PENAN

The Penan are an ethnic group of nomadic forest hunters that live mostly in Sarawak but also live in smaller numbers in Kalimantan and Brunei. They have traditionally lived a nomadic life in the forest while Dayaks were more settled. The Penan are also known as Punan, Pennan, Poenan, Poonan, Pounan. Punan is often used as a general term for Bornean forest dwellers. In two dialects in East Kalimantan “punan” means "to gather," "to collect," and "to assemble things or goods."

The Penan (pronounced peh-NAHN) recognize two main groups: the East Penan and the West Penan. These two groups are culturally distinct and geographically separated by the Baram River. According to the Christian group Joshua Project there are 12,000 Penan in the early 2020s. Most live in Sarawak, though some live in Kalimantan and Brunei. There are believed to be only around 70 Penan groups, with only about 300 living a completely nomadic life. The Penan have traditionally lived alongside other groups rather than in their own distinct territory. Some of the last groups of nomads are found in Gunung Mulu National Park in Sarawak.

The Western Penan—comprising the Penan Silat of the Baram District, as well as the Penan Geng, Apau, and Bunut—are concentrated in the Belaga District and the Silat River basin in the Kapit and Bintulu divisions. The Eastern Penan, also known as Penan Selungo after the Selungo River, live mainly in the Baram River basin within the Miri and Limbang divisions. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

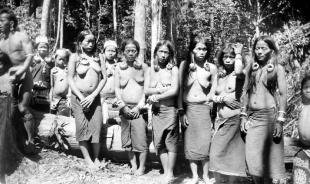

The Penan are similar to but more solidly built than most Dayaks, a reflection perhaps of strength built up from a hard forest life. They share some features with other Sarawak peoples but tend to have lighter skin, attributed to their preference for forest shade and avoidance of direct sunlight. Compared with neighboring settled Dayak groups, the Penan have generally experienced less influence from outside societies.

Penan Language has several dialects. Although they do not have a written language, the Penan have an interesting method of relaying messages. They use various items, such as shoots, leaves, stones, sticks, and feathers, to leave messages along jungle paths. These items are used to show directions, give instructions to wait or follow, and indicate danger, hunger, disease, death, or food. The Penan poke sticks into the ground and attach leaves or feathers to them to show direction, time, and the number of families passing through. In the 1970s, missionaries first attempted to write down the Penan language. One of their accomplishments was writing and compiling a Penan Bible. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Book: “Voice n the Rainforest” by Bruno Manser. The anthropologist D.B. Ellis wrote a paper about the Penans in 1972.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

History of the Penan

Little is known about the history of the Penan before the early 19th century, when they occupied settlements on the Hiahm Suai and Buk rivers. They are believed to have arrived at that location by traveling through the Lio Matu area from Pejungan. They have been encouraged for long time towards settlement by colonial and present-day governments. The Penan have been included as Orang Ulu by Malaysian government census. Twenty-seven of the inland tribal groups of Sarawak are collectively called Orang Ulu or upriver people. The Penan have are traditionally been nomadic people living in small family groups constantly moving from place to place within the rainforest. Today most Penan people have settled in longhouse communities where their children have the chance to go to school.

The Penan are most likely descendants of farmers who migrated from Taiwan between 5,000 and 2,500 B.C.. At some point afterthey arrived in Borneo, they left farming behind and started living off the land, relying on the abundant game, fruits, nuts, and sago palm. Unlike other Orang Ulu groups, the Penan never went to war with other groups or took heads as trophies. They had no need for land to farm, and it wouldn't have made sense for them to carry around a bunch of skulls as they wandered from place to place. They continued living this nomadic lifestyle until after World War II, when missionaries began penetrating one of the world's least-known regions. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Smithsonian magazine, March 2016]

In the 1950s, the anthropologist Tom Harrison of the Sarawak Museum proposed that the Penan were not a separate ethnic group but are descendants of villagers who became nomads to escape headhunting raids by the Kayan and Iban in the 19th century. Studies have shown that languages spoke by the Penan vary somewhat from group to group but are related to those spoken by non-Penan villagers in the area where they live.

Traditionally, the Penan did not attend school. However, due to government persuasion, more and more Penan are now attending government schools. In 1987, approximately 250 Penan children attended primary school, while about 50 others attended schools farther away. By the beginning of the 21st century, fewer than 12 Penan youth had attained a tertiary education. Most of these were the children of the settled Penan. While the children of the settled Penan attend government schools, the children of the nomadic Penan receive lessons from their parents, grandparents, uncles, and aunts. The elders are seen as having knowledge and wisdom to impart to younger generations. The Penan also believe that knowledge is taught through experience. Therefore, from a young age, children are taught survival skills in the forest. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Decline of Penan Nomadism

Roughly one-quarter of the Penan population is fully settled, about half is semi-settled and lives part of the year in small, scattered villages, and around 2,000 people remain fully nomadic. Settled Penan live in longhouses or individual houses in villages, much like other indigenous groups in Sarawak. Nomadic Penan live in small bands that depend heavily on the forest for their subsistence. These bands typically consist of two to ten families, or about 20 to 40 people, who move together within clearly recognized territories. Other groups are not permitted to enter these territories unless invited, for example to share seasonal fruit. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

In 1970, there were 13,000 nomadic Penan living in the forests of Sarawak. By the early 1990s only 350 remained. The remainder were either settled or semi-settled in up river villages, where they farmed rice, bananas and tapioca. Many still hunted and gathered food in the forest but only a few hundred practice nomadism.

The Malaysian government argues they are doing the Penan a favor by bringing them in line with the modern world. One leading official in Sarawak said, “How can we have an equal society when you allow a small group of people to behave like animals in the jungle.” The Penan’s rain forest home remained relatively undisturbed until the 1970s when logging roads penetrated the Sarawak interior. They lost food sources, ancestral graves and rattan palms which they used to make mats and baskets.

Penan Religion

Christianity has been spread since World War II. With the support of the Borneo Evangelical Mission, some Penan have converted to Christianity. The rest remain animists, believing in a supreme god called Bungan and in the soul of nature itself. They also believe that forests are filled with powerful spirits that must not be disturbed. If they are deliberately disturbed, the spirits get angry and inflict disease on people. Therefore, the Penan leave these spirits in peace, appease them with sacrifices, and threaten them with magic words. [Source: P. Bala, A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Penan also strongly believe in taboos and omens. Dreams, animals such as deer and snakes, and bird sounds and flights are omens that indicate the correct course of action. For instance, a Penan will turn back if he or she hears a kingfisher's call at the beginning of a journey. They will only continue the journey if they hear the call of the crested rainbird. They believe that disobeying the taboos and omens will result in hardships, illness, or death. ^^

Funerals and Afterlife: The Penan believe they have two souls: one that is physical and emotional and the other, a "dream wandering state" that is experienced during sleep or a trance when they see through they eyes of animals or spirits. They also believe certain plants can give their dogs special hunting skills. At death, the body is wrapped in woven mats and buried near the camp or beneath the hearth of the deceased’s shelter. To ease their grief, the group then moves and builds new shelters elsewhere in the forest. The Penan believe in an afterlife, envisioning a rainforest above the sky where human souls live free from illness, hardship, and pain, hunting and harvesting sago in abundance.

Penan Gods and Spirits

The Penan believe in a creator god named Peselong and rely on shaman to cure illnesses by removing illness-causing spirits. They have sacred mountains like Batu Lawi, a pair of male and female peaks in the middle of the Bornean jungle. Rivers have mythological names and connections to ancestors. The Western Penan believed their society originated in the upper Lua river region. [Source: P. Bala, A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Penan believe that natural phenomena, spirits and magic are all interconnected. Thunder is a manifestation of “balei ja’au”, powerful magic of the forest. Trees bloom in response to the sound of peacock songs. The calls of some birds bring good fortune while the calls of others brings bad luck. Their universe is divided into the land of shade, the land of abundance and the land that has been destroyed.

“Because we are now Christian, we only believe in Lord Jesus,” one young nomadic Penan man told Smithsonian magazine. “I know there are other spirits, but I do not belong to them anymore.” He goes on, though. Every living thing has a spirit, and humans can harness it. “The hornbill spirit can make people walk very fast. Normally what takes two, three days to walk, they do it in one. The leopard spirit is even more powerful.” [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Smithsonian magazine, March 2016]

Penan Creation Myth

In the beginning, according to the Penan creation myth, there was only sky and water and a sun and moon that didn't move. After eons and eons rocks fell to earth and later came rain which pulverized the rock into mud. Worms emerged from the mud are bore holes in the rock which allowed mother earth to break through the ground. [Source: "Vanishing Tribes" by Alain Cheneviére, Doubleday & Co, Garden City, New York, 1987, *]

Later still the sun dropped a female tree trunk and the moon deposited a male plant which gave birth to a pair of legless humans with roots instead of legs. Their offspring also didn't have legs but they made a deal with the animals who supplied the human hybrids with legs in return for a promise that they wouldn't hunt the animals. The first people honored the pledge but their descendent didn't and the animals demanded their legs and when the humans refused a bitter fight ensued. Wit the help of the forest a new deal was struck: the people would only hunt what they need for food and the animals would sacrifice a certain number of victims if the hunters blessed their souls. In memory of their original ancestors the Penan bury their dead in the trunk of a tree. *

The first man and women stood in the forest while two large trees blew around in a windstorm. They didn't know about sex. As the watched the trees in the storm a branch from a tree entered a hole in another tree, giving the first man and woman an idea. Their first child was the result. *

After reading this Giffard Sercombe e-mailed me in 2021: Having spent time with Eastern Penan every year for the last 20 years, I can assure you they have no creation myths.

Penan Ornamentation and Tattoos

Like many Bornean peoples, the Penan traditionally practiced ear elongation and wore earrings. Penan women traditionally shaved the hair on their upper forehead and temples and plucked their eyelashes and eyebrows to enlarge their forehead which is seen as a sign of beauty. They generally don't stretch their earlobes with hoops although some Dayak tribes do. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York ♢]

Penan men traditionally cut their hair "bowl style" and sported long ponytails. Their ears are pierced with two holes: one at the top of the ear for wart hog tusks or wads of tobacco and a lower one for metal hoops. Their earlobes are stretched from infancy with gradually increased weights added as they get older which sometimes pull their earlobes down as far as their shoulders. Shaman and elders sometimes wear loincloths headdresses made from rattan and hornbill feathers and have tattoos and distended pierced earlobes. ♢

"For the major experiences of a Penan's life," Blair writes, "whether an inner dream or an outer experience, are commemorated with a ritual tattoo. Most of the men wore tattoos on their chests, throats and arms, and the women on their wrists and legs...[Tatoo masters] always work as a couple—a man (for whom it is taboo to draw blood, except in anger) to trace the symbol, and a woman laboriously to open up the wound and hammer in the dye. Out tattooists took less than half an hour to paint the design on our chests, but their partners took closer to six ours to make it permanent. I thought it was finished after three...but there was only a patterned pink wound, an eighth of an inch deep, into which she went on meticulously to beat the carbonized wood dye. This was achieved with a strip of bamboo tipped...with two semi-straightened fish hooks...tapped by a secondary hammer with the unwavering precision of a sewing machine. During the more painful moments, our skilled tormentors would cluck commiseratingly into our ears." ♢

Penan Music, Art and Culture

The Penan have a rich musical tradition. All of their instruments are made from wood and bamboo. Five types are commonly played: the mouth organ (kelure), jaw harp (oreng), flute (kringon), four-stringed instrument (pagang), and the lute (sape). The kelure is fashioned from a dried gourd fitted with six bamboo pipes of varying lengths and produces a flute-like sound. The oreng is a carefully carved wooden jaw harp, weighted with resin and shaped to create vibrating tongues that enhance its tone. The pagang, made from a length of bamboo, is played only by women. These instruments accompany both solo and group dances, performed to their rhythmic sounds. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Traditionally, deep in the rainforests, where electricity was unaccessible and people didn’t have television, nomadic Penan entertained themselves by play music, dancing and singing. The capture of a wild boar was reason for celebration. At night the Penan, clad in hornbill feathers, sing and dance to"Borneo bluegrass" music produced with bamboo nose flutes, vine stringed instruments made from animal skins and sing from toothless howling old ladies. Young boys flirt with girls by wiggling their ears and when couple pair off they sometimes head to the river to make love. During important festivals shaman go off into a "dream wandering" trance in which they speak in a language that only the gods can understand. "The mysterious Penan water music," Blair wrote, "which few had heard and none could describe, [was] and alluring symbol of lost forest maidens." The syncopated rhythms are played by a half dozen or so children using cupped hands. ♢[Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

One traditional Penan morning song goes:

Wake up, don’t you hear the gibbon?

It’s time to go hunting.

I will stay and prepare to cook what you bring.

You wake up in the morning before the clouds rise up in the sky.

You are already moving like the leopard, through the hills and mountains.

But I am still not prepared for your return.

[Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Smithsonian magazine, March 2016]

The Penan are renowned craftspeople and produce some of the finest rattan mats and baskets in Borneo. Women weave baskets, mats, backpacks, bracelets, and decorative items with intricate black-and-white patterns, while men are skilled blacksmiths who make highly valued blowpipes. Weaving mats and baskets involves splitting rattan into strips of different widths, dyeing them, and hand-weaving them into finely patterned geometric designs. Penan handicrafts, together with forest products such as camphor and gaharu, have traditionally been traded for salt, metal tools, clothing, and cooking utensils. ^^

Penan Folklore, Myths and Inspiration from Nature

The Penan also have a rich tradition of stories. Penan folklore includes a rich body of myths, legends, and epics, though much of this oral tradition has been lost as younger generations show less interest. The best-known epic is Oia Abeng, now surviving only in fragments. Among popular folktales is that of Bale Gau, the god of thunder, who can turn people into stone. According to belief, animal spirits angered by human disrespect may call on Bale Gau to punish offenders, and many ancient rock formations are said to be people transformed into stone for mocking animals in disguise. ^^

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Smithsonian magazine: I’ve heard a Penan myth about leeches — how demons create them out of the veins of dead people. Ian Mackenzie, an ethnographer and linguist who has lived with the Penan on and off for almost 25 years, the source of this story, told me it took him a long time to gather traditional teachings like this. “The missionaries had anathematized the old beliefs, so most people had willfully forgotten them,” he said. “After seven years, I came to a group I’d never visited. There I met Galang, who, though nominally Christian, knew all the myths, and after some years trusted me enough to disclose the secrets of their cosmos, which contains seven or eight different worlds. Today, I am almost certain he is the last good Penan informant.” [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Smithsonian magazine, March 2016]

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Smithsonian magazine: At Long Mera’an, I meet Radu, a master sape player. Through a translator, he tells me he learned his melodies from the birds in the forest, messengers of the spirit Balei Pu’un. “The world was not created by Balei Pu’un,” says Radu. “It was already there. His job is to help people be good to each other. The way he communicates is through a bird or animal, because people cannot see him, so he needs a translator, a special person who is able to understand animals. My father was one of these people, and he taught me how to do it.”Is there a best time of day to hear Balei Pu’un speaking through the animals? “No time of day is better. If it happens, it happens.” [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Smithsonian magazine, March 2016]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026