TORAJAN RELIGION

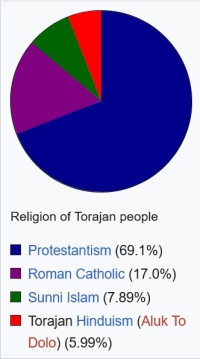

About 69.1 percent of Torajans are Protestant, 17 percent are Roman Catholic, 7.9 percent are . Sunni Muslims and 6 percent follow Aluk To Dolo, the ancestral Torajan belief system that is officially classified as Hinduism. In the 1930s, attacks by Muslim lowlanders contributed to mass conversion to Christianity, partly as a strategy to align with Dutch colonial authority. Further large-scale conversions occurred between 1951 and 1965 during conflict with the Darul Islam movement in South Sulawesi. In 1965, a presidential decree required all Indonesians to adhere to one of the state-recognized religions; in response, Aluk To Dolo was legally recognized in 1969 as a sect of Hinduism (Agama Hindu Dharma). [Source: Wikipedia]

Although only about 6 percent of Toraja officially practice their traditional religion, Aluk Todolo (“Ways on the Ancestors”) it is incorporated onto the belief systems of Christians and Muslims. Many Torajans still associate illnesses with curses and bad spirits and winds in the body. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Since Indonesian independence, Christianity has grown rapidly among the Torajans. Before the 20th century, the Torajans had no separate word for religion, aluk meaning the totality of the correct ways of behaving and working, including those that outsiders would consider secular. The Indonesian state tolerates Aluk To Dolo by classifying it as a variant of Hinduism, one of the recognized five religions under Pancasila. ^[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TORAJAN FUNERALS: RITUALS, BELIEFS, COSTS, EVENTS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN BURIALS: TOMBS, TAU TAUS AND THE WALKING DEAD factsanddetails.com

TORAJANS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, DEMOGRAPHICS, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN SOCIETY AND LIFE: FAMILIES, FOOD, HOUSES, WORK factsanddetails.com

TORAJAN CULTURE: ART, TEXTILES, MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA TRAVEL: HOTELS, TRANSPORT, GETTING THERE, RAFTING factsanddetails.com

TANA TORAJA SIGHTS: TRADITIONAL VILLAGES, HOUSES, CLIFFSIDE GRAVES, FUNERAL SITES factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN SULAWESI: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Traditional Torajan Religion

Traditional beliefs often varied a great deal between Torajan groups. A lack of a written language and physical barriers such as mountains and dense forests resulted in many differences in different groups, Some groups emphasized certain gods, for example, that were ignored by others. Because of the worship of different gods, the Torajan religion was classified as a form of Hinduism by the Indonesian government. Puang Matua is the closest thing the Torajan people have to a supreme God and he was grafted onto the Christian god. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The traditional Torajan religion is called Aluk To Dolo, which means “the ways of the ancestors” or “the beliefs of the old people.” The traditional Torajan religion is called Aluk To Dolo, which means “the ways of the ancestors” or “the beliefs of the old people.” In this belief system, ancestor worship, myth, and ritual are closely connected.

Aluk Todolo blends ancestor worship and animism and is presided over by special priests. The sacred litany for Aluk Todolo begins: "Incline your ear to me, hear what flows from my mouth, For cupped in my hand, I hold the golden breasts of substitute for the ladder to heaven." The old religion is on the decline. Most of its followers are elderly Torajans. Many younger people are Christians. Many believe that Aluk Todolo may be lost within a couple of generations. ~

The traditional Eastern Torajan religion was primarily focused on agriculture and ancestor worship. There were gods of the upper and underworlds, as well as a variety of spirits found in rocks, trees, water, and so on. Many gods and spirits were exclusively associated with agriculture, and each family had its own agricultural spirits. The Eastern Toraja also engaged in secondary death rites, during which the bones of the deceased were cleaned and reburied in caves. After the Dutch gained control of the area, however, these rites were prohibited on sanitary grounds. [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone,e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

Torajan Ancestor Worship

The Torajans believe their ancestors descended to earth from heaven to a mountain top many generations ago. They tell visitors, "Before the dawn of human memory our ancestors descended from the Pleiades in a starship." Their houses, they say, are built to resemble the spaceships that brought them to earth. Ritual sacrifices are made to ancestors who, in turn are expected to protect and provide blessings. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

According to tradition, the first noble ancestor descended from the sky and landed on a mountain, bringing with him the complete social order. This ancestor, called the to manurun, arrived with a house, slaves, animals, plants, and the rules that organized Torajan society. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings]

Along with the to manurun came various religious specialists, including priests (to minaa), the highest-ranking ritual leader (to burake), a rice priest, and a healer. The death priest, however, is not included in these origin stories. Torajan tradition holds that such heavenly descents of noble ancestors occurred several times in the past. Although details vary by region, these core beliefs are shared throughout Tana Toraja.

Torajan Universe

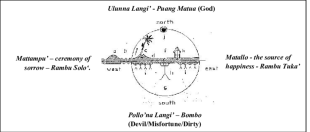

The Torajan universe is divided into three parts, each with its own cardinal direction and rites: 1) the underworld, in the southwest, the home of the dead; 2) the middle-world or earth; and 3) the upperworld, to the north or northeast, the home of deified ancestors. Each is presided over by its own set of gods. Those found on earth sometimes live in particular trees, mountains and other natural objects.[Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The upperworld is ruled by the grandson of the supreme god Gauntikembong, Puang Matua, the creator and the giver of aluk.The middle-world (where humankind lives) is under the jurisdiction of Pong Banggairante. The underworld, associated with the direction South, is governed by Pong Tulakpadang, who has a fearful but not otherwise important wife, Indo Ongon-Ongon. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

While the East is connected to the gods in general, the West is the direction of the spirits of the dead who are specifically believed to reside on Puya, an earthly island far to the southwest. Another god, Pong Lalondong, cuts the thread of life that determines each individual's fate. He guards the peril-fraught path running through the gravestone to Puya. The dead in Puya are sustained by burial offerings. ^^

Torajan Myths, Gods and Spirits

At the beginning of time, heaven and earth were united in darkness and joined in a sacred marriage. When they separated, light appeared, and several gods were born from this union. Puang Matua (“the old lord”) is the chief deity and ruler of the upper world. Pong Banggai di Rante (“master of the plains”) governs the earth, while Gaun ti Kembong (“the swollen cloud”) dwells between heaven and earth. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings]

Indoʾ Belo Tumbang (“the lady who dances beautifully”) is the goddess of healing and medicine, especially invoked in the Maro ritual. Pong Tulak Padang supports the earth, holding it in the palms of his hands rather than on his shoulders. Together with Puang Matua, he maintains balance between night and day and keeps the human world in order.

This balance can be disturbed by Indoʾ Ongon-ongon, the ill-tempered wife of Pong Tulak Padang, who causes earthquakes when angered and is greatly feared. Another feared deity is Pong Lalondong (“the lord who is a cock”). The land of the dead, called Puya, lies beneath the earth to the southwest of the Torajan world.

Both the upper world and the underworld contain many other deities, and additional spirits (deata) are believed to inhabit the earth itself, including rivers, canals, wells, trees, and stones. Eels are especially revered, as they are seen as symbols of fertility. There is a fear of werewolves, spirits that fly at night and spirits that eat the stomachs of sleeping people.

Torajan Views on the Afterlife

The Torajans regard life and death as a continuum and conduct a number of “daluk rampe matallo” (life rituals) and “aluk rampe matampu” (death rituals). The former are sometimes associated with agriculture and fertility rituals with sexual overtones and are also called smoke-rising rites . The latter is visible everywhere, in their graves and funerals, and are called smoke-descending rites. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

According to tradition, the Torajans believe that the dead should be properly sent off to a land called Puya somewhere in the southwest and given enough attention to send them to the upperworld, where defied ancestors live. Most people never make it beyond Puya, where the dead exist a state of being not unlike the life on earth. Those that get lost on the way to Puya and don’t make it may come back and haunt the living so great care s taken to make sure this doesn’t happen.

The Eastern Toraja traditionally believed that tanaona (life force or soul) was able to leave and return to the body at will, chiefly through the top of the head or through the nose and joints. It was thought to reside in various parts of the body, especially the blood, hair, and nails. Death occurred when the tanaona was permanently separated from the body. [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone,e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

Death is something that is always on the mind of Torajans but it something that is viewed as journey one prepares for rather tragedy. Torajan parents make every effort to make sure their infants feet don't touch the ground, with the understanding that if the child died young it would ascend to heaven faster.

Torajan Religious Practitioners and Healers

Traditional ceremonial priests, or to minaa, officiate at most Aluk to Dolo functions. Rice priests (Indo Padang) must avoid death-cycle rituals. In the past, there were also transvestite priests (Burake Tambolang). Minaa are conversant in a special ceremonial language. There are also funerary experts; healers; and heads of the rice cult. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

During major ceremonies, a priest known as the to minaa, who is knowledgeable about Torajan history and traditions, recites long narratives about the origins of the people.These stories explain how the cosmos and the gods were created and how humans, along with their crops and animals, originally came from heaven.

Shamanic traditions varied regionally. Among the Sa’dan Toraja, male homosexual toburake tambolang shamans were known, while among the Mamasa (western Toraja), toburake shamans were female and heterosexual. Among the Eastern Toraja, knowledge of and contact with the gods and spirits were mainly confined to shamans, who were men or women who chose to dress and act like women. Concern with the ancestors was widespread. Shamans (tadu) were primarily healers and were believed to have guardian spirits that they could send to other worlds to retrieve people’s souls and cure illness. Soul loss was regarded as a common cause of sickness. Other religious practitioners with specialized skills also existed, such as those who cured smallpox or made rain; these practitioners were called sando and could be either men or women. Soothsayers and divination specialists (montogoe) played an important role in interpreting the will and guidance of the gods and spirits. Another religious figure was the headhunting leader, the tadulako. Witches and sorcerers were also significant figures in society. [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone,e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

According to Torajan beliefs, illness resulted from punishment by supernatural beings for violating customs, failing to perform offerings or rituals, or from the actions of malevolent forces such as sorcerers, witches, and spirits. When sorcery was involved, sickness was believed to occur either through the theft of a person’s tanoana (life force) or through the insertion of harmful objects into the body. Illness could also be caused by various actions, events, or situations, collectively called measa.

One major form of treatment was the recovery of the patient’s tanoana from supernatural beings. This was carried out by a tadu (shaman), who, assisted by guardian spirits (wurake), traveled to the spirit world. Other healing methods used by sando included chewing medicinal leaves and spitting them onto the patient, or symbolically extracting the object thought to cause the illness. In addition, the Eastern Toraja possessed extensive knowledge of medicinal plants, animals and animal products, and minerals such as salt, which were used in everyday treatments.

Torajan Religious Rituals

The Torajans distinguish between "smoke-rising rituals" (rambu solo), directed to the gods for the benefit of agriculture, and "smoke-descending rituals" (rambu tuka'), dedicated to the welfare of the dead. Smoke-rising rites address the life force, including offerings to the gods and harvest thanksgivings. As Dutch missionaries condemned smoke-rising rituals but tolerated "smoke-descending rituals". [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

"Smoke-rising rituals" include offerings to the gods in paddy fields, at the roadside, and in front of houses. To thank or appease the gods, major animal sacrifices are held every 10 or 12 years on special ceremonial fields, highlighted by the exploding of bamboo stalks in bonfires. Mabugi rites are performed to request rain or deliverance from epidemics; going into trance, participants stab themselves with daggers without harm. Other rites such as the bua' kasalle ensure the welfare of humans, animals, and crops. ^^

By following the rules set by the gods and the ancestors, people fulfill their role in maintaining balance between the upper world and the underworld. This balance is sustained through ritual practice. Rituals of the Rising Sun focus on life, growth, and well-being. These include ceremonies for birth, marriage, rice cultivation, and feasts intended to ensure the prosperity of the family, the house, and the wider community. Healing rituals also belong to this sphere, although illness is seen as a potential threat to social harmony, and therefore healing ceremonies share certain features with rituals of the west. Apart from these exceptions, the eastern and western ritual spheres are kept strictly separate. [Source: Kathleen M. Adams and John Beierle, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The most important ritual of the eastern sphere is the Buaʾ feast, a major ceremony held for an entire territory or ritual community. During this event, the burake—a ritual specialist who may be a priestess or, in some regions, a priest regarded as hermaphroditic—calls upon the gods of the upper world to grant blessings and protection. Another significant ceremony is the Merok feast, held for the welfare of an extended family and centered on the tongkonan, the ancestral house founded by the family’s first ancestor. The most prestigious tongkonan are believed to have been established by a to manurun, a noble ancestor who descended from heaven.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026