HOMININS IN SULAWESI 118,000 YEARS AGO

Archaic humans arrived on Sulawesi — an island in Indonesia just east of Borneo — at least 118,000 years ago, 60,000 years older than previously thought, based on the 2015 discovery of deposit of stone tools and extinct animal bones. Archaeology magazine reported that several hominin species had reached Flores, Java, and Papua by this period, and Sulawesi was assumed to have been part of this dispersal. The new evidence, accumulated over tens of thousands of years, instead points to a long-established population. Because no human fossils have been found, the identity of the hominin species involved remains unknown. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

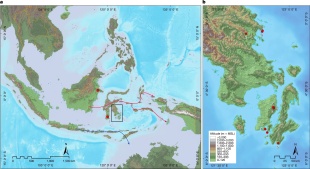

According to the University of Wollongong, humans were long thought to have arrived on Sulawesi between 40,000 and 60,000 years ago. This view changed in 2016, when a team led by Dr Gerrit van den Bergh reported stone artefacts at Talepu, an open-air site on the island’s southwestern arm, dated to more than 100,000 years ago using advanced luminescence techniques. Excavations reached depths of 12 meters and uncovered stone tools alongside fossils of extinct and living megafauna. “It now seems that before modern humans entered the island, there might have been pre-modern hominins on Sulawesi at a much earlier stage,” van den Bergh said, noting that, as on Flores, hominin fossils may yet be found. Van den Bergh first identified the Talepu site in 2007 after a newly cut road exposed stone artefacts in gravel deposits. Early dating attempts were inconclusive. In 2012, colleagues applied a new feldspar luminescence method, MET-pIRIR, which showed that the artefact-bearing sediments were older than 100,000 years. These results were supported by uranium-based dating of fossil teeth from deeper layers. [Source: Bernie Goldie,University of Woolongong, January 14, 2016].

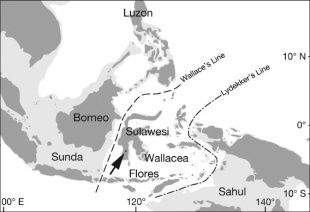

Sulawesi lies within Wallacea, a region of about 2,000 islands separated by deep ocean channels. Early humans entering this area encountered unfamiliar environments with distinctive wildlife. Sulawesi’s terrestrial mammals are almost entirely endemic, and it may have been one of the first places where humans encountered marsupials such as the cuscus. The makers of the Talepu stone tools remain unidentified. The great age of the artefacts suggests they were produced either by an archaic human lineage or, more controversially, by some of the earliest modern humans in Southeast Asia, possibly ancestral to the first people to reach Australia. [Source: Adam Brumm and Michelle Langley, Griffith University, The Conversation, April 3, 2017]

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EAST TIMOR — HOME OF THE WORLD’S FIRST DEEP SEA FISHERMEN factsanddetails.com

FIRST HOMININS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

OLDEST MODERN HUMAN SITES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

LIFESTYLE OF EARLY HUMANS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEAR OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE: PAINTINGS, IMAGES, SPIRITUALITY europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art Hardcover” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com; Doesn't Have Stuff About Sulawesi and Borneo

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com; Doesn't Have Stuff About Sulawesi and Borneo

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Forgotten Exodus: The Into Africa Theory of Human Evolution” by Bruce Fenton (2017) Amazon.com;

“Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond” (Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology) by Christopher J. Norton and David R. Braun Amazon.com;

“Little Species, Big Mystery: The Story of Homo Floresiensis” by Debbie Argue Amazon.com;

“Homo Floresiensis: Diving Deep into our Evolutionary Past” by Austin Mardon, Catherine Mardon, et al. Amazon.com;

“A New Human: The Startling Discovery and Strange Story of the "Hobbits" of Flores, Indonesia” by Mike Morwood, Penny van Oosterzee (2007) Amazon.com;

World's Oldest Rock Art — 67,800 Years Old — Discovered in Sulawesi

In January 2026, archaeologists announced in an article published in Nature that they had identified human-made rock art in a limestone cave on Muna Island, off the southern coast of Sulawesi with a minimum age of 67,800 years, making it the oldest reliably dated human rock art. The art consists of hand stencils with pointed fingers found. It was found in Liang Metanduno, a cave already known to contain ancient rock art.[Source: Michelle Starr, ScienceAlert January 22, 2026 ++]

The reddish hand stencils are faded and barely visible. According to Indonesian and Australian researchers, the stencils were made by blowing pigment onto a hand pressed against the rock surface, leaving an outline. The fingertips were reshaped to appear more pointed. Liang Bua is a well-known cave art site open to tourists. However, most of the art found so far are paintings of chickens and other domesticated animals, which are believed to be much more recent at around 4,000 years old. In 2015, Adhi Oktaviana, an Indonesian rock art specialist and the paper’s lead author, noticed faint images behind more recent paintings that he believed could be hand stencils. [Source: Jennifer Jett, NBC News, January 22, 2026]

The art was dated by dating material on top of the painting. Over long periods, a thin layer of calcite can form over rock art as mineral-rich water flows across cave walls. This water often contains small amounts of uranium, which is soluble in water. Uranium gradually decays into thorium, which is not water-soluble.Because the rate of uranium’s decay into thorium is well known, scientists can analyze the ratio of these elements in the calcite layer to determine when it formed. The mineral crust that formed over the hand stencil artwork was date to be at least of 67,800 years old. ++

Combined with earlier findings, this result suggests that much of the rock art in the region may be significantly older and more widespread than previously estimated."What we are seeing in Indonesia is probably not a series of isolated surprises, but the gradual revealing of a much deeper and older cultural tradition that has simply been invisible to us until recently," archaeologist Maxime Aubert of Griffith University in Australia, who co-led the research, told Science Alert. "The amount and great age of rock art found there show that this was not a marginal or temporary place. Instead, it was a cultural heartland where early humans lived, travelled, and expressed ideas through art for tens of thousands of years." ++

40,000-Year-Old Cave Art in Sulawesi

Rock art and hand prints found in caves in Sulawesi dated to nearly 40,000 years ago were first reported in the mid-2010s. Deborah Netburn wrote in the Los Angeles Times that images discovered in limestone caves on Sulawesi are roughly the same age as the earliest known cave art in northern Spain and southern France. The findings were published in the journal Nature. “We now have 40,000-year-old rock art in Spain and Sulawesi,” said Adam Brumm, a research fellow at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and a lead author of the study. “We anticipate future rock art dating will join these two widely separated dots with similarly aged, if not earlier, art.” [Source: Deborah Netburn, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2014 ~\~]

The Indonesian cave art was first documented by Dutch archaeologists in the 1950s but had not been dated until recently. For decades, researchers believed it dated to the pre-Neolithic period, about 10,000 years ago. “I can say that it was a great — and very nice — surprise to read their findings,” said Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who was not involved in the study. “‘Wow!’ was my initial reaction to the paper… This spectacular finding suggests that the making of images on cave walls was already a widely shared practice 40,000 years ago.”

The unexpectedly early age of the Indonesian paintings points to two possible explanations, the authors wrote. Art may have emerged independently but at roughly the same time in different parts of the world, or it may have been part of an earlier cultural tradition carried by migrating human populations. The findings clearly challenge the idea that Ice Age art was confined to Europe. “The old ‘Europe, the birthplace of art’ story was a naive one, anyway,” Roebroeks said. “We have seen a lot of surprises in paleoanthropology over the last 10 years, but this one is among my favorites.”

As many as 300 caves in the region have been found to contain paintings, making it one of the largest concentrations of early human wall art. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2021]

How the 40,000-Year-Old Suluwesi Cave Art Was Dated

Maxime Aubert of the University of Wollongong, the team's dating expert, and his colleagues dated the Indonesian paintings using calcium carbonate deposits known as “cave popcorn” that formed as mineral-rich water trickled down the cave walls. The deposits contain low levels of radioactive uranium which decays into thorium at a known rate, providing an effective geological clock. The age of cave popcorn that formed on top of paintings gave the researchers a minimum age for the images, while samples from underneath the cave art gave them maximum ages. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, October 9, 2014]

“Dr Aubert told The Straits Times: "When the cave water precipitates on the painting, it also contains a small amount of uranium as well, since uranium is soluble in water. Over time, it starts to decay into an element known as thorium. Thorium is not soluble in water, so the element would not have been present at the point of crystal formation. [Source: Cheryl Tan, Strait Times, January 25, 2021]

Deborah Netburn wrote in the Los Angeles Times that the researchers began their work in 2011 without assumptions about the age of the Sulawesi rock art and aimed simply to establish reliable dates. They used U-series dating, a relatively new method that has also been applied to cave art in Western Europe. The team searched for images covered by small, cauliflower-like mineral growths and identified 14 suitable examples, including 12 hand stencils and two figurative drawings.

Using a rotary tool with a diamond blade, Maxime Aubert removed small samples of the mineral “cave popcorn,” which included traces of the underlying pigment. Because the pigment must be at least as old as the first mineral layer that formed over it, this allowed the researchers to determine minimum ages for the artworks. One hand stencil was dated to at least 39,900 years ago, while a painting of a pig deer was dated to at least 35,400 years ago.

For comparison, the oldest known cave painting in Europe is a red disk from El Castillo Cave in Spain with a minimum age of 40,800 years. The earliest known figurative painting in Europe, a rhinoceros from Chauvet Cave in France, has been dated to 38,827 years ago. [Source: Deborah Netburn, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2014 ~\~]

Artwork in the Sulawesi Caves

The paintings were made with the natural mineral pigment ochre — probably ironstone haematite — which the hunter-gatherers ground to a powder and mixed with water or other liquids to create paint. As of 2014, researchers dated 12 hand stencils and two figurative paintings of animals in seven caves near Maros.

Inside Leang Timpuseng cave, Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Scattered on the walls are stencils, human hands outlined against a background of red paint. Though faded, they are stark and evocative, a thrilling message from the distant past. My companion, Maxime Aubert, directs me to a narrow semicircular alcove, like the apse of a cathedral, and I crane my neck to a spot near the ceiling a few feet above my head. Just visible on darkened grayish rock is a seemingly abstract pattern of red lines. Then my eyes focus and the lines coalesce into a figure, an animal with a large, bulbous body, stick legs and a diminutive head: a babirusa, or pig-deer, once common in these valleys. Aubert points out its neatly sketched features in admiration. “Look, there’s a line to represent the ground,” he says. “There are no tusks — it’s female. And there’s a curly tail at the back.” [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2016]

Researchers have identified two main phases of artwork. Later charcoal drawings depict geometric shapes and animals introduced to Sulawesi in recent millennia. Earlier red and purplish paintings—hand stencils and endemic animals such as babirusa and warty pigs—were dated using uranium-series methods. Results published in Nature in 2014 showed that some of these works are at least 39,900 years old. The youngest dated stencils indicate that this artistic tradition continued for at least 13,000 years with little change.

The hand stencils vary widely in size and form, suggesting participation by adults and children. Some show missing or bent fingers, painted palm lines, or overlapping outlines. Similar practices persist in parts of Indonesia and Australia, where handprints serve symbolic roles tied to protection, identity, or place. Rock art specialists note parallels with Aboriginal Australian stencils, often interpreted as statements of belonging and presence.

Animal Images from Sulawesi

Leang Timpuseng Cave in the Maros-Pangkep karst area also includes some of the most ancient animal paintings. Among them is a depiction of a babirusa or ‘deer-pig’, which are still found in Sulawesi today and were preyed upon by the hunter-gatherers that made the images. “The paintings of the wild animals are most fascinating because it is clear they were of particular interest to the artists themselves,” Brumm told The Guardian. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, October 9, 2014]

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: The hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi, an ancient island that has been called the Madagascar of Indonesia. While most of the animals in the paintings are identifiable, the artists often exaggerated aspects of the beasts, perhaps to accentuate features that interested them, said Brumm. “The feet are usually dainty appendages that were evidently painted with exquisite care, whereas the bodies are huge and bulbous, almost balloon-like in form giving some animal images an otherworldly appearance. In a few cases, the actual ground surface beneath the animals is also depicted, which is very rare worldwide. The paintings are feats of great imagination and they provide the first real insight into the artistic culture and symbolic conventions of early modern humans in Asia.”

The focus on Europe as the origin of art arose after the discovery of occasionally exquisite ancient paintings in caves across the continent. The oldest rock art — a smudged red disk on a cave wall at El Castillo in Spain — was painted at least 41,000 years ago. The breathtaking charcoal drawings of horses and rhinos at the Chauvet caves in the Ardeche in Southern France are at least 30,000 years old.

Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, told The Guardian: “These exciting discoveries allow us to move away from Eurocentric ideas on the development of figurative art to consider the alternative possibility that such artistic expression was a fundamental part of human nature 60,000 years ago, when modern humans not only occupied most of Africa but were beginning to disperse out towards Europe and the Far East. “When modern humans colonised Sulawesi at least 50,000 years ago as a precursor to reaching New Guinea and Australia, they were probably already producing these kinds of depictions. I predict that even older examples of cave art will be discovered on Sulawesi, and in mainland Asia, and ultimately in our African homeland dating to more than 60,000 years ago.”

45,500-Year-Old Pig — Oldest Known Animal Depiction

A well-preserved painting of a pig from the Leang Tedongne cave on Sulawesi may be the oldest known animal image. Dating back 45,500 years, the nearly life-size depiction of a small native warty pig was rendered using red ochre on a rock art panel and appear to be part of a narrative scene. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2021]

According to a report published in Science Advances journal the painting measures 136 centimeters by 54 centimeters (53 inches by 21 inches) and depicts a pig with horn-like facial warts characteristic of adult males of the species. There are two hand prints above the back of the pig, which also appears to be facing two other pigs that are only partially preserved.

Maxime Aubert, the co-author of the report, told the BBC: “It provides the earliest evidence of human settlement of the region. “The people who made it were fully modern, they were just like us, they had all of the capacity and the tools to do any painting that they liked." Aubert used the uranium-series isotope dating technique described above on a calcite deposit that had formed on top of the painting and determined that the deposit was 45,500 years old. Animal paintings found in cave were dated at 44,000 years old “This makes the artwork at least that old. "But it could be much older because the dating that we're using only dates the calcite on top of it," he added. [Source: BBC, January 14, 2021]

“Co-author Adam Brumm said: "The pig appears to be observing a fight or social interaction between two other warty pigs." To make the hand prints, the artists would have had to place their hands on a surface before spitting pigment over it, the researchers said. The team hopes to try and extract DNA samples from the residual saliva as well. The painting may be the world's oldest art depicting a figure, but it is not the oldest manmade art. In South Africa, a hashtag-like doodle created 73,000 years ago and discovered ib 2018, is believed to be the oldest known drawing.

44,000-Year-Old Sulawesi Cave Art — The World’s Oldest Story?

A cave painting from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 4 in southern Sulawesi depicts what may be the world’s oldest known figurative artwork and the earliest narrative scene. Dated to at least 43,900 years ago, the nearly 4.5-meter-wide image shows wild pigs and small buffalo being pursued by small, human-like figures. The discovery, reported in Nature in 2019, suggests a highly developed artistic and symbolic culture during the Upper Paleolithic. [Source: AFP, December 12, 2019]

The hunters are shown with human bodies but animal features such as tails, snouts, or bird- and reptile-like heads, and appear to carry spears or ropes. These therianthropic figures imply an ability to imagine beings that do not exist in nature, a cognitive capacity linked to myth-making and possibly early religious thought. Researchers argue that the scene represents the earliest known example of storytelling in visual art.

Sulawesi contains hundreds of caves with ancient imagery, many still being discovered. The hunting scene went unnoticed for decades because it is located high on a cave wall and was only identified after an archaeologist climbed a tree to reach it. Its age exceeds that of earlier dated animal paintings from Borneo and other Sulawesi sites.

Some scholars, however, question whether the images form a single scene or were created over a long period, noting differences in scale and composition. Others are skeptical that the lines interpreted as weapons clearly represent spears. Despite these debates, researchers agree on the significance of the find and warn that the paintings are rapidly deteriorating as the cave walls flake and erode, limiting the time available for further study.

People Who Made the Sulawesi Cave Art

People first reached Sulawesi as part of the wider human dispersal out of East Africa that began around 60,000 years ago. Moving along coastal routes through the Red Sea, the Arabian Peninsula, and South and Southeast Asia, these early humans eventually reached Borneo, which at the time was connected to the mainland. Sulawesi, however, was always separated by open ocean. Reaching it required purposeful sea crossings of at least 60 miles, likely using simple boats or rafts. Although no human fossils from this early period have yet been found on the island, Sulawesi’s first inhabitants are thought to have been closely related to the people who went on to colonize Australia by about 50,000 years ago. “They probably looked broadly similar to Aboriginal or Papuan people today,” says archaeologist Adam Brumm. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2016]

By tens of thousands of years ago, these early Sulawesians were living in caves and rock shelters across the island. In a site known locally as Mountain-Tunnel Cave, modern excavations are uncovering traces of their daily lives. In a carefully dug trench, Brumm and his team have found evidence of hearths, fire use, and finely made stone tools, likely used in hunting and food preparation. While large animals such as wild boar were sometimes taken, the remains show that the cave’s occupants relied heavily on freshwater shellfish and the Sulawesi bear cuscus, a slow-moving tree-dwelling marsupial.

The cave walls tell another part of the story. Mountain-Tunnel Cave contains hand stencils and widespread traces of pigment, and excavations are now revealing the materials used to make the art. In layers dated to the same period as nearby stencils, Brumm reports a sharp increase in ocher. Stone tools smeared with red pigment, ocher chunks bearing scrape marks, and scattered fragments from grinding and mixing paint have all been found. So much pigment was used that entire layers of sediment are stained deep red.

These occupation layers extend back at least 28,000 years, and older deposits are now being analyzed using radiocarbon dating and uranium-series dating of stalagmites that cut through the sediment. Brumm describes this work as “a crucial opportunity,” because it allows researchers, for the first time in this region, to directly link buried archaeological evidence with rock art on the walls. The findings suggest that cave art was not always a rare or isolated ritual activity. Instead, painting appears to have been woven into everyday life, carried out in the same spaces where people cooked, ate, made tools, and gathered around the fire.

Evidence for Sulawesi’s long artistic tradition extends beyond cave walls. According to Archaeology magazine, two small incised stone artifacts found in Leang Bulu Bettue Cave and dated to between 26,000 and 14,000 years ago demonstrate the production of portable art. One object depicts an anoa, a local dwarf buffalo, while the other bears a sunburst design. Together with the cave paintings, these finds show that early humans in Southeast Asia possessed the capacity for figurative and symbolic expression long thought to distinguish Homo sapiens, filling an important gap in the story of human creativity. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2020]

Discovering the Remarkable Age of the Sulawesi Cave Art

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Aubert, who grew up in Lévis, Canada, and says he has been interested in archaeology and rock art since childhood, thought to date rock formations at a minute scale directly above and below ancient paintings, to work out their minimum and maximum age. To do this would require analyzing almost impossibly thin layers cut from a cave wall — less than a millimeter thick. Then a PhD student at the Australian National University in Canberra, Aubert had access to a state-of-the-art spectrometer, and he started to experiment with the machine, to see if he could accurately date such tiny samples. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2016]

In the meantime, Brumm — an archaeologist at the University of Wollongong, where Aubert had received a postdoctoral fellowship — started digging in caves in Sulawesi. As Brumm and his Indonesian colleagues worked they were struck by the hand stencils and animal images that surrounded them. The standard view was that Neolithic farmers or other Stone Age people made the markings no more than 5,000 years ago — such markings on relatively exposed rock in a tropical environment, it was thought, couldn’t have lasted longer than that without eroding away. But the archaeological evidence showed that modern humans had arrived on Sulawesi at least 35,000 years ago. Could some of the paintings be older? “We were drinking palm wine in the evenings, talking about the rock art and how we might date it,” Brumm recalls. And it dawned on him: Aubert’s new method seemed perfect.

After that, Brumm looked for paintings partly obscured by speleothems every chance he got. “One day off, I visited Leang Jarie,” he says. Leang Jarie means “Cave of Fingers,” named for the dozens of stencils decorating its walls. Like Leang Timpuseng, it is covered by small growths of white minerals formed by the evaporation of seeping or dripping water, which are nicknamed “cave popcorn.” “I walked in and bang, I saw these things. The whole ceiling was covered with popcorn, and I could see bits of hand stencils in between,” recalls Brumm. As soon as he got home, he told Aubert to come to Sulawesi.

“Aubert spent a week the next summer touring the region by motorbike. He took samples from five paintings partly covered by popcorn, each time using a diamond-tipped drill to cut a small square out of the rock, about 1.5 centimeters across and a few millimeters deep. Back in Australia, he spent weeks painstakingly grinding the rock samples into thin layers before separating out the uranium and thorium in each one. “You collect the powder, then remove another layer, then collect the powder,” Aubert says. “You’re trying to get as close as possible to the paint layer.” Then he drove from Wollongong to Canberra to analyze his samples using the mass spectrometer, sleeping in his van outside the lab so he could work as many hours as possible, to minimize the number of days he needed on the expensive machine. Unable to get funding for the project, he had to pay for his flight to Sulawesi — and for the analysis — himself. “I was totally broke,“ he says.

“The very first age Aubert calculated was for a hand stencil from the Cave of Fingers. “I thought, ‘Oh, shit,’” he says. “So I calculated it again.” Then he called Brumm. “I couldn’t make sense of what he was saying,” Brumm recalls. “He blurted out, ‘35,000!’ I was stunned. I said, are you sure? I had the feeling immediately that this was going to be big.”

30,000-Year-Old Jewelry from Sulawesi

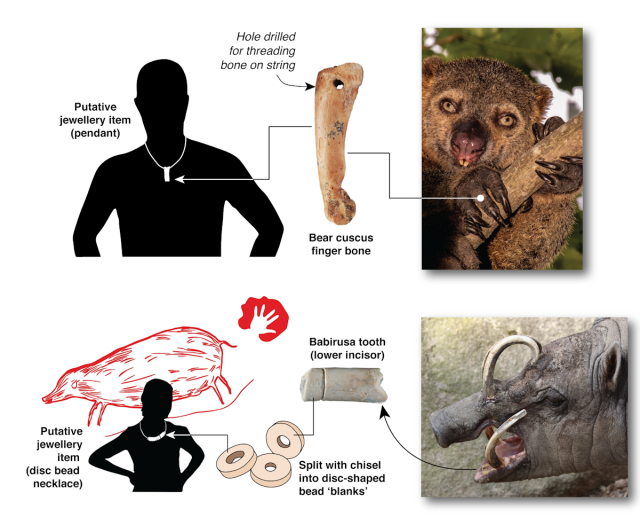

Excavations at the Leang Bulu Bettue cave complex in Sulawesi have uncovered an extraordinary assemblage of Ice Age art and ornaments — including carved images of babirusa and cuscus, engraved stone fragments, and tools decorated with crosses, leaf-like patterns, and other geometric designs — some dating back at least 30,000 years. Using multiple dating methods, researchers determined that the artefacts span roughly 30,000 to 22,000 years ago. Among them are disc-shaped beads made from babirusa tooth and a perforated “pendant” fashioned from the finger bone of a bear cuscus, both animals found only on Sulawesi. [Source: Adam Brumm and Michelle Langley, Griffith University, The Conversation, April 3, 2017]

One notable discovery is a drilled bear cuscus finger bone that shows wear consistent with having been suspended against skin or clothing, indicating it was worn as a pendant or similar item of personal adornment. A fragment of limestone incised with overlapping lines forming a simple crisscross motif appears to be part of a larger, still-missing decorated block. Additional evidence of symbolic behavior comes from abundant traces of rock art production: used ochre pieces, tools stained with ochre, and a hollow bone tube — made from a bear cuscus limb bone and containing red and black pigments — that may have served as an airbrush for creating hand stencils.

All of these finds come from archaeological deposits contemporary with the dated rock paintings in the surrounding limestone hills. Discovering buried evidence of symbolic activity directly alongside Ice Age cave art is rare, and until this work it was unclear whether Sulawesi’s prehistoric painters decorated themselves with ornaments or produced artistic objects beyond wall paintings.

The use of babirusa and bear cuscus bones and teeth in ornaments — combined with the rarity of babirusa remains in food debris and the appearance of these species in art — suggests these animals held special symbolic significance for Ice Age inhabitants. The newcomers may have developed strong spiritual or cultural associations with these strange and elusive creatures.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except of Talepu map from Nature

Text Sources: Archaeology National Geographic, University of Woolongong, The Guardian, AFP, BBC, Los Angeles Times, The Independent, New York Times, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Reuters, Wikipedia, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026