TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO

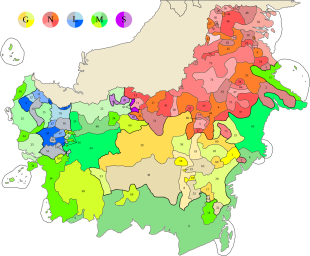

By one count there are 300 ethnic groups in Borneo. Indigenous groups like the Dayaks, Penan, Iban speak their own languages, many of which are grouped in the Kayanic family which in the Western Malayo-Polynesian (Austronesian) language group. Many follow customary laws known as “adat” and taboos known a “pli “. They have their own religions, although many are now Muslim or Christian,

Adat is supervised and administered by headmen and elders. Sometimes it is codified like modern laws. But often each village has their own adat. Many Bornean societies rank members into aristocrats, commoners or slaves.

Malays make up 40 percent of the population of West Kalimantan. They are distinguished from Dayaks in that they are Muslims and the Dayaks are not. There are also many Madurese (See Java)

Book: “Into the Heart of Borneo” by Redmond O'Hanlon, an excellent adventure book by a quixotic Oxford professor looking a rare rhinoceros. Also worth checking out is “Headhunters of Borneo” by 19th century German explorer Carl Boch. Joseph Conrad described the town of Samarinda in “Almayer's Folly” (1895).

RELATED ARTICLES:

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJUA SEA PEOPLE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJUA LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILIES, VILLAGES, CULTURE, LIFE AT SEA factsanddetails.com

SAMA-BAJAU GROUPS OF THE PHILIPPINES, BORNEO AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

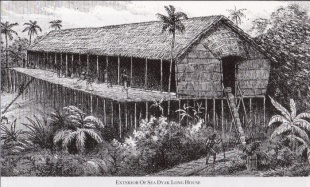

Longhouses

Many Bornean people have traditionally lived in longhouses that hold up to a 150 people and are like village under one roof. In the center of house is a common room off which the rooms of the house radiate, sort of like side streets off of a main square. The rooms are connected by a common veranda or porch. The kitchen is divided from the main room by a wall and in the corner an area, where women slept. Men often slept outside. There were traditionally no windows. In the old days there were no possessions except for some large pots used for storing and fermenting wine.

The residents of the longhouse sleep on straw mat floors in one room and eat around an open cooking fire in another. The center of the traditional social life is the long porch, where old people gather in the evening to chat, weave rattan baskets, repair fishing nets and relax while their children watch television powered by Honda generators. One longhouse dweller said, “The longhouse is like a multimedia super corridor for us. We know instantly if someone in the family has a problem because information travels fast in a longhouse.”

Longhouses were originally built in part for defense. they are built on stilts for protection from animals, insects and raiding tribes. Dogs, chicken and children run loose although prized gamecocks are tethered by the their owner’s door. Modern longhouses have metal roofs and shuddered windows. Some have electricity; some don’t. Waste from people and animals in the long houses drops through slats in the floor.

See Separate Article: IBAN factsanddetails.com

Sago

The pulp of the sago palm is the staple for many Borneo groups. To many groups the sago palm is known as the tree of life. To harvest sago, saga limbs are cut down, the trunks are split open lengthwise and the soft pith is pounded. Indonesians and Malaysians on many islands eat sago as their primary food. It is ground into a powder. Boiling water is poured on it and it is pounded into a kind paste. Many eat it with fish sauce.

Sago is raised commercially in swampy areas. When the palms are harvested theyare felled and trunks are dragged to villages. The bark is stripped off in segments into which the stem has been cut. The pith inside is rasped into rough sawdust. The sawdust is washed and mixed with water and placed on a mat and trampled by foot. The water with suspended flour is poured through the mat, leaving woody material behind. The surplus water is drained away and the paste is allowed dry.

Among the Penan food has traditionally been shared: Their staple food has traditionally been sago, which grows extensively in the swampy lowlands and sporadically in the hills, and fruit from rain forest trees. Sago pulp is trampled under foot while water is added and strained through a rattan mat and then dried into a powder.

Dayak Hunting

Monkeys and flying squirrels were traditionally dispatched by Dayak hunters with blowguns with poison darts and wild pigs, deer, pythons and bear were hunted with spears. Eggs laboriously collected from wild jungle fowl were usually reserved for children. Other traditional Dayak weapons include axes, machetes and knives. Fishing techniques range from using fishing rods to using their unique-style seine. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

When hunting deer and or wild boar, Dayak tribesmen generally do not actively pursue animals but rather like to hunt in clearings drawing the animals to them. They have a unique method for attracting deer: they imitate the sound of a young deer. Since does (female deer) always protect their young, if the call is done well enough the female deer will approach as soon as they hear the sound for help. In hunting, Dayak have traditionally used lances or blowpipes. A blowpipe is very is long and can be fitted with a kind of bayonet so it also functions as a lance. Blowpipe darts used for hunting are smeared with a poisonous concoction that paralyzes or even kill prey. Blowguns are especially good for hunting monkeys and other animals in the trees.

See Hunting Under DAYAK LIFE factsanddetails.com

Punan Batu — Borneo’s Last Hunter-Gatherers

The Punan Batu live along the Sajau River near Tanjung Selor in Bulungan Regency, North Kalimantan. Known for their deep forest life, unique song language (Latala), and distinct genetics, they inhabit caves and rely on hunting wild pigs, gathering tubers, and forest products for survival. Facing threats from deforestation and land encroachment by palm oil plantations, their traditional territory and way of life are increasingly vulnerable, despite efforts for recognition and protection, including the 2024 Kalpataru award.

According to the New York Times the Punan peoples of Borneo were once rumored by their neighbors in the nineteenth century to have tails, a reflection of how elusive and poorly understood they appeared at the time. Unlike Indigenous farming communities who lived in permanent longhouses, the Punan traditionally moved through the northern rainforests in small family groups. They survived by hunting bearded pigs, harvesting starchy forest plants, and gathering forest products that they traded with settled populations. [Source: Brendan Borrell, New York Times, Sept. 19, 2023]

The Punan were not only misunderstood but also mistreated. Over many decades, the Indonesian government removed them from large areas of their ancestral lands and encouraged, and at times forced, them to settle in permanent villages. By the nineteen nineties, many anthropologists believed that the Punan hunter gatherer way of life had effectively disappeared. A census conducted in eastern Borneo in 2002 focused exclusively on settled villages, based on the assumption that nomadic groups no longer existed in meaningful numbers.

The origins of the Punan remain uncertain. Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, small hunter gatherer populations share physical traits such as dark skin, short stature, and tightly curled hair, and are believed to descend from the earliest modern humans who left Africa more than sixty thousand years ago. On Borneo, however, early European explorers encountered Punan who closely resembled neighboring Dayak farmers. Many Punan groups, including the nomadic Punan Batu, also maintained long standing trade relationships with settled communities, further complicating simple distinctions between foragers and farmers in the island’s interior.

Punan Batu Genetics and Song Language

In 2018, Stephen Lansing, an anthropologist at the Santa Fe Institute, and Pradiptajati Kusuma, a geneticist at the Mochtar Riady Institute for Nanotechnology in Tangerang, met up with a small clan of about thirty Punan families living in limestone caves and rarely, if ever, leaving the forest. The claim was met with skepticism by many experts. With funding from the National Science Foundation, the researchers collected data, with a focus on safeguarding their health and well being. [Source: Brendan Borrell, New York Times, Sept. 19, 2023]

After the initial visit, Lansing returned with photographs of a man wearing a loincloth made from bark fiber and with recordings of a song language that appeared unlike any previously documented. His first scholarly description of the group, who refer to themselves as the Cave Punan or Punan Batu, was published in the journal Evolutionary Human Sciences. Media coverage in Indonesia drew the attention of local authorities and prompted the government to recognize the Punan Batu as regular users of their forest, an essential step toward securing legal rights to manage it under national law.

Despite this recognition, some scholars remain doubtful that the group could have remained so isolated for such a long period. Critics have compared the announcement to the case of the Tasaday in the Philippines, a group presented in 1971 as a lost tribe whose isolation was later shown to have been greatly exaggerated. Bernard Sellato, a specialist on Punan societies affiliated with the French National Center for Scientific Research, has been among the most outspoken critics. He has described the Punan Batu and similar groups as inauthentic and has argued, based on historical and ethnographic sources, that their ancestors were enslaved people brought from New Guinea and eastern Indonesia several centuries ago.

New genetic research, however, appears to contradict this interpretation. A study focusing on the genetic material of the Punan Batu, recently accepted by a scientific journal, shows extremely limited genetic diversity, suggesting that the group has been isolated for more than twenty generations. These findings are inconsistent with the idea that the Punan Batu descend from relatively recent populations brought to Borneo through slavery.

The results may also help resolve long standing debates about when the Punan arrived in Borneo and how they came to practice a hunter gatherer lifestyle. Beyond their academic significance, the findings strengthen arguments that the Punan Batu should have a role in managing and protecting their forest, which is increasingly threatened by palm oil plantations and commercial logging. According to Lansing, their most urgent wish is to halt the destruction of their forest environment.

Native Courts and Customary Law in Borneo

In 2020, AFP reported: A Pakistani man has been ordered by a native court in the Malaysian part of Borneo to pay a fine consisting of eight buffaloes and eight gongs after being found guilty of insulting Indigenous groups, according to an official statement released on Wednesday. The ruling highlights the continued authority of customary law in parts of the island, which is home to a wide diversity of Indigenous communities. [Source: AFP, July 22, 2020]

In Malaysian Borneo, particularly in Sabah, special native courts exist to adjudicate cases involving Indigenous laws and customs. Amir Ali Khan Nawatay, a fifty year old businessman and permanent resident of Malaysia, appeared before a native court in Sabah after making derogatory remarks about Indigenous groups in May and June. He pleaded guilty to the charges and was subsequently fined under customary law.

Baintin Adun, the district chief of Kota Marudu, who presided over the case, explained that recordings of the remarks had circulated widely on social media, provoking strong public anger. He stated that the court intended the ruling to serve as a deterrent, emphasizing the importance of respecting ethnic differences and avoiding racial references during disputes. While the exact content of the remarks was not disclosed, officials confirmed that they were considered deeply offensive by local communities.

Amir was given one month to pay the customary fine. Failure to do so could result in a monetary penalty of four thousand Malaysian ringgit, a prison sentence of up to sixteen months, or both. In Sabah’s Indigenous societies, buffaloes and gongs are traditionally regarded as items of high value and are commonly used in the settlement of disputes, compensation for offenses, and even as components of marriage dowries.

Ethnic relations remain a sensitive issue in Malaysia’s multi ethnic society, and Sabah is among the country’s most diverse states, with numerous Indigenous peoples and languages. The case underscores both the cultural significance of customary law in the region and the broader importance of maintaining social harmony in a culturally plural society.

Borneo Tribal Jewelry and Clothes

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contain a skirt from Borneo made in the early to mid-20th century from cotton, beads and shell. It s 49.5 centimeters (19.5 inches) in length.

A beaded vest worn by the Bidayuh people of Sarawak is a rare old piece and very intricate. According to Leonard Yiu, a collector of tribal jewelry, the Bidayuh costumes of today are different as the beads are very big. There are also a few selendang (scarf) textiles, pua (Sarawak tribal tapestry) and other fabrics that were hand-woven. Some are local and some, from Indonesia. Some of the selendang textiles are woven with gold threads, which Yiu says denotes that royalty wore them. [Source: Brigitte Rozario, The Star (Malaysia), September 17, 2006

According to Yiu, the age of the selendang can be gauged by the general wear and tear of the item. In addition, the workmanship of older pieces is better and the design usually more intricate. “If it’s machine-made the feel is different. Being hand-woven you can see the lines on the selendang are not straight. The machine-made ones of today have very straight lines. Somehow, it loses its appeal without that human touch,” says Yiu.

Among the silver items made by Borneo people are hairpins, sireh (betel nut) boxes and even modesty plates (worn by children, who didn’t usually wear any clothing) from around the region. Yiu says, “Some of the items I bought had been passed down from grandparents or ancestors. When I asked (the people whom I bought these items from) what a particular symbol meant, they had no idea. Most native peoples don’t have their own written language so everything has been passed down orally. Because of this, a lot has been lost. “For instance, the motifs on the costumes and jewellery have meaning but it was lost when the symbolism was not passed down to the current generation,” Yiu said.

Plaited Arts and Baskets from Borneo’s Rainforest

Kalimantan is home to one of the world’s oldest rain forests and some of its most diverse plant life. It is no surprise then that the tribal people that live there have a rich basketry traditions closely tied to the forest environment. To help prevent these traditions from disappearing, the Lontar Foundation, together with the Total E&P Indonésie Foundation and Bentara Budaya, organized an exhibition of Kalimantan basketry at Bentara Budaya Jakarta in March and April 2023. [Source: Niken Prathivi, The Jakarta Post, March 31 2013]

Basketry is one of humanity’s oldest crafts. The term “basketry” covers a wide range of plaited items, including containers, mats, hats, fish traps, and carriers. The island’s basketry traditions developed within a broader Southeast Asian context shaped by ancient migrations and cultural exchange. Influences from India, China, and later Islamic and Western cultures, especially from the 16th century onward, blended with local practices. As a result, similarities can be seen between Bornean plaited arts and objects from southern China, Indochina, and the Dong Son culture of northern Vietnam.

According to John McGlynn, chairman of the Lontar Foundation, Borneo possesses the richest and most varied plaited traditions in the world, yet they remain little known. At the exhibition’s opening, the foundation also launched Plaited Arts from the Borneo Rainforest, a book drawing on studies by 20 experts. McGlynn warned that without sustained support from private, corporate, and government sectors, these traditions risk being replaced by cheap imported plastic goods.

Basketry materials are drawn directly from the tropical forest and include rattan, bamboo, palm, pandanus, sedge, reeds, grasses, and ferns. Choices depend on availability, durability, resistance to water and pests, ease of processing, and dye absorption. Techniques are simple but labor intensive, relying on hand-assembled plant fibers without frames or looms. Plaited works are generally grouped into plaiting, twining, and coiling, each with many variations.

Form and size follow function. Wide, flat hats offer better protection from sun and rain, while small waist baskets are used for sowing rice and large burden baskets carry harvests from field to village. Decorative motifs vary by region and ethnic group and continue to evolve through innovation and reinterpretation.

Dayak basketry motifs are often named after elements of the natural world, such as flowers, birds, fruits, or notable individuals. Some patterns, like the dove’s eye motif, are found across the island, while others carry multiple meanings. A triangular design may represent a bamboo shoot, an areca palm bud, a blade point, or a durian thorn, depending on the group. An eight-branched star can signify a flower, a tiger footprint, or a mangosteen fruit.

The exhibition displayed hundreds of Dayak basketry pieces, from palm hats and woven mats to functional baskets, baby carriers, and food covers. According to Central Kalimantan Governor Agustin Teras Narang, who also heads the National Dayak Tribe Council, these motifs symbolize gods, human relationships, and the environment, themes also seen in the Dayak tree of life designs. Many basketry objects carry stories of mythical heroes, spirits, and gods, giving them deep social and ritual meaning.

Problems Faced by Borneo Tribes

Over the past decade, interior Borneo has undergone rapid transformation driven by commercial logging, agricultural expansion, plantations, and tourism projects. Since 1990, scientific studies indicate that logging has affected nearly eighty percent of the land surface of Malaysian Borneo. As forests disappear, so too do traditional livelihoods that depend upon them. Combined pressures from new logging roads, climate change, and the aspirations of younger generations for education and urban employment have placed Kelabit society in a state of tension between continuity and change. [Source: Karen Coates, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2014]

Key issues faced by indigenous tribes in endangered according to SKEPHIs-Indonesia Third World Forum (TWF) research:

1) Development and resettlement of indigenous people;

2) Lack of infrastructure for the indigenous people;

3) Damage to habitat and the environment of the traditional community;

4) Relocation and land grabbing from the traditional community;

5) Absence of education or access to information for the traditional community;

6) Issues of interdependence, poverty and economics;

7) Victims of exploitation and the criminality of outsiders;

8) Issues of human settlement due to a narrowing area of responsibility;

9) Issues of discrimination and women’s emancipation among the indigenous people;

10)The presence of threats to the traditional community’s biological diversity;

11)Absence of political and legal acknowledgment of the existence of the indigenous community;

12)Threats to the indigenous community’s cultural elements, such as its values, language, arts, handicrafts and other traditional cultural elements;

13) Violation of the community’s intellectual property rights in the form of artwork duplications, stealing of genes and unpaid royalties;

14)Health issues that have arisen as a consequence of changes in the ecosystem and a lack of facilities; and

15)The presence of the transmigration programs. [Source: Sinapan Samydorai, Human Rights Solidarity, August 14, 2001]

See Separate Article: PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026