OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA

About 10,000 years ago, the last ice age began to recede and seas rose, eventually creating from the Sunda Shelf the archipelago of Indonesia we know today. Indonesians today are, like Malaysians and Filipinos, of Malay origin and are the descendants of migrants that arrived around 4000 B.C. Before them some Indonesian islands were inhabited by pygmy-like Negritos that resemble people still found today in the jungles of Luzon, the Philippines and in peninsular Malaysia. The ones in Indonesia were exterminated some scientists say by tribes resembling Australian Aboriginals.

Malays speak Austronesian languages. Austronesian-speaking peoples originated in southern China but developed as a distinct group in Taiwan. Beginning 4,000–5,000 years ago, they launched a major seafaring expansion, island-hopping through the Philippines into the central Indonesian archipelago. From there they spread west into Borneo, Java, and Sumatra—where they encountered Austroasiatic migrants—and east into regions inhabited by earlier Australoid populations.Over time, Austronesian groups became dominant across Indonesia.

Early inhabitants had an agricultural economy based on cereals, and introduced pottery and stone tools during the period 2500 to 500 B.C. During the period between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500, as the peoples of the archipelago increasingly interacted with South and East Asia, metals and probably domesticated farm animals were introduced. [Source: Library of Congress]

People in Indonesia may have been among the first to develop agriculture. There is some evidence of wild yam and taro cultivation dating back to 15,000 and 10,000 B.C. in Indonesia.

The Dongson Culture from Vietnam and China introduced bronze casting, irrigated rice farming, ritual buffalo sacrifice, ikat weaving methods and megaliths around 1000 B.C. Some of these practices remain in areas including the Batak areas of Sumatra, Toraja in Sulawesi, and several islands in Nusa Tenggara. The artefacts from this period are Nekara bronze drums discovered throughout Indonesian archipelago, and also ceremonial bronze axe. Trade with India by 200 B.C. introduced Hinduism and Buddhism, shaping early kingdoms in Sumatra, Java, and Borneo.

Life of Early Indonesians

Beginning around the 7th century B.C. organized societies began to take shape in different locations in Indonesia. These people practiced irrigated rice farming, used copper and bronze, domesticated pigs and other animals, practiced seafaring and established villages around rice fields. These early Indonesians were animists who believed in an afterlife not so different from their life on earth and were buried with tools and weapons they could use in the next world. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Early Indonesians practiced animism, honoring nature spirits and the spirits of deceased ancestors whose life force was believed to aid the living. This tradition endures among many Indigenous groups—such as the Nias, Batak, Dayak, Toraja, and Papuans—and is reflected in harvest ceremonies, rituals invoking nature deities, and elaborate funerary practices. The concept of powerful ancestral or natural spirits, known as hyang in Java and Bali, persists in Balinese Hinduism today.

Prehistoric livelihoods ranged from forest hunter-gatherers using stone tools to agricultural communities engaged in grain cultivation, animal domestication, weaving, and pottery. Favorable conditions and the mastery of wet-rice cultivation as early as the 8th century B.C. enabled the rise of villages, towns, and small early kingdoms by the A.D. 1st century Wet-rice agriculture, especially in Java’s fertile volcanic soils, required highly organized social systems compared to simpler dry-rice farming.

According to Archaeology magazine: Early excavations of a site called Harimau (Tiger) Cave on the island of Sumatra are providing rare insight into the lives of the country’s first farmers 3,000 years ago. The finds in the limestone shelter include the earliest known rock art in Sumatra (as well as fragments of ochre that may have been used to paint it), remnants of tool and jewelry manufacture, and 66 sets of human remains. Researchers are still trying to determine whether the caves served as habitation sites, workshops, cemeteries — or all of the above. [Source: Samir S. Patel. Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

One early cultural tradition, the Buni culture of northern West Java and Banten (c. 400 B.C.– A.D. 100), is known for its distinctive pottery and is considered a precursor to the Tarumanagara kingdom, one of Indonesia’s earliest Hindu states and the beginning of Java’s recorded history.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVA MAN AND HOMO ERECTUS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

HOMO FLORESIENSIS: HOBBITS OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ORIGINS AND ANCESTORS OF HOMO FLORESIENSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

EAST TIMOR — HOME OF THE WORLD’S FIRST DEEP SEA FISHERMEN factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST PEOPLE OF INDONESIA: NEGRITOS, PROTO-MALAYS, MALAYS AND AUSTRONESIAN SPEAKERS factsanddetails.com

Toaleans — 7,200-Year-Old Sulawesi Culture

Toalean people were ancient, enigmatic hunter-gatherers who lived on Indonesia's Sulawesi island, known for unique tools like 'Maros points' and microliths, existing before Austronesian farmers arrived around 3,500 years ago. They hunted warty pigs, gathered shellfish, and left behind enigmatic artifacts, with recent DNA from a burial (Leang Panninge) revealing connections to early modern humans in Wallacea and traces of Denisovan DNA, suggesting complex migration patterns in the region.

In 2021, researchers announced that they had have uncovered the 7,200-year-old remains of a teenage girl in Sulawesi presumably from the Toalean culture. DNA extracted from the “Leang Panninge” remains—named for the cave where she was found—shows that the 17–18-year-old belonged to the prehistoric Toalean culture, an elusive hunter-gatherer group that mysteriously vanished about 1,500 years ago. The findings, published in Nature, offer new insight into ancient human migrations across the Wallacea region, a chain of Indonesian islands used as “stepping stones” by early modern humans traveling between Eurasia and Oceania more than 50,000 years ago. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, August 26, 2021]

Archaeologist Dr. Adam Brumm of Griffith University described the Toaleans as “enigmatic,” noting that their culture “seems to come out of nowhere … apparently having no or limited contact with other early foraging cultures elsewhere in the island.” They occupied only a small area of Sulawesi’s southwestern peninsula and left behind distinctive stone tools and finely made arrowheads known as Maros points, but very few fossils—and until now, no usable DNA.

The painstaking recovery of genetic material from the girl’s bones paid off: researchers found that she shared ancestry with modern Papuans and Indigenous Australians whose ancestors reached Wallacea around 50,000 years ago. This challenges the earlier assumption that Asian populations entered the region only about 3,500 years ago.

Yet the DNA also contained genetic signatures that do not match any known ancient or modern population. “We cannot say who this population was,” said Dr. Cosimo Posth of the University of Tübingen. “But it formed a unique profile in this ‘genetic fossil’ never seen before in any present-day or ancient individual.” The girl also carried traces of Denisovan DNA, suggesting these archaic humans ranged far more widely than previously believed.

What ultimately happened to the Toaleans remains a mystery. Their culture appears to have been displaced by later human migrations and mixing in the region. “It seems to be replaced by later human movements and admixture,” Posth said, “leaving us with the question: what happened to the bearers of the Toalean culture?”

7,000-Year-Old Tolean Shark-Tooth Knives

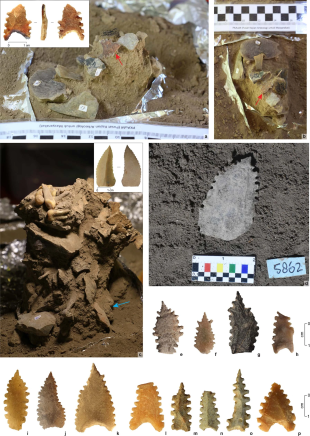

Excavations at a Tolean people site on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi have uncovered two rare and lethal artefacts dating back roughly 7,000 years—tiger shark teeth fashioned into blades. Reported in Antiquity, these discoveries represent some of the earliest evidence anywhere in the world for the use of shark teeth in composite weapons, tools constructed from several components. Previously, the oldest known shark-tooth blades were less than 5,000 years old. [Source: Adam Brumm, Michelle Langley, Adhi Oktaviana, Basran Burhan, Griffith University, and Akin Duli, Universitas Hasanuddin. The Conversation, October 2023]

Both teeth were found during a joint Indonesian–Australian excavation and come from sites associated with the Toalean culture—a mysterious foraging society that lived in southwestern Sulawesi from about 8,000 years ago until an uncertain point in the recent past. Using scientific analysis, experimental replication, and comparisons with recent Indigenous technologies, our international research team concluded that these modified teeth had once been mounted on handles. Their design and wear patterns suggest they served as weapons or ritual tools, rather than everyday knives.

Each tooth came from a two-metre tiger shark (Galeocerda cuvier) and is similar in size. Both were intentionally perforated. One tooth from Leang Panninge has two holes drilled through the root. The other, from Leang Bulu’ Sipong 1, is broken but originally appears to have had two holes as well. Microscopic analysis revealed that both teeth had been securely bound to handles using plant fibres and a resin-like adhesive made from mineral, plant, and animal materials—a technique still seen in shark-tooth weapons used across the Pacific.

Although residue might suggest mundane use, ethnographic parallels, archaeological context, and experimental tests point strongly toward ritual or combat functions. The Sulawesi teeth stand apart from shark-tooth weapons found in the Pacific region and other places. . Their deliberate shaping, perforation, and the microscopic traces of binding and adhesive indicate that they were mounted as blades—and almost certainly used in conflict or ritual cutting. Whether they sliced human or animal flesh, these shark-tooth blades from Sulawesi may represent the oldest known weapons of their kind in the Asia–Pacific, pushing back the origins of this distinctive technology thousands of years earlier than previously recognised.

Megaliths in Indonesia

Stone monuments called megaliths can be found across the Indonesian archipelago and are still being built today. Menhirs, dolmens, stone tables, ancestral stone statues, and step pyramid structure called Punden Berundak have been discovered in various sites in Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and the Lesser Sunda Islands. Cipari megalith site in West Java has stone terraces and a sarcophagus.The Punden step pyramid is believed to be the predecessor and basic design of later Hindu-Buddhist temples structures in Java such as 8th century Borobudur and 15th-century Candi Sukuh. Living megalith cultures can be found on Nias, an isolated island off the western coast of North Sumatra, the Batak people in the interior of North Sumatra, on Sumba island in East Nusa Tenggara and also Toraja people from the interior of South Sulawesi. These megalith cultures remained preserved, isolated and undisturbed well into the late 19th century. [Source: Wikipedia]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: As islanders’ resources began to grow, they began to build megalithic structures to mark the graves of honored ancestors. Archaeologist Dominik Bonatz of the Free University of Berlin has conducted research on Sumatra and is building a database of the island’s estimated 1,500 megalithic sites. He has relied in large part on traditional stories to reconstruct the history of sites built from the early seventeenth century until the present. He possesses a uniquely helpful resource: the records of nineteenth-century missionaries who collected information from local people about the sites. Today, he says, people can still recall traditions associated with certain megaliths going back more than 15 generations, noting that their recollections match the stories collected by the missionaries. “They have a remarkably accurate memory of these sites,” says Bonatz. “Monuments constructed three hundred years ago still have very real meaning to them.”[Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

On the island of Sumba, archaeologist Ron Adams of Willamette Cultural Resources has studied how people conduct a ceremony known as tarik batu, or “pulling the rock.” This ritual involves acquiring stones from local quarries and dragging them to cemeteries where they are used to construct mortuary megaliths. He says islanders who have the means save for their entire lives to pay for monumental tombs built during what anthropologists call feasts of merit. During these multiday festivals, as many as 1,000 people from related clans gather to haul stones weighing several tons. They also enjoy music, dancing, and feasts, all underwritten by the family or even a single individual who wishes to honor a relative or themselves. “Many of these tombs are built during the occupant’s lifetime,” says Adams. “It’s the fulfillment of a life’s dream for many.” He has observed feasts that involved slaughtering 100 pigs and 10 water buffalo—a considerable expense—during the construction of some the largest tombs on Sumba. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

Archaeologist Tara Steimer-Herbet of the University of Geneva, who has excavated megalithic sites in the Near East for many years, has also observed tarik batu on Sumba. She says experiencing the songs and dancing and seeing expensive textiles draped over stones during the ritual led her to think differently about the prehistoric structures she has studied throughout her career. “They aren’t just these mute monuments,” says Steimer-Herbet. “They were erected during what must have been massive parties that were meaningful not just for the people who participated in them, but also for their descendants.” Just as they do on Sumatra and Sumba today, prehistoric megalithic monuments in the Near East and across the ancient world likely reminded people of the ancestors they honored and the rituals surrounding their construction.

Megaliths were built by ancient cultures across the world. Scholars will never know the precise reasons why Neolithic people in southern Britain first came together to build Stonehenge around 3000 B.C, or what motivated the inhabitants of Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, to carve their majestic moai. Today, many people living on the islands of the Indonesian archipelago still carry out rituals surrounding the creation of modern megaliths. They have many insights to offer archaeologists seeking to understand why the people of the past invested so much time and energy in building similar monuments. Archaeologist Dominik Bonatz of the Free University of Berlin has a long-running project on the island of Sumatra dedicated to excavating and recording megaliths that people living there still remember and revere.

Gunung Padang

Gunung Padang (50 kilometers, 31 miles southwest of Cianjur) is a megalithic site in the highlands of Karyamukti, West Java. Constructed over the course of several generations beginning around 2,000 years ago, it is situated at an elevation of 885 meters (2,904 feet) above sea level and covers a hill — an extinct volcano— and is comprised of a series of five terraces bordered by retaining walls of stone that are accessed from the valley below by 370 successive andesite steps rising about 95 meters (312 feet). Cut into a promontory, the archaeological site is covered with massive hexagonal stone columns of volcanic origin. The Sundanese people consider the site sacred and believe it was the result of King Siliwangi's attempt to build a palace in one night. [Source: Wikipedia]

Gunung Padang consists of a series of five artificial terraces—one rectangular and four trapezoidal—that occur, in succession, at progressively higher elevations. These terraces also diminish in size as elevation increases, with the first being the lowest and largest, and the fifth being the highest and smallest. The terraces are aligned along a central longitudinal NW–SE axis. They are artificial platforms created by lowering elevated areas and filling in depressions until a flat surface was achieved. The perimeters of the terraces feature retaining walls constructed from volcanic polygonal columns, stacked horizontally and erected vertically as posts. Access to the complex is provided by a central stairway with 370 steps, an inclination of 45 degrees, and a length of 110 meters

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Each terrace is covered with rectangular megalithic structures composed of hundreds of prismatic andesite blocks that geologists call columnar joints. These are igneous stones that owe their shape to repeated heating and cooling when the volcano was active millions of years in the past. Scholars believe that, centuries ago, the ancestors of today’s local Sundanese people conducted sacred rituals on these terraces. The lowest and largest terrace, Terrace 1, features a five-foot-long andesite block that makes a loud, deep sound when struck. The Sundanese call it a batu kecapi, or “stone lute.” From Terrace 5, the highest and smallest of the terraces, one can take in a spectacular vista that includes two nearby volcanic mountains. Gunung Padang draws local Muslims who read the Koran aloud amid the stones and Hindus from the island of Bali who climb the mountain’s steps to conduct rituals related to the rising of the full moon. Followers of the Indonesian martial art pencak silat practice their discipline high on the mountain. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

After Gunung Padang was recorded in the early twentieth century, the site was ignored by archaeologists for more than 50 years. Then, in 1979, three farmers from the nearby village of Karyamukti rediscovered the site and brought it to the attention of local authorities. Excavations carried out by the National Archaeology Research Institute in the 1980s exposed the monument’s basic layout. Archaeologist Lutfi Yondri of the University of Padjadjaran and his team began excavating the site in the late 1990s.

See Separate Article: WEST JAVA: ANCIENT HISTORY, GUNUNG PADANG, SUNDANESE CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Megaliths of Bada Valley

Lore Lindu National Park in Central Sulawesi houses ancient megalith relics such as ancestral stone statues. Mostly located in the Bada, Besoa and Napu valleys. The Bada Valley, or Napu Valley, is famous for its prehistoric relics from an ancient megalithic culture. Dozens of finely carved megaliths dating between 3000 B.C. and A.D. 1000 are scattered across the valley and are mysterious, yet magnificent testament to the skill and genius of a civilization that we know absolutely nothing about. Located in the District of Poso in Central Sulawesi, the megaliths are set in scenic landscape of rice paddies and green plains, streaked with small streams, and surrounded by soft rolling hills which give way to dense forests and rocky mountains. The Lairiang River flows through the entire valley and is crossed by three hanging bridges. The river is channeled into irrigation ditches that nourish terraced rice fields.

Compared to the monuments on Easter Islands, the Megaliths of Bada Valley are impressive but are difficult to access, as they are situated deep among hdden valleys in mountainous Central Sulawesi. Some are found in the middle of valleys, some in streams, open fields or rice paddies. The statues of Bada Valley are carved in human or animal forms such as an owl, monkey or buffalo; all with the similar, and rather abstract style: oval in shape with large, round faces. The largest statue stands 4.5 meters tall and is 1.3 meters thick. Sources indicate that they show remarkable resemblance to the stone statues on Cheju Island in Korea, and the Olmec statues in Mexico.

Nobody really knows how old the megaliths are, who made them or why they’re there. The most common response from the area’s inhabitants when asked about their origin is that “they’ve always been there.” The locals have various explanations for the meaning of these statues. Some believe they were used in ancestral worship or may have had something to do with human sacrifice. Others believe that these statues ward off evil spirits. One legend tells that they are criminals which were turned to stone, and there is even a superstition that the statues can disappear or move from place to place. Some have even been reported found in slightly different locations. Another curious aspect about these statues is that they are made from a type of stone not found anywhere near the area where they have been placed as is the case with Stonehenge.

See Separate Article: CENTRAL SULAWESI factsanddetails.com

Rock Art in Indonesia

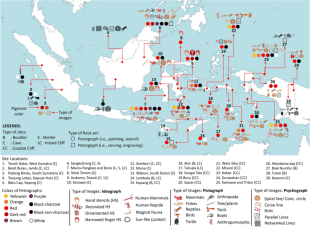

Indonesia boasts globally significant rock art sites, particularly in Sulawesi (Maros-Pangkep) and Borneo (Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat), featuring some of the world's oldest figurative art, including hunting scenes and hand stencils, dating back over 45,000 years, with major discoveries extending to Sumatra and Nusa Tenggara, showcasing diverse styles from animal depictions to geometric patterns.

Rock art from West Sumatra features more recent, geometric, and anthropomorphic motifs, often in white pigment, contrasting with the older eastern sites. Alor and the Kisar Islands in Nusa Tenggara contain unique sites showing processions and cultural exchange, often with volcanic or limestone settings.

Rock art sites in Indonesia provide clues on early human migration, belief systems, maritime culture, and artistic innovation, challenging Eurocentric views on the origin of art. Subjects include Hand stencils, animal figures (pigs, banteng), human-like figures, boats, geometric designs, and narrative hunting scenes. Red (ochre), purple, and black pigments are used. Dates range from tens of thousands of years ago (e.g., Sulawesi, Borneo) to more recent periods, highlighting complex cultural traditions.

Indonesian research agencies (like BRIN) collaborate with international bodies (like Griffith University) to study and digitally preserve these sites. Efforts are underway to nominate sites like the Maros-Pangkep caves for UNESCO World Heritage status.

Prehistoric Stone Sculpture from New Guinea

In 2017, archaeologists in New Guinea announced they had discovered several ornately decorated stone statues at a cemetery that may be more than 3,000 years old. Archaeology magazine reported: Erlin Novita of the Papua Archaeological Center led a team that found the statues at Mount Srobu on the island’s north coast, in Indonesia’s Papua province. Here burials were hewn into limestone bedrock and covered with shell mounds by people of the megalithic cultures who likely made the statues. Most megalithic human depictions are simple, but the three-foot-tall statues unearthed by Novita’s team are complex. The bodies are posed in a crouching position, similar to statues known from Polynesia. Novita believes the statues represented important ancestors and were objects of worship. She notes that they are visually similar to the smoked mummies of Papuan chiefs that are traditionally preserved in a crouched position and that continue to be venerated in some parts of New Guinea to this day. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The earliest known works of Oceanic sculpture are a series of ancient stone figures unearthed in various locations on the island of New Guinea, primarily in the mountainous highlands of the interior. To date, no examples have been excavated from a secure archaeological context. Although organic material trapped within a crack in one example has recently been dated to 1500 B.C., firm dating and chronology for the figures are otherwise lacking. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jennifer Wagelie, Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2001]

The stone sculptures fall into three basic categories: mortars, pestles, and freestanding figures. The tops of many pestles are adorned with images of human heads, birds, or bird's heads. The mortars display similar anthropomorphic and avian imagery as well as geometric motifs. Freestanding figures include depictions of humans, birds, and phalluses, as well as long-nosed animals that some scholars identify as echidnas (spiny mammals resembling hedgehogs). While the original significance and function of these stone images remain unknown, they possibly represent totemic species or ancestors and were likely used in ritual contexts. When found by contemporary New Guinea peoples, these early stone sculptures are often thought to be of supernatural origin and are reused in a variety of religious contexts, from fertility rituals to hunting magic and sorcery.

Indonesian ‘Eves’ Colonized Madagascar 1,200 Years Ago

In 2012, scientists announced that several dozen Indonesian women founded the colonization of Madagascar 1,200 years ago. AFP reported: “Anthropologists are fascinated by Madagascar, for the island remained aloof from mankind’s conquest of the planet for thousands of years. It then became settled by mainland Africans but also by Indonesians, whose home is 8,000 kilometers away. [Source: AFP, March 21, 2012 =]

“A team led by molecular biologist Murray Cox of New Zealand’s Massey University delved into DNA for clues to explain the migration riddle. They looked for markers handed down in chromosomes through the maternal line, in DNA samples offered by 266 people from three ethnic Malagasy groups. Twenty-two percent of the samples had a local variant of the “Polynesian motif,” a tiny genetic characteristic that is found among Polynesians, but rarely so in western Indonesia. In one Malagasy ethnic group, one in two of the samples had this marker. If the samples are right, about 30 Indonesian women founded the Malagasy population “with a much smaller, but just as important, biological contribution from Africa,” it says. =

“The study focussed only on mitrochondrial DNA, which is transmitted only through the mother, so it does not exclude the possibility that Indonesian men also arrived with the first women. Computer simulations suggest the settlement began around 830 AD, around the time when Indonesian trading networks expanded under the Srivijaya Empire of Sumatra. The study appears in the British journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.=

“The investigation points to other contributions from Southeast Asia. Linguistically, Madascagar’s inhabitants speak dialects of a language that traces its origins to Indonesia. Most of the lexicon comes from Ma’anyan, a language spoken along the Barito River valley of southeastern Borneo — a remote, inland region — with a smattering of words from Javanese, Malay or Sanskrit. Other evidence of early Indonesian settlement comes in the discovery of outrigger boats, iron tools, musical instruments such as the xylophone and a “tropical food kit,” the cultivation of rice, bananas, yams and taro brought in from across the ocean. Madagascar was settled approximately 1,200 years ago, primarily by a small cohort of Indonesian women, and this Indonesian contribution — of language, culture and genes — continues to dominate the nation of Madagascar even today,” the paper says. =

“How the 30 women got across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar is a big question. One theory is that they came in trading ships, although no evidence has ever been found that women boarded long-distance merchant vessels in Indonesia. Another idea is that Madagascar was settled as a formal trading colony, or perhaps as an ad-hoc center for refugees who had lost land and power during the expansion of the Srivijayan Empire. Yet a third — and more intrepid — hypothesis is that the women were on a boat that made an accidental transoceanic voyage. That notion is supported by seafaring simulations using ocean currents and monsoon weather patterns, says Cox’s team. Indeed, in World War II, wreckage from ships bombed near Sumatra and Java later washed up in Madagascar as well as, in one case, a survivor in a lifeboat.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025