TORAJAN PEOPLE

The Torajan people live in highlands and mountainous areas of South Sulawesi and Central Sulawesi. Also known as the Sa’dan Torajans, South Torajans, Tae’ Toraja, Toraa, Toraya, they are well know for their elaborate funeral rituals and cliff side graves and totems. Even though many are Christians they keep alive their old customs. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Discovered” and opened to the world from their long isolation only since the beginning of the 20th century, the Torajan people today still adhere to their age-old beliefs, rituals and traditions, although many have modernized or have embraced Christianity. Torajan nobility are believed to be descendents of heavenly beings who came down by a heavenly stairway to live here on earth in their beautiful homeland.To maintain the energy of the land and their people, the Torajan people believe that these must be sustained through rituals that celebrate both life and death, which are attached to the agricultural seasons but rituals connected with life are strictly separated from death rites.

Residing in an area called Tana Toraja, which is sometimes refereed to as the "Land of Heavenly Kings,” the Torajan people cling to ancient tribal traditions and mix them with Protestant Christianity. According to their traditional animist beliefs they believe their ancestors descended from heaven to a mountain top twenty generations ago. Their grand burial ceremonies involve great week-long feasts with buffalos sacrifices, after which the remains of the deceased are placed into a coffin and carried to a hollowed out cliff side cave by a frenzied procession. The opening of the cave is guarded by life-like statues that stand on a "balcony."

The Torajan people have been successful in gaining national and international attention. This group became prominent in the 1980s, largely because of the tourist industry, which was attracted to the region because of the picturesque villages and the group’s spectacular mortuary rites involving the slaughter of water buffalo. Inhabiting the wet, rugged mountains of the interior of southern Sulawesi, the Torajan people grow rice for subsistence and coffee for cash. Traditionally, they lived in fortified hilltop villages with from two to 40 houses featuring large, dramatically sweeping roofs resembling buffalo horns. Until the late 1960s, many of these villages were politically and economically self-sufficient. This autonomy developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries partly as protection against the depredations of the slave trade and partly as a result of intervillage feuding associated with headhunting. [Source: Library of Congress]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TORAJAN RELIGION: AFTERLIFE, PRACTITIONERS, CHRISTIANITY, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN FUNERALS: RITUALS, BELIEFS, COSTS, EVENTS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN BURIALS: TOMBS, TAU TAUS AND THE WALKING DEAD factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN SOCIETY AND LIFE: FAMILIES, FOOD, HOUSES, WORK factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN CULTURE: ART, TEXTILES, MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA TRAVEL: HOTELS, TRANSPORT, GETTING THERE, RAFTING factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA SIGHTS: TRADITIONAL VILLAGES, HOUSES, CLIFFSIDE GRAVES, FUNERAL SITES factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Tana Toraja, Home of the Torajan People

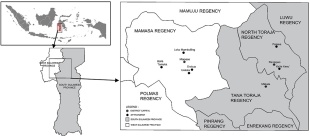

The homeland of the Torajan people is an area called Tana Toraja, Located about 320 kilometers (200 miles) north of Makassar city, it is a rugged and beautiful highland area of lush river valleys, rice terraces, bamboo groves, fir trees, tropical rain forests, coffee plantations, jagged limestone cliffs, and limestone and granite outcrops. There are more than 300 Torajan villages in the area with traditional” tongkonan,” or family dwellings, and rice barns with high upturned roofs." Some of have grave sites. Each site is different and you may be able to see a Torajan funeral, the ultimate expression of Torajan culture.

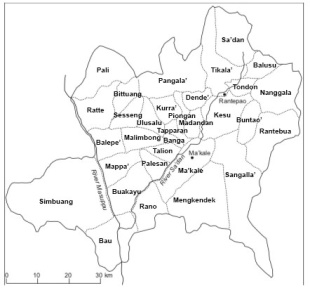

The mountain homeland of the Sa'dan Toraja lies in the northernmost part of the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi. The highlands begin at 1,080 feet (330 meters) above sea level. Paddy fields cover the flat land, which is usually found alongside the many small rivers. The fields rise in terraces up the thickly forested mountainsides. [The major towns of Rantepao and Makale are above 2,300 feet (700 meters), and the highest peak, Mt. Sesean (the abode of Suloara, the legendary first priest of the Torajan people), is 6,560 feet (2,000 meters) high. Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ]

See Separate Article: TANA TORAJA factsanddetails.com

Torajan Groups

The Torajan people are broken down into subgroups. The Torajan group most associated with the group’s unusual custom is the Sa’dan Toraja who are named afer the Sada River, a major river in the area, and live around the towns of Rantepao and Makale. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Toradja is a term used to describe the people who live in the central highlands of Sulawesi. The word “Toradja” means "men of the mountains" and has traditionally been used as a way of differentiated them from lowland people. A number of culturally similar groups fall within this grouping are they are subdivided into Western Toradja, Eastern Toradja and Southern Toradja groups. This classification reflects geographic location as well as varying degrees of historical contact with Hindu-Javanese cultures in southern Sulawesi and the groupings never functioned as distinct political units. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Toradja have been the subject of intense anthropological study because of their head-hunting customs, elaborate funerals, cave burials and carved stone statues. Western Toradja groups include the Mountain Toradja, Pipkoro Toradja, Palu and Parigi. Eastern Toradja groups include the Poso-Toddjo groups, Poso lake groups, Palende, Lampu, Wana and Ampana.. The Southern Toradja groups are generally referred to as Toraja.

Toraja Groups — — Population — Main Religion — Evangelicals — Christians

Toraja-Sa'dan — — 1,018,000 — — Christianity — — 5-10 percent — — 50-100 percent

Pamona — — 186,000 — — Christianity — — 5-10 percent — — 50-100 percent

Banggai — — 182,000 Islam — — 0-0.1 percent — — 10-50 percent

Mamasa Toraja — — 156,000 — — Islam — — 10-50 percent — — 10-50 percent

Mamasa, Pattae' — — 61,000 — — Christianity — — 10-50 percent — — 50-100 percent

Laudje — — 61,000 — — Islam — — 2-5 percent — — 10-50 percent

Bambam — — 37,000 — — Christianity — — 2-5 percent — — 50-100 percent

Kalumpang — — 23,000 — — Christianity — — 5-10 percent — — 50-100 percent

Kulawi — — 9,700 — — Christianity — — 2-5 percent — — 50-100 percent

Napu — — 8,800 — — Ethnic Religions — — 2-5 percent — — 10-50 percent

Seko Padang — — 8,300 — — Christianity — — 2-5 percent — — 50-100 percent

Batui 3,700 — — Islam — — 0-0.1 percent — — 0-0.1 percent

Talondo — — 1,400 — — Christianity — — 2-5 percent — — 50-100 percent

Totals:13 Peoples — — 1,756,000 — — Christianity — — 10.3 percent — — 66.5 percent [Source: Joshua Project]

Toraja Population and Demographics

According to Joshua Project the Torajan population in the early 2020s was 1,756,000 and comprised of 13 groups. The official Tana Toraja website counted 1,100,000 Toraja in 2004. An Indonesian source (Zainuddin Hamka, 2009). listed 600,000 Toraja in South Sulawesi province and 179,846 in West Sulawesi province, where they make up 14 percent of the population and are also known as the Mamasa people. [Source: Joshua Project, Wikipedia]

An estimated 450,000 people live in Tana Toraja— in Sulawesi Selatan, Sulawesi Barat, and Sulawesi Tengah provinces — and 200,000 others have left the region.

Most Sa'dan Toraja still live in their homeland in South Sulawesi's Tana Toraja regency (population in 2005: 437,000). As many as 200,000 Torajans have migrated, primarily settling in the Makassar or Jakarta. These migrants maintain close ties with their ancestral lands. Their money has enabled ordinary families to perform ritual celebrations that were previously reserved for aristocrats. Indeed, this newfound wealth has increased the frequency and elaborateness of ritual activity to unprecedented levels. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Early Toraja History

The Torajan people are ethnically different from the people in Sulawesi. Anthropologists believe Torajans are descended from voyagers who sailed from southern China as early as 3,000 B.C. They had no writing system of their own so most of what is known about them is from Buginese and Makassarese sources. Evidence of relations with the coastal Buginese and Luwunese dates back to the sixteenth century. The Torajan people call their homeland Tana Toradja, Enrekang, Luwu, Poleweli and Mamasa. The Torajans were not united under a single political authority until the arrival of the Dutch colonial forces in 1906. Toraja is a Bugi word that means unsophisticated and roughly means “hillbilly.”

For centuries the Torajan people lived in a state of semi-independent and autonomous mountain villages in southern Sulawesi, occasionally getting into turf battles and headhunting raids with each other or with the Bugis in the south. Slaves and coffee were traded with Muslim lowlanders in return for guns, salt and textiles. Headhunting was never carried out on a large scale. It was primarily a test of manhood and was carried out mostly for the funerals of great chiefs to provide them with slaves for the afterlife. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

While powerful kingdoms emerged in the lowlands of South Sulawesi as early as the fourteenth century, Torajan society lacked political units larger than village confederations (tondok) until the early twentieth century. Collective memory recalls only one brief moment of wider unity: a coordinated resistance against Arung Palakka, the Bugis ally of the Dutch East India Company whose influence extended into the highlands following the fall of Makassar. A tondok could range in scale from a cluster of two or three houses to a far-reaching network of kin spread across the highlands, linking distant settlements through marriage and ritual while excluding nearby communities. In this social order, control of land and the slaves who worked it was the basis of prestige, elevating individuals to the status of to kapua, or “big men.” Animal sacrifice—and the distribution of its meat—served, and continues to serve, as the primary medium through which status and obligations were affirmed. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

By the late nineteenth century, population growth had made land increasingly scarce, rendering the land-poor and landless vulnerable to enslavement for unpaid debts. The slave trade expanded rapidly, fueled by labor demands in the lowlands and by the rise of coffee as a highly profitable export crop in the highlands; some estimates suggest that as many as 12,000 Torajans were sold into captivity. Competition over land rights and trade routes escalated into frequent warfare and slave raiding, prompting villages to relocate to fortified hilltops and to link themselves to neighboring settlements through underground tunnels. ^^

Later Toraja History

Torajan independence ended in 1906, when they fought a war with the Dutch, who wanted to take complete control of Sulawesi. As part of their broader pacification of South Sulawesi, Dutch forces entered the Toraja highlands and by 1908 had subdued resistance led by the to kapua Pong Tiku, who controlled the coffee trade to Bone via Luwu. The Torajans fought the Dutch for two years. The last members of the Toraja resistance were defeated in the mountains around northwest of Ranepao. Defeat by the Dutch also brought a degree of unification among the Toraja which had not existed before. Colonial rule brought an end to slavery and introduced schools, medical clinics, and imported cotton cloth. As elsewhere in the archipelago, local elites adapted to the new order, with to kapua collaborating with the Dutch as officials within the colonial bureaucracy. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Missionaries from the Calvinist reformed Church arrived in 1913 and the region was occupied by the Japanese during World War II. In 1949, the region became part of the newly formed nation of Indonesia. The Torajans hunted heads until the 1920s and they were noted for the ability to raise the dead and make headless corpses walk. The Japanese were supposedly afraid of Torajan magic and afraid to enter their territory. According to one story a group of Japanese soldiers machine gunned down some Torajan resistance fighters who supposedly rose from the dead and their mutilated corpses walked back to their burial grounds. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

The decades following World War II brought profound change to Torajan society. The Kahar Muzakkar rebellion (1950–1965) in the lowlands spilled into the highlands, and fears of forced Islamization led many Torajans to seek protection through conversion to Christianity—a trend reinforced under the New Order regime’s suspicion of non-scriptural religions as potentially communist. In more recent years, voluntary migration, including that of educated professionals, has replaced the earlier outflow of slaves, with returning migrants bringing new wealth back to the Toraja homeland. ^^

With the oil boom in the 1960s and 1970s, there was massive out-migration among young upland Sulawesi men looking for jobs in northeastern Kalimantan. During this period, many of these youths became Christians. Although proselytization began among Torajans in the nineteenth century, mass conversions were provoked after the abortive 1965 coup and mass labor migrations in the 1970s and 1980s, a move that implied a rejection of many Torajan beliefs and practices. But when these migrants returned to their villages as wealthy men, they often wanted to hold large status displays in the form of funerals, causing what anthropologist Toby Alice Volkman has called “ritual inflation” as well as intense debates about the authenticity of their conversion to Christianity. Because of the successful efforts of highly placed Torajan officials in the central government, Torajan feasting practices have been granted official status, loosely described as agama Hindu. [Source: Library of Congress]

Since the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, political instability and widely publicized interethnic and sectarian violence in nearby Central Sulawesi have caused a sharp decline in tourism, deeply affecting a local economy that had grown dependent on it. Torajans have nevertheless worked to prevent such violence from spreading into their region. In September 1997, following anti-Chinese riots that destroyed hundreds of homes and businesses in Ujungpandang (Makassar), Torajans linked arms in the town of Rantepao to block outside Muslim agitators from attacking Chinese-owned shops. At the same time, Muslim transmigrants, as in other parts of Indonesia, began considering a return to their places of origin, fearing retaliation for violence committed elsewhere.

Social Change, Tourism and the Creation of a Torajan Identity

Since their conversion to Islam in the seventeenth century, the lowland peoples of South Sulawesi have used the term “Toraja” to refer broadly to all highland populations who continued to practice ancestral animist beliefs. Dutch colonial anthropologists later identified numerous distinct ethnic groups in the mountainous interior of Sulawesi, loosely categorizing them as Eastern, Western, and Southern Toraja. Of these, only the Southern Toraja—associated with the Saʿdan River valley and best known internationally—eventually adopted the originally pejorative label as a self-designation. In this article, the term Toraja refers specifically to the Saʿdan Toraja. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009^^]

Social change among the Torajans began with the introduction of coffee cultivation and trade in the last quarter of the 19th century. The Dutch subjugation of Toraja country (1906), the Japanese occupation (1942–1945), and Indonesian independence (1945) accelerated this process. By 1913, Calvinist Reformed missionaries had arrived, precipitating dramatic sociocultural changes. Scholars suggest that the activities of these Protestant missionaries stimulated a unifying sense of Torajan identity. Tana Toraja became the missionary field of the Reformed Alliance of the Dutch Reformed Church, and half of the population converted to Christianity. The school system introduced by the Dutch government and missionaries opened a new world for a people who had only known an oral tradition. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Tourism has brought further change. Tana Toraja Regency is a popular tourist destination. Beginning in the 1980s, the Indonesian government actively promoted the region as an international tourist destination, even featuring the traditional noble house (tongkonan) on the 5,000-rupiah banknote. As with Balinese culture, Torajan traditions came to be presented as emblematic of Indonesian national identity. Tourism created new economic opportunities but also introduced significant social and cultural challenges. A total of 179,948 tourists visited the area in 1988. In 2001, Torajan identity received international recognition when Keʾteʾ Kesuʾ, a village renowned for its exemplary tongkonan, was nominated for inclusion on UNESCO’s World Heritage list, alongside Java’s Borobudur and Prambanan.^^

Torajan Languages

The Torajan language is dominant in Tana Toraja, where the principal language is Saʿdan Toraja. Although Bahasa Indonesia is the official national language and widely used in public life, Torajan languages remain central to everyday communication. All elementary schools in Tana Toraja include instruction in the Torajan language. As Indonesian citizens, most Torajans are bilingual, speaking both their local language and Bahasa Indonesia. [Sources: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

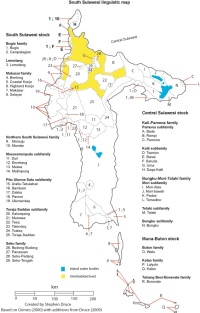

Toraja languages—including Kalumpang, Mamasa, Taeʾ, Talondoʾ, Toalaʾ, and Saʿdan Toraja—belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. The mountainous and historically isolated geography of Tana Toraja fostered the development of numerous local dialects. Following the formal administrative establishment of Tana Toraja, increased mobility and the government-sponsored transmigration program—initiated during the colonial period—introduced new linguistic influences, further diversifying Torajan speech forms.

The Saʿdan Toraja speak Taeʾ, an Austronesian language closely related to the neighboring languages of Duri and Bugis. Taeʾ has two distinct speech levels: a daily, informal register and a higher, ritual language traditionally used by priests. Linguists have reconstructed an ancestral language, Proto–South Sulawesi, from which Saʿdan Toraja, Bugis, Mandar, and Makassar languages are believed to have descended, with particularly close affinities between Saʿdan Toraja and the Duri languages.

A traditional greeting, “Manasumorekka?” (“Have you cooked rice yet?”), is answered with “Manasumo!” (“The rice is already cooked!”), reflecting the centrality of rice in daily life. A distinctive feature of the Torajan language is its rich vocabulary related to grief and mourning. The central role of death rituals in Torajan culture has shaped linguistic expression, producing a nuanced terminology for sadness, longing, depression, and psychological suffering. Articulating the emotional and physical impact of loss is understood as a form of catharsis that can help alleviate grief.

Different Torajan Languages

Major Torajan language varieties include Kalumpang, Mamasa, Taeʾ, Talondoʾ, Toalaʾ, and Torajan–Saʿdan, each with its own dialects and speaker populations ranging from a few hundred to several hundred thousand. Collectively, these languages reflect both the shared cultural heritage and the internal diversity of the Toraja people.

Toraja languages

Kalumpang was spoken by 12,000 people in 1991; Dialects include Karataun, Mablei, Mangki (E'da), Bone Hau (Ta'da).

Mamasa was spoken by 100,000 people in 1991; Dialects include Northern Mamasa, Central Mamasa, Pattae' (Southern Mamasa, Patta' Binuang, Binuang, Tae', Binuang-Paki-Batetanga-Anteapi)

Ta'e was spoken by250,000 people in 1992; Dialects include Rongkong, Northeast Luwu, South Luwu, Bua.

Talondo' was spoken by 500 people in 1986; Dialects include

Toala' was spoken by 30,000 people in 1983; Dialects include Toala', Palili'.

Torajan-Sa'dan was spoken by 500,000 people in 1990; Dialects include Makale (Tallulembangna), Rantepao (Kesu'), Toraja Barat (West Toraja, Mappa-Pana). [Source: Gordon (2005)

Torajan languages are also spoken in neighboring regions such as Luwu and Duri, whose populations are often classified as Bugis due to their Islamic affiliation. The Saʿdan Toraja language is commonly referred to as Bahasa Taeʾ, with taeʾ meaning “no.”

Sa'dan Toraja

When people talk about the Torajan people mostly they are referrin to the Sa'dan Toraja, who live in the highlands of South Sulawesi Province. They speak the Sa'dan Toraja (Tae’ Toraja) dialect and are predominantly Christian. Most reside in Tana Toraja Regency, which covers approximately 3,657 square kilometers (about 1,412 square miles) and is located between 2°40 and 3°25 south latitude and 119°30 and 120°25 east longitude. Elevations range from about 300 to 2,884 meters above sea level (approximately 980 to 9,460 feet).The climate is tropical, with a rainy season from November to April. The Sa'dan River is the major river in the region. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

~

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Toraja-Sa'dan population in the early 2020s was 1,018,000 and 75 percent were Christians, with 5 to 10 percent being Evangelicals In 1987 the population of Tana Toraja Regency was estimated as 346,113. At that time the population density there averaged 84 per square kilometer. Figures are not available for the number of Sa'dan Torajans who have left their homeland to reside in the larger cities of Indonesia (with exception being a 1973 estimate of 30,000 Torajans in Makassar city). In the 2000s an estimated 325,000 Sa'dan Torajans lived in Tana Toraja.

Tana Toraja was originally heavily forested, but most land is under cultivation and the few remaining forests mostly cover slopes unsuitable for cultivation. Agriculture is the main means of subsistence. The staples are rice, cassava, and maize, while the main cash crops are coffee and cloves. Animal husbandry is practiced on a large scale, though only pig breeding is economically important. Buffalo are status symbols and are rarely used for work in the fields. The animal primarily has a ritual function because the most important death feasts require the sacrifice of about a hundred buffalo. ~

Eastern Torajans

The Eastern Torajans live mainly around Lake Poso and in the valleys of the Poso, Laa, and Kalaena rivers in Central Sulawesi. They are also known as the Bare’e, Oost-Toradja, Poso-Todjo, Re’e speakers, To Lage, and Toradja Timur. Their territory is bordered by the Western Torajans to the west, the Mori and Loinang peoples to the east, the Gulf of Tomini to the north, and the former Buginese kingdom of Luwu to the south. North Toraja Regency had an estimated population of about 260,000 in 2023, of which Eastern Torajans made up a large share but exactly how large is not clear. Earlier estimates for the Eastern Torajan population were about 30,000 in 1930, 60,000 in 1935, and 100,000 in 1961, [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

The Bare’e language, spoken by the Eastern Torajans with only dialect differences, belongs to the Toraja language group within the Central and Southern Celebes cluster, mainly a geographical grouping, of Austronesian languages. Torajans populations are commonly divided into Western, Eastern, and Southern branches, each reflecting different levels of influence from Hindu-Javanese states in southwestern Sulawesi and from Borneo.

The Eastern, or Bare’e-speaking, Torajans consist of many local groups with a largely shared language and culture. They form several regional clusters: 1) the Poso-Todjo groups along the Gulf of Tomini and the neck of the eastern peninsula; 2) groups around Lake Poso; 3) groups in the upper Laa Valley east of Lake Poso; and 4) groups in the upper Kalaena region south of Lake Poso. The To Wana and To Ampana peoples east of Lake Poso, although once included among the Eastern Torajans, are better treated as separate groups because of linguistic, physical, and cultural differences; they speak Taa or Tae’ rather than Bare’e.

The Eastern Torajans traditionally practice dry-rice agriculture. Wet-rice cultivation was introduced by the Dutch after 1905 but remained limited. Maize is the second most important crop and is eaten mainly when rice supplies are low. Millet, Coix agrestis, fruits, and vegetables are also grown using swidden farming. Hunting and fishing, especially around Lake Poso, contribute to subsistence.

Weaving is limited, but bark cloth (foeja or fuya) production is well developed. Other crafts include basketry, mat making, pottery, dugout canoe construction, and copper and brass working. Ironworking is especially important; each village traditionally has at least one smith. Iron is believed to possess strong spiritual power, requiring annual rituals to neutralize it and prevent illness attributed to the smithy spirit.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Eastern Toraja: Summary e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu

Mamasa

Mamasa is a highland regency in West Sulawesi, Indonesia, often described as “Toraja’s little sister” because of its close cultural and linguistic ties to Tana Toraja, yet it retains a distinct identity. The people, known as the Mamasa or To Mamasa (often called Toraja Mamasa), are considered a Toraja sub-group who likely migrated from the Toraja Sa’dan area and developed their own community along the Mamasa River. Folklore traces their ancestors to both the sea and the eastern mountains of Sulawesi. The Mamasa language belongs to the Toraja language family and has several dialects, including North, Middle, and South (Pattae’) Mamasa. [Source: Wikipedia, Google AI]

Culturally, Mamasa shares Toraja roots but has evolved unique traditions and expressions. Its traditional houses, called tonan, are wooden, nail-less structures shaped like ships—symbolizing ancestral sea journeys—and are often larger-roofed and more elaborately carved than typical Toraja houses, sometimes featuring horse motifs. Mamasa art includes distinctive dances such as Tondok, Bulu Londong, Malluya, and Burrake, bamboo music played with the pompang flute, and traditional attire marked by woven textiles and bags.

Religion in Mamasa reflects both continuity and change. The ancestral belief system, Ada’ Mappurondo (also known as Aluk Tomatua), remains practiced, especially during post-harvest thanksgiving rituals and traditional funerary customs. Christianity, particularly Protestantism, became dominant in the early 1900s through Dutch missionary influence, leading to the establishment of the Toraja Mamasa Church, while small Muslim and Catholic minorities remain. Funeral ceremonies, including Rambu Solo–style mourning rites and buffalo fights, continue to play an important role in reinforcing kinship ties and social status.

Economically, the Mamasa people are primarily agriculturalists, cultivating rice, corn, cassava, sweet potatoes, legumes, vegetables, fruits, coffee, and cocoa, and raising livestock such as pigs, buffalo, cattle, horses, and poultry. Set amid rugged, scenic highlands, Mamasa is known for its trekking routes between villages and its quieter, less-visited atmosphere compared to Tana Toraja. Altogether, Mamasa offers a culturally rich and secluded glimpse into a Toraja-related world with its own traditions, landscapes, and identity.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026