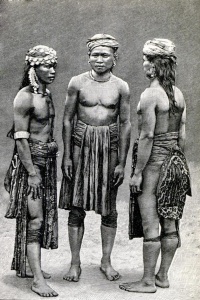

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS

Dayak refers to any non-Muslim living on Borneo. There are something like 200 distinct Dayak tribes. From an outsider’s perspective, most of the scattered ethnolinguistic groups inhabiting the interior of the vast island of Borneo have been referred to as Dayak. The word is a collective term used by outsiders since 1836 to indicate the indigenous peoples of Kalimantan in Indonesia and Sarawak and Sabah in Malaysia. [Source: Library of Congress]

Dayaks are a collection ethic groups that have traditionally lived in the forests in both the Malaysian and Indonesian sides of Borneo. They are sometimes distinguished from the Malay population in that for the most part they are not Muslims. Instead they are animists or Christians but some are Muslims. Sometimes Dayaks are distinguished from groups like the the Penan who have traditionally been nomadic while most Dayaks have been relatively settled .

Despite centuries of cultural exchange through trade and repeated population movements across Borneo, Dayak groups have retained distinct traditions and identities from one another. Their cultural affiliations are often stronger with communities acessible by sea than with those separated by mountain ranges. Identity is commonly rooted in ancestral river valleys. For example, a Ngaju Dayak from Central Kalimantan may identify as an oloh (“person of”) Kahayan, Katingan, or Serayun, depending on their place of origin. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Even a broad classification of Dayak peoples reveals considerable diversity. These include the nomadic Punan of the remote interior forests; the Murut-Kadazan of Sabah and neighboring parts of Indonesia, whose languages are most closely related to those of the Philippines; the Lun Dayeh and Lun Bawang, who are culturally linked to the Kelabit of Sarawak; the Kayan and Kenyah of eastern Kalimantan; and the Land Dayaks and Sea Dayaks, or Iban, of western Kalimantan, who speak Malay dialects but do not share Islamized Malay culture. Also included are the large Barito River groups of central Kalimantan, such as the Ma’anyan, Ngaju, Ot Danum, Benuaq, and Tunjung. ^^

RELATED ARTICLES:

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Kalimantan Dayaks

Among the people labeled as Dayak in Indonesia are the Ngaju, Danum, Maanyan, and Lawangan. The Kalimantan Dayaks live in Kalimantan. They are also known as Biadju, Bidayuh, Dajak and Daya. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

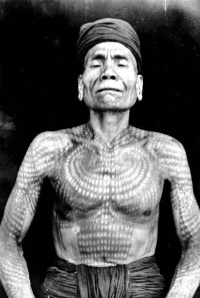

Ngaju Dayaks are the largest central Kalimantan group. They have traditionally lived along the larger rivers and resided in two or three family houses rather than long houses. They rely more on fishing than hunting Sometimes villages are politically united under the same chiefs. Tattooing and teeth filing have traditionally been practiced. Slavery was reportedly practiced until recently. In some cases slaves were killed at the funerals of chiefs. They regard the Danum as their cultural ancestors.

Danum Dayaks live on the headwaters of rivers and speak a dialects of the same language, which is similar to the one spoken by the Ngaju. They make dugout canoes and gather and trade rubber, lumber and forest products. The Danum raise dogs, pigs and chicken; cattle are raised for celebrations. Iron forging is done with bamboo double-piston bellows. They own, buy and sell land. There are approximately 30,000 of them.

Maanyan Dayaks live in the drainage system of the Patai Rive and share a common language but live in separate sub groups, each with its own set of “adat”. They do not live in longhouses. Each nuclear family has its own dwelling and fields. Shaman preside over funerals, treat illnesses through spirit possession, entertain with dances, and keep track of the past with myths, histories and genealogies. There are about 35,000 Maanyan Dayaks.

Land Dayaks are a heterogenous group that inhabits western Kalimantan and southern Sarawak. They have traditionally lived in villages with 600 people living in one or a few longhouses. They used to live along fortified hilltops but now largely live along streams. Their villages have a head house, which serves as a men’s house and council house. In the old days hunted heads were stored below it. The Land Dayaks also have a long tradition of trading with the Chinese.

Ngaju Dayaks

The Ngaju Dayaks of Central Kalimantan are the largest Dayak group in terms of population and the most influential politically and culturally in Indonesia. The name "Ngaju" signifies upriver (as opposed to ngawa, downriver). The Ngaju distinguish themselves from the Ot Danum, related but more conservative peoples living even further upriver (Ot itself means "upriver" and Danum means "water" or "river"). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Ngaju Dayaks originated from a homeland along the Kahayan River in present-day Central Kalimantan province and spread as far west as the Seruyan Valley. entral Kalimantan province consists of several north-south running river valleys from the Schwaner and Muller Mountains to the Java Sea. Swamps extend deep into the interior from the coast, where they give way to dense jungle. Ngaju Dayaks settled at the mouth of the Kapuas River, but as one approaches the sea, they become increasingly mixed with non-Dayak peoples. The upper reaches of the rivers are largely inhabited by the related Ot Danum Dayak.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project, the Ngaju Dayak population in the early 2020s was 1,205,000.According to the 2000 census in Indonesia, when they were first listed as a separate ethnic group, the Ngaju constituted 18 percent of Central Kalimantan's population, or 334,000 out of 1.86 million. They were outnumbered by the Banjarese who made up 24 percent of the population and equaled the 18 percent of the Javanese. . A 2003 estimate put the number of Ngaju speakers at 800,000. ^^

See Separate Article: NGAJU DAYAKS factsanddetails.com

Kayan and Kenyah

The Kayan. Kenyah and Kajang refers to a complex group that has traditionally lived on rivers in Sarawak. Also known as the Kenya and Bahau, they have traditionally lived in longhouses and used to be headhunters. The Kenyah and Kayan are the main groups. The Kajang is comprised of a number of small groups that have gradually assimilating into one or the other of the two larger groups. Numerous subgroups exist within each category. The Kenyah and Kayan languages are closely related and belong to the Austronesian language family. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Kenyah live in the drainage area of the Aop Kayan river. The Kayan live on mid sections of the major central Borneo rivers: the Kayan, Mahakam, Kapaus, Rajang and Baram. The Kajan live on the mid portions of the Rajang River. Rice, corn, yams, pumpkins, cucumbers and tobacco are the primary crops. The Kayan are skilled metal workers, canoe builders and wood carvers. Their knives and swords are sought after by other groups. The Kenyah grow rice in fields controlled by women and fish with poison and hunt with blowguns. Chickens are raised for sacrifice.

Both the Kenyah and Kayan trace their origins to the headwaters of the Kayan River. The Kenyah appear to have lived in central Borneo for a long period, whereas the Kayan, a more mobile and expansionist group, arrived later from the south and east. During their expansion, the Kayan enslaved and assimilated Murut and other neighboring groups. In the early twentieth century, the Brooke administration brought an end to the headhunting and warfare that had characterized relations among these peoples.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project Kenyah-speaking people numbered 73,000 in the early 2020s and included 2,000 Kelinyau Kenyah in Indonesia, 17,000 Kelinyau Kenyah in Malaysia, 13,000 Mahakam Kenyah in Indonesia, 900 Upper Baram Kenyah in Indonesia and 29,000 Upper Baram Kenyah in Malaysia. The Wahau Kenyah in Malaysia numbered 1,300, of which 72 percent are Christian, with two to five percent being Evangelicals; the Kayan River Kenyah in Indonesia number 11,000, of which 72 percent are Christian, with two to five percent being Evangelicals. [Source: Joshua Project]

The total population of Kayan is around 200,000. According to Joshua Project 1) the Murik Kayan in Malaysia number 3,400 of which 2 to 5 percent are Christian,with most being followers of traditional animist religions; 2) The Baram Kayan number 13,000 of which 96 percent are Christian, with 50 to 100 percent being Protestant Evangelicals; 3) The Busang Kayan in Indonesia number 5,700 of which 10 to 50 percent are Christian, with with most being followers of traditional animist religions; and 5) The Wahau Kayan in Indonesia number 900 of which 2 to 5 percent are Christian, with with most being followers of traditional animist religions.

Kayan and Kenyah Life and Society

Kayan, Kenyah and Kajang societies are highly stratified. Aristocrats have a lot of power and wealth has traditionally been measured in gongs, beads, mats and caves where edible bird’s nests are gathered. Commoners are mostly farmers and craftsmen. Slaves are the descendants of prisoners of war. Each longhouse has a headman. In the old days the social calendar revolved around the head feats, which required a new head. This feasts are now rare for obvious reasons. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Kayan also have reputation for fierceness. They were formidable headhunters in the past and enslaved many Murut. A central institution in the traditional life of the Kenyah and Kayan was the mamat, or head feast, a practice that has become rare due to Christian influence. The mamat required the acquisition of a new head and served several ritual purposes, including purification, marking the end of mourning for a deceased relative, or ritually completing the construction of a new longhouse.

Marriages generally take place within one’s class and longhouse community. Grooms traditionally often did a bride service in lieu of a bride price. Marriages between first cousins are forbidden except among the aristocracy who can marry anyone they like. If the spouse is from a lower rank their children of an intermediate class.

Swidden rice cultivation forms the basis of subsistence, supplemented by corn, yams, pumpkins, cucumbers, and tobacco. In some Kenyah groups, women exercise control over rice cultivation. Fishing, often more important than hunting in the diet, is commonly carried out using tuba root poison. Hunting is practiced mainly with dogs and blowguns, with wild pigs as the principal quarry. Domestic animals include goats, dogs, pigs, and chickens, the latter two being especially important for ritual sacrifice. The Kenyah and Kayan are renowned for their skills in woodworking, metalworking, and canoe building, and their knives and swords are widely traded throughout central Borneo. Rubber has become the most important cash crop for the Kenyah. Among the Kayan, individuals who clear primary forest land acquire undisputed ownership of it.

Kayan and Kenyah Villages and Longhouses

The Kayan are famous for their longhouses which can reach 300 meters in length and house 500 people. Notable for their durability as well as scale, they are usually well built with ironwood planks and raised on pilings originally for defensive purposes. Each family owns the structural components of its section of the longhouse. Unmarried older boys and male slaves have traditionally slept on the veranda while unmarried girls, women and female slaves slept with their families. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Each longhouse has traditionally been led by an aristocratic headman, and in villages with multiple longhouses one headman also serves as village leader. Political authority generally does not extend beyond the village level, although in the past large war parties sometimes united men from several villages. Kayan headmen additionally receive free agricultural labor from villagers.

Among the Kenyah, a village typically consists of a single longhouse, whereas Kayan villages may comprise multiple longhouses and range in population from several dozen to more than one thousand inhabitants. Each village claims a section of river as its territory. Because of soil depletion, villages periodically relocate along the river and return to former sites after twelve to fifteen years.

Kayan and Kenyah Culture

Kenyah storehouses are distinguished by the curly-cue carvings and paintings on the roof and the walls. Their territory in the rain forest is marked by grave markers that double as border demarcations. The Kenyah entomb their dead in structures called liang, which often mirror the design of their homes, but have more elaborately carved, upward-curving wooden extensions along the rooftops and eaves. Some life essentials accompany the deceased in these structures, including salt, a sword, tobacco, and eating utensils. Brass gongs and pottery decorate the outside, denoting wealth. The Kenyah construct liang downstream from their villages to prevent the dead from returning to the realm of the living. Some groups erect tombs that resemble clan homes.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

The Datun Julud — Hornbill Dance — is a traditional dance of Sarawak's Kenyah women. Created by a Kenyah prince called Nyik Selong to symbolise happiness and gratitude, it was once performed during communal celebrations that greeted warriors returning from headhunting raids or during the annual celebrations that marked the end of each rice harvest season. Performed by a solo woman dancer to the sounds of the sape, beautiful fans made out of hornbill feathers are used to represent the wings of the sacred bird.

Kayan and Kenyah shields (klau or kliau), hudoq masks, and mandau sword exemplify the close integration of warfare, ritual, and art in Kenyah and Kayan culture during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Warfare and head-taking were central to male status and social prestige, and martial equipment functioned not only as practical tools but also as powerful symbolic objects. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007; Metropolitan Museum of Art ]

Large wooden shields were carved from single planks and reinforced with rattan bands, providing defense against swords, spears, darts, and, in some accounts, even bullets through supernatural protection. Their painted designs, typically featuring fearsome supernatural faces, were believed to ward off malevolent forces, protect the warrior, and intimidate enemies. Many shields were adorned with human hair taken from slain foes, marking the owner as a successful warrior, and were also displayed and carried in ceremonial war dances.

Hudoq masks, among the most dramatic ritual sculptures of Borneo, were used primarily in rice-fertility ceremonies. Worn by young men in leaf costumes, the masks represented powerful spirits invoked to protect rice crops, ensure fertility, and safeguard human souls. Their terrifying yet attractive appearance was believed to repel harmful spirits while attracting benevolent ones. Beyond agriculture, hudoq masks were employed in healing rites, during epidemics, and when confronting unknown visitors, highlighting their broad protective and spiritual functions.

The mandau sword, finely crafted from steel with elaborately decorated hilts and sheaths, was both a weapon and a status symbol. Renowned throughout central Borneo, it formed part of the warrior’s ceremonial and combat equipment. Together, these objects demonstrate how Kenyah and Kayan material culture embodied spiritual beliefs, social hierarchy, and the central importance of warfare and ritual in community life.

Modang

Modang is a generic term used to describe a culturally related group of Dayaks that live around the Mahakam River and its tributaries in the Kutai regency of East Kalimantan in Indonesia. There are five Modang groups— 1) Long Belah (Medéang), 2) Long Glit (Long Gelat), 3) Long Way (Medang), 4) Menggaè (Segai) and 5) Wehèa (Wahau) According to the Christian group Joshua Project there are 29,000 Modanag (early 2020s). An estimate from the 1980s counted around 5,000 of them. [Source: Antonio J. Guerreiro, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

From 1810 to 1840, the Modang ruled over a large swath of Borneo. They challenged the Malay sultanate for control of the area and practiced headhunting on a large scale and continued do so until the 1920s. Today they are regarded as more conservative and resistant to change than other Dayak groups. They retain many of the old taboos and some villages still have men’s houses and chief’s houses. Their chiefs also have more power and carry greater respect than other Dayak groups.

The Modang are primarily subsistence farmers and rice is their main crop.. They also fish, gather forest products and hunt with dogs and spears. In the dry season men migrate to find jobs or pan for gold. The Modang are regarded as skilled craftsmen. They produce elaborate carved wood houses, pots, doors, boards and staircases filled with spirit, animal and ornamental designs. They also have masked dances and epics. Within the wider Dayak the Modang display distinctive features. These include a characteristic village organization marked by the presence of a men’s house and the chief’s “great house” In general, the Modang appear more conservative than neighboring groups, retaining cultural practices abandoned elsewhere, such as the numerous taboos (pliʼ) observed during the rice agricultural cycle.

Modang Language belongs to the Kayanic family within the Western Malayo-Polynesian branch of Austronesian languages, yet it constitutes a distinct language group. The five Modang isolects remain mutually intelligible, despite long-term processes of lexical innovation and occasional phonological change. These subgroups have been separated for more than two centuries.

Modang Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project two to five percent of Modang are Christians. Most follow their traditional animist religion. The Modang religious system envisions a tripartite universe consisting of the upper world or sky, the earth, and the underworld. The upperworld, divided into seven layers, and a lower world, regarded as the dwelling place of deities. The supreme deities are a pair of goddesses named Doh Ton Tenye and Dea Long Meleum. In addition to them there is a host of other deities, spirits and ghosts.Thunder gods occupy a central role, enforcing taboos and customary law by punishing human transgressions. [Source: Antonio J. Guerreiro, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Modang calender is full of ritual and ceremonies. Life events such as births, namings, marriages and funerals are also marked, residing over these are ritual specialists who also act as spirit mediums. For head hunting rituals pieces of old skull are used. Taboos are given great importance. Broken taboos or the mockery of animals are punished by supernatural sanctions from the thunder gods.

The Modang believe in two souls: one for the living and one for the dead. The souls of people who died a violent death, it is believed, go up to another place and they are buried separately.

Chiefs were formerly buried in large mausoleums, and carved statues of high-status ancestors were erected during major rituals as symbols of prestige and as expressions of Modang aesthetic and religious values.

Modang Society

There are five hereditary ranks in Modang society: 1) chiefs; 2) aristocrats; 3) commoners; and 4) and 5) two classes of slaves, which in the old days were enemies who were captured rather than beheaded. Some of these groups are viewed in terms of two categories: 1) those who speak; and 2) the populace. . Status is determined by descent, with adopted children taking the rank of their parents, and marriage ideally occurring within ranks, although mixed-rank unions were common. [Source: Antonio J. Guerreiro, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Each Modang village is regarded as a separate, independent political unit and is headed by a chief who makes decision in conjunction with a council of elders and aristocrats in a great house. In the men’s house is a dormitory for unmarried young men and meeting areas for aristocrats. Authority is communicated through a village crier, and men’s houses serve as political, ritual, and social centers, reinforcing a division between influential speakers and the general populace.

Kinship is bilateral. Along male and female lines, and encompases wide networks of relatives and contacts, but without formal obligations beyond mutual support. Residence patterns group closely related households together, reinforced by taboos that discourage nonrelatives from living between kin. Descent lines are linked to ranked ancestors, with chiefly lineages maintaining long genealogies to support political and ritual claims.

The household is the central social and economic unit, functioning as a production, consumption, and ritual group. Households typically consist of nuclear or stem families, average about five members, and own their own rice barns. While households are theoretically enduring, some die out over generations, and gradual partitioning of extended domestic units occurs over time. Marriage involves graded bride-price payments based on rank, and involves residence within the wife’s community, and is regulated by prohibitions on close-kin unions; polygyny is reported mainly among chiefs.

Modang Life, Villages and Culture

Modang villages have 200 to 600 residents and are usually set up on high river banks near the confluence of rivers with longhouses with three to six apartments or individual dwelling linked by plankways and oriented so the ridge beam follows the flow pattern of the river. Rows of longhouses and individual houses line a central street and correspond to two named village moieties, one closer to the river and one farther inland. Each village controls a shared territory for farming. In the past, settlements periodically relocated in response to omens or misfortune, but this practice has ceased. Low population density has allowed swidden agriculture to function effectively. [Source: Antonio J. Guerreiro, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Modang houses have an ironwood frame with two levels: a low platform and living quarters connected by a notched log. This form is used for all major buildings, including longhouses and the chief’s great house. Neighboring households are closely related by kinship and are not separated by nonrelatives. A taboo forbids non-relatives from occupying longhouses occupied by relatives.

Primarily subsistence agriculturists, the Modang combine fishing and hunting with gathering of forest products. Fishing is a daily activity whereas hunting, practiced with dogs and spears, is less important. Hill rice (plaè), their major crop, is cultivated on swiddens located on flat river banks, usually with long fallow periods (12-20 years). Rattan gardens are also planted. Modang occasionally pan for gold during the dry season. Today men commonly find temporary jobs throughout the year with nearby timber companies.

Modang culture includes highly developed crafts such as mat making, basketry, beadwork, metalworking, and wood carving, often featuring spirit and animal motifs. Artistic expression also extends to painted murals, collective and masked dances performed on ritual occasions, and rich vocal traditions of chants and epics.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026