WHY WAS CAVE ART PRODUCED

Paintings dated between 42,000 and 12,000 B.C. were made by ancient modern humans in caves in France and Spain. The 36,000-year-old art in Pech Merle in France is one the older sites in Europe. Other old paintings, dating back 27,000 years, are found in Cosquer caves near Marseilles, entered via and underwater route, and Chauvet Cave, dated to 35,000 years ago. The youngest are around 10,000 years old. [Source: Judith Thurman, The New Yorker, June 23, 2008]

No one is sure why these caving paintings were made. Many of the them were — and still are — extremely difficult to get to and they were not lit with electricity as they are today. For these reason many archaeologist speculate they fulfilled some kind of ritualistic, ceremonial or religious function. They may have even been built to honor gods but it difficult to say for sure.

Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss famously argued in 1962 that primitive peoples chose to identify with and represent animals not because they were “good to eat” but because they were “good to think.” For ice age European cave painters, horses, rhinos, mammoths and lions were less important as dinner than as inspiration. Ancient Sulawesians, it seems, were likewise moved to depict larger, more daunting and impressive animals than the ones they frequently ate. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2016]

“The eminent French prehistorian JeanClottes has championed the theory that in Europe, where art was hidden deep inside dark chambers, the main function of cave paintings was to communicate with the spirit world. Benjamin Smith, a rock art scholar at the University of Western Australia. is likewise convinced that in Africa, spiritual beliefs drove the very first art. He cites Rhino Cave in Botswana, where archaeologists have found that 65,000 to 70,000 years ago people sacrificed carefully made spearheads by burning or smashing them in front of a large rock panel carved with hundreds of circular holes. “We can be sure that in instances like that, they believed in some sort of spiritual force,” says Smith. “And they believed that art, and ritual in relation to art, could affect those spiritual forces for their own benefit. They’re not just doing it to create pretty pictures. They’re doing it because they’re communicating with the spirits of the land.”

Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “Perhaps the explosion of creativity we see on the walls of these caverns was inspired in part by their sheer depth and darkness—or rather, the interplay of light and dark. Illuminated by the flickering light from fires or stone lamps burning animal grease, such as the lamps found in Lascaux, the bumps and crevices in the rock walls might suggest natural shapes, the way passing clouds can to an imaginative child. In Altamira, in northern Spain, the painters responsible for the famous bison incorporated the humps and bulges of the rock to give their images more life and dimension. Chauvet features a panel of four horse heads drawn over subtle curves and folds in a wall of receding rock, accentuating the animals’ snouts and foreheads. Their appearance changes according to your perspective: One view presents perfect profiles, but from another angle the horses’ noses and necks seem to strain, as if they are running away from you. In a different chamber a rendering of cave lions seems to emerge from a cut in the wall, accentuating the hunch in one animal’s back and shoulders as it stalks its unseen prey. As our guide put it, it is almost as if some animals were already in the rock, waiting to be revealed by the artist’s charcoal and paint.[Source: Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ;Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org;Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net; Websites on Neanderthals: Neandertals on Trial, from PBS pbs.org/wgbh/nova; The Neanderthal Museum neanderthal.de/en/ ; Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RELATED ARTICLES:

WORLD'S EARLIEST ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CAVE ART europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HOW EARLY HUMANS MADE ART: METHODS, MATERIALS AND INTOXICATION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

IMAGES IN EARLY MODERN HUMAN ART: ANIMALS, HAND PRINTS, FIGURES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL ART, ENGRAVINGS AND JEWELRY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL PAINTINGS: 66,500 YEARS OLD AND CONTROVERSY OVER THEM europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

CAVE ART IN SPAIN europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CAVE ART IN FRANCE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LASCAUX CAVE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

CHAUVET CAVE: PAINTINGS, IMAGES, SPIRITUALITY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST SCULPTURES factsanddetails.com ;

VENUS STATUES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“What Is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity” by Jean Clottes Amazon.com;

“The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist Amazon.com;

“The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art” by Paul Bahn (2017) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008) Amazon.com;

“Cave Art (World of Art)” (2017) by Bruno David Amazon.com;

“Cave Art: A Guide to the Decorated Ice Age Caves of Europe” by Paul Bahn Amazon.com;

“Images of the Ice Age” by Paul G. Bahn Amazon.com;

“The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art” by David Lewis-Williams (2004) Amazon.com;

“Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne” by Christine Desdemaines-Hugon (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs” by Mario Ruspoli (1987) Amazon.com;

“Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave” by Jean-Marie Chauvet, Eliette Brunel Deschamps (1996) Amazon.com;

“Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times” by Jean Clottes (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Cave of Altamira” by Matilde Muzquiz Perez-Seoane, Frederico Bernaldo de Quiros (1999) Amazon.com;

What Caused Early Humans to Produce Art

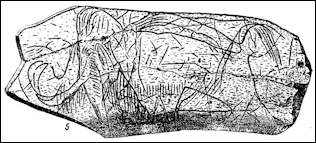

Mammoth carved on ivory from Florida Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “It seems unlikely...that some genetic “switch” flipped in our African ancestors to produce the capacity for a new, higher-order level of cognition that, once it evolved, produced a lasting change in human behavior. So how do we explain these apparently sporadic flare-ups of creativity? One hypothesis is that the cause was not a new kind of person but a greater density of people, with spikes in population sparking contact between groups, which accelerated the spread of innovative ideas from one mind to another, creating a kind of collective brain. Symbols would have helped cement this collective brain together. When populations again fell below critical mass, groups became isolated, leaving new ideas nowhere to go. What innovations had been established withered and died. [Source: Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

“Such theories are difficult to prove—the past holds its secrets close. But genetic analyses of modern populations do point to a surge in population in Africa 100,000 years ago. A 2009 study conducted by Adam Powell, Stephen Shennan, and Mark G. Thomas of University College London also provides some statistical support for the power of larger populations to generate innovation. And research by Joseph Henrich, now at the University of British Columbia, suggests that as populations shrink, they have an increasingly difficult time holding on to the innovations they invented in the first place. The inhabitants of the island of Tasmania had been making bone tools, cold-weather clothing, and fishing equipment for 15,000 years before these advances disappear from the archaeological record some 3,000 years ago. Henrich argues that when sea levels rose 12,000 to 10,000 years ago and isolated Tasmania from the rest of the world, the indigenous population of perhaps 4,000 individuals was simply not large enough to keep the cultural traditions alive.

“Why Africa’s archaeological record grows dim for 150 centuries is by no means clear. Perhaps pestilence, natural catastrophe, or a sharp swing in climate caused populations to collapse. Yet Francesco d’Errico, an archaeologist at the University of Bordeaux, points out that although harsh conditions might spell doom for some cultures, others might be spurred on by them. There is no set formula. “Each region of the globe produced cultures with a number of different trajectories,” says d’Errico. “You could have situations where some short-term chaotic disaster might wipe out a culture in one area, but in another, people were able to take advantage of the challenge.” He likens it to a recipe. “Even if the ingredients are the same, you don’t necessarily get the same outcome.”“

Art and Abstraction Set Humans Apart from Animals?

Melissa Hogenboom wrote for the BBC: “One study proposes that our technological innovation was key for our migration out of Africa. We started to assign symbolic values to objects such as geometrical designs on plaques and cave art. There is little evidence that any other hominins made any kind of art. One example, which was possibly made by Neanderthals, was hailed as proof they had similar levels of abstract thought. However, it is a simple etching and some question whether Neanderthals made it at all. The symbols made by H. sapiens are clearly more advanced. We had also been around for 100,000 years before symbolic objects appeared so what happened? [Source: Melissa Hogenboom, BBC, July 6, 2015 |::|]

“Somehow, our language-learning abilities were gradually "switched on", Tattersall argues. In the same way that early birds developed feathers before they could fly, we had the mental tools for complex language before we developed it. We started with language-like symbols as a way to represent the world around us, he says. For example, before you say a word, your brain first has to have a symbolic representation of what it means. These mental symbols eventually led to language in all its complexity and the ability to process information is the main reason we are the only hominin still alive, Tattersall argues. It's not clear exactly when speech evolved, or how. But it seems likely that it was partly driven by another uniquely human trait: our superior social skills. |::|

“We are unique in the level of abstractness with which we can reason about others' mental states This tells us something profound about ourselves. While we are not the only creatures who understand that others have intentions and goals, "we are certainly unique in the level of abstractness with which we can reason about others' mental states", says Katja Karg, also of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. |::|

“When you pull together our unparalleled language skills, our ability to infer others' mental states and our instinct for cooperation, you have something unprecedented. Us.Just look around you, Tomasello says, "we're chatting and doing an interview, they (chimps) are not." We have our advanced language skills to thank for that. We may see evidence of basic linguistic abilities in chimpanzees, but we are the only ones writing things down. |::|

“We tell stories, we dream, we imagine things about ourselves and others and we spend a great deal of time thinking about the future and analysing the past.There's more to it, Thomas Suddendorf, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Queensland in Australia is keen to point out. We have a fundamental urge to link our minds together. "This allows us to take advantage of others' experiences, reflections and imaginings to prudently guide our own behaviour. "We link our scenario-building minds into larger networks of knowledge." This in turn helps us to accumulate information through many generations.” |::|

Art Not Accompanied by Genetic Mutations

Hannah Devlin wrote in The Guardian: “A study found that the advent of modern human behaviours around 100,000 years ago, indicated by cave art and more sophisticated tools, does not appear to have been accompanied by any notable genetic mutations. “Your genome contains the history of every ancestor you ever had,” said Swapan Mallick, a geneticist at Havard Medical School who led the analysis of the genomes of people from 142 distinct populations. [Source: Hannah Devlin, The Guardian, September 21, 2016 |=|]

“The study also suggests that the KhoeSan (bushmen) and Mbuti (central African pygmies) populations appear to have split off from other early humans sooner than this, again suggesting that there was no intrinsic biological change that suddenly triggered human culture. “There is no evidence for a magic mutation that made us human,” said Willerslev. |=|

“Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said the findings would be controversial in the field, adding: “It either means that the behaviours were developed earlier, they developed these behaviours independently, they acquired them through exchanges of ideas with other groups, or the estimated split times are too old.” Ya pulingina. Bringing these words to life is an extension of our identity.” |=|

Why Early Man May Have Painted

"We do not precisely why [early modern humans] made these earliest surviving fixed images," wrote historian Daniel Boorstin in The Creators , "We brashly assume that he must have had a reason. But where he made them tells us something." Many theorize that because the images were typically of animals early man hunted the images were connected in some way with bringing success to the hunt and ensuring there was enough to eat.

"He must have felt a community with the animals he hunted, with whom his own life was bound," Boorstin wrote. “Here, in the every act of trying to “represent” — to represent — his quarry, the fearful powers all around him, he was awakened to another power in him, his power to create. Here in the secret passages of deep limestone caves, in the womb of the earth, he felt safe while he created. Was any of man's other discoveries more shocking or mysterious?"

Some speculate that the act of painting may have been more important than the paintings themselves. One scholar told the Washington Post, "some were not meant to be seen. You'd have to have climb up into narrow passages on your hands and knees to see them, which leads us to believe it was made for contact with the spirits."

There are no images of violence or warfare although three sites there are four drawings of a man's limbs and torso pierced with spearlike lines. One of the interesting things about the caves with the exception of Vilhonneur (where skull of a young man was found) and Cussac (where five adults were found) the caves are absent of human remains.

The mysterious circles, dots and chevrons on some animals, some scientists believe, were created by a painter in an altered state. Rock paintings by !Kung Bushmen are often made by shaman in a trancelike state to ward off demons.

Was Cave Art Like Animation?

Chip Walter wrote in National Geographic: “In his book La Préhistoire du Cinéma, filmmaker and archaeologist Marc Azéma argues that some of these ancient artists were the world’s first animators, and that the artists’ superimposed images combined with flickering firelight in the pitch-black caves to create the illusion that the paintings were moving. “They wanted to make these images lifelike,” says Azéma. He has re-created digital versions of some cave images that illustrate the effect. The Lion Panel in Chauvet’s deepest chamber is a good example. It features the heads of ten lions, all seemingly intent on their prey. But in the light of a strategically positioned torch or stone lamp, these ten lions might be successive characterizations of just one lion, or perhaps two or three, moving through a story, much like the frames of a flip-book or animated film. Beyond the lions stands a cluster of rhinoceroses. The head and horn of the top one are repeated staccato-like six times, one image above the other, as if thrusting upward, its whole body shuddering with multiple outlines. [Source: Chip Walter, National Geographic, January 2015]

“Azéma’s interpretation fits with that of eminent prehistorian Jean Clottes—the first scientist to enter Chauvet, only days after its discovery. Clottes believes the images in the cave were intended to be experienced much the way we view movies, theater, or even religious ceremonies today—a departure from the real world that transfixed its audience and bound it in a powerful shared experience. “It was a show!” says Clottes.

“Thousands of years later you can still feel the power of that show as you walk the chambers of the cave, the sound of your own breath heavy in your ear, the constant drip, drip of the water falling from the walls and ceilings. In its rhythm you can almost make out the thrum of ancient music, the beat of the dance, as a storyteller casts the light of a torch upon a floating image, and enthralls the audience with a tale.”

Early Interpretations of Early Man Cave Paintings

Some scholars speculate that early cave painting were made by people who performed ritual hunts to kill the spirits of the animals to make them less formidable during the hunt and to prevent them from coming back to haunt the hunters. They also speculate that the concept of spirit developed out of the conception that something alive contained a spirit and something dead didn't, and when an animal died its spirit had to go somewhere. [Source: History of Art by H.W. Janson, (Prentice Hall)]

Many of the cave paintings are believed to have been involved in rituals and ceremonies because many of the caves are so hard to get to, sometimes involving climbs up steep slopes, squeezes through narrow fissures and stomach crawling through tiny tunnels. Anthropologists have long noted that the more risky and uncertain an activity is the more likely it is to be surrounded by magical practices. Because hunting is a risky, uncertain activity, many scientists believe that the painting may have been part of a magical ritual.

Abbe Henri Brueil, a French priest who skipped Mass to copy hundreds of paintings, is sometimes called the “Pope of Prehistory." He helped classify cave art before World War II, hypothesizing the art was involved with rituals of “hunting magic” and were an attempt to capture the beauty of the animals the hunters hunted — a view that was discredited in later studies. The post-war, Marxist German art historian Max Raphael, concluded the animals represented clan totems and the paintings depicted strife and alliances associated with clan warfare.

In 1962, French archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire wrote a doctoral thesis entitled The Meaning of Paleolithic Art . The work made her famous and it is still widely embraced today. In it she chided her predecessors for taking too many liberties in their interpretations and warned about looking at modern hunter-gatherers for insights. Instead she opted for more of a number-crunching, spacial and geometric approach in which images were carefully catalogued, with notes taken on the gender, action and position of figures, and notes were made on they way they were grouped and their frequency and spacial relation to things like hand prints and abstract symbols.

In his book Lascaux , Norbert Aujoulat noted that often when horses, aurochs and stags are drawn together the horses are on the bottom, the aurochs are in middle and the stag are on top and the variations of their coats corresponds to respective mating seasons. This in turn has links to the fertility cycle and is perhaps sacred or symbolic.

Later Interpretations of Early Man Cave Paintings

In his 1996 book The Shamans of Prehistory , co-authored by South African archaeologist David Lewis-Williams, Clottes, defied the taboo of bringing in outside sources, and related the work of the cave artists to shamanism among hunter-gatherers, particularly the San (Bushmen) of southern Africa and to experiments on visual illusion caused by drugs, music, fashion and oxygen deprivation that produce images in three stages: 1) patterns, points, zigzags and other abstract forms; 2) the morphing of these forms into objects, such as the zigzags become snakes; and 3) the deepest stage in which subjects are called up in a world of hallucinations, monsters and animals. Clottes believes the cave painting represent the experiences and vison of shaman, with animals often incorporating the contours of the caves because they were regarded as part of the cave. The book generated a lot of controversy and criticism, with one critics calling it “psychedelic ravings."

In defense of his book Clottes told The New Yorker, “Everyone agrees that the paintings are in some way, religious. I'm not a believer myself, and I'm certainly not a mystic. But Homo sapiens is Homo spiritualis . The ability to make tools defines less than the need to create belief systems that influence nature. And shamanism is the most prevalent belief system of hunter-gatherers."

Describing an experiment he did that involved bringing some elders from a group of Australian Aboriginal hunter-gatherers to Lascaux Cave, Jean-Michel Geneste told The New Yorker, “When they entered the cave, they took a while to get their bearing. Yes, they said, it was an initiation site. The geometric signs, in red and back, reminded them of their clan insignias, the animals and engravings of figures from their creation myths." But Geneste also believes the caves could be like a modern church, with different meanings to different people, offering spiritual, social and meditative opportunities.

Dale Guthrie, a professor of zoology at the University of Alaska, has gone out and hunted animals similar to ones in the painting to gain insights into what the cave painters were all about. In his book The Nature of Paleolithic Art , he emphasized the creative “freedom," playfulness and the sexuality of the art, showing little patience for those who get too hung up on small details and metaphysical explanations. Based on an examination of hand prints he has theorized that a lot of the art was created by teenage boy who drew pubic triangles and other things to amuse themselves, Critics of his interpretation say his ideas may explain some of the art but is a misrepresentation of the most significant art.

Reading Australian Rock Art

Djulirri, a rock shelter in the Wellington Range of Arnhem Land on Australia's north coast, contains1,100 separate paintings, including the overlapping spirit figure and kangaroo above them. Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, the aboriginal elder “Ronald Lamilami first came to Djulirri (JUH-lih-ree) in the early 1960s, when he was three years old. On foot and by canoe, his father, Lazarus, showed him the route that their Aboriginal ancestors had used for thousands of years, following food and shelter inland from Australia's north coast. Each wet season, those ancestors spent several months at Djulirri, a well-concealed rock shelter in a horseshoe-shaped valley. “I remember paintings on rocks," Lamilami says. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2011]

Lamilami, the aboriginal owner of the sit has worked with archaeologist and rock art specialist Paul S. C. Taçon of Griffith University in Gold Coast, Australia to interpret the rock art. Djulirri's additions and overpaintings cover an immense period of time. Tacon traces its early images back 15,000 years and the last major additions to the panels were painted about 50 years ago.

“Djulirri is among the top handful of rock art sites in the world, and in its layers of pigments and stained rock is an abundance of information about Aboriginal culture and how it dealt with the sweeping changes of the last few centuries." “All the stories are here in the rock” says Lamilami. “Each year, a new concept would be drawn - what happened the year before that, it's a time lapse." Patel points out that “Other rock art sites, such as Lascaux in France, capture only a narrow period of time, and even the deepest archaeological deposits aren't willful creations like this. Djulirri might be the longest continuously updated human record in the world." In other words according to Lamilami, this site represents an annually updated record of what happened to his people over that span of time, much like the winter counts of many of the Native American tribes of the Great Plains of North America.

Prehistoric Art, 20,000–8000 B.C.

Laura A. Tedesco wrote in for the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Art, as the product of human creativity and imagination, includes poetry, music, dance, and the material arts such as painting, sculpture, drawing, pottery, and bodily adornment. The objects and archaeological sites presented in the Museum's Timeline of Art History for the time period 20,000–8000 B.C. illustrate diverse examples of prehistoric art from across the globe. All were created in the period before the invention of formal writing, and when human populations were migrating and expanding across the world. By 20,000 B.C., humans had settled on every continent except Antarctica. The earliest human occupation occurs in Africa, and it is there that we assume art to have originated. African rock art from Apollo 11 and Wonderwerk Caves contain examples of geometric and animal representations engraved and painted on stone. In Europe, the record of Paleolithic art is beautifully illustrated with the magnificent painted caves of Lascaux and Chauvet, both in France. Scores of painted caves exist in western Europe, mostly in France and Spain, and hundreds of sculptures and engravings depicting humans, animals, and fantastic creatures have been found across Europe and Asia alike. Rock art in Australia represents the longest continuously practiced artistic tradition in the world. The site of Ubirr in northern Australia contains exceptional examples of Aboriginal rock art repainted for millennia beginning perhaps as early as 40,000 B.C. The earliest known rock art in Australia predates European painted caves by as much as 10,000 years. [Source: Laura A. Tedesco, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Independent Scholar, metmuseum.org, August 2007 \^/]

“In Egypt, millennia before the advent of powerful dynasties and wealth-laden tombs, early settlements are known from modest scatters of stone tools and animal bones at such sites as Wadi Kubbaniya. In western Asia after 8,000 B.C., the earliest known writing, monumental art, cities, and complex social systems emerged. Prior to these far-reaching developments of civilization, this area was inhabited by early hunters and farmers. Eynan/Ain Mallaha, a settlement in the Levant along the Mediterranean, was occupied around 10,000–8000 B.C. by a culture named Natufian. This group of settled hunters and gatherers created a rich artistic record of sculpture made from stone and bodily adornment made from shell and bone. \^/

“The earliest art of the continent of South Asia is less well documented than that of Europe and western Asia, and some of the extant examples come from painted and engraved cave sites such as Pachmari Hills in India. The caves depict the region's fauna and hunting practices of the Mesolithic period. In Central and East Asia, a territory almost twice the size of North America, there are outstanding examples of early artistic achievements, such as the expertly and delicately carved female figurine sculpture from Mal'ta. The superbly preserved bone flutes from the site of Jiahu in China, while dated to slightly later than 8000 B.C., are still playable. The tradition of music making may be among the earliest forms of human artistic endeavor. Because many musical instruments were crafted from easily degradable materials like leather, wood, and sinew, they are often lost to archaeologists, but flutes made of bone dating to the Paleolithic period in Europe (ca. 35,000–10,000 B.C.) are richly documented. \^/

Woolly mammoth cave art

“North and South America are the most recent continents to be explored and occupied by humans, who likely arrived from Asia. Blackwater Draw in North America and Fell's Cave in Patagonia, the southernmost area of South America, are two contemporaneous sites where elegant stone tools that helped sustain the hunters who occupied these regions have been found.” \^/

“Whether the prehistoric artworks illustrated here constitute demonstrations of a unified artistic idiom shared by humankind or, alternatively, are unique to the environments, cultures, and individuals who created them, is a question open for consideration. Nonetheless, each work or site superbly characterizes some of the earliest examples of humans' creative and artistic capacity.” \^/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024