WILDLIFE IN INDONESIA

Indonesia is one of the world’s great reservoirs of natural life. Many animals such as the Javan rhinoceros, Komodo dragon and several species of bird of paradise are found nowhere else in the world. Some 430 of Indonesia's bird species and 200 of its mammals as well as hundreds of reptiles and amphibians are unique to the archipelago. [Source: National Geographic]

Unusual animals on Java include mudskippers, a tree climbing fish; huge, hairy bird spiders that can walk on water; and the monstrous Atlas moth, which has wing tips that resemble the head of golden-banded mangrove snake, a venomous species that birds, the moth major enemy, stay clear of. Crocodiles and poisonous snakes are present throughout Indonesia, although only very common in a few areas. Komodo dragons can be very dangerous if harassed, but are only found on Komodo and a few neighboring islands. [Source: Diter and Mary Plage, National Geographic, June 1985]

Indonesia is one of the world's most biodiverse countries. By one count it is home to over 300,000 wildlife species (mostly insects and microorganisms), including 31,750 plant species, and 5,142 tree species, the third most in the world. Indonesia has 732 mammal species, including the Sumatran tiger, Sumatran elephant, and Sumatran rhinoceros, 1,711 bird species, 750 reptile species, 403 amphibian species and 1,236 freshwater fish species. Marine biodiversity in Indonesia is reflected by over 574 coral species and 45 mangrove species. [Source: Google AI]

Indonesia’s wildlife varies from the Java mouse deer (or kancil) to one-horned rhino to the the Sulwesi anoa (a small water buffalo). Some animals are new. Monkeys, pigs and dogs were brought to Flores about 4,000 years ago. Some are endangered. Populations of sun bears, flying squirrels, and birds such as kingfishers, trogons and forktails have declined in areas of Borneo and Sumatra that have been logged.

Books: “Wildlife of Indonesia” by Kathy MacKinnon; “Wild Indonesia” by Tony and June Whitten.

Why Wildlife in Indonesia is So Plentiful and Diverse

Wildlife in Indonesia so abundant and diverse because the tropical climate and rich soil support a wide range of flora and fauna. Mangrove swamps and marshes flourish along the coast; tropical rain forests cover most of the terrain up to 3,000 feet; and abundant subtropical vegetation, such as oak, pine, and hardwoods, thrives at higher altitudes. The abundant forest cover and favorable climate have stimulated a diverse animal life.

Wallace Line

Indonesia lies on the Equator, and is hot and humid throughout the year. Rainfall is generally heavy; only the Sunda Islands have a dry season. Minerals found on land and in the sea caused by volcanic eruptions, have made this the ideal habitat for a large number of unique and endemic species. [Source: Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy, Republic of Indonesia]

Because there are so many islands and on the islands the landcape is often rugged, thousands of new species have develop in isolated spots. Plant life is a mix of Asiatic and Australian forms with endemic ones. Vegetation ranges from that of the tropical rain forest of the northern lowlands and the seasonal forests of the southern lowlands, through vegetation of the less luxuriant hill forests and mountain forests, to subalpine shrub vegetation. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Each island has its own peculiar types of wildlife. Orangutans and elephants are found in Sumatra and Kalimantan on Borneo. but not in Java.. All the islands, especially the Malukus, abound in great varieties of bird life, reptiles, and amphibians.

Wallace Line

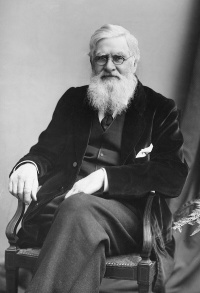

Indonesia’s flora and fauna is divided by the “Wallace Line”. The Wallace Line is an invisible biological barrier described by and named after the British naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace (See Below). Running along the water between the Indonesia islands of Bali and Lombok and between Borneo and Sulawesi, it separates the species found in Australia, New Guinea and the eastern islands of Indonesia from those found in western Indonesia, the Philippines and the Southeast Asia.

In Indonesia the Wallace Line runs between Bali and Lombok, continuing north between Kalimantan and Sulawesi. West of the Line, vegetation and wildlife are Asian in nature, whereas east of the Line, these resemble those of Australia. The animals of Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Java west of the Wallace Line are similar to those found on Peninsular Malaysia.In Sulawesi, the Maluku Islands, and Timor, east of the Wallace Line, Australian types begin to occur. Bandicoot, a marsupial, is found in Timor. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007; Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy, Republic of Indonesia]

For more information on the Wallace Line See BIODIVERSITY IN SOUTHERN ASIA: WALLACE LINE, HOTSPOTS, RARE SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Wallace in Indonesia and Malaysia

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Alfred Russel Wallace was a great English biologist and magnificent Victorian obsessive, who embraced spiritualism and opposed vaccinations, colonialism, exotic feathers in women’s hats, and unlike most of his contemporaries, saw native peoples without the gaze of racial superiority. An evolutionary theorist, he was first upstaged, then totally overshadowed by his more ambitious colleague Charles Darwin.[Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, April 2018]

“Beginning in 1854, Wallace spent eight years in the Malay Archipelago (now Malaysia and Indonesia), observing wildlife and paddling up rivers in pursuit of the most sought-after creature of the day: the bird of paradise. Decked out in strange quills and gaudy plumage, the male has developed spectacular displays and elaborate courtship dances whereby he morphs into a twitching, lurching geometric abstraction. Inspired by bird of paradise sightings — and reputedly while in a malarial fever — Wallace formulated his theory of natural selection.

By the time he left Malay, he had depleted the ecosystem of more than 125,000 specimens, mainly beetles, butterflies and birds — including five species from the bird of paradise family. Much of what Wallace had accumulated was sold to museums and private collectors. His field notebooks and thousands of preserved skins are still part of a continuous voyage of discovery. Today the vast majority of Wallace’s birds repose at a branch of the Natural History Museum, London, located 30 miles northwest of the city, in Tring. The facility also houses the largest zoological collection amassed by one person: Lord Lionel Walter Rothschild (1868-1937), a banking scion said to have almost exhausted his share of the family fortune in an attempt to collect anything that had ever lived.

For more information on Wallace See BIODIVERSITY IN SOUTHERN ASIA: WALLACE LINE, HOTSPOTS, RARE SPECIES factsanddetails.com ; DARWIN factsanddetails.com; ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE ON BIRDS OF PARADISE factsanddetails.com

Sundaland and Wallacea

Western Indonesia is part of Sunderland, so named because Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Bali and Malaysia and much of Southeast Asia lie on the Sundra Shelf and are called the Greater Sundra Island. Eastern Indonesia is sometimes referred to as Wallacea. Sunderland and Wallacea have been designated biological hot spots because of their rich in unique wildlife and plant life and because these are threatened by the encroachment of people. For more information on Sunderland See BIODIVERSITY IN SOUTHERN ASIA: WALLACE LINE, HOTSPOTS, RARE SPECIES factsanddetails.com

According to Conservation International: “The flora and fauna of Wallacea are so varied that every island in this hotspot needs secure protected areas to preserve the region’s biodiversity. The hotspot is second only to the Tropical Andes in terms of bird endemism, which is particularly impressive given its relatively small land area. The world’s largest lizard, the Komodo dragon, is restricted to the islands of Komodo, Padar, Rinca, and Flores in the Wallacea hotspot. Unfortunately, Wallacea's forests have been cleared at increasing rates as a result of the growing population. A deforestation problem that is somewhat unique to this region was caused by the government sponsored transmigration program, which was proposed to solve overcrowding on highly populated islands by moving large numbers of people to sparsely inhabited areas. [Source: Conservation International]

VITAL SIGNS: Hotspot Original Extent (square kilometers): 338,494; Hotspot Vegetation Remaining (square kilometers): 50,774; Endemic Plant Species: 1,500; Endemic Threatened Birds: 49; Endemic Threatened Mammals: 44; Endemic Threatened Amphibians: 7; Extinct Species†: 3; Human Population Density (people/square kilometers): 81; Area Protected (square kilometers): 24,387; Area Protected (square kilometers) in Categories I-IV*: 19,702; †Recorded extinctions since 1500. *Categories I-IV afford higher levels of protection.

“The Wallacea hotspot encompasses the central islands of Indonesia east of Java, Bali, and Borneo, and west of the province of New Guinea, and the whole of Timor Leste. The hotspot, which occupies a total land area of 338,494 square kilometers, includes the large island of Sulawesi and also the Moluccas, or Spice Islands, and the Lesser Sundas (which encompasses Timor Leste, and the Indonesia region of Nusa Tenggara).

“Wallacea is divided from Sundaland, the other hotspot found in Indonesia, by Wallace's Line, which separates the Indo-Malayan and Australasian biogeographic realms. The line and the hotspot are both named for the 19th century English explorer and naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who identified the distinctiveness of faunas on either side of the line.

“In terms of vegetation, Sulawesi and the Moluccas are largely tropical rainforest, but in many parts of the Lesser Sundas, rainforest formations are found only at high elevations and in areas facing the rain-bearing winds, while significant areas are covered in savanna woodland, including some Eucalyptus forests. In some lowland areas, such as in eastern Sulawesi, there are unusual and infertile ultrabasic soils with high concentrations of iron, magnesium, aluminum, and heavy metals. The lowland forests on these nutrient-poor ultrabasic soils have rather short trees, and appear to be dominated by the myrtle family

Wallace in Wallacea

Andrew Berry, a lecturer on evolutionary biology at Harvard University, told the New York Times that Wallace targeted places that were remote and geologically unusual during his exploration of Southeast Asia from 1854 to 1862. [Source: Karen Weintraub, New York Times, January 9, 2020]

Karen Weintraub wrote in the New York Times: Wallace described nearly two percent of all known bird species during his time there, Dr. Berry said, conducting the kind of basic descriptive biology that undergirds this new research. “Identifying new species might seem unsexy, the scientific equivalent of stamp collecting,” Dr. Berry said. “Wallace was extraordinarily prescient about this,” he said, “complaining as early as 1863 that his fellow Victorians were hypocrites in their insistence, as creationists, that each species was the handiwork of God, yet all the while failing to lift a finger to conserve them.”

“In an essay, Wallace wrote that: “Future ages will certainly look back upon us as a people so immersed in the pursuit of wealth as to be blind to higher considerations. They will charge us with having culpably allowed the destruction of some of those records of Creation which we had it in our power to preserve; and while professing to regard every living thing as the direct handiwork and best evidence of a Creator, yet, with a strange inconsistency, seeing many of them perish irrecoverably from the face of the earth, uncared for and unknown.

“It was from Wallacea, Jonathan Kennedy, an ornithologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of Sheffield, told New York Times, that Wallace sent his famous letter to Darwin, laying out what he had reasoned about evolution and persuading Darwin to publish his own ideas for the first time. “So, the discovery and description of biological diversity can be considered a significant driving force behind the development of one of the greatest ever scientific theories,” Dr. Kennedy said.

Endangered Animals in Indonesia

Indonesia has 68 critically endangered species, 69 endangered species, and 517 vulnerable species. Many of Indonesia's most well-known species are also endangered. According to a 2006 report issued by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), threatened species included 146 types of mammals, 121 species of birds, 28 types of reptiles, 33 species of amphibians, 91 species of fish, three types of mollusks, 28 species of other invertebrates, and 383 species of plants.

Brazil, China and Indonesia have the most species at risk. Some sources claim Indonesia has more threatened species of the animals than anywhere else in the world — around 600. According to the Rainforest Action Network, Indonesia has more species of mammal than any other nation — 515 — but unfortunately, it also leads the world in the number of threatened mammals at 135 species, which is nearly a third of all of its native mammals. The eight hottest biological "hot spots" are: 1) the Caribbean; 2) Western Ghats and Sri Lanka; 3) Sunderland (Sumatra, Malaysia, Borneo and Java); 4) the Philippines; 5) Brazil's Atlantic Coast; 6) Coastal forest of Kenya and Tanzania; 7) Madagascar; and 8) Indo-Myanmar.

Nations with the most threatened species include: 1) Indonesia (128 mammal and 104 bird species); 2) Brazil (71 mammal and 103 bird species); 3) China (75 mammal and 90 bird species); 4) India (75 mammal and 73 bird species); 5) The Philippines (49 mammal and 86 bird species); 6) Peru (46 mammal and 64 bird species); 7) Mexico (64 mammal species); 8) Columbia (64 bird species); 9) Australia (58 mammal species); 10) Papua New Guinea (57 mammal species); 11) Ecuador (53 bird species); 12) Madagascar (46 mammal species); 13) the U.S. (50 bird species); 14) Vietnam (47 bird species). [Source: Data from the 2000s]

Rare Species in Indonesia

Among the rare species in Indonesia are the single-horned Javan rhinoceroses, orangutans, Komodo dragons, Sumatran tigers, pig-tailed langurs, Javan gibbon,s Malayan tapirs, Sumatran rhinoceroses, mainland serows, Rothschild's starlings, lowland anoa, mountain anoa, Siamese crocodiles, false gavials, river terrapins, and four species of sea turtle (green sea, hawksbill, olive ridley, and leatherback). The Kalimantan mango, Buhler's rat, and the Javanese lapwing have become extinct.

Rare and notable birds include the green jungle fowl, an ancestor of the domestic chicken; the blue streaked lory, a red and plank parrot; the rhinoceros hornbill; the Great Argus pheasant; and Bali myna, a popular pet caged bird. The Rothchild’s myah is a beautiful, endangered birds with pure white feathers and a strip of blue around the eyes. They are popular pets. In Japan, these birds are being bred in a captive breeding program with the goal of releasing into the forests of Bali. The Amboina king parrot is a large, colorful bird found on Ambon in the Moluccas.

The crested black macaque, a species of monkey, is found only in the rain forests of northeastern Sulawesi. Weighing about 10 kilograms (22 pounds),these short tailed monkeys communicate with a wide variety of facial expressions. A smile, for example, can be an expression of friendliness or submission depending on the situation. Pressured by loss of habitant and illegal hunting, the population of these animals declined by 75 percent to around 5,000 individuals on a 15 year period.

Animals in Sumatran Rain Forest Parks

According to UNESCO: The biodiversity of the rain forest parks in Sumatra “is exceptional in terms of both species numbers and uniqueness. There are an estimated 10,000 species of plants, including 17 endemic genera. Animal diversity in TRHS is also impressive, with 201 mammal species and some 580 species of birds, of which 465 are resident and 21 are endemics. Of the mammal species, 22 are endemic to the Sundaland hotspot and 15 are confined to the Indonesian region, including the endemic Sumatran orangutan. Key mammal species also include the Sumatran tiger, rhino, elephant and Malayan sun-bear. [Source: UNESCO]

“Sumatra has a high level of endemism, which is well represented in the nominated sites. It is evidence of the land bridge/barrier between the Sumatran biota and that of mainland Asia due to changes in sea level. Some of the animal distributions may also be evidence of the effect of the Mount Toba tuff eruptions 75,000 years ago. The Sumatran orangutan for example, is not found south of Lake Toba nor the Asian tapir north of it. The altitudinal range and connections between the diverse habitats in these areas must have facilitated the ongoing ecological and biological evolution. Key mammals of the parks are the Sumatran tiger, Sumatran rhino, orangutan, Sumatran elephant; also Malayan sun-bear and the endemics Sumatran grizzled langur, Hoogerwerf's rat. Rare birds noted in the site's nomination are Sumatran ground cuckoo, Rueck's blue flycatcher, Storm's stork and white-winged duck.

The species listed below represent a small sample of iconic and/or International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Listed animals and plants found in the property.

White-winged Wood Duck (Asarcornis scutulata)

Sumatran Ground-cuckoo (Carpococcyx viridis)

Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Storm's Stork (Ciconia stormi)

Sunda Otter Civet

Rueck's Blue-flycatcher (Cyornis ruckii)

Sumatran Rhinoceros

Sumatran Elephant

Smooth-coated otters

Southern Pig-tailed Macaque (Macaca nemestrin)

All three parks that comprise the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra are areas of very diverse habitat and exceptional biodiversity. Collectively, the three sites include more than 50 percent of the total plant diversity of Sumatra. At least 92 local endemic species have been identified in Gunung Leuser National Park. The property contains populations of both the world’s largest flower (Rafflesia arnoldi) and the tallest flower (Amorphophallustitanium). The relict lowland forests in the sites are very important for conservation of the plant and animal biodiversity of the rapidly disappearing lowland forests of Southeast Asia. Similarly, the montane forests, although less threatened, are very important for conservation of the distinctive montane vegetation of the property.

10 New Bird Species and Subspecies Found Off Sulawesi

In January 2020, in a study published in Science, scientists announced that haf found 10 new species and subspecies of songbirds off the coast of Sulawesi, with distinct songs and genetics from known birds. Karen Weintraub wrote in the New York Times: “One day in 2009, Frank Rheindt was wandering up a forested mountainside on an Indonesian island when the skies opened up. He had spent months planning this trip, days finding a charter boat that would carry him to this remote place, and hours plodding uphill, but the local tour guides insisted that the rain would make the search impossible. Reluctantly, Dr. Rheindt agreed to head to lower ground. But on the way down, even with the deluge, he was startled by the sight of a thrush sitting on a log. Dr. Rheindt, an ornithologist, knew that a thrush shouldn’t have been on that island, and that the species normally would seek shelter from the rain. A little farther along, he heard the distinctive call of a grasshopper warbler, an endangered bird that’s normally hard to spot. “I could tell from the sound that it was a grasshopper warbler, but different than I was used to,” he said. “That’s when I knew I was going to come up again.” [Source: Karen Weintraub, New York Times, January 9, 2020]

“On his second ascent a few days later, Dr. Rheindt, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore, saw little besides the devastation from a forest fire a few years earlier. But on his third mile-high climb, he found what he had struggled so long and hard to track: birds that no scientist had ever before recorded. Dr. Rheindt and colleagues published a study in Science on their findings from that six-week trip and a follow-up in 2013. They identified five new songbird species and five subspecies — a number considered remarkable from one place and time. Their proposed names for the birds include: Peleng Fantail, Togian Jungle-Flycatcher and Sula Mountain Leaftoiler.

“The region off the coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia, that was explored by the team has a rich history, one that Dr. Rheindt anticipated would yield exciting finds. The Indonesian islands of Taliabu, Peleng and Batudaka are in a region named Wallacea, after Alfred Russel Wallace, the 19th-century naturalist who developed a theory of evolution alongside Charles Darwin’s. Wallace and other explorers spent decades cataloging the birds of Wallacea, but they had somehow missed these birds — probably, Dr. Rheindt said, because his own search focused on the highest elevations. “Dr. Rheindt said it had taken him more than six years since his last expedition to publish his results, because of the need to confirm each bird’s distinctiveness — including genetics, appearance and vocalizations. It also took time to collaborate with colleagues in Indonesia and get appropriate permits and buy-in from Indonesian authorities. Two of the new species are named in honor of Indonesian officials.

“Taliabu and Peleng are surrounded by deep water, suggesting that they had been separated from other land masses for hundreds of thousands of years, enough time for new species to evolve. Since Darwin wrote about his explorations of the Galápagos Islands off Ecuador, scientists have known that isolated island populations often evolve into new species. “Most of the 10 new birds discovered in Wallacea are related to species found elsewhere, but they sing somewhat different songs and have distinct genetics. The islands are both inhabited — largely at lower elevations than where Dr. Rheindt traveled, but he used logging trails to reach some sites. Human habitation and exploitation of natural resources threaten the islands’ habitats, he said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025