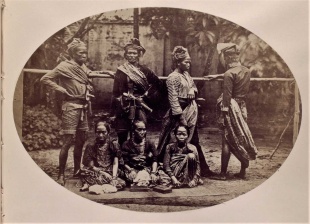

BUGIS SAILING TRADITIONS

The Bugis are famous for their Pinisi-rigged schooners which they have used for centuries to travel as far south as the Australian coast where local people made drawing drawings of their ships and they left behind words that have been integrated in the Aboriginal language of North Australia.

The rhythm of Bugis maritime life is influenced by the monsoon seasons. In part because of their maritime traditions Bugis have settled all across Indonesia. The fiercely independent Bugis have strong notions of autonomy, separate from any nation-state or province. The seafaring Bugis have long traded in slaves, sea products, weapons, and bird's nests for soup. They historically practiced rantau, venturing far away, sometimes migrating permanently. For many of them, their boats have become their only meaningful homes, providing them with a sense of freedom through mobility. Bugis also regard the sea as spiritually potent and make ritual offerings to the aquatic realm before fishing or setting out on a journey.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Bira (150 kilometers southeast of Makassar) is one of the best places to observe Bugis maritime culture and wooden shipbuilding. It is often regarded as one of the last major centers in the world where large wooden vessels are still constructed. In nearby villages such as Marumasa and Tanah Beru, traditional boats of various sizes can be seen at different stages of construction. The area is also known for its brightly painted stilt houses, decorated with images of dragons and flying creatures, as well as for nearby beaches and local wildlife, including pythons.

According to the ancient I La Galigo epic, phinisi-style schooners have been built since at least the 14th century. Today, most phinisi vessels are constructed in Tanah Beru, about 23 kilometers from the town of Bulukumba and roughly 176 kilometers from Makassar. Along its shoreline are numerous dry docks where vessels are carefully crafted using traditional tools and methods passed down through generations. The building of a phinisi is not only a technical process but also a ritual one, as each stage is accompanied by ceremonies believed to ensure spiritual protection and success.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BUGIS: LANGUAGE, HISTORY, RELIGION. ECONOMIC ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com

BUGIS LIFE AND CULTURE: SOCIETY, FAMILY, FIVE-GENDERS factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR HISTORY, GOWA, TRADE, RELIGION AND SIRI (HONOR) factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MAKASSAR CITY AND REGION factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON SOUTHERN SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF SOUTHERN SULAWESI: LIFE, SOCIETY, BOATS factsanddetails.com

SOUTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTH EAST SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

TORAJA: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

Bugis, Piracy and Trade

The Bugis also have a reputation for being pirates. The expression "the boogey man is going to get you", some say, can be traced back to the first Europeans that came to the East Indies who, like everyone else in the region, feared the Bugis. Bugis pirates often plagued early English and Dutch trading ships of the British East India Company and Dutch East India Company. It is popularly believed that this resulted in the European sailors' bringing their fear of the "Bugis men" back to their home countries.

Both Conrad and Melville mentioned the Bugis pirates. Today, Bugis are associated with the rise of piracy in the waters around Indonesia and Southeast Asia. They are thought to be behind some of the pirate attacks in the region. Newspapers have reported Bugis who invaded atolls, burned the villages and made off with an entire year's worth of their cash crop, copra (oil-bearing coconut husks).

Long before European arrived, the Makassarese, Bajau, and the Bugis travelled as far east as the Aru Islands, off New Guinea, where they traded in the skins of birds of paradise and medicinal masoya bark, and to northern Australia, where they exchanged shells, birds'-nests and mother-of-pearl for knives and salt with Aboriginal tribes. Throughout the coastal areas of northern Australia, there is much evidence of a significant Bugis presence. Each year, the Bugis sailors would sail down on the northwestern monsoon in their wooden pinisi. They would stay in Australian waters for several months to trade and take trepang (dried sea cucumber) before returning to Makassar on the dry season off shore winds. Thomas Forrest wrote in A Voyage from Calcutta to the Mergui Archipelago, "The Buginese are a high-spirited people: they will not bear ill-usage...They are fond of adventures, emigration, and capable of undertaking the most dangerous enterprises." [Source: Wikipedia]

Bugis Sailing Ships

Bugis sailing ships are called prahus ((perahus). Described as hybrids between traditional island sailing ships and 17th century Portuguese galleons, they are the last and largest working sailing ships in the world. The co-discoverer of evolution, along with Charles Darwin— Alfred Russel Wallace— wrote in the middle 1800s, "how comparatively sweet was everything on board...no paint, no tar, no new rope (vilest of smells to the squeamish), no grease or oil or varnish; but instead of these, bamboo and rattan and choir rope and palm thatch: pure vegetable fibers, which smell pleasantly, if they smell at all, and recall quiet scenes in the green and shady forest."

Jill Forshee wrote: Bugis invest effort into boats as they would homes. Built of teak or ironwood, some tightly crafted vessels serve as cargo schooners (pinisi). reaching 70 feet in length. These typically carry eight or more people and might boast up to four sails. Elegant, sturdy, and meticulously made, they signify pride and independence. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Measuring up to 150 feet in length, prahus are built in on top of stilts in shallow water just offshore from protected beaches around Bira, Celebes. Deities are consulted about design changes, shamans help pick out the best timbers and nails and screws are not used. Instead the timbers are held together with special wooden pegs that swell when immersed in salt water. Caulking is done with a white cement made by mixing coconut oil and lime from coral over a beach bonfire.[Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

Unlike Middle eastern dhows, the other great sailing trading ship still in use, prahus until fairly recently generally didn't have any kind of inboard or outboard motor, or winches to help pull up the anchor, or motorized pumps to empty water that seeped aboard. They were towed into port with outrigger canoes and barefoot crew members scaled the 75-foot masts on "single frayed and rusted wires" and worked the decks in the open sea without guard rails on the deck, rigging harnesses or ratlines. Some steering was done with oars. A squat toilet was off on the side of the ship. These days may have motors.

Alfred Russel Wallace on Bugis Sailing Ships

On the prahu he traveled in on waters around Indonesia, Alfred Russel Wallace wrote: “It was a vessel of about seventy tons burthen, and shaped something like a Chinese junk. The deck sloped considerably downward to the bows, which are thus the lowest part of the ship. There were two large rudders, but instead of being planed astern they were hung on the quarters from strong cross beams, which projected out two or three feet on each side, and to which extent the deck overhung the sides of the vessel amidships. The rudders were not hinged but hung with slings of rattan, the friction of which keeps them in any position in which they are placed, and thus perhaps facilitates steering. The tillers were not on deck, but entered the vessel through two square openings into a lower or half deck about three feet high, in which sit the two steersmen. In the after part of the vessel was a low poop, about three and a half feet high, which forms the captain's cabin, its furniture consisting of boxes, mats, and pillows. [Source: “The Malay Archipelago” by Alfred Russel Wallace (1869)^]

“In front of the poop and mainmast was a little thatched house on deck, about four feet high to the ridge; and one compartment of this, forming a cabin six and a half feet long by five and a half wide, I had all to myself, and it was the snuggest and most comfortable little place I ever enjoyed at sea. It was entered by a low sliding door of thatch on one side, and had a very small window on the other. The floor was of split bamboo, pleasantly elastic, raised six inches above the deck, so as to be quite dry. It was covered with fine cane mats, for the manufacture of which Macassar is celebrated; against the further wall were arranged my guncase, insect-boxes, clothes, and books; my mattress occupied the middle, and next the door were my canteen, lamp, and little store of luxuries for the voyage; while guns, revolver, and hunting knife hung conveniently from the roof. During these four miserable days I was quite jolly in this little snuggery more so than I should have been if confined the same time to the gilded and uncomfortable saloon of a first-class steamer. Then, how comparatively sweet was everything on board—no paint, no tar, no new rope, (vilest of smells to the qualmish!) no grease, or oil, or varnish; but instead of these, bamboo and rattan, and coir rope and palm thatch; pure vegetable fibres, which smell pleasantly if they smell at all, and recall quiet scenes in the green and shady forest. ^

“Our ship had two masts, if masts they can be called c which were great moveable triangles. If in an ordinary ship you replace the shrouds and backstay by strong timbers, and take away the mast altogether, you have the arrangement adopted on board a prau. Above my cabin, and resting on cross-beams attached to the masts, was a wilderness of yards and spars, mostly formed of bamboo. The mainyard, an immense affair nearly a hundred feet long, was formed of many pieces of wood and bamboo bound together with rattans in an ingenious manner. The sail carried by this was of an oblong shape, and was hung out of the centre, so that when the short end was hauled down on deck the long end mounted high in the air, making up for the lowness of the mast itself. The foresail was of the same shape, but smaller. Both these were of matting, and, with two jibs and a fore and aft sail astern of cotton canvas, completed our rig. ^

“The crew consisted of about thirty men, natives of Macassar and the adjacent coasts and islands. They were mostly young, and were short, broad-faced, good-humoured looking fellows. Their dress consisted generally of a pair of trousers only, when at work, and a handkerchief twisted round the head, to which in the evening they would add a thin cotton jacket. Four of the elder men were "jurumudis," or steersmen, who had to squat (two at a time) in the little steerage before described, changing every six hours. Then there was an old man, the "juragan," or captain, but who was really what we should call the first mate; he occupied the other half of the little house on deck. There were about ten respectable men, Chinese or Bugis, whom our owner used to call "his own people." He treated them very well, shared his meals with them, and spoke to them always with perfect politeness; yet they were most of them a kind of slave debtors, bound over by the police magistrate to work for him at mere nominal wages for a term of years till their debts were liquidated.” ^

Traveling on a Bugis Prahu

Before setting off on a voyage in a prahu an auspicious date is determined by a shaman and astrologers, and a white cock and a black goat are often ritually slaughtered in a "leaving land ceremony," the only time of the year women are allowed to set foot on the deck of a prahu. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

The Bugis follow the monsoons winds east and west, depending on the season. According to the Blair brothers, Prahus are great for traveling down wind, but if they are lightly load they make virtually no progress in an upwind and often times get pushed backwards. Bugis navigators once could navigate by observing wave patterns, seaweed and bird droppings, but now they stick to coast hugging in the belief that in the hope that they could swim to shore if their boat sank. ♢

Prahus have eight large sails and the 12 man crew (including two boys that do most of the work) sleep in cramped quarters below the deck. Lorne Blair wrote in his diary, "Our cabin is barely large enough to accommodate both us and our equipment. We cannot fully stretch out in it, nor sit upright without cracking our heads on the decking above...We share it with an unwelcome assortment of fellow travelers...at night bed bugs crawl out from under our mats, and we listen to cockroaches merrily eating in the food baskets between our heads." ♢

A German doctor, who had spent decades living on Celebes told the Blair brothers, "They like easy trading routes now and they have forgotten old navigation ways. Often they do no go where they are saying. And many sink now every year."

Bugis and Whale Sharks in Triton Bay, Papua

Triton Bay is part of the Bird's Head Seascape, a 225,000 square kilometers epicentre of marine biodiversity off northern Papua in the Indonesian part Papua New Guinea. Here Bugis use floating wooden fishing platforms, called bagans, to catch fish. Whale sharks like to congregate there for fish handouts. Anita Verde of the BBC wrote: The Bugis spend the majority of their lives at sea on their bagans, moving long distances in search of the richest fishing waters. Over generations they have developed an extraordinary relationship with the whale sharks who feed each morning beneath their nets, sucking succulent sardines through the tiny openings. [Source: Anita Verde, BBC, May 27, 2022]

At night, rows of bright lights on the bagans illuminate the water below to attract fish, shrimp and plankton to the fishing nets. However, it was now 06:30 and the lights were dimmed and the nets raised. We approached one of the biggest bagans. A Bugis fisherman named Aching immediately welcomed us on board. He told us that all generations of his family have worked the bagan. In the past, Bugis fished just for themselves and to trade with local communities, but today the scale of industry is much larger, providing fish to local markets and further afield throughout the region. Aching had been fishing through the night and, with his nets now full, he was relaxing in the morning sun.

He gestured to us to peer beneath the platform into the sea. Immediately we glimpsed a colossal, whale shark: the world's biggest fish, as long a school bus. Its size was breath-taking. Aching told us there were actually three whale sharks below his bagan and he had left a net full of small sardines in the water for them to feed on.

Affectionately known by the Bugis as ikan bodo (stupid fish) because of their incredibly gentle and docile nature, whale sharks are revered by the Bugis as harbingers of good fortune. For generations, Aching said, his family has nurtured their relationship with the sharks in the hope that they will be reciprocated with a good catch. Each morning when he lifts his nets, he leaves one in the water for the whale sharks to feed from. "Just the small fish. They only like the small ones," he said.

Interestingly, the belief that the whale sharks bring good fortune is supported by science. "Whale sharks, as well as dolphins, are believed to be good luck because their presence brings important fish such as anchovies, mackerel and tuna to the waters where they feed.

We love the whale sharks. I was taught that they will always bring our family good luck That love has created an interesting migratory pattern. Data from Konservasi Indonesia indicates that while Triton Bay's whale sharks do display migratory patterns, many choose to spend most of their time in the area.

One whale shark, called Dipsy, who was satellite tagged, spent most of its time over a 17-month period in Triton Bay, only briefly visiting the Aru and Kei Islands in the Maluku province of eastern Indonesia. Another, Junior, displayed a clear annual migration over 24 months, feeding in Triton Bay from November through to April, exploring the nearby Arafura Sea and the Timor Gap in May before returning back to Triton Bay in November. Because of this, the Bugis have over time developed unique relationships with the sharks. "It's a bit like they're catching up with old friends every time they pull up their nets," Indra said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026