VISAYANS

Visayans are the second largest ethnic group in Philippines. Also known as Bisaya, Bisayan, and Pintado, they are regarded as a metaethnicity and are native to the Visayas — islands south of Luzon — and a significant portion of Mindanao. The Spanish used to call them the Pintados because they painted their bodies. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

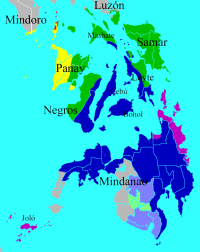

Visayan is a general term used to describe the people who live on the central islands of the Philippines around the Visayan Sea. The group is composed of numerous distinct ethnic groups including the Cebuano, Boholano, Eskaya, Ilonggo, Waray, Surigaonon, Karay-a, Capiznon, Masbateño, Cuyunon, Aklanon, Romblomanon and Butuanon. When taken as a single group, they number around 45.5 million and make up 40 percent of the population of the Philippines. . When groups such as the Cebuano, Ilonggo, and Waray are excluded and recognized as their own ethnic groups, the number of Visayans shrinks to 15,522,998, as recorded by the 2020 Philippines census. [Source: Wikipedia]

Visayans are seen as passionate, fun-loving, musical and courageous. Like the Luzon lowlanders—such as the Tagalogs and Ilocanos—the Visayans have a strong maritime culture. and are mostly Roman Catholic. They make up a proportionally high number of professional fighters in the Philippines military and have played a major role in fighting the Islamic groups in Mindanao. They have traditionally been farmers who cultivated corn and wet rice. The Visayans include the Samarans, Panyans and Cebuans, who live on Samar, Panay, Cebu, Bohol, Leyte, Masbate, Negros and Siqijor. Many live outside the region, particularly in Manila and on Mindanao.

The Visayan Islands form a large island group in the central Philippines, covering about 62,160 square kilometers (24,000 square miles) around the Visayan Sea. Major islands include Bohol, Cebu, Leyte, Masbate, Negros, Panay, and Samar, along with many smaller islands. Samar and Leyte lie to the east and help shield the region from strong Pacific storms, contributing to a relatively mild climate that supports intensive farming. The coastal plains of Samar and Leyte are heavily populated, while Cebu, Negros, and Panay serve as the region’s economic centers. Cebu City stands out as a major hub for trade, transportation, industry, and culture in the Visayas. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.]

Visayan (Bisayan) Languages and Identity: Visayan (Bisayan)Languages are commonly referred to as Binisaya or Bisaya. The most widely used is Cebuano, followed by Hiligaynon (Ilonggo) and Waray-Waray. While these languages are classified as "Bisayan" by linguistic terminology, not all speakers identify as Visayan ethnically or culturally. The predominantly Muslim Tausug people, for example, prefer to identify as part of the Moro ethnic group. They use the term "Bisaya" to refer to the predominantly Christian lowland natives despite speaking the Bisayan Tausug language and being closely related to the Visayan Surigaonon and Butuanon peoples. Conversely, the natives of Capul in Northern Samar speak Abaknon, a Sama–Bajau language, yet they identify as culturally Visayan. The Ati people also distinguish themselves from other Negritos despite being native to the Visayan islands.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS ON PALAWAN factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS AND MINORITIES IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF LUZON: TAGALOGS, ILOCANO AND BICOL factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

LUMAD (INDIGENOUS ETHNIC GROUPS) OF MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Visayan History

The Visayans were a historical people broadly corresponding to today’s speakers of Visayan languages. They appear in medieval and Renaissance records from Chinese, Bruneian, and early Spanish sources. These accounts describe them as skilled traders and seafarers, a livelihood shaped partly by limited farmland in many of their islands. They were also known for their warrior culture, leading maritime expeditions, conquests, and slave raids across parts of East and Southeast Asia. [Source: Wikipedia]

In Ming-era Chinese records, the Visayans were referred to as Pisheye (or Peshiye). These accounts describe coastal communities with little agriculture, which matches places like Cebu. Observers noted that men and women wore their hair in topknots and tattooed their bodies up to the neck, consistent with descriptions of the Pintados (“the tattooed ones”) later recorded by the Spanish. Chinese sources also stated that Pisheye had “no paramount chief,” suggesting it was not a single unified kingdom but a collection of independent settlements.

Some scholars have offered interpretations of these references. In 2004, Efren Isorena suggested that the “Pisheye” were likely Visayan sea raiders from Ibabao (eastern Samar), whose balangay boats with bamboo outriggers may have been misunderstood by foreign observers as simple rafts. Historian Robert Nicholl proposed possible connections between the Visayans, the Srivijayans of Sumatra, and the Vijayans of Brunei, viewing them as part of a broader regional network. Similarly, Spanish missionary-historian Francisco Colin wrote that the people of Panay may have originally come from northern Sumatra, reflecting longstanding ideas of migration and cultural links across maritime Southeast Asia.

Visayan Religion

Like the Luzon lowlanders—such as the Tagalogs and Ilocanos—the Visayans were originally animist-polytheists. This changed in the 16th century when Spanish rule established Roman Catholicism as the state religion. In more remote inland areas, older beliefs did not completely disappear but were blended with or reinterpreted through Catholic teachings.

According to 2000 survey, 86.5 percent of the population of Western Visayas identified as Roman Catholics, four percent said they were Aglipayan, 1.5 percent were Protestant Evangelicals, while 7.7 percent said they had no religious affiliations. The same survey showed that 92 percent of the population in Central Visayas was Catholic, followed by 2 percent who were Aglipayans and 1 percent who were Evangelical. The remaining five percent belonged to the United Church of Christ in the Philippines, the Iglesia ni Cristo, various Protestant denominations, or other religions. [Source: Wikipedia]

In Eastern Visayas, 93 percent of the total household population was Catholic, while 12 percent identified as Aglipayan and 1 percent as Evangelical. The remaining 5 percent belonged to other Protestant denominations, including the Iglesia ni Cristo, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and various Baptist churches, or identified with Islam and other religions. The Muslim Tausūg people are excluded from these statistics, as they do not identify as Visayans and are classified among the Moro ethnic groups.

Precolonial Visayans practiced a complex animist and Hindu-Buddhist belief system centered on spirits, nature deities, and a pantheon led by supreme gods. Kaptan (god of the sky) and Magwayan (goddess of the sea and death) were central figures, along with their descendants who ruled over the wind, sea, sun, moon, stars, and the world. These deities, collectively called diwata, were believed to inhabit rivers, forests, and mountains, making certain places sacred and even dangerous. Early Spanish colonizers sometimes misinterpreted these beliefs as monotheistic and labeled some diwata as evil. Ancestor spirits, known as umalagad (or anito), were also venerated through offerings and rituals.

The Visayans believed that death involved spiritual transition: the deity Pandaki brought death, while Magwayen ferried souls to Solad, the land of the dead. Good souls eventually reached heaven (Ologan), while bad souls faced punishment, though families could help them through rituals and prayers performed by spiritual leaders.

Religious rituals were led by babaylan, predominantly women or individuals with feminine traits, who served as shamans and intermediaries between humans and spirits. They conducted ceremonies such as the Pag-aanito, which involved animal sacrifices (usually pigs or chickens), offerings of food and wine, and ritual dancing accompanied by drums and gongs. Babaylan were highly respected in society and sometimes played political roles.

Visayan Culture

Visayan Festivals such as Ati-Atihan, Dinagyang, Pintados-Kasadyaan, Sangyaw, and Sinulog are well-known. While these celebrations are strongly rooted in Roman Catholic devotion—especially to the Santo Niño—they also incorporate older Hindu-Buddhist and animist elements seen in traditional dances and imagery. The Santo Niño de Cebú is the oldest surviving Catholic religious image in the Philippines and remains central to many of these festivals. The Sandugo Festival in Bohol reenacts the historic blood compact between Datu Sikatuna and Miguel López de Legazpi, symbolizing early Filipino-Spanish relations. The Binirayan Festival in Antique commemorates the legendary arrival of the ten Bornean datus from the Maragtas tradition. Meanwhile, Bacolod’s MassKara Festival, launched in 1980 after regional hardships, celebrates the city’s resilience and identity as the “City of Smiles.” [Source: Wikipedia]

Visayan Folk Music remains influential in Philippine culture with songs like “Dandansoy,” originally in Hiligaynon but now sung in other Bisayan languages. The song “Waray-Waray,” though written in Tagalog, highlights stereotypes and positive traits of the Waray people and was even performed by jazz singer Eartha Kitt. The popular Filipino Christmas carol “Ang Pasko ay Sumapit” was originally the Cebuano song “Kasadya Ning Taknaa.” Visayan artists have also significantly shaped contemporary Philippine music. Prominent figures from the 1960s to the 1990s include Jose Mari Chan, Pilita Corrales, Dulce, Verni Varga, Susan Fuentes, Jaya, and Kuh Ledesma, while newer generations feature performers such as Jed Madela, Sheryn Regis, and Sitti Navarro.

Dances from the Visayan region are recognized through the Philippines. The most well-known dance is the tinikling, which is said to originate from Samar-Leyte. The curacha, also known as the kuratsa, is a popular Waray dance that should not be confused with the Zamboangueño dish of the same name. Its Cebuano counterparts are the kuradang and la berde. Some Hiligaynon dances include the harito, balitaw, liay, lalong kalong, imbong, inay-inay, and binanog. There is also the liki from Negros Occidental.

Actors with Visayan roots have contributed significantly to the Philippines film and television industry. Established figures include Joel Torre, Jackie Lou Blanco, Edu Manzano, Manilyn Reynes, Vina Morales, Cesar Montano, and others. A younger generation of Visayan-descended performers—such as Kim Chiu, Enrique Gil, Shaina Magdayao, Carla Abellana, Erich Gonzales, and Matteo Guidicelli—continues this influence in contemporary Philippine entertainment.

Visayan Tattooing and Body Adornment

Tattoos were once a big part of Visayan culture. The original Spanish name for the Visayans, Los Pintados ("The Painted Ones") was a reference to the tattoos of the Visayans. Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan expedition (1521) repeatedly describes the Visayans they encountered as "painted all over". In 1604, Pedro Chirino wrote in “Relación de las Islas Filipinas”: The Visayan language itself had various terminologies relating to tattoos like kulmat ("to show off new tattoos) and hundawas ("to bare the chest and show off tattoos for bravado")”. Tattoos were acquired gradually over the years, and it could take months for a pattern to be completed and healed. [Source: Wikipedia]

The first tattoos were acquired during rites of passage into adulthood. Initially, they were made on the ankles and gradually moved up the legs and finally to the waist. Tattoo designs varied by region. Examples include repeating geometric designs, stylized representations of animals (such as snakes and lizards), and floral or sun-like patterns. The most basic design was the labid, an inch-wide, continuous tattoo of straight or zigzagging lines covering the legs to the waist. Shoulder tattoos were known as ablay, chest tattoos up to the throat were known as dubdub, and arm tattoos were known as daya-daya (or tagur in Panay). Visayan tattooing traditions, however, have been lost over the centuries during Christianization in the Spanish colonial period.

Visayans practiced various forms of body modification in addition to tattooing. One major practice was artificial cranial deformation, where infants’ foreheads were shaped using a device called a tangad to create an elongated skull; adults with this ideal shape were called tinangad, while unshaped skulls were known as ondo Men underwent circumcision (more accurately supercision) and sometimes practiced pearling or wore genital piercings called tugbuk, secured with decorative rivets known as sakra. Both men and women pierced their ears—men typically with one or two piercings, women with three or four—and wore large earrings, earplugs, or pendants. Other modifications included gold tooth fillings, especially among renowned warriors, as well as teeth filing and blackening, reflecting cultural standards of beauty and status.

Cebuano

Cebuanos are the largest Visayan subgroup and often ranked as the third largest ethnic group in the Philippines, making up 8 to 13 percent of the Philippines population and numbering around 20 million according to a 2023 estimate.. They originate from the Central Visayas island, which include Cebu, Siquijor, Bohol, Negros Oriental, western and southern Leyte, western Samar, and Masbate. A large number of them, mainly from recent migrations, live in large parts of Mindanao. n general, "Cebuano" refers to the native speakers of the Cebuano language in various regions of the Philippine archipelago. More specifically, "Cebuano" (Cebuano: Sugbuanon) refers to the native inhabitants of Cebu Island. [Source: Wikipedia]

The earliest European account of the Cebuanos comes from Antonio Pigafetta, a member of Magellan’s expedition, who recorded aspects of their customs and documented samples of the Cebuano language. Ferdinand Magellan himself was killed in Cebu during the Battle of Mactan against the forces of Lapulapu. Cebuanos played a significant role in early Spanish colonial campaigns, including the conquest of Luzon and Manila, where around 300 Visayans supported 90 Spaniards. They also served as important intermediaries in trade between China and Spain during the early colonial period.

For centuries, Cebuanos have migrated in large numbers, with major waves occurring in the early to mid-20th century due to economic hardship, displacement, and government-sponsored resettlement programs. Migration to Mindanao intensified in the 1930s and 1950s, leading to Cebuano becoming the dominant language in many areas. Migrants often relocated in groups, preserving their language and culture, and—together with settlers from Bohol and Panay—helped establish Cebuano as the lingua franca of much of Mindanao.

The Cebuano Language is the most widely spoken of the Visayan languages. Most Cebuano speakers are found in Cebu, Bohol, Siquijor, southeastern Masbate, Biliran, western and southern Leyte, and eastern Negros, as well as most of Mindanao, except the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. As with other Filipino ethnic groups, Cebuanos also speak Tagalog (Filipino) and English as second languages. Despite being one of the largest ethnic groups, Cebuanos tend to fluently learn the native languages of the areas where they have settled, along with Cebuano.

Cebuano Festivals, Films and Weddings

The Sinulog Festival, held every third Sunday of January in Cebu City, is one of the island’s most important celebrations. It blends Christian devotion—particularly to the Santo Niño—with indigenous cultural elements. Cebuanos are part of the Philippines’ dominant Lowland Christian culture, and the majority are Roman Catholic. In some rural areas, Catholicism is blended with indigenous Bisayan folk beliefs, while a minority—especially in Mindanao or among Chinese-Cebuano families—combine Catholic practices with elements of Buddhism or Taoism.

Cebuano-language cinema experienced a golden age from the 1940s to the 1970s, producing numerous films. This era was led by Gloria Sevilla, known as the “Queen of Visayan Movies,” along with other prominent actors such as Caridad Sanchez, Lorna Mirasol, Chanda Romero, Pilar Pilapil, and Suzette Ranillo.

Traditional Cebuano weddings are elaborate, often beginning with a large celebration at the bride’s home financed by the groom’s family. Brides typically wear white satin gowns and carry white flowers, while grooms wear a white barong Tagalog. Wealthy weddings may feature choirs, bells, and aisles decorated with candles and flowers. During the ceremony, rings are exchanged, followed by the Spanish-influenced coin ritual in which the groom places gold or silver coins into the bride’s hands, symbolizing prosperity. In the Laso ceremony, a veil and cord are placed over the couple to represent unity. [Source: kasal.com ^]

After the ceremony, the couple is welcomed with festive decorations of coconut palms and banana plants and may be accompanied by music and dancing as the bride is symbolically brought to the groom’s home. Distinctive traditional marriage arrangements include Balusay and Luka-Ay, or “marriage by pair,” involving sibling pairs from two families marrying one another, reinforcing family alliances and kinship ties.

Waray People

The Waray people by some reckonings are the sixth or seventh largest ethnic group in the Philippines, making up 3.8 percent of the Philippine population and numbering 4,106,539 people in the 2020 census. Also known as the Waray-Waray, they are a subgroup of the larger Visayan group and inhabit most of Samar, where they are called Samareños or Samarnons; the northern part of Leyte, where they are called Leyteños; and Biliran Island. On Leyte Island, the Waray-speaking people are separated from the Cebuano-speaking Leyteños by the island's central mountain range. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Waray people have ancient roots in Eastern Visayas with evidence of early human presence in Sohoton Caves, Samar, dating back to around 8,550 B.C., where stone flake tools used by hunter-gatherers were discovered. The Warays later descended from Austronesian-speaking seafarers who settled the region during the Iron Age and developed complex societies that traded with Chinese, Bornean, and Malay groups. In 1521, the Warays of Samar—called Ibabaonon—were among the first inhabitants of the Philippines encountered by Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition.

Most Warays are Catholic. The Waray were also among the earliest indigenous groups to convert to Christianity, yet they remain notable for retaining indigenous traditions alongside Roman Catholic practices. In modern times, the Warays have faced cultural and linguistic marginalization, as their language, Waray-Waray, is often classified nationally as a dialect rather than a distinct language outside Samar and Leyte.

Language: The Waray people speak Waray, a major Visayan language. Many also speak English, Tagalog, Bicolano and/or Cebuano as their second languages. Some people of Waray descent speak Waray as their second or third language, especially among emigrants to Metro Manila, other parts of the Philippines (especially in Mindanao), and elsewhere in the world. The term “Waray” refers to both the people of Samar and Leyte and their language; in Waray, the word means “nothing,” though how it became the language’s name is unclear. Formally, the language was called Lineyte-Samarnon or Binisaya, but “Waray” eventually became the widely accepted official term.

Waray is is an Austronesian language native to Samar, Leyte, and Biliran, which together form the Eastern Visayas region of the Philippines. Waray is mainly spoken on Samar Island, although Cebuano is used in some areas. The language has distinct regional variants: Estehanon (Eastern Samar), Nortehanon (Northern Samar), and Westehanon or Kinalbayog/Calbayognon (Western Samar), each differing in vocabulary, tone, and accent. Warays may also identify themselves according to these regional varieties.

Waray Character and Culture

The Waray are often stereotyped as brave and fearless, reflected in the popular saying, “Basta ang Waray, hindi uurong sa away” (“A Waray never backs down from a fight”). However, the more negative image of Warays as violent or aggressive largely stemmed from the notoriety of certain Waray gangs rather than from the broader population.Northern Samar, a historically resistant region, has been a stronghold of the New People’s Army (NPA), partly due to its legacy of anti-colonial struggle and enduring cultural ties to a precolonial warrior tradition. Many NPA fighters in the area are of Waray and Cebuano descent. [Source:

At the same time, Warays are also associated with a “contentment culture.” During the Spanish period, they were sometimes labeled as lazy because they were satisfied with a simple farming lifestyle and the production of tuba (coconut palm wine). In contrast to warrior stereotypes, Warays are also known for their love of music and dance, particularly the Kuratsa, a traditional courtship dance.

The folk song “Waray-Waray” gained international recognition in the 1960s when American entertainer Eartha Kitt recorded and performed her own version. Sung in a mix of Tagalog, Visayan, and some English, her rendition was notable for its rough delivery, mispronunciations, and invented words—contrasting with her smoother performances in other languages. Originally composed by Juan Silos Jr. with lyrics by Levi Celerio, the song focuses on Waray women and reinforces stereotypes portraying them as brave, combative, and unafraid, contributing to broader discussions of Filipina identity.

Many Waray traditions trace their roots to precolonial times, particularly the Kuratsa, a traditional courtship dance commonly performed at weddings and social gatherings. Although once thought to have Mexican origins, it has been officially recognized as indigenous to the Waray people. The dance imitates the movements of a rooster and hen and is typically accompanied by a rondalla or live string band, with music varying depending on the performers.

The Kuratsa is central to Waray cultural life and features intricate, synchronized steps between partners. Men perform agile, energetic movements symbolizing the rooster’s vigor, while women execute graceful, flowing steps representing the hen. The dance often includes dramatized courtship sequences such as the palanat (chase), dagit (swoop), and wali (lift), as well as the gapus-gapusay, where partners are symbolically tied together while guests shower them with money.

The Kuratsa plays a key role in Waray wedding rituals known as bakayaw, where the bride and groom dance and receive monetary offerings symbolizing blessings and prosperity. In 2011, it was recognized by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts as part of the Philippines’ intangible cultural heritage. In addition to dance traditions, Warays also produce native wines such as tuba (coconut palm wine), manyang (from palm trees), and pangasi (fermented rice wine).

Hiligaynon (Ilongo) People

The Hiligaynon are the fourth or fifth largest ethnic group in the Philippines, making up about 8.5 percent of the Philippines population and numbering 8,608,191 in the 2020 Philippines census. Widely known as Ilonggo and sometimes referred to Panayan people, they are the second largest Visayan subgroup. They originated in Iloilo province on the island of Panay, in the region of Western Visayas. Inter- and intra-island migrations have spread the Hiligaynon people beyond Iloilo, where they originated. Today, they form majorities in Guimaras, Negros Occidental, and Capiz, and have significant populations in parts of Mindanao, including South Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, Cotabato Province, and areas of Sarangani. [Source: Wikipedia]

Most Hiligaynons are Roman Catholics. The term “Hiligaynon” comes from the Spanish Hiligueinos (earlier spelled Yliguenes or similar forms), derived from the older name Iligan or Iliganon, meaning “people of the coast.” It originates from the root word ilig (“to go downstream”), referring to a river in Iloilo. Early Spanish accounts also used similar terms for other coastal Visayan groups. The word “Ilonggo” comes from Ilong-ilong, the former name of Iloilo City. “Ilonggo” generally refers to the people whose ethnic roots trace to Iloilo, Guimaras, and Panay, while “Hiligaynon” refers more specifically to their language and culture. In practice, the two terms are often used interchangeably.

The original inhabitants of Western Visayas were the Negritos, particularly the Ati people in Panay. Malay-speaking peoples settled in the island in the 13th century,[dubious – discuss] but some of the facts of this settlements are clouded by folk mythology among the Hiligaynon. What is known[dubious – discuss] is that in the 13th century, ten datu (chieftains) arrived from Borneo, fleeing the collapse of a central Indonesian empire. The Ati agreed to allow the newcomers to settle, who had purchased the island from them, and the island was named Madya-as. Since then, political organization was introduced to Panay under the Malay newcomers.[6] By the arrival of the Spanish in 1569, the inhabitants of Panay were well-organized, yet became part of Spanish colonial rule.

In the 19th century, large numbers of Hiligaynon migrated from Panay to Negros due to the rapid expansion of the sugarcane industry. The decline of the textile industry in Panay increased the labor supply available for plantation work, while Spanish colonial authorities actively encouraged migration. As a result, Negros’ population grew dramatically—from about 49,000 in 1822 to 756,000 by 1876, matching Panay’s population. During this period, many prominent revolutionaries seeking independence from Spain were Hiligaynon, including reformist leader Graciano López Jaena and military figure Martin Delgado, known as a leading Visayan general of the Philippine Revolution.

In the 20th century, another major wave of Hiligaynon migration occurred, this time to Mindanao during the 1940s and 1950s under President Manuel Roxas, who was himself Hiligaynon. The government-sponsored resettlement program aimed to address land issues but often bypassed meaningful land reform. This migration significantly affected the local Maguindanaon population, who received little government support, contributing to long-term tensions between the predominantly Christian Hiligaynon settlers and the Muslim Maguindanaon communities.

Hiligaynon (Ilongo) Culture

The Hiligaynon celebrate several famous festivals and events, most notably the Dinagyang Festival in Iloilo City, held every fourth Sunday of January. Inspired by the Ati-Atihan of Aklan, Dinagyang honors the Santo Niño and commemorates the legendary purchase of Panay Island from the Ati by ten Bornean datus. Other cultural events, such as the Ilonggo Arts Festival, promote heritage through performances and modern media. The Iloilo Paraw Regatta, held each February, features traditional paraw sailboats and highlights maritime heritage, with local fishermen competing in sea races accompanied by land-based festivities. [Source: Wikipedia]

Hiligaynons are regarded as being good at sports, particularly football (soccer , which is popular in Western Visayas. Iloilo—especially the town of Barotac Nuevo—has produced many national football players, including Phil and James Younghusband, who have Ilonggo heritage. Hiligaynon athletes have also represented the Philippines in track and field.

Weaving has long been part of Hiligaynon culture. Introduced through early trade with the Chinese, the craft flourished by the 1850s when Iloilo became known as the Philippines’ “textile capital,” producing piña, silk, jusi, and sinamay fabrics for export. However, weaving declined later in the century due to the rise of the sugar industry and competition from cheap imported textiles. Today, the industry survives through specialty fabrics like hablon, supported by government initiatives and niche markets.

Hablon weaving is traditionally practiced by women, especially in Miagao, Iloilo, with skills passed from mother to daughter. The fabric is used for barongs, shawls, scarves, and household décor, and is sold locally and abroad. Weaving communities in Iloilo and Kabankalan continue to preserve the craft, and hablon designs have even been featured in tourism campaigns, showcasing the enduring cultural significance of Ilonggo textiles.

Hanunoo

The Hanunoo is a group that lives in southern Mindoro. Also known as the Bulakakao, Hamangan, Hanono-o, Mangyan, they have their own Indic-derived script which they say has traditionally written on bamboo. For a long time they had little contact with outsiders other than to trade forest products for metal and European-made glass beads, which are sometimes exchanged like money and used to settle disputes. Their villages are autonomous and have no chiefs. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

The Hanunoo live in wood, bamboo and thatch houses that are joined end to end and share a veranda. Their granaries look like houses but are smaller and lack a veranda. Their villages tend to be small, with only two to twelve semipermanent houses. They are primarily slash-and burn agriculturalists who plant corn, beans, sugar cane, bananas, papayas and other crops and hunt monkeys, wild pigs, deer and wild water buffalo with poisoned arrows, traps, dogs and fire surrounds. They use scrap metal and bamboo double piston bellows to fashion metal tools. In the 1990s, some Mangyans still wore loincloths. They traded beeswax and honey for goods with the Spaniards after they arrived. Catholic missionaries are working to protect Mangyan land rights and preserve their culture.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Hanunoo population in the early 2020s was 24,000. Most practiced traditional animist religions and 10 to 50 percent were Christian, with 5 to 10 percent of these being Protestant Evangelicals. The Hanunoo have traditionally believed in guardian spirits and ghosts of the dead. The guardian spirits are appeased with periodic offerings of rice, pig blood and betel nut and strings of glass beads. Should these duties be ignored, the Hanunoo believe, the spirits may become angry and allow evil spirits to bring disease and misfortune. Illnesses are treated with herbs, massages and rituals involving mediums (“ balyanan”) who call on spirits that live in stones to cast out the evil spirits.

Young men and women have traditionally courted each other at “ panludan” feasts by exchanging love songs accompanied by guitars, nose flutes and Jew’s harps. Marriage takes places after an agreement has been reached between families. There is no ceremony, bride price or exchange of gifts. Most couples reside with the bride’s family.

The Hanunoo do not practice warfare but family members of murder victims are allowed to take revenge. Sometimes an ordeal with hot water is used to determine the truth at judicial proceedings. The dead are buried for a year and their bones are exhumed and taken to a feast and danced with in an elaborate ceremony and then placed in a niche in a cave. The Hanunoo believe that if this is not done the spirits of the dead may come back to haunt them.

Sulod

The Sulod are a mountain people that live on the banks of the Panay River on central Panay island. Also known as the Suludnon, Buki (now considered derogatory), Bukidnon, Montesses, Mondo, Panay-Bukidnon, Pan-ayanon, Tumandok, Mundo and Putian, they are primarily agriculturist but also do some hunting and fishing. They live in small settlements on raised one-room bamboo and wood houses. They hold 16 annual ceremonies to honor their pantheon of spirits. The oldest man in each settlement is the chief. When girls and boys reach the age of puberty, they are believed to be old enough to chew betel nut and file their teeth. From then on they are considered mature.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993), Teresita R. Infante, kasal.com]

The Sulod are the largest and most diverse ethnic group in Central Panay, with communities in Capiz, Iloilo, and Antique. mundos, they primarily speak the Sulod language, or Ligbok, which is closely related to Hiniraya. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 34,000 Sulod in the early 2020s. Another sources listed their population at 81,189 in 2010.

The Sulod are especially known for their binukot tradition, the binanog dance, and the epic Hinilawod. One of their most distinctive customs is the binukot tradition, in which selected beautiful young women are secluded and trained as cultural record keepers. These women memorize important Visayan epics such as Hinilawod and are treated like princesses. When they reach marriageable age, they are formally offered for marriage. This practice highlights the Sulod’s strong emphasis on oral tradition and cultural preservation. [Source: Ethnic Groups Philippines]

The Sulod practice shifting cultivation, usually staying in one place for no more than two years while growing upland rice and other crops. They live in small settlements called puro, typically composed of five to seven houses built on ridges near rivers. Each puro is led by the eldest man, the parangkuton, who oversees community activities, rituals, and dispute resolution, assisted by a timbang.

According to Joshua Project most Sulod practice traditional animist religions. About 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with many of these being Protestant Evangelicals. In their traditional religion, a spiritual leader called the baylan communicates with spirits and leads major annual ceremonies honoring their principal diwata. Their culture features vibrant artistic traditions, including the eagle-inspired binanog dance, epic chanting, bamboo instruments, and intricate panubok embroidery. Funeral practices vary by status: ordinary members are buried, while important figures undergo special secondary burial rites, reflecting beliefs in predestined death determined by mythological beings.

Ati of the Visayan Islands

The Ati are a Negrito group and the indigenous peoples of the Visayan Islands, Found principally on the islands of Boracay, Panay and Negros, they are genetically related to other Negrito ethnic groups in the Philippines such as the Aeta, Batak, Agta and Mamanwa of Mindanao.According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Ati Negrito population in the late 2020s was 13,000. The Ati speak a distinct language known as Inati, which had about 1,500 speakers according to a 1980 census. Many Ati also speak Hiligaynon and Kinaray-a, reflecting long-standing contact with neighboring populations. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project]

The Philippine legend of the Ten Bornean Datus recounts the arrival of Bisaya ancestors in Panay in the early 12th century after fleeing persecution in Borneo. According to the legend, land was peacefully exchanged with Ati leaders, leaving the uplands to the Ati and the lowlands to the newcomers. This event is commemorated in the Ati-atihan festival, though historians debate the historical accuracy of the account.

Traditionally nomadic, the Ati of Panay were considered the most mobile among Negrito groups. In recent times, most have settled in permanent communities in places such as Barotac Viejo, Guimaras Island, Igkaputol (Dao), Tina (Hamtic), and Badiang (San Jose de Buenavista). Today, only a small number of Ati remain semi-nomadic, mainly women with young children. Ati men often engage in seasonal labor as sacadas during sugarcane harvests in areas such as Negros and Batangas.

See Separate Article: NEGRITOS OF THE PHILIPPINES: HISTORY, GROUPS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Philippines Department of Tourism, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026