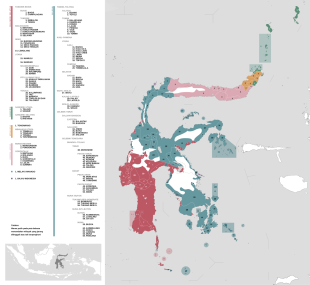

ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN SULAWESI

Tomini live in northern Sulawesi. Also known as the Tiadje, Tialo, Toi-toli, Tominers, they live primarily on the coast in stilted houses and are subsistence farmers who produce maize, wet rice and sago and are very much involved in the production of cloves. Most are Sunni Muslims, with some animist tribes living in small enclaves in the mountains. These tribes have been the object of acculturation and relocation efforts by the Indonesian government. They numbered around 74,000 in 1980. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Tomini population in the 2020s was around 32,000, of which around 90 percent were Muslims. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Wikipedia]

Sangir People are the indigenous people of the Sangihe (Sangir) and Talaud island chains, situated between southern Mindanao and northern Sulawesi. Also known as Sangirese, Sangirezen or Talaoerezen, they speak Sangir—also called Sangil, Sangihé, or Sangirese—an Austronesian language and have traditionally been concentrated in the province of North Sulawesi in Indonesia and the Region of Dávao in the Philippines.

The Sangir population is around 600,000 people, with 450,000 in North Sulawesi, 7,500 Gorontalo, as well as 11,000 in South-Central Mindanao and 8,850 in the Davao Region of the Philippines. In Indonesia, the Sangir have long been exposed to both Muslim and Christian influences, though today the majority are Christian. The Sangir are sometimes confused with the Sangil, a smaller group of roughly 4,000 people living on islands off the southern coast of Mindanao. The Sangil are Philippine Muslims descended from Sangir migrants who moved to Mindanao in the seventeenth century or earlier. They are now regarded as a distinct group and are considered Filipino rather than Indonesian.

Minahasans live in a mountainous area in the extreme northeastern section of the northern peninsula on Sulawesi. Also known as the Minahasa, Minahasser, Minhasa, Tombalu, Tombulu, Toumbulu, they are a confederation of groups that joined together to fight their neighbors, the Bolaang Mongondow. The Minahasans raise wet and dry rice and others crops and are known as being good in business and have a tradition of service on international shipping lines. They are regarded as being outward looking and possessing excellent language and navigation skills. In the past they had close contact with the Dutch. They are mostly Christians and their traditional culture has largely disappeared. The Minahasans are said to have descended from the marriage of a mother and son who were created by gods that rose from the sea. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINAHASANS: HISTORY, LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL SULAWESI: BADA VALLEY MEGALITHS, LAKE POSO, LORE LINDU NATIONAL PARK factsanddetails.com

NORTH SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

DIVING IN NORTH SULAWEST BUNAKEN ISLAND AND THE LEMBEH STRAIT factsanddetails.com

GORONTALO factsanddetails.com

SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

Gorontalo People

The Gorontalo People are the dominant group in northwestern Sulawesi. Also known as the Gorontalese, Gorontalo, Holontalo, Hulontal, they are mostly Sunni Muslims who have kept many of their traditional beliefs alive. For example, at the end of Ramadan, they engage in Tombbilotohe; a cultural celebration with oil lamps, which are lit around around mosques and settlements. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

According to the 2010 census their Total population at that time was 1,251,494, with 925,626 in Gorontalo province, 187,163 in North Sulawesi and 105,151 in Central Sulawesi. The six subgroups are the Gorontalo, Suwawa, Limbotto, Bolango, Atinggola, and Boelemo.The languages spoken by the latter four groups have disappeared, leaving only Gorontalo and Suwawa, which are also being replaced by Bahasa Indonesia. Wall Street Journal Wikipedia]

The Gorontalo region is estimated to have been established as a cultural area about 400 years ago. It became one of the key centers for the spread of Islam in eastern Indonesia, alongside Ternate and the Bone state. By 1525, when the Portuguese reached North Sulawesi, Islam was already firmly established under the rule of King Amay, and the Gorontalo lands were divided among several Muslim polities, including Gorontalo, Limboto, Suwawa, Boalemo, and Atinggola. Over time, Gorontalo developed into an important hub of education and trade in North Sulawesi. The capital of the Gorontalo Kingdom originally emerged at Hulawa village, located along the Bolango River. Even before European contact, Gorontalo society was organized around a kinship-based system known as pohala’a, a form of family bonding that continues to shape social life today.

Gorontalo Customs and Views on Life

Among the Gorontalo people, custom (adat) is regarded as a source of honor, social norms, and even a guide for governance. This outlook is encapsulated in the expressions “Adat bersendi sara” and “Sara bersendi Kitabullah,” which mean that custom is founded upon religious law (sara), and that religious law, in turn, is based on the Qur’an. As a result, Gorontalo social life is deeply infused with Islamic values and ideals of moral conduct. [Source: Wikipedia]

Gorontalo philosophy of life is expressed in traditional maxims. One is batanga pomaya, nyawa podungalo, harata potombulu, which conveys the idea that the body is devoted to defending the homeland, life is pledged in loyalty, and wealth must be handled carefully because it can create social problems. Another saying, lo iya lo ta uwa, ta uwa lo lo iya, boodila polucia hi lawo, emphasizes that a leader possesses authority but must not exercise it arbitrarily. Together, these philosophies stress responsibility, restraint, and ethical leadership.

Gorontalo wedding rituals, known as Momonto and Modutu, follow strict procedures observed by both families. The ceremonies are held alternately at the homes of the bride and groom and may last for more than two days. Relatives and neighbors cooperate in preparing the event, reflecting strong communal values. During the ceremonies, the bride and groom wear traditional attire called Bili’u, and the bridal bedroom plays a ceremonial role during the reception, in accordance with custom.

Another significant tradition is Molontalo or Tontalo, the “seventh-month” pregnancy ceremony. This ritual expresses gratitude for a pregnancy that has reached seven months. Both parents wear traditional Gorontalo clothing, and a symbolic procession takes place in which the expectant father carries a young girl around the house before entering to meet his pregnant wife. A coconut-leaf cord that had been tied around the mother is then cut, symbolizing release and protection. Seven dishes are prepared on seven trays and shared with guests, reinforcing themes of blessing, fertility, and communal harmony.

Gorontalo Life and Culture

Traditionally, the Gorontalese have been swidden farmers, cultivating wet and dry rice along with maize, yams, and millet, while coconuts are grown as an important commercial crop. Coastal communities supplement agriculture with fishing. Traditional Gorontalo attire is brightly multicolored, with each color carrying symbolic meaning, and the people are also well known for their rich and highly developed musical traditions. [Source: Wikipedia]

Gorontalo society is organized around a kinship system known as pohala’a, inherited from the region’s former kingdoms. There are five pohala’a: Gorontalo, Limboto, Suwawa, Boalemo, and Atinggola, with Gorontalo being the most prominent. Strong kinship ties foster a high degree of social cohesion, and internal conflict is rare. Mutual cooperation (huyula) remains a central value in daily life, and disputes are typically resolved through discussion and consensus.

Villages form the basic settlement pattern. The traditional Gorontalo house, called Dulohupa, is a stilted wooden structure with a thatched roof and several interior rooms, accessed by twin staircases at the entrance. In the past, Dulohupa served as a venue for deliberations by royal rulers, and examples still survive in several Gorontalo subdistricts. Another traditional house type, the Bandayo Poboide, is now nearly extinct; one of the few remaining examples stands in front of the Gorontalo Regent’s office in Limboto.

Gorontalo cultural expression includes the Polopalo dance, a popular traditional performance known throughout Gorontalo and even into North Sulawesi. Another important cultural form is Lumadu, an oral tradition of riddles, metaphors, and parables. Children use Lumadu as word games, while adults employ its metaphorical form in conversation to show politeness, enrich dialogue, and convey moral or social values.

Mongondow

Mongondow live in northern Sulawesi on the Minahassa peninsula. Also known as the Bolaang-Mongondese, Bolaang-Mongondo, Mongondou and Bolaang Mongondow, they live in coastal areas and on highland plateaus, where they grow wet rice, sago, yams and cassava and raise of pigs, cattle, buffalo, goats, and chickens.. Their society has traditionally had three divisions: nobles, commoners and slaves. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

According to a 1983 estimate the population of the Bolaang Mongondow was over 1.5 million and about 90 percent are Muslims. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 312,00 Mongondow in the early 2020s and 55 percent were Christian. The Mongondow people consist of several sub-ethnic groups residing in North Sulawesi and Gorontalo, including: 1) Bolaang Mongondow; 2) Bolaang Uki; 3) Kaidipang Besar; 4) Bintauna; 5) Buhang; 5) Korompot; 7) Mokodompis. The Mongondow people commonly speak Mongondow, Bolango, and Bintauna languages in daily life. Linguistically, these languages belong to the Greater Central Philippine branch, alongside Gorontalo. Manado Malay is widely used for interethnic communication throughout North Sulawesi.

The Mongondow people are an Austronesian ethnic group. They have traditionally been concentrated in North Sulawesi and Gorontalo provinces. Mongondow villages were typically arranged along roads, particularly on upland plateaus. Islam was introduced around 1830. Most non-Muslims are Protestant Christianity. Descent is bilateral along both male and female lines.

History of the Mongondow

Historically, the Mongondow were united under a single political entity, the Kingdom of Bolaang Mongondow, which after Indonesian independence became the basis for the western regencies of North Sulawesi. According to Mongondow oral tradition, their ancestors descended from Gumalangit and Tendeduata, as well as from Tumotoiboko and Tumotoibokat, who lived on Mount Komasan in present-day Bintauna, North Bolaang Mongondow Regency. Their descendants eventually became the Mongondow people. As the population grew, Mongondow communities spread to areas such as Lombagin, Buntalo, Pondoli’, Ginolantungan, Passi, Lolayan, Sia’, Bumbungon, Mahag, and Siniow. During this early period, subsistence was based on hunting, fishing, sago processing, and gathering forest tubers, as agriculture had not yet developed. [Source: Wikipedia]

By the thirteenth century, local leaders known as Bogani—heads of Mongondow territorial groups—had united to establish a centralized authority known as Bolaang. The name reflected its maritime orientation. Through a council meeting (bakid), the Bogani appointed Mokodoludut, a Bogani from Molantud, as the first king (Punu’) of the Bolaang Kingdom.

In the sixteenth century, following the departure of King Mokodompit to Siau Island, the kingdom entered a period of political instability. Prince Dodi Mokoagow, the strongest candidate to succeed the throne, was killed in the interior of Manado. Governance was temporarily assumed by a Bogani from Mulantud named Dou’. When Mokodompit’s son reached adulthood in Siau, he returned and was installed as the seventh king of Bolaang Mongondow. Known by the princely title Abo (Tadohe or Sadohe), and born to a princess from the Kingdom of Siau, his reign marked the restoration of the kingdom’s governing system.

During the reign of King Salmon Manoppo (1735–1764), the Bolaang Mongondow Kingdom engaged in intense conflict with the Dutch. King Salmon was captured and exiled to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, provoking widespread unrest among the Mongondow population. Eventually, the Dutch returned the king, and from that period onward the kingdom became known as Bolaang Mongondow, combining the territorial name with the ethnic identity.

In 1901, the kingdom’s territory was formally incorporated into the Dutch colonial administrative system as the Bolaang Mongondow Subdivision (Onderafdeling), which included the administrative regions of Bintauna, Bolaang Uki, and Kaudipang Besar under the Manado Division. The Bolaang Mongondow Kingdom officially came to an end on July 1, 1950, when King Tuang Henny Yusuf Cornelius Manoppo abdicated and declared allegiance to the Republic of Indonesia. In contemporary usage, Mongondow generally refers to mountainous areas, while Bolaang denotes coastal regions. During the regency of Oemarudin Nini Mokoagow (1966–1976), a new village named Mongondow was established in Kotamobagu following the redelineation of Motoboi Village.

Ethnic Groups in Central Sulawesi

Balantak live on the most easterly end of east-central Sulawesi. Also known as the Kosian and Balantak, thye have traditionally been slash-and -burn agriculturists and raised domestic animals such as goats and dogs. Their ectangular raised houses are scattered among slash-and-burn fields, with small clusters around the local chief. Domestic animals include dogs, fowl, and goats. Descent is bilateral. Formerly, the Balantak were ruled by local chiefs and integrated into the Ternate Sultanate. Their traditional belief system revolves around ancestor worship. Many are now Muslims and Christians. They numbered about 30,000 in the early 1980s and are closely related to the Banggai. According to Joshua Project their population was around 36,000 in the 2020s and 10 to 50 percent were Christians. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Banggai inhabit the Banggain Archipelago off the tip of the peninsula in east-central Sulawesi. Also known as the Aki, Mian Banggai, Mian Sea-Sea, they too have traditionally been slash-and -burn agriculturist but they also have raised coconuts as a cash crop. In the past there was a Kingdom of Banggai. Today the Banggai are divided into two subgroups, the Seasea people who live in mountainous area and the Banggai people who live in the coastal area. The Banggai have similarities in language, culture and tradition to Saluan people and Balantak people which inhabit Banggai Regency. According to Joshua Project their population was around 186,000 in the 2020s and 45 percent were Muslims and 10 to 50 percent were Christians. They numbered around 86,000 in 1978 and incorporate animism into their Muslim and Christian beliefs. ~

Saluans live in east-central Sulawesi. Also known as the Loinan, Loinanezen, Loindang, Madi and To Loinang, they are mostly subsistence farmers who live in raised wood or bamboo houses in villages with no more than 7000 inhabitants. Their traditional religion is based on ancestor worship and their name comes from King Saluan, the youngest of three children of a former local ruler. The Saluan are divided into several subgroups distinguished mainly by dialect and region of origin: 1) Saluan Lingketeng (from the interior of Pagimana District); 2) Saluan Loinang (from the interior of Simpang Raya District); and 3) Saluan Obo (from the inland border region between Banggai Regency and Tojo Una-Una Regency) According to Joshua Project the coastal Saluan population was around 146,000 in the 2020s and 65 percent were Muslims and 10 to 50 percent were Christians.

Saluan culture includes distinctive rituals: 1) the umapos welcoming ceremony, in which two men ritually receive guests, offering respect and protection with yellow rice thrown toward them and their boats, accompanied by songs praising God; 2) monggisin, a tooth-filing ritual required of young men and women before adulthood or marriage, particularly practiced among the Loinang subgroup.

Sama-Bajau

The term Sama-Bajau is used to describe a diverse group of Sama-Bajau-speaking people who are found in a large maritime area with many islands that stretch from central Philippines to the eastern coast of Borneo and from Sulawesi to Roti in eastern Indonesia. The Sama-Bajau people usually call themselves the Sama or Samah (formally A'a Sama, "Sama people") and have traditionally been known by outsiders as Bajau (also spelled Badjao, Bajaw, Badjau, Badjaw, Bajo or Bayao). They have also been Sea Gypsies, Sea Nomads and Samal as well as Sama Moro and Turijene in the Philippines, Luwa’an, Pala’au, Sama Dilaut and Turijene in Indonesia, and the Bajau Laut in Malaysia. Some of these names refer to Sama-Bajua subgroups. [Source: Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Sama-Bajau speakers are probably the most widely dispersed indigenous ethnolinguistic group in Southeast Asia. Their settlements are scattered throughout the central Philippines, the Sulu Archipelago, the eastern coast of Borneo, Palawan, western Sabah (Malaysia), and coastal Sulawesi. They also have small enclaves in Zambales and northern Mindanao. In the Philippines, most Sama speakers are referred to as "Samal," a Tausug term also used by Christian Filipinos, with the exceptions of Yakan, Abak, and Jama Mapun. In Indonesia and Malaysia, related Sama-speaking groups are known as "Bajau," a term of apparent Malay origin. In the Philippines, however, the term "Bajau" is more narrowly reserved for boat-nomadic or formerly nomadic groups referred to elsewhere as "Bajau Laut" or "Orang Laut."

For most of their history, the Sama-Bajau have been nomadic seafaring people who live off the sea through trade and subsistence fishing. They have traditionally stayed close to shore with houses on stilts and traveled, and sometimes lived in, handmade boats lepa. Sama-Bajau are the dominant ethnic group in Tawi-Tawi islands and are generally associated with the Sulu islands, the southernmost islands of the Philippines. They are also found in the coastal areas of Mindanao and other islands in the southern Philippines, as well as in northern and eastern Borneo, Sulawesi, and throughout the eastern Indonesian islands. Most Sama-Bajau are Muslims. In the Philippines, they are grouped with the Moro people, who have similar religious beliefs. Some Sama-Bajau groups native to Sabah are also known for their traditional horse culture. The Orang Laut and Moken are two other traditional sea-based peoples. The Orang Laut have traditionally lived southern peninsular Malaysia, southeastern Sumatra and Singapore. The Moken live in southern Myanmar and western Thailand.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SAMA-BAJUA SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJUA LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Ethnic Groups in Poso Area of Central Sulawesi

The Poso region of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, is characterized by significant ethnic diversity shaped by both indigenous communities and migrant populations. The largest indigenous group is the Pamona, many of whom live in the highlands around Lake Poso, with Tentena serving as an important cultural center. The Pamona are predominantly Protestant Christian. Other indigenous groups in the region include the Lore peoples—comprising the Bada, Behoa, Napu, and Tawailia subgroups—as well as the Mori, Tojo, Bungku, Kaili, and Wana.

Alongside these indigenous communities, Poso has long attracted migrants, many of whom are Muslim and tend to settle in coastal areas and the town of Poso itself. Major migrant groups include the Bugis, Javanese, Mandar, and Makassar, along with smaller populations of Minahasa, Toraja, Balinese, and Maluku peoples. Some of these migrants arrived through government-sponsored transmigration programs, while others came independently in search of trade and economic opportunities.

The Poso conflict largely involved tensions between indigenous Christian communities—especially the Pamona—and predominantly Muslim migrant groups, particularly Bugis and Javanese settlers from South Sulawesi and Java. Indigenous groups drawn into the conflict included the Pamona, Lore, Mori, and communities from Kulawi, Napu, Behoa, and Bada, while Catholic migrants from Flores were also involved in some Christian militias. On the Muslim side were Bugis, Javanese, Gorontalo, and migrants from Maluku, Kaili, Mandar, and other regions.

Although the violence was often framed in religious terms, its roots lay in deeper economic, political, and ethnic tensions. Many indigenous communities felt increasingly marginalized by the economic success and growing political influence of migrant populations. These long-standing grievances intensified in the political vacuum following the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, ultimately erupting into a prolonged and destructive communal conflict.

See Separate Article: MUSLIM-CHRISTIAN VIOLENCE IN INDONESIA IN POSO, SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

Pamona

The Pamona people are the main ethnic group of the Poso and Lake Poso area of Central Sulawesi. Also known as Bare’e, To Pamona and Poso, they inhabit most of Poso Regency, as well as parts of Tojo Una-Una and North Morowali regencies, with smaller communities in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, and elsewhere in Indonesia. Oral tradition traces their origins to Salu Moge in East Luwu, from where they were resettled closer to centers of authority before later dispersing more widely, particularly during periods of conflict such as the DI/TII rebellion. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Pamona are predominantly Christian, with Christianity introduced in the late nineteenth century and widely adopted. Today, most Pamona churches belong to the Central Sulawesi Christian Church, headquartered in Tentena. A small minority practices Islam. Pamona people commonly speak the Pamona language alongside Indonesian, often mixed with local slang, and work as farmers, civil servants, pastors, traders, and entrepreneurs. The Christian group [Source: Joshua Project estimated their population to be around 186,000 in the early 2020s and figured 93 percent of them are Christians, with Evangelical accounting for 5 to 10 percent of that number.

Anthropologically, “Poso” refers to a geographic region rather than a distinct ethnic group; its indigenous population is Pamona. Local explanations of the name Poso vary, linking it either to words meaning “break” or “bind,” both connected to origin stories surrounding Lake Poso and the settlement of its shores. Over time, the lake and river system became central to Pamona identity and settlement patterns.

The term Pamona also denotes a broader customary alliance, derived from Pakaroso Mosintuwu Naka Molanto, later formalized under Dutch colonial administration. Pamona customary institutions persist today in both Poso and Luwu regions, maintaining traditional leadership structures and cultural continuity. Culturally, the Pamona are known for their rich oral traditions and communal dances, especially the Dero (or Madero) dance, a circular dance accompanied by song and poetry, traditionally associated with agricultural cycles, festivals, and social interaction among youth.

Eastern Toraja

The Eastern Toraja live mainly around Lake Poso and in the valleys of the Poso, Laa, and Kalaena rivers in Central Sulawesi. They are also known as the Bare’e, Oost-Toradja, Poso-Todjo, Re’e speakers, To Lage, and Toradja Timur. Their territory is bordered by the Western Toraja to the west, the Mori and Loinang peoples to the east, the Gulf of Tomini to the north, and the former Buginese kingdom of Luwu to the south. North Toraja Regency had an estimated population of about 260,000 in 2023, of which Eastern Torajans made up a large share but exactly how large is not clear. Earlier estimates for the Eastern Toraja population were about 30,000 in 1930, 60,000 in 1935, and 100,000 in 1961, [Source: John Beierle and Martin J. Malone, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1996]

The Bare’e language, spoken by the Eastern Toraja with only dialect differences, belongs to the Toraja language group within the Central and Southern Celebes cluster, mainly a geographical grouping, of Austronesian languages. Toraja populations are commonly divided into Western, Eastern, and Southern branches, each reflecting different levels of influence from Hindu-Javanese states in southwestern Sulawesi and from Borneo (LeBar 1972). The Eastern, or Bare’e-speaking, Toraja consist of many local groups with a largely shared language and culture. They form several regional clusters: 1) the Poso-Todjo groups along the Gulf of Tomini and the neck of the eastern peninsula; 2) groups around Lake Poso; 3) groups in the upper Laa Valley east of Lake Poso; and 4) groups in the upper Kalaena region south of Lake Poso. The To Wana and To Ampana peoples east of Lake Poso, although once included among the Eastern Toraja, are better treated as separate groups because of linguistic, physical, and cultural differences; they speak Taa or Tae’ rather than Bare’e.

The Eastern Toraja traditionally practice dry-rice agriculture. Wet-rice cultivation was introduced by the Dutch after 1905 but remained limited. Maize is the second most important crop and is eaten mainly when rice supplies are low. Millet, Coix agrestis, fruits, and vegetables are also grown using swidden farming. Hunting and fishing, especially around Lake Poso, contribute to subsistence.

Weaving is limited, but bark cloth (foeja or fuya) production is well developed. Other crafts include basketry, mat making, pottery, dugout canoe construction, and copper and brass working. Ironworking is especially important; each village traditionally has at least one smith. Iron is believed to possess strong spiritual power, requiring annual rituals to neutralize it and prevent illness attributed to the smithy spirit.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Eastern Toraja: Summary e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026