TRADITIONAL TORAJAN HOUSE ARCHITECTURE

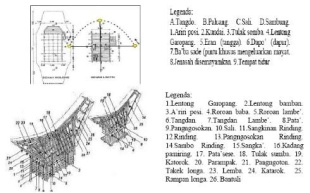

The tongkonan —literally “sitting place”—are among the most striking examples of vernacular architecture in Indonesia. These noble houses function as “origin houses,” where kin gather to resolve disputes, arrange marriages, and discuss inheritance. The most dramatic feature of the tongkonan is its soaring, upturned roof, an impressive structural achievement that appears to defy gravity. Over time, Torajans intensified the height and slope of the front eaves, which often require an additional freestanding post for support. While visually striking, these massive roof structures reduce usable interior space. Tongkonan exteriors, especially the northern front walls, are richly carved and painted with symbolic designs that communicate wealth, rank, and prestige. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Comprised of wood fastened together without nails, tongkonan are constructed upon square wood piles and have a rectangular floor plan. The roof is turned upwards at both ends. It was traditionally made of sago-palms but today are increasingly made with corrugated metal. The bamboo floor can support 30 people or more, sleeping together without mattresses. Suspended cotton sarongs are the only things that divide up the families. Many of the houses are outfit with small holes for spitting betelnut juice and blowing out strings of snot. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Traditional houses are oriented east–west and consist of distinct sections: a raised northern floor used for guest sleeping; a low eastern floor for cooking; a low western floor for dining; and a raised southern floor, higher than the northern section, used as the owner’s sleeping area. Livestock are kept beneath the house. Entry ladders, formerly placed on the long side of the house, are now typically located on the short side. A rice barn stands in front of the house facing south, elevated on round posts to prevent rodent access. Rice barns are decorated with carved scenes depicting death rituals and daily activities such as rice pounding, market trips, and hunting. The platform beneath the barn is used for resting. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The tongkonan is an ancestral house distinct from the banua, or ordinary dwelling, and represents both living and deceased members of a lineage. It functions as a meeting place for family decision-making and ritual activities. The roof projects far beyond the house at both the front and rear, symbolizing water buffalo horns, and often requires additional support poles. The front façade is elaborately carved. The central post (tulak somba) is decorated with water buffalo horns. High-status tongkonan display a kabongo (a carved buffalo head with real horns) and a katik bird figure symbolizing death and fertility.

Exterior carvings are painted in black, white, yellow, and red and include geometric patterns, basket motifs, buffalo horns, animals, and rooster-and-sun designs associated with prosperity. Plant motifs symbolize numerous descendants. Construction and renovation of a tongkonan, especially the raising of the tulak somba, involve sacrificial rituals and require contributions from all descendants linked to the house.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TORAJANS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN SOCIETY AND LIFE: FAMILIES, FOOD, HOUSES, WORK factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN RELIGION: AFTERLIFE, PRACTITIONERS, CHRISTIANITY, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN FUNERALS: RITUALS, BELIEFS, COSTS, EVENTS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN BURIALS: TOMBS, TAU TAUS AND THE WALKING DEAD factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Torajan Literature and Folklore

Poetry was an important form of recreation, and people were attentive to rhythm, rhyme, and metaphor. Different metrical forms were used for different subjects. Prose traditions included animal tales, stories of spirits, and accounts of journeys to the land of souls, as well as proverbs, riddles, and short anecdotes. Many themes paralleled wider Indonesian folklore, such as stories of a spectral tarsier resembling the Kancil or Pelandok of Javanese and Malay traditions.

According to one of several origin myths, the Torajan ancestors arrived in eight canoes (lembang) from an island in the southwest. According to Bugis tradition, the Torajan people descend from a lesser cousin of the supreme god, Batara Guru, whose descendants are Bugis royalty. The Torajans claim that Laki Padada, their ancestor, founded 100 noble lines, including the lowland kingdoms of Luwu, Bone, and Gowa. Despite their adherence to Islam, surviving Luwu royalty sent pigs for the renovation of Laki Padada's house in 1983. ^

One tale explains the origin of a difference between the Torajans and their Muslim neighbors. The Torajan hero Karaeng Dua was born to a pig mother. He traveled to Luwu, where he married a female chief (datu). A mischievous highlander informed the chief that her mother-in-law was a pig. Enraged, the chief collected all the sunlight in her house, leaving Luwu in darkness for three days. During this time, the people feasted on pig to their hearts' content. After three days, the chief released the light, and all the remaining pigs were set free in the forest. The forest became taboo for the Luwu people to enter. ^

Torajan Art and Crafts

Traditional arts include elaborately carved tongkonan houses and rice barns tau tau wooden effigies (see Torajan Tombs), textiles, bamboo containers and flutes adorned with the same geometric motifs found on kindred houses. Taus taus are life-sized effigies of the dead are carved for certain wealthy aristocrats. In the past these effigies (tautau) were very stylized, but recently they have become very realistic. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings; [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Bamboo carving is a major craft, producing the most common souvenirs, such as flutes, tube containers, belts, necklaces, hats, and baskets. Other crafts include ikat weaving and blacksmithing. Local smiths make machetes from scrap metal, such as automobile springs. Textiles, bamboo containers, and flutes are often adorned with geometric motifs similar to those found on the tongkonan houses. Torajan textiles often incorporate a pattern of interconnected figures that suggest abstract human forms. Such patterns appear to suggest genealogical descent and ancestry, depending on whether they read “up” or “down.”

Torajan wood carving, known as pa’ssura (“writing”), is used to express social rank, religious ideas, and ancestral values. Carvings consist of geometric patterns and symbolic motifs such as buffalo (wealth), water plants and animals (fertility), knots and boxes (family unity), and aquatic animals (diligence). The carvings are typically painted in black, white, red, and yellow. Bamboo sticks are used as guides in producing geometric designs. [Source: Wikipedia]

In recent years, carved wooden panels integrating Christian iconography into traditional Torajan scenes and adapting traditional Torajan design motifs, such as pa' barre (sunburst) motifs, to Christian uses have become popular. This is in response to challenges to Indonesia's secular identity from assertions of Islamic identity. Ten percent of the Torajans are Muslim, and these artists have responded by integrating Islamic symbols, such as the crescent and star, into their carvings. In 2022, approximately 125 Torajan carving patterns were granted communal intellectual property protection.

Torajan Music and Dance

Traditional instruments include bamboo flutes, gongs water-buffalo horn horns, geso-geso (a two-stringed vertical fiddle), karombi (Jew's harp), nose flutes, single- and double-headed drums, rice-stalk flutes, coconut-shell viols with rattan strings and bows, bamboo harps, and bamboo buzzers. Jew’s harps were valued for their soft sound.

For such occasions as funeral vigils, singing is mournful and monotonous, the chorus forming a circle linked by their little fingers or by arms around shoulders. One singer leads, and the chorus repeats the verses verbatim. By contrast, church singing in Western harmonies is spontaneous and lively. At funeral and other ritual feasts, boys and girls socialize by taking turns singing to each other (kalinda'da', sengo, londe), including riddles in the verses. Contemporary Torajan songs derive from storytellers' refrains and are accompanied by guitar or the Mandar/Bugis zither (katapi). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Dances are generally found in ceremonial contexts, although tourism has also prompted traditional dance performances. Dances about fishing and fighting, have traditionally had a ritual context but are now often performed for tourists. Noteworthy among traditional dances is the Magellu, a ceremonial dance in which several young girls in beaded costumes sway and flutter their fingers; and the Maganda, in which men attempt to dance wearing a black velvet headdress heavy with silver coins and buffalo horns, usually giving up after a few minutes. ^^

The Raego dance was especially popular. It was performed by a double circle of dancers, with women forming the inner ring and men the outer, moving slowly while songs alternated between solo and chorus sections. War dances involved mock combat and were often punctuated by clowning and obscene gestures. [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

Funeral ceremonies involve a sequence of dances and rituals. Ma’badong consists of all-night chanting by a circle of men and is considered central to the funeral. Ma’randing is a warrior dance honoring the courage of the deceased, while Ma’katia is performed by women and emphasizes generosity and loyalty. Ma’dondan is a celebratory dance performed by youths following the sacrifices of buffalo and pigs. [Source: Wikipedia]

Agricultural rituals also include music and dance. Ma’bugi is a thanksgiving dance, and Ma’gandangi accompanies rice pounding. Ma’bua is a major ceremonial dance governed by Aluk belief and may be performed only once every twelve years. Musical instruments include the pa’suling bamboo flute, the pa’pelle made from palm leaves, and the pa’karombi jaw harp.

Torajan Sports

Although they were officially banned in 1981 for their association with gambling, cockfighting and kickboxing are still enthusiastically pursued for major ceremonies and the harvest festival, respectively, with betting included. Among games, top-spinning contests were especially popular, though they were restricted by taboos at certain times of the year.

“Sisemba” is a form of kick boxing practiced by the Torajans in which contestants are not allowed to use their hands and a winner is crowned after his opponent gives up. It has traditionally been used to train young men to be strong. Sometime mass sisembas with 200 boxers are organized during festivals. “Sibamba” is a combatant sport in which participants go after each other with truncheons and water-buffalo-hide shields.

Torajan fighting cocks have a single sharp five-inch-long spur, dictating a different style than that used in regular cockfights. Losers have their spur leg chopped off with a machete and any bird that runs away is a loser. Winners are pampered and shown off in the community. Bullfights are between male water buffalo who are agitated by chilies stuck up their butts. The animals lock horns with the loser giving up and backing off.

Torajan Ceremonial Textiles

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Among the Toraja people of Sulawesi Island in Indonesia, each family owns a variety of sacred textiles. One of the most versatile types is the sarita, a long, narrow cloth used in diverse ways, depending on ritual context and local tradition. During some rites, the Sa'dan Toraja, in the northern highlands, hang sarita from the gables of the ancestral clan house (tongkonan) as ceremonial banners. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The Sa'dan and the Mamasa Toraja, in the eastern part of the district, use sarita in rituals connected both with the east (associated with life, vitality, and fertility) and the west (associated with death and funerary rites). In one fertility rite, a circle of eight women are united physically and supernaturally by a sarita draped around their shoulders. At funerals, sarita can be worn as headcloths by prominent people, placed on the dead, or used to dress the tau-tau, a wooden effigy representing the deceased. In the Kulawi area, sarita serve as festive garments, worn as waistcloths by men or stitched together to form voluminous women's skirts. The geometric motifs on sarita resemble the design carved on the wood facades of tongkonan and rice barns. The stylized water buffalo on this example, the most prestigious animal for ritual sacrifices, symbolizes the owners' high social status.

A sarita in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made of cotton in the 19th–early 20th century and measures (26 centimeters × 4.9 meters (10.25 inches wide and 16 feet long). Another is (20.3 centimeters × 4.9 meters (eight inches wide and 16 feet long).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection also contains a ceremonial Textile called a porisitutu that is made from Cotton and is 162.5 × 251. 5 centimeters (64 inches high and 99 inches wide. The museum also houses another kind of ceremonial textile called a sekomandi.It was made in the Late 19th–early 20th century from cotton and measures 152.4×190.5 centimeters (60 inches high and 75 inches wide. A porisitutu or sekomandi at the museum is believed to have been made 19th century in Galumpang, Sulawesi. It is made from cotton and is (135.89 x 191.77 centimeters (53.5 inches wide and 75.5 inches long).

Torajan Mawa' Ceremonial Textiles

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Torajan ceremonial textile called Mawa ' or maa'. Made of cotton and paint in Seka Lema, Kampung Mareda in the 19th century, it measures 288.3 x 73 centimeters (113.5 inches wide and 28.75 inches high).Eric Kjellgren wrote: The most sacred ceremonial textiles of the Toraja people of central Sulawesi are the ritual cloths known collectively as mawa' or maa'. According to Torajan belief, some mawa' are of divine origin, first brought to earth by deities or ancestors who descended from heaven. Others are said to have been woven from the body of Luangku, a divine ancestress who married the earth and sprung forth as cotton. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to Torajan oral tradition:

And Luangku said: "I am going to enter into a marriage in the edge of the field, I shall unite myself with the richness of the earth.

When I have reached maturity, when my form has developed fully, then I shall rise on high and bear fruit, like the clouds...

Then shall I be spun, like the threads of a cobweb, then shall I be drawn out, like hairs.

I shall be made into a sarita to lamban with a design of men fording a river, I shall become a maa' with a pattern of swimming men.

I shall become a doti langi' with a cross motif on it, I shall become a maa' to whose folding up there is no end.

Then shall I lie in a basket adorned with a design, cherishing all the precious things put therein with me."

Mawa' made by Torajan artists, such as the work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art are rare. These indigenous mawa' depict imagery and themes that are central to cultural and religious life. Foremost among these are water buffalo, which are the most important form of material wealth among the Toraja and the preeminent sacrificial animals on all significant ceremonial occasions. The at the Met shows a quiet scene of domestic prosperity, which is painted freehand onto the cloth. It depicts a group of herders leading a procession of water buffalo into a central corral in which several birds and a calf also reside. The heads of the water buffalo are tilted ninety degrees in order to emphasize the wide expanse of their horns.

Among the Toraja, those water buffalo with the widest horn spans were the most coveted and valuable. The corral is surrounded, and partially filled by, cross-shaped motifs. The Toraja converted to Christianity beginning in the early twentieth century, but the crosses on this nineteenth-century textile reflect the region 's ancient indigenous imagery. Similar crosses, known as do ti langi' (spots of heaven), were believed to adorn the cloth that veiled Puang Matua, the supreme deity in Toraja religion. Although the central composition on this textile is entirely Toraja in conception and iconography, the rows of thin triangular motifs that appear at either end were inspired by the border designs of the prized Indian trade textiles that comprise the majority of mawa' cloths.

Mawa' Ceremonial and Spiritual Context and Meaning

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Imbued with divine power, which protects and ensures the prosperity and fertility of the community, mawa' are, today as in the past, an indispensable accoutrement of ritual life, appearing in myriad contexts at virtually all major ceremonies. Each mawa' is believed to have specific powers, and many bear individual names. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

During the bua', a feast of purification, mawa' serve as ritual garments for the young virginal women who are the central figures in the ceremony. Swathed from head to toe in layers of mawa' so that their bodies are nearly immobile, the young women sit, shaded by and cushioned with other mawa ', in a sedan chair, which is carried aloft during the rites, which ceremonially wed the human world to the heavens. In other ceremonies mawa' are hung on fences to demarcate sacred spaces and used to wrap drums, whose rhythms drive off malevolent inftuences.

The cloths also play a prominent role in elaborate funeral rites, which are one of the central events of Toraja religious life. Toraja funerals are festive rather than somber occasions, involving lavish displays of heirloom textiles and the sacrifice of large numbers of water buffalo. umerous mawa ' enshroud the deceased and adorn the funeral bier, and a mawa' serves as the symbolic "saddle" for the most prominent sacrificial water buffalo, which will convey the individual to the afterlife. Although all mawa' are employed in similar sacred contexts, their earthly origins are diverse. Most examples consist of imported Indian trade cloths or, less frequently, batik textiles from the island of Java, which came to the region through trade, often many generations ago.

Porilonjong Ceremonial Hangings

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a ceremonial hanging called a porilonjong. Made from cotton in Rongkong probably in 19th century, it measures 4.9 x 1.5 meters (16 x 4.9 feet). Eric Kjellgren wrote: The monumental ceremonial hangings, or porilonjong, of the Torajan people , are among the largest textiles produced in Southeast Asia. The name porilonjong means, literally, "long cloth" or "long ikat," a reference to the vast scale of these ritual textiles. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The artistic vision and technical precision required to conceive and execute these enormous ritual cloths on an elementary backstrap loom are truly astonishing. Toraja looms are relatively narrow, and the completed porilonjong is composed of two separate panels, whose designs are mirror images of each other, sewn together with a seam that runs down the center. The designs are executed in ikat, a complex tying and dyeing technique in which the designs are dyed into the threads before the textile is woven. In order to successfully execute the designs, ikat weavers must keep the overall pattern in their mind and precisely align the bundles of thread throughout the exacting sequence of tying and dye baths required to produce each color that appears in the finished pattern. Most Southeast Asian textiles are produced by a single weaver, but porilonjong are so large and complex that several women often collaborate in the task of tying the i kat designs.

The Rongkong Toraja people used porilonjong to demarcate sacred spaces. Hung horizontally on wood fences, the cloths formed both physical and spiritual walls which separated the supernaturally powerful people, objects, and activities within from the mundane world. 5 These massive textiles were also purchased by neighboring groups, who employed them in different ways. The Sa 'dan Toraja used porilonjong primarily as festive tapestries to adorn the walls of houses and other structures during important ceremonies such as marriages and funerals. 7 The vast majority of porilonjong are adorned with geometric motifs. Examples that include figurative imagery, such as the work at The Met, are rare.

The bold red crocodiles and subtler white deer that adorn this porilonjong may represent totemic species, possibly the mythical founders of the village clans. Crocodiles play an ambiguous role in Toraja cosmology. They can kill, but they are also believed to have the power to bring individuals back from the underworld and to rescue them from death. In Palu Toraja oral tradition, the primordial ancestors of some families are said to have been deer. Although deer were an integral part of Toraja art and re ligious belief, the deer images on this work were likely inftuenced by the imagery of ancient trade textiles.

Both the distinctive leaping, or "dancing," posture of the deer and the curvilinear geometric forms that surround them are strikingly similar to the minute deer images on a group of fifteenth-century textiles collected in the Komering River region of Sumatra. Woven half a millennium and hundreds of miles apart, the deer motifs that appear here and in the Komering cloths may derive from the iconography of an older textile tradition, examples of which have not survived.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026