ASIAN ANIMALS AND BIODIVERSITY IN ASIA

some of the animals found in Asia

Scientists sometimes break down the world’s animals into Old World animals — those from Asia, Africa and Europe — and New World animals — those from North and South America. Australia, New Zealand and many islands have their own species.

The Old World and New World designations have traditionally been used mostly to describe monkeys but has also been used for other animal groupings. Some Old World species are found over large areas of Asia, Africa and Europe. Most are found only in certain regions. Old World species within an animal grouping tend to be more closely related to each other than to New World species in the same grouping.

Until man began transporting animals around the globe the only way that animals could move between the Old and New Worlds was by walking across the Bering Strait or the Arctic or by swimming or floating on some flotsam across the sea. By contrast, Old World animals could move easily overland between Asia, Africa and Europe, which explains in part why Old World species are more closely related to each other than they are to their New World counterparts.

Asia has more endangered species than any other continent, with over 16,000 species listed as endangered, critically endangered, or vulnerable:

In Asian rainforest you can find gliding snakes, frogs, squirrels, geckos and other lizards. One theory as to why there are so many aerial species in Asian forests is that the trees are generally taller than those in Africa and the Americas and they are not joined together as well by woody vines called lianas and thus webbed feet and gliding flaps provide an efficient means to get from tree to tree.

Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Wallace Line

The Wallace Line is an invisible biological barrier described by and named after the British naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace (See Below). Running along the water between the Indonesia islands of Bali and Lombok and between Borneo and Sulawesi, it separates the species found in Australia, New Guinea and the eastern islands of Indonesia from those found in western Indonesia, the Philippines and the Southeast Asia.

The Wallace Line was drawn in 1859 by Wallace and named by the English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley. It separates the biogeographic realms of Asia and 'Wallacea', a transitional zone between Asia and Australia formerly also called the Malay Archipelago and the Indo-Australian Archipelago (Present day Indonesia). To the west of the line are found organisms related to Asiatic species; to the east, a mixture of species of Asian and Australian origins is present. Wallace noticed this clear division in both land mammals and birds during his travels through the East Indies in the 19th century. [Source: Wikipedia]

Wallace Line

Because of the Wallace Line Asian animals such as elephants, orangutans and tigers never ventured further east than Bali, and Australian animals such as kangaroos, emus, cassowaries, wallabies and cockatoos never made it to Asia. Animals from both continents are found in some parts of Indonesia.

Wallace came up with the idea of a dividing line for animals after conducting surveys in the 1850s in Borneo and Sulawesi, where he was struck by how different the wildlife was on the two islands despite their close proximity to one another and their similar climates and geography. His letters to Darwin on the subject prompted Darwin to take a look as his own travels and make similar observations on some of the places he visited. In 1859 Wallace expanded on his observations and drew a line between Borneo and Bali to the west and Sulawesi and Lombok to the east and theorized that areas to the west — including the islands of Indonesia the Philippines — were part of a great Asian landmass and areas to east were connected to a greater Australian landmass, with Sulawesi containing elements of both the Asian and Australian landmass.

Studies of geology, ice ages and rising and falling sea levels conducted after Wallace’s death — that among other things found that Indonesia, the Philippines and the Southeast Asia were all connected by land bridges when sea levels dropped during ice ages — proved that his theories were largely correct. Further studies on the matter placed the furthest extent of Australian type fauna further east between the Moluccas and Timor.

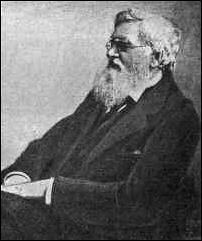

Alfred Russell Wallace

Alfred Russell Wallace

Alfred Russell Wallace (1823-1913) developed a theory of evolution the same time as Darwin but failed to win the same recognition as Darwin. He made a historic journey through Malaysia, Borneo and Spice Islands about 20 years after Darwin made his voyage in the Beagle. Wallace was a much more colorful character than Darwin. He was one of nine children in a poor family and dropped out of school at fourteen. His interest in the natural sciences blossomed during beetle-hunting expeditions with a close friend.

Wallace spent fours years collecting specimens in the Amazon. He wrote a paper entitled On Monkeys in the Amazon but lost his specimens when the ship he was on caught fire and sunk on the voyage back to Europe. Later in life he became a vocal supporter of women's rights and was a firm believer in Spiritualism. He disputed a theory that the canals on the planet Mars were used by irrigation in his treatise “Is Mars Habitable?”

Wallace was a professional specimen collector. He spent much of his life far from civilization, in remote jungles and isolated islands. He collected 125,000 species of flora and fauna, many of them new to science, during his five years in Amazon basin and eight years traveling alone in Indonesia. The idea of survival of the fittest came to him while he was suffering from a malaria fit. Austen Layard, a contemporary of Wallace, said "one of the results of fever is a considerable excitement of the brain."

See Wallace in Indonesia and Malaysia Under WILDLIFE IN INDONESIA: RARE, UNIQUE AND ENDANGERED ANIMALS factsanddetails.com ; DARWIN factsanddetails.com; ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE ON BIRDS OF PARADISE factsanddetails.com

Weber’s Line and Lydekker’s Line

The Weber line is named after Max Wilhelm Carl Weber (1852 –1937), a German-Dutch zoologist and biogeographer. His discoveries as leader of the Siboga Expedition (a Dutch zoological and hydrographic expedition to Indonesia in 1899 and 1900) led him to conclude that Wallace's Line was placed too far to the west. His studies, along with others, led to a series of alternative lines delimiting the Australasian realm from the Indomalayan realm. These lines were based on the fauna and flora in general, including the mammalian fauna. [Source: Wikipedia]

Later, Pelseneer published an influential paper on this topic, in which he proposed his preferred limit Weber's Line., to honor Weber. As is the case with plant species, faunal surveys revealed that for mollusks and most vertebrate groups Wallace’s line was not the most significant biogeographic boundary. The Tanimbar Island group, and not the boundary between Bali and Lombok, appears to be the major interface between the Asia and Australasian regions for mammals and other terrestrial vertebrate groups.

Lydekker’s Line is named after Richard Lydekker (1849–1915), a British naturalist, geologist and writer. In 1896 he delineated the biogeographical boundary through Indonesia, known as Lydekker's Line, that separates Wallacea on the west from Australia-New Guinea on the east. It follows the edge of the Sahul Shelf, an area from New Guinea to Australia of shallow water with the Aru Islands on its edge. Along with Wallace's Line and others, it indicates the definite effect of geology on the biogeography of the region, something not seen so clearly in other parts of the world.

Sundaland Biodiversity Hotspot

The Sundaland region, which include peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali, has been designated a biodiversity hotspot designated by Conservation International. According to the Conservation International website: “The spectacular flora and fauna of the Sundaland Hotspot are succumbing to the explosive growth of industrial forestry in these islands and to the international animal trade that claims tigers, monkeys, and turtle species for food and medicine in other countries. Populations of the orangutan, found only in this hotspot, are in dramatic decline. Some of the last refuges of two Southeast Asia rhino species are also found on the islands of Java and Sumatra. Like many tropical areas, the forests are being cleared for commercial uses. Rubber, oil palm, and pulp production are three of the most detrimental forces facing biodiversity in the Sundaland Hotspot.[Source: Conservation International website]

Data: 2) Hotspot Original Extent (km²): 1,501,063; 2) Hotspot Vegetation Remaining (km²): 100,571; 3) Endemic Plant Species: 15,000; 4) Endemic Threatened Birds: 43; 5) Endemic Threatened Mammals : 60; 6) Endemic Threatened Amphibians; 59; 7) Extinct Species: 4; 8) Human Population Density (people/km²): 153; 9) Area Protected (km²) 179,723; 10) Area Protected (km²) in Categories I-IV 77,408.

The Sundaland hotspot covers the western half of the Indo-Malayan archipelago, an arc of some 17,000 equatorial islands, and is dominated by two of the largest islands in the world: Borneo (725,000 km²) and Sumatra (427,300 km²). More than a million years ago, the islands of Sundaland were connected to mainland Asia. As sea levels changed during the Pleistocene, this connection periodically disappeared, eventually leading to the current isolation of the islands. The topography of the hotspot ranges from the hilly and mountainous regions of Sumatra and Borneo, where Mt. Kinabalu rises to 4,101 meters, to the fertile volcanic soils of Java and Bali, the former dominated by 23 active volcanoes. Granite and limestone mountains rising to 2,189 meters are the backbone of the Malay Peninsula.

Politically, Sundaland covers a small portion of southern Thailand (provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat); nearly all of Malaysia (nearly all of Peninsular Malaysia and the East Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah in northern Borneo); Singapore at the tip of the Malay Peninsula; all of Brunei Darussalam; and all of the western half of the megadiversity country of Indonesia, including Kalimantan (the Indonesian portion of Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and Bali). The Nicobar Islands, which are under Indian jurisdiction, are also included.

Sundaland is bordered by three hotspots. The boundary between the Sundaland Hotspot and the Indo-Burma Hotspot to the northwest is here taken as the Kangar-Pattani Line, which crosses the Thailand-Malaysia border. Wallacea lies immediately to the east of the Sundaland Hotspot, separated by the famous Wallace’s Line, while the 7,100 islands of the Philippines Hotspot lie immediately to the northeast.

Lowland rainforests are dominated by the towering trees of the family Dipterocarpaceae. Sandy and rocky coastlines harbor stands of beach forest, while muddy shores are lined with mangrove forests, replaced inland by large peat swamp forests. In some places, ancient uplifted coral reefs support specialized forests tolerant of the high levels of calcium and magnesium in these soils. Infertile tertiary sandstone ridges support heath forest. Higher elevations boast montane forests thick with moss, lichens, and orchids, while further up, scrubby subalpine forests are dominated by rhododendrons. At the very tops of the highest mountain peaks, the land is mostly rocky and without much vegetation.

Wallace map

Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot

The Indo-Burma region, which includes far-east India, far-southern China and most of mainland Southeast Asia excluding the Malaysian peninsula, has been designated a biodiversity hotspot designated by Conservation International. According to the Conservation International website: Indo-Burma is still revealing its biological treasures. Six large mammal species have been discovered in the last 12 years: the large-antlered muntjac, the Annamite muntjac, the grey-shanked douc, the Annamite striped rabbit, the leaf deer, and the saola. This hotspot also holds remarkable endemism in freshwater turtle species, most of which are threatened with extinction, due to over-harvesting and extensive habitat loss. Bird life in Indo-Burma is also incredibly diverse, holding almost 1,300 different bird species, including the threatened white-eared night-heron, the grey-crowned crocias, and the orange-necked partridge. [Source: Conservation International website]

Indo-Burma (Southeast Asia) has been designated a biological hot spot because it is rich in unique wildlife and plant life but also threatened by the encroachment of people. Data: 1) Hotspot Original Extent (km²): 2,373,057; 2) Hotspot Vegetation Remaining (km²): 118,653; 3) Endemic Plant Species: 7,000; 4) Endemic Threatened Birds: 18; 5) Endemic Threatened Mammals: 25; 6) Endemic Threatened Amphibians: 35 ; 7) Extinct Species: 1; 8) Human Population Density (people/km²): 134 ; 9) Area Protected (km²): 235,758; 10) Area Protected (km²) in Categories I-IV: 132,283.

The Indo-Burma hotspot encompasses 2,373,000 km² of tropical Asia east of the Ganges-Brahmaputra lowlands. Formerly including the Himalaya chain and the associated foothills in Nepal, Bhutan and India, the Indo-Burma hotspot has now been more narrowly redefined as the Indo-Chinese subregion. The hotspot contains the Lower Mekong catchment. It begins in eastern Bangladesh and then extends across north-eastern India, south of the Bramaputra River, to encompass nearly all of Myanmar, part of southern and western Yunnan Province in China, all of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia and Vietnam, the vast majority of Thailand and a small part of Peninsular Malaysia. In addition, the hotspot covers the coastal lowlands of southern China (in southern Guangxi and Guangdong), as well as several offshore islands, such as Hainan Island (of China) in the South China Sea and the Andaman Islands (of India) in the Andaman Sea. The hotspot containes the Lower Mekong catchment.

The transition to the Sundaland Hotspot in the south occurs on the Thai-Malay Peninsula, the boundary between the two hotspots is represented by the Kangar-Pattani Line, which cuts across the Thailand-Malaysia border, though some analyses indicate that the phytogeographical and zoogeographical transition between the Sundaland and Indo-Burma biotas may lie just to the north of the Isthmus of Kra, associated with a gradual change from wet seasonal evergreen dipterocarp rainforest to mixed moist deciduous forest.

Much of Indo-Burma is characterized by distinct seasonal weather patterns. During the northern winter months, dry, cool winds blow from the stable continental Asian high-pressure system, resulting in a dry period under clear skies across much of the south, center, and west of the hotspot (the dry, northeast monsoon). As the continental system weakens in spring, the wind direction reverses and air masses forming the southwest monsoon pick up moisture from the seas to the southwest and bring abundant rains as they rise over the hills and mountains.

A wide diversity of ecosystems is represented in this hotspot, including mixed wet evergreen, dry evergreen, deciduous, and montane forests. There are also patches of shrublands and woodlands on karst limestone outcrops and, in some coastal areas, scattered heath forests. In addition, a wide variety of distinctive, localized vegetation formations occur in Indo-Burma, including lowland floodplain swamps, mangroves, and seasonally inundated grasslands.

Borneo

Southeast Asian Rain Forest at Night

Tim Laman wrote in National Geographic: “As the day's last light paints the tropical sky, I perch on the side of a cliff on Khao Luk Chang (Baby Elephant Mountain) in Thailand. A few feet in front of me thousands of wrinkled-lipped bats stream out of their cave. Soon they will fan out and gorge on insects in the forest below. Human eyes that work so well during the day are of little use in this world. Out here, hosts of species are supremely adapted for making a living in the dark. Bats with their sonar, tarsiers with their acute hearing and night vision, and civets with their exquisite sense of smell are just a few examples. I wish my senses were a match for these nocturnal creatures. Though limited to my human perception, I do get a little help from technology. With headlamps, strobes, infrared camera traps, and night-vision scopes in my arsenal, I head off into the rain forest after dark. It's as rich in life as it is by day but with an almost completely different cast of characters. [Source: Tim Laman, National Geographic. October 2001]

“I have photographed creatures of the night in rain forests across tropical Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. African and South American rain forests host a similarly rich assortment of little-known inhabitants. Of these three equatorial regions, Asia is losing its forests the fastest and has the fewest remaining. In Indonesia alone, illegal logging has led to what one scientific report called a "biological catastrophe."Whether I am strolling along a forest track, where I spotted this spiky caterpillar chomping on a wild ginger leaf, or making an exploratory night climb with colleagues into the top of Borneo's forest canopy of dipterocarp trees, the night has many surprises in store for me. Few people have ever experienced them, and unless we protect enough pristine forest, few ever will. If we act quickly to preserve what remains, generations to come will still be able to appreciate the wonders of the rain forest's night shift.

“What goes in must come out, but rarely does animal waste look so graceful. This plant hopper nymph feeds on plant juices with a tubelike mouth. The long fibers that appear to form a tail are the waxy residue of sugars discharged after the hopper extracts nutrients from sap. Glands arranged like a spaghetti press push out the filaments, composed of microscopic hollow tubes. These filaments may deter predators, or they may simply break away if a predator tries to grab the false tail. Whether they have tricky defenses or not, many insects find that night is the safest time. A dragonfly uses the cover of darkness to emerge from its larval skin and dry its wings. It will be able to fly by morning, but several days will pass before its body fully hardens and develops characteristic bright colors.

“The night is a time for carnivores of many tastes. As odd as its name, the moonrat is not really a rat but part of the hedgehog family. Although some are black with white markings, those found on Borneo are predominantly white. Their conspicuous coloring and bad odor advertise a repulsive taste to predators, so they are often left alone to hunt for earthworms, insects, and snails amid the leaf litter. The cat snake, one of hundreds of kinds of snakes active mostly at night, moves through low vegetation to hunt frogs and lizards. Asian wild dogs, or dholes, prey on large game such as this sambar deer they killed at the edge of a river in Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. Once widespread across Asia, large numbers of these pack-hunting canids have been exterminated by locals, who perceive them as a threat to livestock. They are now reduced to remnant populations even in protected areas.

“Wide eyes blazing in the light of my camera flash, a brown wood owl poises on a forest perch. Excellent night vision helps owls fly through the dark forest, but, like tarsiers, owls also rely on their highly sensitive hearing to detect and capture a variety of prey: small rodents, lizards, frogs, even large insects. Well-camouflaged moths survive the daylight hours by blending in with a background such as dead leaves or bark. By night they use their sense of smell—detectors built into their antennae—to locate mates and food. One evening as I entered the forest, I smelled a heady perfume coming from flowers opening to attract small moths. Like many night-blooming plants, this orchid has pale flowers that are easy to spot in low light. Pollinators home in on the flowers' scent from a distance and then use their vision to make the final approach.

No matter how closely you approach a Bornean horned frog, it won't budge. It acts as if its camouflage makes it invisible, and it very nearly does. Finding one is extremely difficult. In this case the reflection of its eyes in my headlamp beam gave it away. With a mouth as wide as half its body length, the horned frog simply waits for prey to pass by, and a large spider like this leggy tarantula emerging from its webbed retreat would make a fine meal. The Malay civet actively forages for anything edible. A bait of fish lured it to this site in Gunung Palung National Park, Indonesia, where it tripped my remote-controlled camera. Unfortunately Gunung Palung, like many parks in Indonesia, is now being devastated by illegal logging, and there seems to be little political means or will to stop it.

“As long as these forests remain intact, every night walk can reveal new marvels. A snail exploring a leaf performs a nimble pirouette at the tip. Perched on a twig where it can detect a predator's approach, a garnet pitta sleeps through the night. The pitta, like many other diurnal birds, adds insurance while sleeping by fluffing up so much that an attacking snake might get only a mouthful of feathers. On a moonless, overcast night I turn off my headlamp and stand among the towering trees of Borneo's lowland forest. At first it seems as black as the deepest cave, but as my eyes adjust, I see that the forest has some light of its own. Patches of luminescent fungi are visible, and a bright point of light nearby turns out to be a strange beetle larva called a starworm crawling among fallen leaves. Why does the starworm produce its steady glow? Could it be seeking mates? Luring prey? Alerting predators that it is inedible? For now it remains one of the many mysteries of the rain forest at night.

Borneo Rainforests Full of Rare Species

Diyan Jari and Reuben Carde of Reuters wrote: “About three years ago, wildlife researchers photographed a mysterious fox-like mammal on the Indonesian part of Borneo island. They believed it was the first discovery of a new carnivore species there in over a century. Since then, more new species of plants and animals have been found and conservationists believe Borneo, the world’s third-largest island, is a treasure trove of exotic plants and animals waiting to be discovered. [Source: Diyan Jari and Reuben Carder, Reuters, March 29, 2006 \~/]

“The new finds were all the more remarkable after decades of deforestation by loggers, slash-and-burn farming, creation of vast oil palm plantations, as well as rampant poaching. Conservationists hope that Borneo will reveal many more secrets, despite the myriad threats to its unique flora and fauna. “There is vast potential,” said Gusti Sutedja, WWF Indonesia’s project director for Kayan Mentarang national park, a sprawling reserve on the island where the new mammal, nicknamed the Bornean Red Carnivore, was photographed in a night-time camera trap. The animal itself is so rare, it’s never been captured. \~/

“In 2003, we conducted joint operations with Malaysian scientists and discovered many unknown species of lower plants. Three frogs discovered are being tested by German researchers. We also recorded five new birds in a forest survey in 2003.” Some conservationists believe Borneo could be the next “Lost World” after the recent discovery of a host of butterflies, birds and frogs in another Indonesian jungle on the island of New Guinea.” \~/

Borneo has more species of tree shrew than anywhere else on the world. Tree shrews are not shrews and most species do not live in trees. They are generally hyper creatures that belong to their owner order (Scandentia). The local Bahasa Indonesian word for them, “tupai”, is the same word used for squirrels.

See Separate Article: ANIMALS OF BORNEO factsanddetails.com

Mekong River Biodiversity and Life

The Mekong River is home of rare Irrawaddy river dolphins and rare pla buk, the world's largest freshwater fish, the Mekong Giant Catfish. By one count only around 100 river dolphins are left and they are mostly in northern Cambodia. But at the same time fish caught in the river are an important source of protein for an estimated 65 million people.

Jeremy Hance wrote in mongabay.com, “Home to giant catfish and stingrays, feeding over 60 million people, and with the largest abundance of freshwater fish in the world, the Mekong River, and its numerous tributaries, brings food, culture, and life to much of Southeast Asia. Despite this, little is known about the biodiversity and ecosystems of the Mekong, which is second only to the Amazon in terms of freshwater biodiversity. Meanwhile, the river is facing an existential crisis in the form of 77 proposed dams, while population growth, pollution, and development further imperil this understudied, but vast, ecosystem. More than 850 species have been described. [Source: Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com, April 23, 2013 |~|]

The Mekong river is home to around 850 species of freshwater fish, many of which are only found in the region, and a host of other animals. Researchers estimate there could be over 1,200 fish species in Mekong River. Eleanor J. Sterling and Merry D. Camhi wrote in Natural History magazine, “That mesh of waterways is one of the most productive and diverse ecosystems on Earth, supporting more than 6,000 species of vertebrates alone. Its fish fauna, with some 2,000 species, of which sixty-two are endemic, exceeds all but those of the Amazon and Congo river basins. The wetlands harbor several threatened and endangered birds and mammals, including the eastern sarus crane, Grus antigone sharpii; the Bengal florican, Houbaropsis bengalensis; and the hairy-nosed otter, Lutra sumatrana, which was recently rediscovered after having been feared extinct. Sixty-five million people live there, too, 80 percent of them dependent on the river for their livelihood as farmers and fishers. [Source: Eleanor J. Sterling and Merry D. Camhi, Natural History magazine, December 2007]

See Separate Article: MEKONG RIVER BIODIVERSITY AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025