BUGIS

The Bugis are the predominate ethnic group on the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi. Also known as the Boegineezen, Buginese, To Bugi, To Ugi' and To Wugi' they are one of the most well-known, sea-faring people in Southeast Asia. They have traveled widely and colonized numerous coastal areas and have a long association with piracy. "The Bugis are among the strongest ethnic groups in the archipelago, politically, economically and culturally," Sudirman Nasir, a Bugis who works in public health in South Sulawesi, told the BBC. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Bugis are famous for their Pinisi-rigged schooners which they have used for centuries to travel as far south as the Australian coast where local people made drawing drawings of their ships and they left behind words that have been integrated in the Aboriginal language of North Australia. Bugis have traditionally lived on the coast and the plains are culturally similar to the Makassarese, who dominate the southern tip of Sulawesi peninsula where the Bugis live.

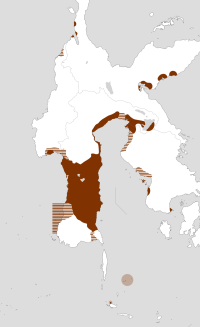

Bugis are the 8th largest ethnic group un Indonesia, making up 2.7 percent of Indonesia’s population, with maybe three fourths of them living in Sulawesi, particularly South Sulawesi. There are around 7 million Bugis (2010 census), with 6,360,000 in Indonesia, 730,000 in Malaysia and 15,000 in Singapore. The estimated number of Bugis speakers in South Sulawesi in the 1970s was around 3.2 million. In the 1990s, it was estimated that around 4 million Bugis lived in South Sulawesi, which had a population at that time of around 7 million. Large numbers of Bugis also lived outside of South Sulawesi.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BUGIS LIFE AND CULTURE: SOCIETY, FAMILY, FIVE-GENDERS factsanddetails.com

BUGIS SAILING TRADITIONS: SHIPS, PIRACY, WHALE SHARKS factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR HISTORY, GOWA, TRADE, RELIGION AND SIRI (HONOR) factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR CITY AND REGION factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON SOUTHERN SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF SOUTHERN SULAWESI: LIFE, SOCIETY, BOATS factsanddetails.com

SOUTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTH EAST SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

TORAJA: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

Where the Bugis Live

Within South Sulawesi Province, the Bugis are concentrated along the coasts of the southwestern peninsula and across the interior rice plains north of Makassar and south of the Tana Toraja highlands. This region, lying roughly between 5° and 4° south latitude along the peninsula’s central axis, contains several agroclimatic zones.

Rainfall patterns vary: the west coast experiences its heaviest rains in December, the east coast is wettest around May, and the interior plains show a bimodal pattern with two distinct dry seasons. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

As traders, fishermen, and farmers, Bugis have settled on their own or through transmigration programs all across Indonesia. They are especially well represented in eastern Sumatra, the Riau Archipelago, along the entire shore line of Sulawesi as well as coastal areas in Kalimantan, the Moluccas, Flores, Buru, and most the islands in eastern Indonesia. ~

Bira, located about 150 kilometers southeast of Makassar, is the main city of the Bugis and one of the best places to observe Bugis maritime culture and wooden shipbuilding.

Further south is the Bulukumba District, which holds an important place in Bugis history. Its name is believed to derive from the phrase bulu’ku mupa, meaning “still my mountain,” which dates back to a 17th-century conflict between the kingdoms of Gowa and Bone over control of the Mount Lompobattang area. Over time, this expression evolved into the name Bulukumba.

Bugis Language

The Bugis have their own language and shared an ancient written language with the Makassarese that is based on the Indic model and has 27 symbols and looks like a "cross section of different but closely related spiral shells.” The Bugis name is derived from a village—“To Ugi” formally on the Cenrana River. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

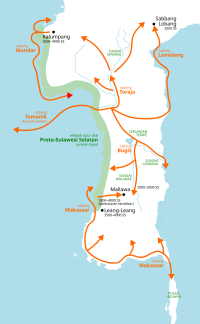

Bugis, Makassar people, Mandar, Sa'dan Toraja, Pitu Ulunna Salo, Seko, and Massenrempulu (Duri) form a distinct South Sulawesi Subbranch within the Western Indonesian Branch of Austronesian languages. Sa'dan Toraja speakers are the closest linguistic relatives of the Bugis, while the speakers of Central Sulawesi languages to the north represent an indigenous population whose occupation preceded that of the South Sulawesi peoples. Bugis and Makassar people share a common script based on an Indic model. In this syllabic script, each of twenty-two symbols stands for a consonant, sometimes prenasalized, plus the inherent vowel a. The five other vowels are indicated by adding diacritics. One further symbol stands for a vowel without a preceding consonant. Writing was developed around 1400, but probably does not derive directly from Javanese kawi.

Traditionally, husbands and wives address each other respectively as "Father of [child's name]" or "Mother of [child's name]," such as in Bugis, "Ambonna/Ambenna Beddu" or "Indonna/Emmakna Beddu" (Beddu being the child). Parents call sons "Baco" and call girls "Becce." Children address fathers with a variety of titles (Ambo, Abba, Puang, Petta, and others) and mothers with Indo, Emmak, Ummi/Mi or a shortened form of the mother's name (e.g., "Lima" for "Halimah"). Older siblings call younger ones by their name or with Anri; younger siblings address older ones with Kaka, Daeng, or sometimes with their name. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Bugis History

The homeland of the Buginese is the area around Lake Tempe and Lake Sidenreng in the Walannae Depression in the southwest peninsula of Sulawesi. It was here that the ancestors of the present-day Bugis settled, probably in the mid- to late second millennium B.C. The area is rich in fish and wildlife and the annual fluctuation of Lake Tempe allows planting of wet rice, while the hills can be farmed by swidden or shifting cultivation. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Bugis are believed to have originated from the Sa’dan River and migrated inland up the Sa’dan valley and across to the Gulf of Boni, where they established their first kingdom, Luwu, which grew rich by dominating the trade of iron and nickel. As time went on a more powerful Bugis kingdom based on a complex network of chiefs and wet-rice agriculture grew up in the south and eclipsed Luwu by the 14th century. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

By the 16th century the Makassar challenged the Bugis for dominance of the region and prevailed by the 17th century. In 1667, the Bugis allied with the Dutch to overthrow the Makassar and established a powerful kingdom that endured through the Dutch period. During this time there was a great diaspora of Bugis, especially those who had been allies of the Makassar. ~

The weakness of the small coastal Malay states led to the immigration of the Bugis, escaping from Dutch colonisation of Sulawesi, who established numerous settlements on the peninsula which they used to interfere with Dutch trade. They seized control of Johor following the assassination of the last Sultan of the old Malacca royal line in 1699. Bugis expanded their power in the present-day Malaysia states of Johor, Kedah, Perak, and Selangor. In the Malay peninsula’s western areas, the Buginese and the Minangkabau, often fought each other. By 1740 the victorious Buginese ruled many peninsular states and continued to do so until they were defeated by an alliance of Johor and the Dutch in 1784.

Bugis mercenaries attained high positions in Aceh, Malaysia , the Riau Archipelago and Thailand and established large settlements in eastern Sumatra. Bugis merchants established strategic trading ports on Kuta in Kalimantan, Johor, north of Singapore, and Selangor, near Kuala Lumpur. ~

The Bugis were notorious mercenaries for the Dutch in the colonial period and their presence often turned the tide in the favor of the Dutch in places like the Riau Archipelago and East Kalimantan. Bugis were also involved in the Indonesia independence movement and thus still remain influential today. The Indonesia government has traditionally kept up a strong military presence in Bugis areas to keep them from rebelling and fighting one another. After Indonesia became independent in 1949, the Kahar Muzakkar's Darul Islam rebellion movement wanted to establish an Islamic state and was brutally put down by the Indonesian government. Bissu priests were arrested, tortured and forced to repent.

Bugis and the Boogey Man

The Bugis also have a reputation for being pirates. The expression "the boogey man is going to get you", some say, can be traced back to the first Europeans that came to the East Indies who, like every one else in the region, feared the Bugis. Bugis pirates often plagued early English and Dutch trading ships of the British East India Company and Dutch East India Company. It is popularly believed that this resulted in the European sailors' bringing their fear of the "Bugis men" back to their home countries.

European mariners greatly feared Bugis pirates. Both Conrad and Melville mentioned the Bugis. Today, Bugis are associated with the rise of piracy in the waters around Indonesia and Southeast Asia. They are thought to be behind some of the pirate attacks in the region. Newspapers have reported Bugis who invaded atolls, burned the villages and made off with an entire year's worth of their cash crop, copra (oil-bearing coconut husks).

Etymologists disagree with assertion that the Bugis were the source of the word boogeyman because words relating to boogeyman were in common use centuries before European colonization of Southeast Asia and it is therefore unlikely that the Bugis would have been commonly known to westerners during that time. The word boogey is thought to be derived from the Middle English bogge/bugge (also the origin of the word bug), and so is generally thought to be a cognate of the German bögge, böggel-mann (English "Boogeyman"). The word could also be linked to many similar words in other European languages: bogle (Scots), boeman (Dutch), Butzemann (German), busemann (Norwegian), bøhmand (Danish), or bòcan, púca, pooka or pookha (Irish). [Source: Wikipedia +]

Bugis Religion

Almost all Bugis are Muslims but they practice a large variety of kinds of Islam, a reflection of their adventures around the world. Most identify themselves as Sunnis. There is a strong Sufi influence. Traditional religion endures in the form of offerings to ancestor spirits and heros. In recent decades, reformist Islamic movements—particularly Muhammadiyah—have gained followers in some areas and have established their own schools and educational networks. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The traditional Bugis universe, as described in ancient Bugis manuscripts (lontara’) and the I La Galigo corpus, contains an upperworld and an underworld, each with seven layers and a host of deities, some of whom nobles trace their ancestry to. Detailed knowledge of this literature, however, is largely confined to specialists and elites. A notable exception to Islamic adherence is the To Lotang community of Sidrap Regency, a non-Muslim Bugis group that maintains an indigenous belief system grounded in lontara’ traditions and closely related to Toraja cosmology. For official recognition, this belief system has been administratively affiliated with Hinduism. The degree to which earlier Hindu-Buddhist ideas shaped Bugis religious and political thought remains a subject of scholarly debate.

The Bugis epic I La Galigo presents a pantheon of deities (dewata), yet contemporary Bugis interpretations often emphasize the existence of a single supreme God, Dewata Seuwa é, aligning the epic with Islamic monotheism. Despite this theological framing, offerings are still made to certain deities—such as the rice goddess—even by practicing Muslims. In village life, Bugis also acknowledge numerous local spirits associated with houses, newborn children, and sacred places. These beings are known by various terms, including to alusu’ (“the ethereal ones”), to tenrita (“those not meant to be seen”), and sétang (“malevolent spirits”). More broadly, every object is believed to possess an animating spirit (sumange’), whose well-being must be maintained to ensure prosperity and to prevent misfortune.

Bugis Religious Practitioners and Celebrations

Most religious duties are led by kali (judges) and taken care of by local iman, who oversee Friday prayers, deliver sermons, and officiate at marriages, funerals, and other Islamic rites. Alongside them are a small number of bissu, ritual specialists traditionally regarded as androgynous priests and former guardians of royal regalia. Though now rare, bissu continue to perform ceremonial chants in a special ritual register of Bugis directed toward deities recognized in the lontara’. Healing and consecration rites are conducted by sanro, ritual practitioners with specialized knowledge of offerings, prayers, and communication with local spirits. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

In addition to the usual Islamic holidays, such as Lebaran and Maulid, there are annual local events, many of them rooted in traditional agricultural festivals and the honoring of guardian spirits with domestic consecration rites (assalamakeng). These ceremonies involve offerings to household spirits, protective beings, and the supernatural siblings of newborn children. Some districts also hold festivals connected with planting and harvest cycles, though many have become largely civic or cultural events. Among the nobility in particular, weddings are elaborate occasions that publicly display status and often include ritual processions and performances. By contrast, bissu rituals have become increasingly restricted and are often carried out without large public audiences.

Funerals follow Islamic rites and are generally not big productions like they are with Toraja. Contemporary Bugis ideas about death are primarily shaped by Islamic concepts of heaven and hell. Nevertheless, among more syncretic communities, spirits of the dead—especially those of former rulers or influential individuals—are still thought to linger and exert influence. Memorial gatherings involving communal prayer and shared meals may be held at set intervals, such as forty days after a death.

Bugis Economics and Trade

South Sulawesi is regarded as the rice bowl of eastern Indonesia and the heartland of the Bugis. The coastal plains are intensively cultivated with wet-rice using miracle rice varieties, fertilizer and pesticides to raise several high yield crops a year. Some farmers use mini-tractors, others still rely on water buffalo and oxen for plowing and plant and harvest by hand. They also raise some chickens and ducks. Where rice is raised as a commercial crop much of the farm work is done by migrant workers, many of them Makassarese, Javanese and Madurese. Many Bugis are sharecroppers who work land owned by landowners, who are descendant of nobles from the Bugis royal era. [Source: Greg Acciaioli, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Bugis are notoriously poor fisherman. When fishing catches are small they often resort to scraping barnacles off the side of their ship and make a soup that tastes like sea water. Even so many Bugis work as fisherman or raise fish in fish ponds. Outside their homeland Bugis are involved in raising pepper, coconuts and cloves as cash crops.

Bugis are famed traders, prahus have traditionally carries cargo up and down the coasts of Sulawesi and between Sulawesi and Borneo and between islands throughout Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The mariners are usually paid half when they pick up the cargo and half when they deliver it. The crew often subsists on corn meal mixed with salt. The cargos include household goods, bicycles, motorbikes, wood and food stuffs.

Bugis also run small shops and kiosks and are the primary vendors of fish, rice, cloth and small goods in urban and rural markets. Chinese have traditionally been the primary merchants and middlemen in Bugis areas. Bugis also produce intricate filagree work for which South Sulawesi is known. Bugis women are regarded as skilled weavers of silk sarongs.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026