TORAJAN SOCIETY

Torajan society has traditionally been stratified according to age, descent, wealth and occupation and was divided into three classes.Women were prohibited from marrying below their class and using utensils used by slaves, who were considered polluting to people of other classes who touched them. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The three three Torajan classes are: 1) kapua (nobles aristocracy or "big men"), who were semi-monarchical puang in the south and free farmers elsewhere; 2) the tobuda, the unexceptional majority; and 3) kaunan landless slaves. The nobles had the privilege of leadership, as well as the most elaborate house decorations and funerary celebrations. Now, wealthy commoners can enjoy these privileges, too. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The nobility of Toraja are believed to be descendents of heavenly beings who came down by a heavenly stairway to live on earth in the beautiful place where the Torajans live. Slavery is technically illegal but the custom has persisted and is a sensitive topic. Slaves have traditionally been acquired through inheritance. Although they were referred to as "chicken droppings," slaves still had "free souls," and if they played their cards right they could end up richer than their masters. In the old days, young noblemen usually were matched with a slave their own age who attended school and in some cases university with his master. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]]

The Tana Toraja Regency is governed by an official appointed by the Indonesian government and advised by a council of local Torajan representatives. The regency is divided into districts which are made up of of several villages. The Indonesian government provides schools, police, road maintenance, health facilities, post offices and other basic services. Leaders are greatly respected and are chosen on the basis of intelligence, courage, charisma, health and descent. Shaming and gossip are common methods of social control. Disputes are often mediated by kinship house leaders. If that doesn’t work state institutions are sought out. ~

Wealth is greatly admired. The water buffalo is the symbol of Torajan wealth, strength, fertility and prosperity. Buffalo with black and brown spots are worth twenty times more than normal grey ones. At funeral ceremonies when many people are buried hundreds of buffalos are sometimes killed. ♂

RELATED ARTICLES:

TORAJANS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN CULTURE: ART, TEXTILES, MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN RELIGION: AFTERLIFE, PRACTITIONERS, CHRISTIANITY, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN FUNERALS: RITUALS, BELIEFS, COSTS, EVENTS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN BURIALS: TOMBS, TAU TAUS AND THE WALKING DEAD factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA TRAVEL: HOTELS, TRANSPORT, GETTING THERE, RAFTING factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA SIGHTS: TRADITIONAL VILLAGES, HOUSES, CLIFFSIDE GRAVES, FUNERAL SITES factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Torajan Kinship and Village Groups

The Torajan people have strong emotional, economic, and political ties to a number of different kinds of corporate groups. The most basic tie is that of the rarabuku, which might be translated as “family.” Torajan view this grouping as encompassing relations of “blood and bone,” that is, relations between parents and children—the nuclear family. Since Torajans reckon kinship bilaterally, through both mother and father, the possibilities for extending the concept of rarabuku in several different directions are many. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Torajan kinship is organized around “tongkonan” (kindred houses), which contrasts with the banua (ordinary house). The tongkonan is a group of people who reckon descent from an original ancestor. Tongkonan means "origin house." As kinship is bilateral, along both male and female lines, an individual may belong to several tongkonan, though his or her strongest ties are generally with parents, grandparents, and in-laws.Individuals activate lineage connections when rebuilding a house, staging major rituals, or deciding on inheritances. The portion of an inheritance received by an heir is determined by the number of water buffalo contributed to the funeral. Tongkonan membership includes the right to be buried at the ancestral gravesite. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

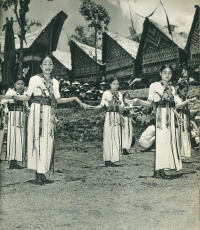

The physical structures belonging to the tongkonan are periodically renewed by replacing their distinctively shaped roofs. This ritual is attended by members of the social group and accompanied by trancelike dances in which the spirits are asked to visit. A third important kind of affiliation is the saroan, or village work group, originally probably an agricultural work group based in a particular hamlet. Beginning as a medium for labor and credit exchange, the saroan has since evolved into a unit of cooperation in ritual activities as well. When sacrifices and funerals take place, groups of saroan exchange meat and other foods. *

The flexibility of these affiliations is partly responsible for the intensity of the mortuary performances. Because there is some ambiguity about one’s affiliation (that is, one’s claims to descent are not only based on blood relationships but also on social recognition of the relationship through public acts), Torajans may attempt to demonstrate the importance of a relationship through elaborate contributions to a funeral, which provides an opportunity not only to show devotion to a deceased parent but also to claim a share of that parent’s land. The amount of land an individual inherits from the deceased might depend on the number of buffalo sacrificed at that person’s funeral. Sometimes people even pawn land to get buffalo to kill at a funeral so that they can claim the land of the deceased. Thus, feasting at funerals is highly competitive. *

Torajan Families

Most households are nuclear families, with cousins, aunts, uncles and grandchildren being regular overnight visitors. Household members are expected to do their share of family chores. Emphasis is placed on hard work, respect for elders. Family needs are placed in front of individual needs. Surviving children and grandchildren inherit property but need to sacrifice a water buffalo at the funeral to claim their inheritance rights. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Men and children usually take care of the water buffalo while women feed pigs. Both men and women fish and work in the fields. Women take care of most the child rearing and household duties but men help with the cooking and caring of babies. Children are raised by both parents and siblings. Adoption among friends and relatives is common, with children often moving back and forth between the homes of the adoptive parents and biological parents.

After a child is born, the father buries the placenta, the child's "twin," in a woven reed bag on the east side of the house. Because many placentas are buried there, a house should never be moved. Torajan children refer to all men and women as "father" and "mother." There is no such thing as a "bastard" or a "broken home." Torajan children sometimes tie a string around a bee and keep it as a pet.~

Torajan Marriage and Sex

Marriage in most cases is monogamous and although some wealthy families practice polygamy. In the past most marriage were arranged. These day many are love matches. Marriages between first and second cousins are taboo although some wealthy families pay a fine to get around this prohibition so they can keep wealth in the family. Marriage tends to last for a long time although it may be dissolved at any time when either party wishes it. Divorce payments are arranged through Torajan versions of pre- nuptial agreements.

Weddings are less elaborate than funerals, requiring only the slaughter of pigs and chickens for the feast rather than the sacrifice of water buffalo. Among the Eastern Toraja the marriage ceremony consists of a festive procession in which the groom travels to the bride's house. During this procession, the groom delivers the “aoe-papitoe” — seven objects that form the basis of the bride price. Afterwards, everyone enjoys a joint meal. The bride price is paid by the groom's family to the bride's relatives, but it cannot exceed what was paid for the bride's mother. Until the bride price is paid, however, any children born to the couple belong to the mother. [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone,e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

Newlywed couples generally lives with the wife's family. Early ethnographies reported that divorce was easy and that premarital sex was common. If a child was born out of wedlock, the father was obliged to marry the mother. After a divorce, the husband had to leave the house, though he could keep the rice barn. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Torajans begin having sex at an early age and most young Torajan men and women have several partners before they get married. According to Torajan tradition any girl who is in the mood for love can take a walk in a rice paddy alone and scream loudly until a suitor arrives and wrestles her to the ground. Some children are given nicknames which elude to their sexual prowess: ""tall bamboo," "granite penis," or "twelve times" for boys and "slippery eel" or "downy bird nest" for girls. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York ♢] .

Torajan Villages

The Torajan people have traditionally lived in isolated mountaintop settlements presumably for defensive purposes but under the Dutch they were encouraged to move into the valleys to make administering them easier. Torajan villages are awesome sights. They are made of clusters of huge four-story-high bamboo rice granaries, plaited bamboo houses and kindred houses. The granaries are organized in rows across from the houses and look like a row of arks ready for the next flood. They are constructed of wood and have deck are where people socialize and receive guests and often have elaborate stylized motifs. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

The Torajan homeland of Tana Toraja lies in the mountainous interior of South Sulawesi, a region long isolated from the dominant lowland peoples—the Islamic Bugis and Makassarese. Traditionally, Torajan families lived in scattered settlements and maintained social ties through ritual exchange rather than centralized political authority. This situation changed in the early twentieth century, when Dutch colonial forces incorporated the highlands into a single administrative unit and forced the Torajan people to abandon fortified hilltop settlements and relocate to lowland plains.

Torajan villages are divided into “upper” and “lower” sections, each serving as a ceremonial unit. Poorer residents live in simple bamboo houses, while wealthier families occupy houses raised approximately 2.5 meters above the ground on wooden posts. Many villages also contain Buginese-style houses elevated on stilts and modern cement houses and have a church and school somewhere in the vicinity. Outside the village are rice fields and gardens.

Among the Eastern Toraja, villages were composed of closely related families, and so-called “tribes” were essentially clusters of neighboring villages whose members recognized descent from a common mother village. Village affiliation could be established through the maternal line, paternal line, or through marriage. Traditionally, society was divided into two classes: freemen and slaves, the latter consisting mainly of debtors and war captives. In areas near the Buginese (Makassar) kingdoms, slave status was hereditary. In general, slaves were not treated harshly, and both slavery and head-hunting were abolished by the Dutch in 1905. [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

Before sustained outside contact, settlements were located near lakes and rivers but were placed on fortified hilltops and mountain ridges to protect against headhunting raids. Villages were usually occupied only during times of danger; most people lived on their farm plots. Village populations generally ranged from about forty to two hundred people, living in roughly two to ten houses. Each house typically contained four to six nuclear families, though some held as many as sixteen. Certain groups, such as the Onda’e and Lage, built single-family dwellings. Villages consisted of houses arranged without a fixed plan, along with rice barns and a temple. Water sources were usually at the base of the hill, limiting the duration of any siege. Under Dutch administration, Eastern Toraja settlements were relocated to valley floors along roadways.

Torajan Houses

Traditional kindred houses are called “tongkonan”. They are central to Torajan social and ritual life and are built through extended family cooperation. There are three main types: the tongkonan layuk, which functions as the highest ritual and political center; the tongkonan pekamberan, associated with families holding local authority; and the tongkonan batu, used by ordinary families. Access to tongkonan was formerly restricted to the nobility, but economic migration and remittances have enabled many commoners to build large and elaborate tongkonan. [Source: Wikipedia]

Some say traditional Torajan houses represent buffalo heads and horns, other suggest suggests they represent the ships the Torajan people use to come to Sulawesi. Other still say they are "space arcs" from another planet. Torajan houses are oriented towards the north, because their ancestors are thought to have come from there, and are shaped like boats to symbolize the boats they arrived in. They have a small plaza for ritual purposes and often decorated in elaborate motifs, with the number of motifs representing the wealth and prestige of the occupant. The Torajans decorate their houses with images of buffalos and cocks. The buffalos are a symbols of prestige and the cocks are messengers to the afterlife. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Traditional Torajan houses are supposed to be possessed only by upper-class families. They are not simply dwellings; they are visual symbols of descent. Each one has a unique name related to male and female descendant of two founding ancestors. Families trace their genealogy through particular houses and an extended relationship is noted when Torajans say to each their that, 'our houses meet.'"

Because traditional houses are small and poorly lit, many Torajans today live in concrete Indonesian-style houses or Bugis wooden houses, sometimes incorporating tongkonan-style saddle roofs. As elsewhere in Indonesia, when families move into modern housing—sometimes under government pressure—they often build a ritually consecrated traditional house alongside it. Many Torajans have done so, and some now use architectural forms and carved decorations to assert higher status within local social and ethnic hierarchies. Many people live in wooden bungalows perched on stilts. Construction of a tongkonan is initiated with the sacrifice of buffalo, pig or chicken and its completion is celebrated with a large feast with more sacrifices. The Tongkona always face a line of rice barns. There are also platforms for sitting and meetings. Certain places are reserved for people of high status.

Traditional Torajan houses continue to be built and lived in and are not just built for tourists. In many case though the owners of “tongkonan” live in modern style homes and keep their traditional homes for ceremonies. Some Torajans maintain their tongkonan, which are unoccupied yet still serve as the symbolic center of family, ethnic, and class identity Torajan artists have developed new styles of carved panels and paintings that call for peace among religious and ethnic communities, including Christians, Muslims, and Chinese Indonesians. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Torajan Food and Clothes

Torajan cuisine tends to be simpler than that of their lowland neighbors. Rice is the preferred staple, but because it is expensive, the poor supplement their diet with maize and tubers. Meat, such as water buffalo, pig, chicken, and, less frequently nowadays, dog, is mostly reserved for feasts. Rice and other food have traditionally been cooked inside a tube of bamboo that is placed in a fire. Carp and eels raised in fish ponds in rice fields are eaten as are sea fish that are brought from the coast on the backs of motorcycles. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

“Papiong” is a dish made from meat, vegetables, and coconut milk stewed in a bamboo tube. “Parmerasan” (buffalo meat cooked in a black sauce) is another favorite. Other Torajan specialties include songkolo (glutinous rice mixed with chili and coconut milk), and baje (fried coconut mixed with brown sugar). Balok, a popular palm wine carried in bamboo tubes, ranges in taste from sweet to sour and is red in color due to a bark extract. Common Torajan sweets include “kacang goreng” (peanuts and treacle wrapped in corn leaves); “kue baje” (sticky rice and palm sugar), and “kue deepa” (rice flour cakes).

The alcoholic drink of choice for the Torajan people is “balok”, fermented sugar palm juice also known as tuak or toddy. The juice is sold to distributors in five foot tubes of bamboo. Vendors sell it in thin short tubes. When a palm tree produces fruit the stem is pierced . A receptacle catches the sap as it flows out. The sap ferments naturally and produces wine. Balok comes in various strengths and different colors (dark red is achieved by adding bark). The wine has to be consumed quickly. It generally isn’t any good after one day.

Torajan everyday dress follows the Indonesian pattern of alternating between sarongs and Western-style clothing, such as trousers. For ceremonial occasions, women wear long, solid-colored (dark red, green, etc.), short-sleeved dresses with beaded belts, headbands, necklaces, and other jewelry. During ceremonies Torajan men sometimes have a kris (traditional dagger) tucked in the back of their sarong. Women wear colored dressed with beaded decorations hanging from their waist and shoulders.

Torajan Work

Most Torajans are subsistence farmers. Rice is the primary crop. It is usually grown in terraced paddies and planted and harvested by hand, with water buffalos used as plow animals. Maize, chilies, beans, yams and potatoes are grown for consumption. Snails. eels and small fish are gathered from the paddies. Coffee, cocoa and cloves are grown as cash crops. Domestic animals include pigs and chickens and water buffalo. Some Torajans supplement their incomes by making wood carvings for tourist or for rituals. Other crafts include knife forging, pottery making and hat plaiting.

Education has enabled many Torajans to become bureaucrats, soldiers, business owners, and scientists, most of whom are employed outside their homeland. Migrants, known for their energy and ambition, include mechanics and shoemakers, as well as furniture makers. The Torajan people enjoy a high reputation for these occupations in eastern Indonesian cities. The many Torajan domestic servants in Makassar city are less esteemed, as the Bugis and Makassar people point to them as evidence of the "natural servility" of the Torajans. The Torajan region was once the main source of slaves for the lowlanders. Tourism has created new employment opportunities as guides, hotel and restaurant staff, and craft makers and sellers. ^ [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Like the Minangkabau and other Indonesian groups, Torajans practice rantau, the custom of labor migration. Many young men leave Tana Toraja to work in cities across Sulawesi or elsewhere in Indonesia. Remittances sent home have significantly increased local wealth, reinforcing traditional practices. Families often invest this income in maintaining or rebuilding tongkonan and financing major ceremonies, allowing Torajans to benefit simultaneously from modern economic opportunities and customary obligations. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Torajan Economic Activity

Village markets are held on six-day cycles. Women usually sell fruit and vegetables. Men sell livestock and palm wine and metal goods. Most villages have a few tiny stores that sell things like cigarettes, soap, instant noodles and sweets. Water buffalo have traditionally been a sign of wealth and are raised for war and sacrifices. Pigs and chicken are also killed for ritual purposes but buffalos carry the most prestige. The wealthy are defined by how many buffalos they own. Land can be purchased with buffalos.

Because of the difficulty and expense in carving new rice terraces from the mountains, rice fields are greatly valued. Most court cases in Torajan areas involve land disputes. The shortage of land has driven many Torajans to the cities and far away provinces in search of work. Among the Eastern Toraja, land had clearly defined boundaries, and each “tribe” (a group of neighboring villages) controlled its own territory for allocation. Each village used as much land as necessary for subsistence and moved to another area within the tribal territory when the soil became exhausted. Land for cultivation was distributed annually to families. These families retained certain rights to land they had cleared outside the tribal territory. Virgin forest, known as pangale, was open to all for hunting, gathering, or cultivation, although it was considered prudent to secure the cooperation and goodwill of neighboring tribes through small gifts. Tribes could also acquire land through purchase or gift.[Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone,e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

Coffee, especially the fine local Arabica variety, has been an important export crop since the mid-19th century and is now joined by pepper and cloves. Torajan coffee is justifiably famous. Rich arabicas are grown in the misty mountains and fetch very high prices. Arabicas are grown mainly for export. Locally, coffee is sometimes roasted with ginger, coconut an even garlic as a flavoring. In coffee-growing areas there are quite few satellite dishes in villages.

Since the 1970s the Torajan area has attracted large numbers of international tourists drawn by its dramatic architecture and elaborate rituals. Since the 1990s, Torajans became a kind of cultural spectacle, as visitors arrived in busloads to witness their funerals and ceremonial pageantry. Tourism strengthened local pride in Torajan identity and stimulated renewed investment in ritual life and house construction.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

In 1985, the South Sulawesi provincial government designated several Torajan villages and burial sites as tourist zones, imposing restrictions on local control over tongkonan and graves. Some Torajan leaders opposed these measures. In 1987, villages such as Kété Kesú temporarily closed to tourists but reopened after a few days because of economic dependence on tourism-related income. [Source: Wikipedia]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026