GEOGRAPHY OF SOUTHERN SULAWESI

Sulawesi is a huge crab shaped island east of Borneo and Kalimantan, south of the Philippines, west of the Moluccas and north of Flores. Formerly known as Celebes, it is about the size of Nebraska and consists of four large peninsulas fringed by coral reefs and covered by large wildernesses areas with marshy coastal plains and jungle covered mountains in the interior. There are also smoking volcanoes and large agricultural areas. Off the coast in some places are distinctive Sulawesi fishing platforms.

South Sulawesi province has a highly varied physical landscape shaped by its position within Sulawesi’s distinctive “K-shaped” form. The province includes low-lying coastal plains along the western margin and increasingly elevated terrain inland, where volcanic and metamorphic highlands form steep hills and dramatic valleys. To the east lies the Gulf of Bone, while offshore islands, including the Selayar archipelago, are an integral part of the province’s geography. Major river systems drain into basins such as the Sengkang Basin, which contains a combination of fluvial, lacustrine, and deltaic environments.

South Sulawesi is bordered by the Makassar Strait to the west and the Flores Sea to the south. Its tropical climate, fertile volcanic and metamorphic geology, and extensive river systems—most notably the Sengkang Basin—support dense forests and productive agricultural land. Geologically, the region reflects a complex tectonic history. It contains magmatic arcs, metamorphic belts, and ophiolite complexes that record the collision and accretion of crustal fragments over millions of years.

South Sulawesi experiences a tropical climate marked by high temperatures and humidity, with a pronounced wet season from November to April and a drier period during the rest of the year. Vegetation varies by elevation and landform, with dense upland forests dominated by teak, pine, rattan, and oak, while river valleys and lowlands support grasses, bamboo, and extensive agricultural cultivation.

The topography of Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula is highly varied, ranging from steep limestone mountains in the north to a broad central plain—its lakes marking the remnants of a former shallow sea—and continuing southward into a chain of volcanic mountains. The heaviest monsoon rains fall in December and January, while the hottest and driest season occurs between June and August. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS ON SOUTHERN SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF SOUTHERN SULAWESI: LIFE, SOCIETY, BOATS factsanddetails.com

SOUTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTH EAST SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR HISTORY, GOWA, TRADE, RELIGION AND SIRI (HONOR) factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR CITY AND REGION factsanddetails.com

BUGIS: LANGUAGE, HISTORY, RELIGION. ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com

BUGIS LIFE AND CULTURE: SOCIETY, FAMILY, FIVE-GENDERS factsanddetails.com

BUGIS SAILING TRADITIONS: SHIPS, PIRACY, WHALE SHARKS factsanddetails.com

TORAJA: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

People of Southwestern Sulawesi

Approximately 1.5 million Makassarese—Indonesia’s thirteenth-largest ethnic group—inhabit the southernmost coastal and mountainous areas of Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula , as well as Selayar and other offshore islands, and a small stretch of fertile lowland north of Makassar city. To their north live around five million Bugis, the country’s eighth-largest ethnic group. The Bugis population extends into the northern highlands and dominates the peninsula’s central lowlands, which form eastern Indonesia’s most productive rice-growing region. Although linguistically closer to the Sa’dan Toraja, the Massenrempulu of the northern highlands and the Luwu people at the head of the Gulf of Bone are usually classified as Bugis due to their adherence to Islam. The Mandarese, numbering about 500,000, occupy the mountainous western bulge of the island and constitute roughly half of the population of West Sulawesi Province, which was administratively separated from South Sulawesi in 2004.[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Beyond Sulawesi itself, Bugis communities—and to a lesser extent Makassarese—are widely dispersed along the coasts of eastern Indonesia. Bugis migrants have traveled as far as the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and northern Australia, and have established long-standing settlements in Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and the cities of Java. According to the 2000 census, Bugis made up 42 percent of South Sulawesi’s population and formed the second-largest ethnic group in several other provinces: 19 percent in Southeast Sulawesi, 14 percent in Central Sulawesi, and 18 percent in East Kalimantan.

More recently, an opposing migratory trend has affected regions such as Luwu and Polewali Mamasa, east of the Mandar area, where transmigrants from Java, Bali, and Lombok have increased ethnic diversity. Makassar has long been a multiethnic city—a reality reflected in its official name, Ujungpandang, from 1971 to 1999. In addition to Makassarese, Bugis, Mandarese, and Toraja, its population includes Chinese, Javanese, Minahasans, Ambonese, and representatives of nearly every ethnic group in eastern Indonesia.

Although most people in the southwestern peninsula of Sulawesi traditionally earned their livelihood from wet-rice cultivation, its Muslim populations have long been renowned throughout the Indonesian archipelago as skilled seafarers. They have been active as shipbuilders, traders, pirates, mercenaries, and migrants. While the Bugis, Makassarese, and Mandarese speak mutually unintelligible languages, they share so many cultural traits that Indonesians often group them together under the label “Bugis–Makassar.”

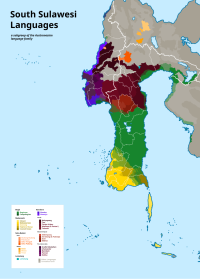

Languages of South Sulawesi

Bugis, Makassar people, Mandar, Sa'dan Toraja, Pitu Ulunna Salo, Seko, and Massenrempulu (Duri) form a distinct South Sulawesi Subbranch within the Western Indonesian Branch of Austronesian languages. Sa'dan Toraja speakers are the closest linguistic relatives of the Bugis, while the speakers of Central Sulawesi languages to the north represent an indigenous population whose occupation preceded that of the South Sulawesi peoples.

Bugis is regionally prestigious and has over 500,000 second-language speakers. Makassar has over 400,000 speakers, though this figure does not include the many ethnic Chinese for whom it is the first language. The multiethnic city of Makassar has long had its own dialect of Malay as its lingua franca. This dialect is distinguishable from the now-common Bahasa Indonesia by its use of sentence-final particles, such as "Satu ji" for "One only" instead of the standard "Satu saja." Personal names generally reflect Islam and are Arabic in origin. Family names are not used.

Bugis and Makassar people share a common script based on an Indic model. In this syllabic script, each of twenty-two symbols stands for a consonant, sometimes prenasalized, plus the inherent vowel a. The five other vowels are indicated by adding diacritics. One further symbol stands for a vowel without a preceding consonant. Writing was developed around 1400, but probably does not derive directly from Javanese kawi.

Early History of Southern Sulawesi

Austronesian-speaking Malay agriculturalists entered Sulawesi from the Philippines approximately 4,000 years ago. Compared with regions farther west, Indian cultural influence was relatively limited, although pre-Islamic burial sites containing Chinese, Siamese, and Annamese porcelain indicate that Sulawesi played an important role as a trading stop on routes to the spice-producing Moluccas.

From as early as the 14th century, South Sulawesi was occupied by kingdoms such as Luwu, Gowa, Soppeng, Tallo and Bone. The first mention of the Makassar is around 1400. At that time there were a number of Makassar principalities, each of which was said to have been founded by a princess or prince who descended from heavenly beings. Islam arrived in 1605. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The earliest kingdoms, first mentioned in fourteenth-century Javanese sources, emerged in eastern Luwu and were initially based on control of iron resources. Over the following three centuries, village confederations developed into monarchies whose rulers claimed divine ancestry through possession of arajang, sacred regalia believed to have descended from heaven.

Gowa Sultanate and the Makassar State

Two Sulawesi kingdoms, Gowa and Tallo, united to form the powerful Makassar state whose hegemony in the early seventeenth century extended well beyond the peninsula, reaching coastal regions of eastern Kalimantan, eastern Sulawesi, and the Lesser Sunda Islands. By the end of the 16th century the twin principalities of Makassar and Gowa, which had been settled by Malay traders and whose commercial realm spread well beyond the region, emerged. In 1607, the explorer Torres met Makassar Muslims on New Guinea.

The Makassar state of Gowa became the most powerful state in Indonesia, outmuscling its rivals the Bugis of southeastern Sulawesi and exerting control over much of what is now eastern Indonesia in the 16th and 17th century. Early European explorers to the region encountered Makassar fleets trading as far east as New Guinea and as far south as Australia. The Makassar were among the first outsiders to have contact with Australian Aborigines, introducing metal tools, pottery and tobacco to them. Gowa endured until it was defeated by Dutch and Bugi forces in 1669.

The Makassar capital, the fortified port of Makassar, attracted Portuguese, Spanish, English, and Danish traders, as well as Malays, Gujaratis, and Chinese merchants seeking to evade the Dutch East India Company’s (VOC) efforts to monopolize the Moluccan spice trade. These expanding contacts facilitated the spread of Islam in South Sulawesi: Luwu converted in 1603, Gowa–Tallo in 1605, and the remaining Bugis kingdoms soon afterward, often following military defeat by Makassarese forces.

Dutch in Sulawesi

European influence started in the 16th century, when in 1538 Portuguese arrived in Makassar and sought audience with Gowa king. Spanish and Portuguese galleons, followed by British and Dutch traders, sailed these seas in search of the spice trade, escorted by their Men of War to protect them from the raids of the Bugis and Makassar pirates.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) viewed Gowa as a threat to its spice monopoly. It allied itself with a Bugi prince to fight them. After a year of fighting the sultan of Gowa was forced to sign the Treaty of Bungaya in 1668 that greatly reduced Gowa’s power and gave the Dutch control of sea lanes and the sources of spices that it wanted.

In 1615, Sultan Alauddin of Gowa famously responded to VOC envoys by declaring, “God made the land and the sea: the land He divided among men, and the sea He gave in common. It has never been heard that anyone should be forbidden to sail the seas.” The VOC ultimately overcame this resistance only by allying with Arung Palakka, a noble from the Bugis kingdom of Bone, who mobilized widespread Bugis resentment against Gowa’s dominance. After the fall of Sultan Hasanuddin’s capital and the rise of a VOC-controlled city on its ruins, political power in South Sulawesi shifted to Bone. Many Makassarese and Wajo Bugis subsequently migrated across the archipelago: Makassarese often joined armed resistance against Dutch rule elsewhere, while Wajo Bugis established ruling dynasties as far away as Johor and Selangor on the Malay Peninsula.

After that the Makassar periodically rebelled and were not brought under Dutch control until 1906 when Dutch forces conquered the interior of their homeland and killed the king of Gowa. Colonialism was only made possible by the incorporation of Makassarese nobles into the colonial system. Even today Makassar nobles occupy many positions of authority in the Indonesian government.

Beyond VOC strongholds in Makassar and along the southern coast, Dutch colonial authority was imposed only in the early twentieth century, following a series of protracted wars between 1824 and 1906; the final Mandar resistance ended in 1916. After three decades of relative stability, Sulawesi came under Japanese naval administration from 1942 to 1945. Although nationalist sentiment had shallow roots, a highly effective guerrilla movement emerged during the violent Dutch counter-revolutionary campaign that followed the Japanese surrender.

Modern History of Southern Sulawesi

Even after the Dutch-sponsored State of East Indonesia, based in Makassar, dissolved itself on 17 August 1950, local strongmen were reluctant to relinquish power to the central government. In turn, Jakarta alienated much of the population by abandoning hopes for an Islamic state and limiting regional autonomy. In July 1950, Kahar Muzakkar—a modernist Muslim leader and revolutionary activist—launched an armed rebellion against the central government that continued until his death in 1965.

See South Sulawesi Atrocities INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

Under Suharto’s New Order regime (1965–1998), economic development resumed in South Sulawesi, and a new commercial elite emerged alongside bureaucrats, military officers, university graduates, and Islamic religious leaders, replacing the aristocracy that had lost its political dominance after independence. Despite these advances, South and West Sulawesi have continued to lag behind other densely populated regions such as Java and Bali and have experienced persistently high levels of poverty.

In the final years of the New Order and the immediate post-Suharto period, South Sulawesi experienced a disproportionate share of Indonesia’s collective violence, ranking third nationally in incidents of intergroup or village conflict between 1990 and 2003. Vigilante “popular justice” was also widespread. The riots that devastated much of the Chinese quarter of Ujungpandang (Makassar) in September 1997, during the Asian financial crisis, remain the most notorious example.

In earlier times, South Sulawesi exported rice, livestock, and dried fish to food-deficient regions such as Eastern Kalimantan, Southeast Sulawesi, and the Moluccas. Decades of warfare that ended in the mid-1960s left the province among the poorest in Indonesia. Income remains below the national average but is rising rapidly as the region fulfills its potential as the service and production center of eastern Indonesia. Historically, the Bugis have depended on rice cultivation for their livelihood, but they are now diversifying into coconuts, coffee, cloves, kapok, candlenuts, and tobacco. However, erosion caused by deforestation threatens agricultural expansion. Fishing and collecting sea products, such as sea cucumbers for the Chinese market, are also important occupations, particularly among the Makassar and Mandarese peoples. Unlike certain other groups, such as the Javanese, there is no prejudice against manual labor. What is important in a job is the extent to which one is free from others' commands.

Religion in Southwestern Sulawesi

Virtually all of the Makassar, Bugis, and Mandar peoples Sunni Muslims. They are considered among the strongest believers in the archipelago, comparable in devotion to the Acehnese and Minangkabau peoples. Although Muslim Malay traders had visited the peninsula's ports since at least the 15th century, tradition attributes the initial propagation of Islam to Minangkabau holy men who arrived at the beginning of the 17th century. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Islam as practiced in South Sulawesi often includes elements of the pre-Islamic religion, such as offerings to ancestors and spirits of the sea, earth, and rice (also rendered to Muslim saints), as well as healing, agricultural, house-, and boatbuilding rituals, care for saukang (supernaturally charged places), and a transvestite priesthood (bissu) that cares for the arajang regalia and performs oracles. In the 20th century, modernist Muslims, who considered many local traditions to be idolatrous, worked with considerable success to eliminate them. However, pre-Islamic religious traditions are still observed by the To Lotang of Sidenreng, whom the government has classified as Hindu, and the Amma Towa of Bulukumba, who defend their Muslim identity. ^

The primary Christian ethnic group in South Sulawesi are the Toraja, concentrated in the Tana Toraja highlands, known for their strong Christian identity and unique cultural blend with faith; while other groups like the Buginese and Makassarese are predominantly Muslim, significant Christian communities exist, and smaller Christian populations are found in areas like Mamasa and Lake Poso, with Mongondow and Ratahan in North Sulawesi also being largely Christian. [Source: Google AI]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026