residents were expected to speak their tribal language, dress in their traditional tribal clothing, live in houses constructed of natural materials using traditional architectural designs, and celebrate their traditional ceremonies of propitiation of spirits believed to be inhabiting their environment. They also were encouraged to reestablish their traditional authority structure in which, as in Moro society, tribal datu were the key figures. These men, chosen on the basis of their bravery and their ability to settle disputes, were usually, but not always, the sons of former datu. Often they were also the ones who remembered the ancient oral epics of their people. The datu sang these epics to reawaken in tribal youth an appreciation for the unique and semisacred history of the tribal group. *

Contact between primitive and modern groups usually resulted in weakening or destroying tribal culture without assimilating the tribal groups into modern society. It seemed doubtful that the shift of government policy from assimilation to cultural pluralism could reverse the process. James Eder, an anthropologist who has studied several Filipino tribes, maintains that even the protection of tribal land rights tends to lead to the abandonment of traditional culture because land security makes it easier for tribal members to adopt the economic practices of the larger society and facilitates marriage with outsiders. Government bureaus could not preserve tribes as social museum exhibits, but with the aid of various private organizations, they hoped to be able to help the tribes adapt to modern society without completely losing their ethnic identity. *

Chinese in the Philippines

The Philippines has a large population of people of Chinese ancestry. As in Thailand, Chinese in the Philippines have intermarried with Filipino and largely been assimilated into the population. Chinese make up between 1 percent and 1.5 percent of the population. Chinese language instruction has been restricted since 1973. Many young Filipino-Chinese consider themselves to be more Filipino than Chinese. Hokkein, the Southern Min dialect of Fujian, has traditionally been the primary dialect of many Overseas Chinese communities in Malaysia, Singapore Indonesia, and the Philippines whereas Teochew, the Southern Min dialect of Chaozhou, is the primary dialect of the Overseas Chinese communities in Thailand.

In 1990 the approximately 600,000 ethnic Chinese made up less than 1 percent of the population. Because Manila is close to Taiwan and the mainland of China, the Philippines has for centuries attracted both Chinese traders and semipermanent residents. The Chinese have been viewed as a source of cheap labor and of capital and business enterprise. Government policy toward the Chinese has been inconsistent. Spanish, American, and Filipino regimes alternately welcomed and restricted the entry and activities of the Chinese. Most early Chinese migrants were male, resulting in a sex ratio, at one time, as high as 113 to 1, although in the 1990s it was more nearly equal, reflecting a population based more on natural increase than on immigration. [Source: Library of Congress *]

There has been a good deal of intermarriage between the Chinese and lowland Christians, although the exact amount is impossible to determine. Although many prominent Filipinos, including José Rizal, President Corazon Aquino, and Cardinal Jaime Sin have mixed Chinese ancestry, intermarriage has not necessarily led to ethnic understanding. Mestizos, over a period of years, tended to deprecate their Chinese ancestry and to identify as Filipino. The Chinese tended to regard their culture as superior and sought to maintain it by establishing a separate school system in which about half the curriculum consisted of Chinese literature, history, and language. *

Intermarriage and changing governmental policies made it difficult to define who was Chinese. The popular usage of "Chinese" included Chinese aliens, both legal and illegal, as well as those of Chinese ancestry who had become citizens. "Ethnic Chinese" was another term often used but hard to define. Mestizos could be considered either Chinese or Filipino, depending on the group with which they associated to the greatest extent. *

Research indicates that Chinese were one of the least accepted ethnic groups. The common Filipino perception of the Chinese was of rich businessmen backed by Chinese cartels who stamped out competition from other groups. There was, however, a sizable Chinese working class in the Philippines, and there was a sharp gap between rich and poor Chinese. *

See Separate Article CHINESE IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Foreigners and Mixed People in The Philippines

Since the Spanish colonization of The Philippines, several communities of migrant heritage have become part of the population. These include Chinese Filipinos and Spanish Filipinos, both of whom intermarried with lowland Austronesian-speaking groups, giving rise to populations commonly referred to as Filipino mestizos. Together, these communities make up a significant share of the population and have played an especially prominent role in the country’s bourgeoisie and economic life. [Source: Wikipedia

These groups were also central to the formation of the Philippine nation, contributing to the rise of Filipino nationalism through the Ilustrado intelligentsia and playing important roles in the Philippine Revolution. In addition, the Philippines is home to other communities of migrant or mixed descent, including American Filipinos, Indian Filipinos, and Japanese Filipinos, who likewise form part of the country’s diverse social and cultural fabric.

In the 1980s, jets planes full of Japanese men arrived in Thailand and the Philippines on per-paid sex tours that included airfare, accommodations, transfers and a local girl waiting for them in their room. Many Japanese-Filipino children produced by marriages and liaisons between Japanese men and Filipinas have worked in Japan as "entertainers," a euphemism for prostitutes. A Manila-based woman's organizations estimates that there might be as many as 65,000 Japanese-Filipino children abandoned by their fathers in the Philippines.

Koreans are the biggest expatriate community in the Philippines. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 88,000 Koreans were living in the Philippines in 2012.The Philippine Department of Tourism said more than 1.16 million Koreans entered the country in 2013 Americans in the Philippines

In the late 1990s there were more than 100,000 Americans who have retired in the Philippines. Many are retired serviceman, who spend some time in the archipelago when they were in the service. In some towns they make up the majority of customers in some red light districts.

Dennis Rodman Meets His Father in the Philippines After 42 Years of Separation

Former NBA basketball Dennis Rodman's father, Philander Rodman Jr. , lives in the Philippines. In the early 2000s he lived with two wives and 15 of his 27 children and said he was shooting for 30 children. In 2012, Dennis Rodman had unexpectedly reunited in Manila with his estranged father, whom he had not seen for more than four decades. Philander had left Rodman’s mother nearly 50 years earlier and that the meeting occurred only because a touring team Rodman played for happened to be in the Philippines. [Source: Kelly Dwyer, Ball Don't Lie, Yahoo Sports, July 19, 2012]

According to the Associated Press, Philander Rodman Jr., who acknowledged fathering “29 children by 16 mothers,” said he was “happy and surprised” that his son agreed to meet him. Living in the Philippines for nearly 50 years, Philander said he wanted to explain that he had not intentionally abandoned his family, though the encounter was brief and limited to greetings and handshakes.

Dennis Rodman had previously expressed deep emotional distance from his father in his 1996 memoir Bad As I Want To Be. He wrote: “I never really knew my father… My father isn’t part of my life… Some man brought me into this world. That doesn’t mean I have a father; I don’t.” Rodman emphasized that he was raised by his mother and sisters and lacked a male role model until college.

Dwyer also highlighted that the AP mentioned Philander Rodman was running a restaurant in the Philippines called “Rodman’s Rainbow Obamaburger,” a detail Dwyer treated with heavy sarcasm. After the meeting, Rodman told the Associated Press, “I’ve been trying to meet him for years. And then last night, boom, I met him. I was really, really happy and very surprised.” He added, “It’s the beginning of something new.”

Jews in The Philippines

Marranos — Spanish and Portuguese Jews forced to convert to Catholicism in the 15th/16th centuries who secretly maintained Jewish beliefs and practices — are known to have lived in Manila among the earliest Spanish settlers. Because of this, they soon came under the attention of the Spanish Inquisition. The first public auto-da-fé in Manila was held in 1580, although it is unclear whether any Jews were among the seven people accused at that time. [Source: Walter Zanger and Ernest E. Simke, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In 1593, two Marrano brothers, Jorge and Domingo Rodriguez, long-time residents of Manila, were tried at an auto-da-fé in Mexico City. The case was heard there because the Inquisition did not maintain an independent tribunal in the Philippines. Both brothers were sentenced to imprisonment. By the end of the seventeenth century, at least eight Marranos from the Philippines are known to have been tried by the Inquisition.

Large-scale Jewish immigration to the Philippines did not begin until the late nineteenth century. The first documented arrivals were the Levy brothers from Alsace, who came to Manila in the early 1870s to establish a jewelry business and later brought additional workers to staff their shop. They were followed by Jews from Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt, as well as families from Russia and Central Europe, some arriving via Harbin and Shanghai. In the early twentieth century, Jews from the United States also settled in the Philippines.

By the early 1930s, the Jewish population in the Philippines had reached about 500. In 1922, the Manila Jewish congregation was formally organized. Soon afterward, land was purchased for a synagogue and cemetery, and in 1924 Temple Emil was built, named after its benefactor Emil Bachrach.

Through the efforts of the local Jewish community, the support of Philippine Commonwealth president Manuel Quezon—who donated land for refugee settlement—the encouragement of U.S. authorities, and the lack of other safe options, the Philippines became a refuge for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. By the end of World War II, the Jewish population had grown to more than 2,500. Among the refugees were Rabbi Joseph Schwartz and a cantor who served the community.

The final months of 1944 and early 1945 were disastrous. The Japanese military had used the synagogue and its adjacent hall as an ammunition depot, and both buildings were destroyed during the fighting. About ten percent of the Jewish population died as a result of Japanese atrocities or American shelling during the liberation of Manila.

After the war, the Jewish community reorganized and rebuilt its synagogue. By 1968, the population had declined to about 250, roughly a quarter of whom were Sephardic Jews. In 2005, the community still numbered around 250 members, mostly Americans and Israelis, and maintained a rabbi, a mikveh, and a Sunday school.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026