WORLD'S EARLIEST ART

Among the oldest works of modern human art is a piece of red ocher carved with zigzag lines found at Blombos cave in South Africa and dated to about 100,000 years ago. Similar zigzag markings were made on a shell found in Indonesia dated to 540,000 years ago presumably made by homo erectus.

Rock cupules are artificially made depressions on rock surfaces that resemble the shape of an inverse spherical cap or dome. They were made by direct percussion with hand-held hammer-stones, on vertical, sloping or horizontal rock surfaces. Cupules are widely believed to be the world's most common rock art motifs. They have been found on almost every continent and were produced by many cultures. It's not known what, if anything, the carved pits or cups represent, but archaeologists think the earliest may be 1.7 million years old. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2024; Wikipedia]

Smriti Rao of Discover wrote: Archaeologists working in Blombos Cave in South Africa found engraved red ochre, incised bone and pierced shells that were strung and presumably worn on the body—all from layers dated to 75,000 years ago; three shell beads from Israel and Algeria are said to date to more than 100,000 years ago; dozens of pieces of red ochre–many of which were ground for use as pigment–turned up in layers dating to 165,000 years ago in a cave at Pinnacle Point in South Africa [Scientific American].” Scientists debate wether these early engravings and body decorations were produced for aesthetic purposes or were a form of symbolism. [Source: Discovery News, Smriti Rao, Discover, March 3, 2010 /^]

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ; Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org; Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net; Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008) Amazon.com;

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist Amazon.com;

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art (World of Art)” (2017) by Bruno David Amazon.com;

“Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe” by Paul Bahn Amazon.com;

“Images of the Ice Age” by Paul G. Bahn Amazon.com;

“The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art” by David Lewis-Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

“Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne” by Christine Desdemaines-Hugon (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs” by Mario Ruspoli (1987) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave” by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps (1996) Amazon.com;

“Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times” by Jean Clottes (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Altamira” by Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, Frederico Bernaldo de Quiros (1999) Amazon.com;

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WHY EARLY HUMANS MADE ART factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: ANIMALS, HAND PRINTS, FIGURES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE: PAINTINGS, IMAGES, SPIRITUALITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE DISCOVERY, STUDY, FILMING europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST SCULPTURES factsanddetails.com ;

VENUS STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST POTTERY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST MUSIC: FLUTES, NEANDERTHALS. LITHOSPHONES europe.factsanddetails.com

Types of Early Human Art

The oldest things produced by early hominins that might qualify as art are carefully-crafted stone tools and spheres (See Below). Among these are 240,000-year-old blades made from long slivers of difficult-to-work lava from the Rift Valley in Kenya as well as beautifully-carved 90,000-year-old bone harpoon used to hunt giant catfish in present-day the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formally Zaire).

Some ocher sticks, dated to 77,000 years ago, have also been found in Blombos Cave near Capetown, South Africa. Made of red ocher mudstone, they have scratchings on them, widely recognized as art. One polished stone contains a geometric design consisting of crosshatching framed by two parallel lines with a third line down the middle. Some anthropologists regard them as the oldest known expressions of art and creativity. Inscribed ostrich shells dated to 60,000 years ago have been found at the Diepkloof site in South Africa

Delicate shell beads, dated to 75,000 years ago, have been found in Blombos Cave. The beads are made from tiny shells that have holes pierced in them, presumably so they could be strung together. They are considered art because they had no real practical utilitarian usage. It has been suggested that were jewelry or clothes decoration (or possible a kind of abacus, which would make them a tool).

Christopher Henshilwood, the leader of French, British and Norwegian team that found the beads, said: “These bead are symbolic and symbolism equates with modern human behavior. Perhaps they were used for painting and body ornamentation." Henshilwood is an archaeologist at Norway's University of Bergen and the University of Witwterstand in South Africa," Blombus Caves is not far from a large swath of property owned by his grandfather. Henshilwood's team also found the ocher sticks.

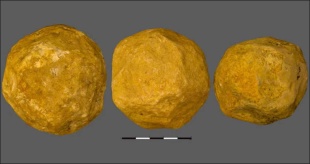

Mysterious 2 Million-Year-Old Deliberately-Made Stone Spheroids

In September 2023, scientists announced that early hominins deliberately made stones into spheres 1.4 million years ago in Israel, though what prehistoric people used the balls for remains a mystery. AFP reported: Archaeologists have long debated exactly how the tennis ball-sized "spheroids" were created. Did early hominins intentionally chip away at them with the aim of crafting a perfect sphere, or were they merely the accidental by-product of repeatedly smashing the stones like ancient hammers? New research led by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem suggests that our ancestors knew what they were doing.

“The team of scientists examined 150 limestone spheroids dating from 1.4 million years ago which were found at the 'Ubeidiya archaeological site, in the north of modern-day Israel. Using 3D analysis to reconstruct the geometry of the stones, the researchers determined that their sphericalness was "likely to have been produced intentionally". The early hominins — exactly which human lineage they belonged to remains unknown — had "attempted to achieve the Platonic ideal of a sphere", they said. While the spheroids were being made, the stones did not become smoother, but did become "markedly more spherical," said the study in the journal Royal Society Open Science. This is important because while nature can make pebbles smoother, such as those in a river or stream, "they almost never approach a truly spherical shape," the study said. [Source: AFP, September 6, 2023]

Julia Cabanas, an archaeologist at France's Natural History Museum told AFP that this means the hominins had a "mentally preconceived" idea of what they were doing. That in turn indicates that our ancient relatives had the cognitive capacity to plan and carry out such work. Cabanas said the same technique could be used on other spheroids. For example, it could shed light on the oldest known spheroids, which date back two million years and were found in the Olduvai Gorge of modern-day Tanzania. But exactly why our ancestors went to the effort of crafting spheres remains a mystery. Possible theories include that the hominins were trying to make a tool that could extract marrow from bones, or grind up plants. Some scientists have suggested that the spheroids could have been used as projectiles, or that they may have had a symbolic or artistic purpose. "All hypotheses are possible," Cabanes said. "We will probably never know the answer."

According to Live Science: A recent study analyzed the stone spheroids mathematically and suggested they were attempts to impose spherical "symmetry" on roughly round balls of rock. The researchers didn't call these "art," but they noted that some ancient hand axes also show symmetry [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2024]

Earliest Known Engraving — from 540,000 Years Ago

A zigzag pattern found on the fossilised shell, dated to 430,000 years ago, in Java, Indonesia is believed to be the world’s earliest known engraving. It is thought to have been by homo erectus, demonstrating the species manual dexterity and perhaps symbolism and art. Australian Associated Press reported: “The find, reported in the journal Nature on Thursday, predates by some 300,000 years other markings made by modern humans or Neanderthals, previously thought the oldest. The age and location of the shell suggests the pattern was carved by an even earlier human ancestor known as Homo erectus. “It rewrites human history,” said Dr Stephen Munro, the Australian National University paleoanthropologist who made the find. [Source: Australian Associated Press, December 3, 2014]

“It suggests Homo erectus had considerable manual dexterity and possibly greater cognitive abilities, and raises the prospect that they might have been more “human” than previously thought. “That’s something people will argue about,” Munro said. Munro then worked with international colleagues to accurately date the shell and to check that the engraving wasn’t a more recent addition. They found that the engraving was indeed made before fossilisation occurred, probably between 430,000 and 540,000 years ago. It’s unclear whether the pattern was intended as art or served some other purpose.

“The ancient find would have been impossible without the very modern technology of digital photography. The shells, first discovered by celebrated Dutch scientist Eugene Dubois a century ago, have been packed away in boxes for years. On a Dutch public holiday in May 2007, Munro seized the opportunity to photograph every one. It took him all day. When he returned to Australia and flicked through the photos, one in particular stood out. An engraving, all but invisible to the naked eye, was quite clear. “It was a eureka moment,” he said. “I could see immediately that they were man-made engravings. There was no other explanation.”“

Early Art from Africa, the Middle East, Homo Heidelbergensis and Neanderthals

Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “Nassarius beads have been dated to 82,000 years ago at a site called Grotte des Pigeons (Pigeon Cave) in Taforalt, Morocco. At the opposite end of the Mediterranean, similar beads from two Israeli caves, Qafzeh and Skhul, were dated to 92,000 and at least 100,000 years ago. Back in South Africa, a 2010 team led by the University of Bordeaux’s Pierre-Jean Texier reported finding 60,000-year-old engraved ostrich eggshells in Diepkloof Rock Shelter north of Cape Town. [Source: Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

“Compared with the jaw-dropping beauty of the art created in Chauvet Cave 65,000 years later, artifacts like these seem rudimentary. But creating a simple shape that stands for something else—a symbol, made by one mind, that can be shared with others—is obvious only after the fact. Even more than the cave art, these first concrete expressions of consciousness represent a leap from our animal past toward what we are today—a species awash in symbols, from the signs that guide your progress down the highway to the wedding ring on your finger and the icons on your iPhone.

“There’s something else telling about these early African and Middle Eastern eruptions of symbolism: They come, and then they go. The beads, the paint, the etchings on ocher and ostrich egg—in each case, the artifacts show up in the archaeological record, persist in a limited area for a few thousand years, and then vanish. The same applies to technological innovations. Bone harpoon points, found nowhere else before 45,000 years ago, have been uncovered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in sediments nearly twice that old. In South Africa two relatively complex stone and bone tool traditions appear—the Still Bay 75,000 years ago and the Howieson’s Poort 65,000 years ago. But the latter lasted just 6,000 years, the former 4,000. Nowhere has a tradition been found to spread across space and through time, gathering richness and diversity, until just before 40,000 years ago, when art began to appear more commonly across Africa, Eurasia, and Australasia. As far east as the Indonesian island of Sulawesi (Celebes), stenciled handprints—once thought of as an invention of the European Upper Paleolithic—were recently shown to be almost 40,000 years old.

Homo heidelbergensis, hypothesized to be the ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals, is generally estimated to have lived from around 600,000 years ago to 300,000 years ago. Modern humans are well known for producing etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value after this time. As of 2018, only handful of objects with postulated to have symbolic etching, predate 200,000 years ago. Among these are: 1) a 400,000 to 350,000 years old bone from Bilzingsleben, Germany; 2) three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; 3) a 250,000-year-old pebble from Markkleeberg, Germany; 4) 18 roughly 200,000-year-old pebbles from Lazaret (near Terra Amata); and 5) a roughly 200,000-year-old lithic from Grotte de l'Observatoire, Monaco. [Source: Wikipedia]

Examples of Neanderthal art that have been found include perforated and grooved animal teeth, and ivory rings. A carved and polished ivory tooth from a baby mammoth, and elk and wolf teeth with holes that may have been worn as pendants were found in a French cave near Arcy-sur-Cure. It seems likely that Neanderthals may have made art such a carved wood or created rituals dance or produced some other kind of art that has are not been preserved. In 2021, scholars writing for the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, described an engraved giant deer phalanx, at least 51,000-year-old, at the former cave entrance of Germany's Einhornhöhle. They argued the engraved bone "demonstrates that conceptual imagination, as a prerequisite to compose individual lines into a coherent design," existed in Neanderthals.

See Separate Articles: HOMO HEIDELBERGENSIS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, HUNTING, MURDER, ART factsanddetails.com ; NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEAR OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com

Where Did the First Art Arise

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The discovery of beautiful 45,000-year-old art in Sulawesi, Indonesia “obliterated what we thought we knew about the birth of human creativity. At a minimum, they proved once and for all that art did not arise in Europe. By the time the shapes of hands and horses began to adorn the caves of France and Spain, people here were already decorating their own walls. But if Europeans didn’t invent these art forms, who did? [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2016]

“On that, experts are divided. Paul Taçon, an expert in rock art at Griffith University, doesn’t rule out the possibility that art might have arisen independently in different parts of the world after modern humans left Africa. He points out that although hand stencils are common in Europe, Asia and Australia, they are rarely seen in Africa at any time. “When you venture to new lands, there are all kinds of challenges relating to the new environment,” he says. You have to find your way around, and deal with strange plants, predators and prey. Perhaps people in Africa were already decorating their bodies, or making quick drawings in the ground. But with rock markings, the migrants could signpost unfamiliar landscapes and stamp their identity onto new territories.

“Yet there are thought-provoking similarities between the earliest Sulawesian and European figurative art — the animal paintings are detailed and naturalistic, with skillfully drawn lines to give the impression of a babirusa’s fur or, in Europe, the mane of a bucking horse. Taçon believes that the technical parallels “suggest that painting naturalistic animals is part of a shared hunter-gatherer practice rather than a tradition of any particular culture.” In other words, there may be something about such a lifestyle that provoked a common practice, rather than its arising from a single group.

“But Smith, of the University of Western Australia, argues that the similarities — ocher use, hand stenciling and lifelike animals — can’t be coincidental. He thinks these techniques must have arisen in Africa before the waves of migrations off the continent began. It’s a view in common with many experts. “My bet would be that this was in the rucksack of the first colonizers,” adds Wil Roebroeks, of Leiden University.

“The eminent French prehistorian Jean Clottes believes that techniques such as stenciling may well have developed separately in different groups, including those who eventually settled on Sulawesi. One of the world’s most respected authorities on cave art, Clottes led research on Chauvet Cave that helped to fuel the idea of a European “human revolution.” “Why shouldn’t they make hand stencils if they wanted to?” he asks, when I reach him at his home in Foix, France. “People reinvent things all the time.” But although he is eager to see Aubert’s results replicated by other researchers, he feels that what many suspected from the pierced shells and carved ocher chunks found in Africa is now all but inescapable: Far from being a late development, the sparks of artistic creativity can be traced back to our earliest ancestors on that continent. Wherever you find modern humans, he believes, you’ll find art.

See Separate Articles: EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

200,000-Year-Old Handprints from Tibet — the World’s Earliest Cave Art?

Fossilized children's handprints and footprints found near a hot spring in Tibet could be 200,000 years old, according to one study, making them the oldest cave art ever found. The prints were made in travertine stone which is soft when it's wet and hardens when it dries. There is a debate among archaeologists as to whether the handprints are really art and whether they are as old as claimed. A study on the prints was published September 2021 in the journal Science Bulletin. “The question is: What does this mean? How do we interpret these prints? They’re clearly not accidentally placed,” study co-author Thomas Urban, a scientist at Cornell University’s Tree-Ring Laboratory, said. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2024; Isis Davis-Marks, Smithsonian magazine, September 17, 2021

Isis Davis-Marks wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago, two children in what is now Quesang, Tibet, left a set of handprints and footprints on a travertine boulder. Seemingly placed intentionally, the now-fossilized impressions may be the world’s oldest known parietal, or cave, art. The prints were dated using the uranium series method. The ten impressions—five handprints and five footprints—are three to four times older than comparable cave paintings in Indonesia, France and Spain. Given their size and estimated age, the impressions were probably left by members by the genus Homo. The individuals may have been Neanderthals or Denisovans rather than Homo sapiens.

The discovery offers the earliest evidence of hominins’ presence on the Tibetan Plateau and supports previous research indicating that children were some of the first artists. Researchers discovered the hand and footprints — believed to belong to a 12-year-old and 7-year-old — near the Quesang Hot Spring in 2018. Though parietal art typically appears on cave walls, examples have also been found on the ground of caverns. “How footprints are made during normal activity such as walking, running, jumping is well understood, including things like slippage,” Urban told “These prints, however, are more carefully made and have a specific arrangement—think more along the lines [of] how a child presses their handprint into fresh cement.”

Do the Tibetan prints constitute art? Matthew Bennett, a geologist at Bournemouth University who specializes in ancient footprints and trackways, told Gizmodo that the impressions’ placement appears intentional: “It the composition, which is deliberate, the fact the traces were not made by normal locomotion, and the care taken so that one trace does not overlap the next, all of which shows deliberate care.” Other experts don’t necessarily buy into this. “I find it difficult to think that there is an ‘intentionality’ in this design,” Eduardo Mayoral, a paleontologist at the University of Huelva in Spain told NBC News.“And I don’t think there are scientific criteria to prove it—it is a question of faith, and of wanting to see things in one way or another.”

120,000-Year-Old Cattle Bone Carvings — the World’s Oldest Symbols

In 2021 archaeologists announced they had found a 120,00-year-old bone fragment — engraved with six lines — at the site of Nesher Ramla in Israel. The researchers determined that a right-handed craftsperson created the markings in a single session and suggested in may be a work of art of least a symbol of some sort., The discovery was made by scholars from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Haifa University and Le Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and published the journal Quaternary International in February 2021. “It is fair to say that we have discovered one of the oldest symbolic engravings ever found on Earth, and certainly the oldest in the Levant,” says study co-author Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology. “This discovery has very important implications for understanding of how symbolic expression developed in humans.”[Source: Rossella Tercatin, Jerusalem Post, Isis Davis-Marks, Smithsonianmag.com, February 8, 2021]

Rossella Tercatin wrote in the Jerusalem Post: “Because the markings were carved on the same side of a relatively undamaged bone, the researchers speculate that the engravings may have held some symbolic or spiritual meaning. Per the statement, the site where researchers uncovered the fragment was most likely a meeting place for Paleolithic hunters who convened there to slaughter animals. [Source: Rossella Tercatin,Isis Davis-Marks, Smithsonianmag.com, February 8, 2021]

Isis Davis-Marks wrote in Smithsonianmag.com, “The bone in question probably came from an auroch, a large ancestor of cows and oxen that went extinct about 500 years ago. Hunters may have used flint tools — some of which were found alongside the fragment — to fashion the engravings. Researchers used three-dimensional imaging and microscopic analysis to examine the bone and verify that its curved engravings were man-made, reports the Times of Israel. The analysis suggested that a right-handed artisan created the marks in a single session. “Based on our laboratory analysis and discovery of microscopic elements, we were able to surmise that people in prehistoric times used a sharp tool fashioned from flint rock to make the engravings,” says study co-author Iris Groman-Yaroslavski in the statement. [Source: Isis Davis-Marks, Smithsonianmag.com, February 8, 2021]

Scholars are unsure of the carvings’ meaning. Though it’s possible that prehistoric hunters inadvertently made them while butchering an auroch, this explanation is unlikely, as the markings on the bone are roughly parallel — a methodical feature not often observed in butchery marks, per Haaretz’s Ruth Schuster. The lines range in length from 1.5 to 1.7 inches long. “Making it took a lot of investment,” Zaidner tells Haaretz. “Etching [a bone] is a lot of work.”

“Archaeologists found the bone facing upward, which could also imply that it held some special significance. Since the carver made the lines at the same time with the same tool, they probably didn’t use the bone to count events or mark the passage of time. Instead, Zaidner says, the markings are probably a form of art or symbolism. “This engraving is very likely an example of symbolic activity and is the oldest known example of this form of messaging that was used in the Levant,” write the authors in the study. “We hypothesize that the choice of this particular bone was related to the status of that animal in that hunting community and is indicative of the spiritual connection that the hunters had with the animals they killed.”

“Scholars generally posit that stone or bone etchings have served as a form of symbolism since the Middle Paleolithic period (250,000 — 45,000 B.C.). But as the Times of Israel notes, physical evidence supporting this theory is rare. Still, the newly discovered lines aren’t the only contenders for the world’s earliest recorded symbols. In the 1890s, for instance Dutch scholar Eugene Dubois found a human-etched Indonesian clam shell buried between 430,000 and 540,000 years ago. Regardless of whether the carvings are the first of their kind, the study’s authors argue that the fragment has “major implications for our knowledge concerning the emergence and early stages of the development of hominin symbolic behavior.”

World's Oldest Known Drawing? — a 73,000-Year-Old Hashtag from South Africa

Blombos Cave

In 2018, scientists working in Blombos Cave in South Africa’s southern Cape region announced they had discovered the world’s oldest drawing — a 73 000-year-old cross-hatched sketch on a house-key-sized silcrete (stone) flake made with with an ochre crayon. It's unclear what the crisscrossed lines mean, but similar designs have been found at other early human sites in South Africa, Australia and France. The 3.8-centimeter (1.5-inch) -long rock flake was found near where shell beads and engraved stone tools were found and humans lived between 100,000 and 70,000 years ago. The study was published online on September 12, 2018 in the journal Nature. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, September 13, 2018]

Professor Christopher Henshilwood, who leads the team that made the discovery, told The Conversation: the drawing consists of a set of six straight sub-parallel lines crossed obliquely by three slightly curved lines. One line partially overlaps the edge of a flake scar. This suggests it was made after that flake became detached. The abrupt termination of all lines on the fragment edges indicates that the pattern originally extended over a larger surface. [Source: Christopher Henshilwood, Karen Loise van Niekerk, University of Bergen, The Conversation September 12, 2018]

The earliest known engraving, a zig-zag pattern incised on a fresh water shell from Trinil, Java, was found in layers dated to 540 000 years ago. In terms of drawings, a recent article proposed that painted representations in three caves of the Iberian Peninsula were 64,000 years old – this would mean they were produced by Neanderthals. So the drawing on the Blombos silcrete flake is the oldest drawing by Homo sapiens ever found.

The presence of similar cross-hatched patterns engraved on ochre fragments found in the same archaeological level and older levels suggests the pattern in question was reproduced with different techniques on different media. This is what we would expect to find in a society with a symbolic system embedded in different categories of artefacts. It’s also worth noting that patterns drawn on a stone are less durable than those engraved on an ochre fragment and may not survive transport. This may indicate that comparable signs were produced in different contexts, possibly for different purposes.

We would be hesitant to call it “art”. It is definitely an abstract design; it almost certainly had some meaning to the maker and probably formed a part of the common symbolic system understood by other people in this group. It’s also evidence of early humans’ ability to store information outside of the human brain.

Discovery and Analysis of the 73,000-Year-Old Drawing

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Study co-researcher Luca Pollarolo, a technical assistant in anthropology and African archaeology at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, made the actual discovery in 2015, when he was going through sediment samples in the lab, which excavators had painstakingly "removed millimeter by millimeter" from the cave, Henshilwood said. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, September 13, 2018]

As any skeptic would, the researchers wondered whether the drawing was made naturally or if it was created by H. sapiens. So, they reached out to study co-researcher Francesco d'Errico, a professor at the University of Bordeaux, who helped them photograph the artifact and determine that the lines had been applied to the rock by hand. The research team members even tried making their own designs with ochre on similar pieces of stone. The original artist (or artists) first smoothed the stone and then used an ochre crayon that had a tip between 0.03 to 0.1 inches (1 to 3 millimeters) thick, they found. (Ochre is a clay that can vary in hardness and can leave behind a mark similar to a crayon's.)

Moreover, the sudden termination of the red lines suggests that the pattern originally covered a larger surface. For this reason, the researchers suspect the flake was once part of a larger grindstone, Henshilwood said. The discovery of the ochre drawing is exceptional but not unexpected, said Emmanuelle Honoré, a fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge in England. That's because, in addition to other discoveries of early art, such as the carved shell, the study's authors published a study in 2001 about a bone fragment from Blombos Cave that has "comparable engraved lines in the same archaeological level," she said.

Modern Humans Who Made the 73,000-Year-Old Drawing

The drawing was made by Homo sapiens – people like us, who were our ancient direct ancestors. They were hunter-gatherers who lived in groups of between 20 and 40 people. The discovery adds to our existing understanding of Homo sapiens in Africa. They were behaviourally modern: they behaved essentially like us. They were able to produce and use symbolic material culture to mediate their behaviour, just like we do now. They also had syntactic language – essential for conveying symbolic meaning within and across groups of hunter gatherers who were present in southern Africa at that time.

The people who drew the hashtag were hunter-gatherers who excelled at catching big game, including hippos, elephants and 60-lb. (27 kilograms) fish, Henshilwood said. Given their proficient hunting skills, "they probably had a lot of free time to sit around the fire and talk and make things like jewelry," he said. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, September 13, 2018]

Blombos Cave is situated 50 meters from the Indian Ocean, elevated at 35 meters above sea level and 300 kilometers east of Cape Town. It’s very small – just 55 square meters. It was used as a temporary living site by hunter gatherer groups; they’d spend a week or two there at a time before moving on. The archaeological layer in which the Blombos drawing was discovered has also yielded other indicators of symbolic thinking. These include shell beads covered with ochre and, more importantly, pieces of ochres engraved with abstract patterns. Some of these engravings closely resemble the one drawn on the silcrete flake.

In older layers at Blombos Cave, dated at 100 000 years, they also discovered a complete toolkit consisting of two abalone shells filled with an ochre rich substance – a red paint – and all the artefacts associated with making it including seal bone used to add fat to the mixture. This discovery proves that our early ancestors could also make paint by 100 000 years ago. Engraved ochre slabs with various designs, including cross-hatched patterns, were also found in these older layer

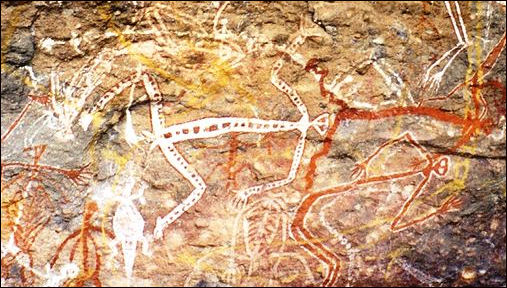

Early Modern Human Art in Australia

Another candidate of the world's oldest art are some mysterious cuplike designs and circular coin-like impression made on great orange boulders in a rock formations at the Jinmium site on the coast of Northern Territory in Australia. The impressions have been found on numerous boulders. In almost every case they have the same depth and the same 1.2-inch diameter width. One boulder has 3,500 markings. Scientists theorize the boulders may have marked important food sources or provided directions. Aboriginals in the area believe the markings represent ancestral being that turned to stone.

Richard Fullagar, an anthropologist at the Australian Museum in Sydney, dated the impressions and markings using the latest dating methods to be 75,000 years old, an astonishing date. The famous paleolithic cave paintings in France and Spain, by contrast, are 25,000 years old.

Using the thermolumiscence dating method, David Price of the School of Geosciences at the University of Woolonggong, has dated artifacts and ocher found in a rock shelter at Jinmium at 116,000 years old. Price dated a hand tool to be 176,000 years old — an even more astounding date that is hard to believe and would throw off many theories if it turns out to be true.

Hematite "crayons" dated with a new technique called optically simulated luminescence (which determines when sediments were last exposed to sunlight) are estimated to be between 53,000 and 60,000 years old. Researchers from the Australian National University in Canberra told National Geographic, "It's high-grade hematite. Ancient people ground it into red ocher powder. That means they had an interest in either coloring their bodies for ceremonies, painting clan designs on themselves, or putting art on walls or designs on their boomerangs."

The oldest rock paintings in Australia confirmed by carbon dating are 20,000 years old. An image of pregnancy drawn with ocher on a rock has been dated to be 35,000 years old using other dating methods. Some believe that other rock paintings may be 35,000 or 40,000 years old. A 30,000 year old piece of chiseled ocher was found at Lake Mungo.

An image of a pair birds found in Arnhem Land in northern Australia has been dated as being older than 40,000 years old because that is when the bird species in the image is thought to have gone extinct. Some have asserted it is Australia's oldest painting. The bird in question looks like an emu but is thought to be the megafauna bird genyornis, which has large, thick toes and shorter legs than an emu.

See Separate Article VERY, VERY OLD AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ROCK ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Australia's Anbangbang gallery Mimi Rock

Early Modern Human Ornaments

During the Aurignacian cultural period (about 40,000 to 28,000 years ago), modern humans wore rings, beads, pendants, anklets and necklaces made from bear, fox, or lion teeth interspersed with seas shells or ivory beads and other carefully-crafted personal adornments made of ivory, soapstone, bone, marine and freshwater shells, fossil coral, limestone, schist, talc-shistlignite, hematite, pyrite, teeth from other animals and the fossilized shells of extinct squids. [Source: Randal White, Natural History, May, 1993]

Early modern humans were very choosy about the materials chosen for ornaments. Only teeth of certain animals were selected. Of the thousand or so shell species available only a dozen were chosen. Facsimiles of shells and animal teeth were sometimes made with soapstone. Beads were sewn into clothing and carnivore teeth were used in belts and headbands.

Ivory was used almost exclusively to create adornments, not weapons or tools. Modern humans developed various techniques for working ivory, including drilling, gouging, carving and polishing it with metallic abrasives such as hematite. Some items have been found hundreds of miles from their sources, which seems to indicate that some form of trade existed.

The inhabitants of the Russian site of Sungir made elaborate personal ornaments of ivory and schist that often were in the form of abstract geometric designs. These include a wheel-like carved ivory disk, found in the 28,000-year-old grave of two children. See Burials

Beads found in France, dated to between 33,000 and 32,000 years ago, were made in several steps. First pencil-like rods were fashioned from ivory or soapstone and then inscribed and broken off in half-inch to three-quarter-inch sections. They were then perforated — by gouging the top of the section from both sides and meeting in the middle — and ground and polished into a bead with a hematite abrasive.

At a 36,000 year-old site in the Don Valley of Russia, archaeologists found beads from an amber-like mineral called belemnite that had been drilled from each side. Experiments have shown that each bead took about an hour to make. At a 20,000-year-old site called Sungir near Vladimir and Moscow, Russia an adult was buried with 3,000 beads and a child was found with 5,000 beads, representing between 3,000 and 5,000 hours of work. Scientists have speculated that beads buried with the child either were an expression of extreme grief or an indication of the child's high status.

World's Oldest Jewelry

In September 2021, researchers said in an article published by Science Advances they had discovered 33 shaped marine snail shells, dated as far back as 150,000 years. Ago, in a cave near Essaouira, about 400 kilometers southwest of Rabat, which they described as "the oldest ornaments ever discovered". According to the Robb Report: “The artifacts, which were discovered in the Bizmoune Cave near Morocco’s Atlantic coast between 2014 and 2018, have been through a series of rigorous tests to determine the age of shells and the surrounding sediment. Many of the beads are said to be between 142,000 and 150,000 years old. [Source: Rachel Cormack, Robb Report, November 25, 2021; AFP, September 24, 2021]

“Spanning roughly half an inch long, each bead was made from the shells of two different sea snail species. According to the excavation team, the holes in the center of each bead as well as the markings from wear and tear indicate that they were hung on strings or from clothing. Ancient beads from North Africa, such as these 33, are associated with the Aterian culture of the Middle Stone Age. These ancient settlers are widely considered to be the first to have worn what we now call jewelry.

In 2006, scientists said 100,000-year-old beads from sites in Algeria and Israel may represent the oldest known attempt at self-adornment known at that ttime . The beads, made from shells with holes bored into them, are 25,000 years older than similar beads discovered in 2004 ago in South Africa, the scientists reported in a June 2006 issue of the journal Science. "Our paper supports the scenario that modern humans in Africa developed behaviors that are considered modern quite early in time, so that in fact these people were probably not just biologically modern but also culturally and cognitively modern, at least to some degree," said study co-author Francesco d'Errico of the National Center for Scientific Research in Talence, France. [Source: Randolph E. Schmid, Associated Press, June 22, 2006 /*]

See Jewelry in EARLY MODERN HUMAN CLOTHES, JEWELRY AND MAKE UP europe.factsanddetails.com

60,000-Year-Old Etched Ostrich Eggs from South Africa

Smriti Rao of Discover wrote: “A cache of ostrich eggshell fragments discovered by archaeologists in South Africa could be instrumental in understanding how humans approached art and symbolism as early as the Stone Age. The eggshells, engraved with geometric designs, may indicate the existence of a symbolic communication system around 60,000 years ago among African hunter-gatherers [Source: Discovery News, Smriti Rao, Discover, March 3, 2010 /^]

“At a site known as the Diepkloof Rock Shelter, a team led by archaeologist Pierre-Jean Texier discovered fragments of 25 ostrich eggs that date back 55,000 to 65,000 years. In an online paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the archeologists revealed that the eggshell fragments were etched with several kinds of motifs, including parallel lines with cross-hatches and repetitive non-parallel lines. The scientists are confident that the markings are almost certainly a form of messaging — of graphic communication [ScienceNow, BBC]. /^\

“Further study of the fragments revealed that a hole had been drilled at the top of some eggshells, suggesting that the hunter-gatherers could have used them as water containers during long hunts in arid regions, as the Kalahari hunter-gatherers were known to do in more recent history. Scientists estimate that each egg could have held one liter of water. The patterns on the shells, they propose, could have been a symbolic way of acknowledging the individual who used the canteen, or which community or family the user belonged to. For scientists studying human origins, the capacity for symbolic thought is considered a giant leap in human evolution, and [what] sets our species apart from the rest of the animal world [BBC]. /^\

“Texier says the Diepkloof eggshells are special, because so many fragments were found with similar designs, and because engraving the tough ostrich shells would have been a hard task–showing that the designs were not merely scratched-in doodles. The hunter-gatherers also colored their shells by baking them.” /^\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Blombos Cave site, homo erectus art University of Amsterdam

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024