MORO GROUPS OF MINDANAO

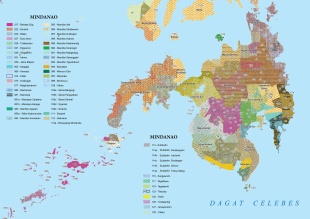

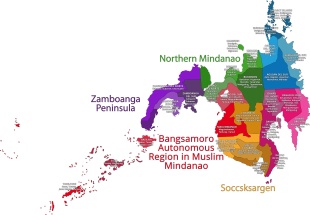

Mindanao, Philippines, is highly diverse, featuring three main cultural groupings: A) the 18+ indigenous Lumad tribes such as the Manobo, Bagobo and Tiboli; B) the 13+ Moro (Muslim) ethno-linguistic groups such as the Maranao, Maguindanao and Tausug), and C) significant Christian settler populations primarily of Visayan descent. Lumad, meaning "native," inhabit the interior highlands, while Moro groups are concentrated in western Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.

The settler and migrant populations — mainly Christians from Visayas (islands between Luzon and Mindanao — mostly arrived in the 20th-century as part of government-sponsored migration programs. They are most heavily concentrated in coastal regions and cities. These communities are distinguished by their diverse languages, traditions, and ancestral domains. In the early 2000s, around 25.8 percent of the population in Mindanao classified themselves as Cebuanos. Other ethnic groups included Bisaya/Binisaya (18.4 percent), Hiligaynon/Ilonggo (8.2 percent), Maguindanaon (5.5 percent), and Maranao (5.4 percent). The remaining 36.6 percent belonged to other ethnic groups.

The Muslim ethnic groups of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan are collectively referred to as the Moro people, a broad category that includes some indigenous people groups and some non-Indigenous people groups. With a population of over 5 million people, they comprise about 5 percent of the country's total population. Traditionally-Muslim minorities from Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are indigenous peoples or not. [Source: Wikipedia]

The 13 recognized Moro groups include the Maguindanao, Maranao, Tausug, Yakan, Sama (or Samal), Badjao (Sama Dilaut), Iranun, Sangil, Jama Mapun, Kalagan, Palawanon, Molbog, and Kalibugan.

The Iranun, Maranao and Maguindanaon all speak Danao languages. After Shariff Kabungsuwan — a key figure in introducing Islam to Mindanao and the Philippines — arrived in Mindanao from Johor in present-day Malaysia in the 15th or 16th century, he established a sultanate known as the Sultanate of Maguindanao in an Iranun kingdom known as T'bok. Throughout the 16th century, the Iranuns and Samal mercenaries formed the core of the sultanate. The sultanate traces its ancestry to Iranun roots. For several centuries, the Iranuns in the Philippines were part of the sultanate. The Maguindanao Sultanate's seat was previously located in Lamitan (now part of Picong, Lanao del Sur) and T'bok, both of which were Iranun strongholds.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

TASADAY OF THE PHILIPPINES: STONE-AGE TRIBE, A HOAX, OR SOMEWHERE BETWEEN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE CENTRAL PHILIPPINES ISLANDS: VISAYANS, CEBUANO, WARAY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

Different Moro Groups

The Iranun live inland from Polloc Harbor on Moro Gulf on Mindanao. Also known as the Ilanon, Ilano, Ilanum, Ilanun, Illanun, Iranon, Lanon, they are closely related to the Maguindanao and have a history of being pirates. In the old days Ilanaon boats rowed by slaved were notorious for staging raids in Borneo and Malaysia. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Iranun numbers 282,000 in early 2020s and 99.9 percent of them are Muslims. See Maguindanao [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993). Joshua Project]

The Kalagan is a group that lives in the uplands inland from the western coast of the Davao Gulf on Mindanao. Also known as the Calagan, Kagan, Karagan, Laoc, Saka and Tagakaolo, they are closely related to the Maguindanao and have converted to Islam relatively recently and retain many of their traditional beliefs. Some and slash and burn agriculturalists. Other are laborers and fishermen. See Maguindanao.

The Kalibugan is a group that lives in villages on the west coast of Mindanao. Kalibugan (Kolibugan) means mixed breed. It refers to Subanun who have intermarried with Tausaug and Samal. See Subanen Under Lumad

The Sangir is a group that lives in the Sanihe and Taluad islands between southern Mindanao and northern Sulawesi. Also known as the Sangirezen and Talaoerezen, they are also found in Mindanao and Indonesia. Most are Christians although some are Muslims. Most have been assimilated into the national culture. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

Maguindanao

The Maguindanao live in south-central Mindanao. Also known as the Magindanao, Maguindanaon, Maguindanau and Magindanaw, they are the largest group of Muslim Filipinos. They speak a language that is in the same group as most other Philippines languages, including Tagalog, and are believed to have converted to Islam around the 15th and 16th centuries. According to legend, they were converted by a Malay prince from Johor named Sarip Kabungsuwan, who was a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed and married a local who was born miraculously from a stalk of bamboo. "Maguindanao" means "people of the flood plain." The total Maguindanao population according to the 2020 Philippines census was 2,021,099. [Source: Wikipedia, James C. Stewart,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Maguindanao have traditionally lived in villages along waterways and the coast, and moved around by boat and dominated trade between other groups in the area where they live. Large settlements, towns and cities grew up at major trading centers. Chiefs known as datus traditionally lived in large communal houses while ordinary villagers lived in single-family dwellings made of homes wood, bamboo and “nipa” thatch. This patterns was disrupted after the arrival of American administration and the building of roads. Then, communities sprang up on roads rather that waterways.

The datu held a position of special respect and directed many community affairs, presiding over social and religious events. Deference extended to his wife or wives and other high-ranking relatives, who often lived nearby. Larger central communities under a datu were typically surrounded by smaller satellite villages composed of loosely related kin groups. Above the datus were the sultans, the highest political leaders in the past. At any given time, two to four sultans ruled different parts of Cotabato, though only some exercised significant influence beyond their immediate territories. A sultan was chosen by a council of datus and depended on their support to maintain authority. Today, the title of sultan is largely honorific, but datus still retain local influence. Intermarriage among datu families has sustained broad alliance networks that remain politically significant, even at the national level.

The south-central region of Mindanao, home to most of the Maguindanao, lies between 6° and 8° north latitude and 124° and 126° east longitude. Historically, this area was known as Cotabato, a name derived from the Malay term meaning “stone fort,” referring to a fortress that once stood at the mouth of the Pulangi River—the principal route into the interior of the Cotabato Valley. The valley is almost entirely encircled by mountains, opening only toward the west. The Pulangi River, now more commonly called the Mindanao River, is formed by several tributaries that descend from the surrounding highlands. These waterways wind across the valley floor before joining together and flowing into the Moro Gulf along the western coast. A large portion of the valley consists of extensive marshland. During seasons of heavy rainfall and flooding, the area can resemble a broad, shallow lake. Rainfall is plentiful and relatively consistent throughout the year, with the heaviest rains typically occurring between May and October.

The Maguindanao language is related to many other Philippine languages, including Tagalog. It is most closely related to the Maranao language, which is spoken by a Muslim group of the same name living just north of Cotabato. The Maguindanao people have a strong cultural affinity with this group. Maguindanao society has traditionally been hierarchically organized with datus and their families at the top and status defined by one’s “maratabat” ranking, often determined by a claimed descendent from Sarip Kabungsuwan. One’s position in this system determines whom you can marry and what opportunities are open to them. Datu, and the sultans above them, make many important decisions and are treated with great respect. Households are usually comprised of extended families with uncles, aunts and grandparents and other relatives participating in the childrearing process.

Maguindanao History and Religion

The Maguindanao are among the lowland Filipino groups who migrated from mainland Southeast Asia thousands of years ago and were firmly established in Cotabato by around 1500. Islam spread to the region through Muslim missionaries, most notably the legendary Sarip Kabungsuwan, a prince from Johor who is said to have peacefully converted local communities and founded ruling lineages through marriage alliances. His descendants reportedly became the elite families of the Maguindanao and neighboring Maranao. [Source: James C. Stewart,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Spanish contact in the 16th century led to centuries of conflict. Labeling Muslim Filipinos as “Moros,” the Spaniards waged the long Moro Wars against the Maguindanao and their allies, who were never fully conquered. After the United States took control in 1898, American forces subdued major resistance by 1905. American and later Philippine policies encouraged Christian migration to Mindanao, and after World War II large-scale settlement in Cotabato led to Muslims becoming minorities in many areas. Land disputes and ethnic tensions erupted into armed conflict in 1970, escalating into civil war and fueling movements for greater Muslim autonomy in the south.

Historically, the fertile Cotabato Valley was sparsely populated, with perhaps 100,000 Maguindanao by the early 20th century. By 1948, about 155,000 Muslims—mostly Maguindanao—were recorded in Cotabato. Census and linguistic data from 1980 suggest the population had grown to well over 500,000 by that time, and likely significantly higher, reflecting substantial demographic expansion despite political turmoil.

Maguindanao primarily practice a form of folk Islam in which Islamic beliefs and rituals coexist with older animistic traditions. While Islamic observance has gradually become more orthodox, many people continue to believe in environmental spirits, magic, sorcery, and supernatural beings. Even Sarip Kabungsuwan, credited with introducing Islam to the region, is portrayed in tradition as possessing magical powers.

Formal religious life is led by Muslim figures such as the imam and pandita, who oversee rituals and teach boys to read and memorize the Quran. Alongside them are less visible ritual specialists who address indigenous spiritual concerns, such as performing rites to ensure good harvests and appease nature spirits. Major Islamic observances, especially Ramadan fasting, are widely practiced. Ceremonies related to birth, marriage, and death often blend Islamic teachings with indigenous rituals, reflecting the continued integration of older beliefs within Maguindanao religious practice.

Maguindanao Life

The Maguindanao have traditionally raised a variety of crops, trapped fish and obtained wild woods and other materials from marshes. Wet rice is grown in the lowland and dry rice in the highlands. Yams and sweet potatoes are another important food crop. Coconut are a food source and major cash crop. Coconut milk is widely used in cooking. Goats, freshwater fish and saltwater fish are the main protein sources. Water buffalo are slaughtered when they are old for meat. [Source: James C. Stewart,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ]

Even today Maguindanao produce most of their own food. The Maguindanao have traditionally been traders and subsistence farmers and didn’t produce many goods other than some mats and crafts for sale. In the old days, salt, metal goods, Chinese pottery, cloth and beads were major trade items. Land was communally owned. All this has changed in recent years. Trade is largely gone and it hasn’t been replaced by modern economy.

Muslim customs shape many aspects of Maguindanao life. Polygamy is allowed but is generally only practiced by men wealthy to afford to be able to care for multiple wives. Bride prices are paid and divorces are relatively easy yo obtain. Children memorize the Koran. Marriage rules reflect both exogamy (in the group) and endogamy (outside the group) . Individuals raised in the same extended household or village are considered too closely related to marry, creating local exogamy regardless of actual blood ties. At the same time, there is a preference for marriage among related families—especially second cousins—resulting in a tendency toward kindred endogamy. First-cousin marriages are rare and traditionally prohibited.

Although the Maguindanao trace descent through both maternal and paternal lines, kinship is strongly influenced by social rank, or maratabat. High status depends on claimed descent from Sarip Kabungsuwan, and elite families maintain detailed genealogies to support these claims. From these high-ranking lineages come the datus and sultans, who traditionally held central political authority. The highest-ranking members of this society tend to be removed from manual labor. Among the rest, the division of labor between men and women is not very pronounced. Men plow, harrow, and perform other heavy farming tasks. Women perform most domestic tasks, often with the help of older children. Nearly all able-bodied adults and young people participate in tasks such as planting, weeding, harvesting, and threshing. ~

Bloods feud have been a feature of Maguindanao life. Triggered by a death that a family feels has to be avenged, the can go a long time and result in numerous reprisal killings. Sometimes the feud can be averted in the early stages by the payment of a cash settlement from the killer’s family to the victim’s family, based on the rank of the victim, or through the capture of the killer by authorities and meting out of harsh penalties under jurisdiction of a datu.

Maranao

The Maranao live mainly around Kale Lanao in northwest Mindanao. They are the second largest Muslim group after the Maguindanao. They have traditionally been an inland people which makes them different from other Muslim groups which has traditionally been coastal people. They converted to Islam relatively late but have been leaders in the resistance movement against the Spanish, Americans, Japanese and Philippine government. The total population of Maranao according to the 2020 Philippines census is 1,800,130, up from about 840,000 in 1983. [Source: Jay DiMaggio, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Maranao speak Maranao, an Austronesian language, and are closely related to the Iranun (also known as Iranon, Illanun, or Ilanon). Kinship is bilateral, on both the male and female lines, allowing individuals to claim ties to multiple villages, which are defined more by shared descent than by territory. Traditionally, Maranao society has been divided into two strata: The mapiyatao (pure) and the kasilidan (mixed blood), which is further subdivided into the following categories: sarowang (non-Maranao), balbal (beast), dagamot (sorcerer/sorceress), and bisaya (slave). Mapiyatao natives are entitled to ascend to thrones through a pure royal bloodline. In contrast, the kasilidan are suspected of having a mixed bloodline. However, due to changes over time and improving economic conditions, these social strata are beginning to decline. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Maranao have traditionally been fishermen and farmers and lived in villages made up of a few households but the households have often been large with several families living together in a large unpartitioned house with people sleeping along the walls and the rear of the dwelling serving as a communal kitchen. Fertile soil in their homeland has meant food has never been a problem and surpluses have been traded along with cloth, mats, wood carvings and gold and silver jewelry. Rank is determined more on the basis of skill and merit than hereditary status.

Maranao Islam has a strong Sufi influence and incorporates many pre-Islamic beliefs in spirits, particularly those related to the agricultural cycle. Sufism is manifested in chants and rituals. Social rank depends on personal abilities—such as skill in oratory, Quranic recitation, or legal knowledge—as well as recognized leadership qualities. Highlights of Maranao culture include: 1) the torogan, the traditional royal house, whose elaborate architecture is considered among the most aesthetically refined in the Philippines; 2) kirim, a pre-Hispanic writing system derived from Arabic script, consisting of 19 consonants and 7 vowels; 3) singkil, a traditional dance inspired by an episode from the Darangen epic; 4) okir, the distinctive flowing designs seen in Maranao wood and metal carvings; 5) kaplagod, or horse racing; 6) the tabo, a drum used in mosques to summon worshippers to prayer; and 7) the kulintang, a gong-based musical ensemble central to Maranao ceremonial life. [Source: Wikipedia]

Darangen Epic of the Maranao People of Lake Lanao

The Darangen is an ancient epic song that encompasses a wealth of knowledge about the Maranao people who live in the Lake Lanao region of Mindanao.Comprising 17 cycles and a total of 72,000 lines, the Darangen celebrates episodes from Maranao history and the tribulations of mythical heroes. In addition to offering compelling narrative content, the epic explores the underlying themes of life and death, courtship, politics, love and aesthetics through symbol, metaphor, irony and satire. The Darangen also encodes customary law, standards of social and ethical behaviour, notions of aesthetic beauty, and social values specific to the Maranao. To this day, elders refer to this time-honored text in the administration of customary law. [Source: UNESCO]

Meaning literally “to narrate in song” in the Maranao language, the Darangen existed before the arrival of Islam in the Philippines in the fourteenth century. Being part of a wider epic culture that is connected to early Sanskrit practices and extends through most of Mindanao, it offers insight into pre-Islamic cultural traditions of the Maranao people.

Though the Darangen has been largely transmitted orally, parts of the epic have been recorded in manuscripts using an ancient Arabic-based writing system. Being cherished as heirlooms by certain Maranao families, these manuscripts are highly valued for their antiquity and prestige value. Specialised performers of either sex sing the Darangen during wedding celebrations that typically last several nights. Performers must possess a prodigious memory, improvisational skills, poetic imagination, knowledge of customary law and genealogy, a flawless and elegant vocal technique, and the ability to engage an audience during long hours of performance. Music and dance sometimes accompany the chanting.

Nowadays, the Darangen is infrequently performed owing in part to its rich vocabulary and archaic linguistic forms that can only be understood by practitioners, elders and scholars. Indeed, the growing tendency to embrace mainstream Filipino lifestyles represents a serious threat to the survival of this ancient epic.

Tausug

The Tausug is the dominant group in the Sulu Archipelago. Also known as the Joloanos, Jolo Moros, Suluk, Suluk Moros, Sulus and Taw Sug, they are a Muslim seafaring people that once presided over an empire that stretched from the southern Philippines to Borneo. The are the most numerous on the Sulu island of Jolo and are present in large numbers on other Sulu islands and in southern Mindanao. They have traditionally occupied parts of the coastline suitable for agriculture, leaving the low islands and coastlines to the Sama-Bajua (Samal). The Tausug are fairly conservative. Children attend Koranic school and study the Koran with tutors. Even so beliefs in spirits and superstitions endure. Children wear amulets for protection and sick people seek help from folk healers. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Tausug means "people of the current" (tau, "people"; sug, "sea current"). Their total population is around 1.9–2.2 million, with about 1,615,823 in the Philippines, 209,000–500,000 in Malaysia and 12,000 in Indonesia. The Tausug appear to have come to the Sulu islands from southern Mindanao and converted to Islam possibly as early as the 11th century. Their sultan was at the peak of his power in the 18th and early 19th century and grew rich largely from trading slaves, many who were Christian Filipinos. The slave trade was ended by the Americans who took over Jolo town in 1899 but were not able to control the island until 1913, and even then only nominally so. Jolo today is at the forefront of the Islamic separatist movement.

The Tausug are primarily agriculturist who grow a wide variety of starch crops, vegetables and fruit. They live in thatch-roof, timber- or bamboo walled houses set close to family fields. Households or clusters of two or three households make up many communities. Large villages are organized around a core kin group. Boundaries of villages tend to be ill defined and this has led to feuds, which can be quite nasty, involving battles with a 100 people on each side. Coconuts and smuggling are major economic activities. In the past coastal raiding and piracy were common forms of employment.

See Separate Article: ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

Yakan

The Yakan is a group that lives on the island of Basilan south of Mindanao. They have traditionally lived on the interior of the island, particularly in the east central and southwestern parts, while Samal ad Tausug lived on the coasts. There are around 100,000 Yakan and they make up half the population of Basilan.

The Yakan are believed to be the original inhabitants of Basilan. The Samal and Tasuag arrived later from the Sulu islands and Christian Filipinos came from the north. During the 1970s the Yakans suffered badly when rebels took over much of the island and many Yakan were evacuated. They continue to suffer as a result of Islamic insurgents basing themselves there.

The Yakan are Muslims and the language they speak is similar to that of the Samal. They live in bamboo-wall and thatch -roof houses set up in middle of fields. The houses are often widely scattered to the point it is difficult to figure out where one village ends and another begins. They are primarily farmers who raise dry rice and a variety of vegetables and fruit and keep water buffalo as plow animals. Coconuts are an important cash crop.

See Separate Article: ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

Sama-Bajau Sea People

The term Sama-Bajau is used to describe a diverse group of Sama-Bajau-speaking people who are found in a large maritime area with many islands that stretch from central Philippines to the eastern coast of Borneo and from Sulawesi to Roti in eastern Indonesia. The Sama-Bajau people usually call themselves the Sama or Samah (formally A'a Sama, "Sama people") and have traditionally been known by outsiders as Bajau (also spelled Badjao, Bajaw, Badjau, Badjaw, Bajo or Bayao). They have also been Sea Gypsies, Sea Nomads and Samal as well as Sama Moro and Turijene in the Philippines, Luwa’an, Pala’au, Sama Dilaut and Turijene in Indonesia, and the Bajau Laut in Malaysia. Some of these names refer to Sama-Bajua subgroups. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Most Sama-Bajau are Muslims. In the Philippines, they are grouped with the Moro people, who have similar religious beliefs. For most of their history, the Sama-Bajau have been nomadic seafaring people who live off the sea through trade and subsistence fishing. They have traditionally stayed close to shore with houses on stilts and traveled, and sometimes lived in, handmade boats lepa. Sama-Bajau are the dominant ethnic group in Tawi-Tawi islands and are generally associated with the Sulu islands, the southernmost islands of the Philippines. They are also found in the coastal areas of Mindanao and other islands in the southern Philippines, as well as in northern and eastern Borneo, Sulawesi, and throughout the eastern Indonesian islands.

Sama-Bajau speakers are probably the most widely dispersed indigenous ethnolinguistic group in Southeast Asia. Their settlements are scattered throughout the central Philippines, the Sulu Archipelago, the eastern coast of Borneo, Palawan, western Sabah (Malaysia), and coastal Sulawesi. They also have small enclaves in Zambales and northern Mindanao. In the Philippines, most Sama speakers are referred to as "Samal," a Tausug term also used by Christian Filipinos, with the exceptions of Yakan, Abak, and Jama Mapun. In Indonesia and Malaysia, related Sama-speaking groups are known as "Bajau," a term of apparent Malay origin. In the Philippines, however, the term "Bajau" is more narrowly reserved for boat-nomadic or formerly nomadic groups referred to elsewhere as "Bajau Laut" or "Orang Laut."

RELATED ARTICLES:

SAMA-BAJUA SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJUA LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Molbog

The Molbog—also known as Malebugan or Malebuganon—are the dominant indigenous group in the southernmost municipalities of Palawan, particularly Balabac and Bataraza, as well as parts of Brooke’s Point and Rizal. Smaller Molbog communities are also found in Mapun (Tawi-Tawi) and along the northern coast of Borneo. They are the only indigenous group in Palawan whose population is overwhelmingly Muslim, with estimates placing their number at around 20,000–24,000 people, more than 99 percent of whom adhere to Islam. [Source: Wikipedia, Ethnic Groups Philippines]

Balabac Island has long been regarded as the Molbog homeland, predating Spanish colonization. Some accounts describe them as having ancestral links to northern Borneo, while linguistic and historical evidence suggests they were originally an indigenous Palawan subgroup who later converted to Islam. Through sustained contact and intermarriage with Tausug and Samal groups under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate, the Molbog developed a distinct identity. Villages were historically led by religious authorities under Sulu datus, and today the Molbog language reflects Tausug and Jama Mapun influences. As practicing Muslims, they observe the Five Pillars of Islam and incorporate Arabic chants into religious life.

The name “Molbog” is believed to derive from malubog, meaning “murky or turbid water,” referring to the muddy coastal waters of Balabac caused by inland flooding. Historically, Palawan served as a trading hub between the Philippines and Brunei, with Tausug merchants stopping to resupply. The Molbog engaged in fishing, subsistence farming, and barter trade with nearby Sulu communities and markets in Sabah, Malaysia. Coconut cultivation remains central to their economy, with copra as a key product.

See Separate Article: ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026