DAYAKS

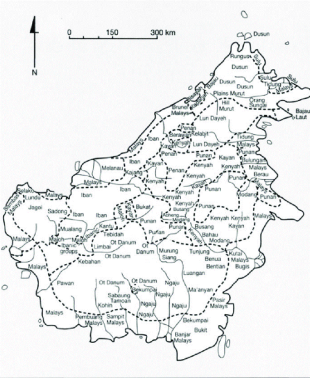

The indigenous people inhabiting the dense tropical rainforests of Borneo are collectively called the Dayaks. There are many Dayak tribes that are diverse in culture as well as in language. The word “Dayak” actually means “inland” or “upriver”, especially where the Indonesian part of Borneo, — called Kalimantan, — is cut by many long and wide rivers as well as many tributaries, that are used as transportation highways.

Hundreds of different Indigenous groups, cultures and languages in Borneo are loosely grouped under the term "Dayak". "Dayak" is sometimes used as a collective label for non Muslim Austronesian Indigenous peoples of Borneo. This grouping includes the Iban and Bidayuh peoples of East Malaysia, as well as the Kayan, Kenyah, and Ngaju peoples of Kalimantan.

Even a broad classification of Dayak peoples reveals considerable diversity. These include the nomadic Punan of the remote interior forests; the Murut-Kadazan of Sabah and neighboring parts of Indonesia, whose languages are most closely related to those of the Philippines; the Lun Dayeh and Lun Bawang, who are culturally linked to the Kelabit of Sarawak; the Kayan and Kenyah of eastern Kalimantan; and the Land Dayaks and Sea Dayaks, or Iban, of western Kalimantan, who speak Malay dialects but do not share Islamized Malay culture. Also included are the large Barito River groups of central Kalimantan, such as the Ma’anyan, Ngaju, Ot Danum, Benuaq, and Tunjung. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Dayak Groups

The most prominent Dayak groups that live in Central Kalimantan are the Ngaju Dayaks, the Lawangan, the Ma’anyan and the Ot Danum, known as the Barito Dayaks, named after the Barito river. Among these, the most dominant are the Ngaju, who inhabit the Kahayan river basin by the present town of Palangkaraya. The Ngaju are involved in agricultural commerce, planting rice, cloves, coffee, palm oil, pepper and cocoa, whilst, the other tribes still mostly practice subsistence slash and burn agriculture.

The Ot Danum tribe inhabits a region of the Kahayan River, north of areas occupied by the Ngaju and south of the Schwaner and Muller mountain ranges. They live in long houses built on two- to five-meter-high meter pillars above the ground. One exceptionally large house has around 50 rooms. These longhouses are locally known as betang. The Ot Danum are known for their skill plaiting rattan, palm leaves and bamboo. Even today they still continue do follow the ways of their ancestors. [Source:Indonesia Tourism Board]

The Ma’anyan Dayak tribe retain their traditional beliefs about the spirit world and continue to practice old agricultural rituals and complex mortality ceremonies and employ shaman as healers. Their cemeteries indicate social hierarchy. The cemetery of the nobility is located in the most upstream position of the river, followed by warriors. Ordinary folk are buried further downstream, slaves further still.

History of the Dayaks

By 3000 B.C., Austronesian peoples from the Philippines—farmers and seafarers—had arrived in Borneo. Beginning in the sixth century A.D., iron metallurgy provided the Dayaks with tools to clear the dense interior forests for rice and taro cultivation. These crops were more nutritious than their former staple, sago palm starch. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Since the early centuries A.D., the Dayak people have supplemented their subsistence agriculture by procuring forest products. These include gold, diamonds, gutta-percha, illipe nuts (a source of a valued oil), aloeswood (an aromatic resin), camphor, bezoar stones (the hardened gallbladders of certain monkeys), and other ingredients for Chinese herbal medicines.

Traditionally, the Dayaks traded these products with coastal brokers in exchange for goods such as Javanese gongs, Chinese porcelain, and silk. The most powerful brokers were the sultans, such as the ruler of Banjarmasin (see "Banjarese"), who controlled the river mouths and all traffic between the Borneo interior and the outside world. Despite the claims of the sultans of Banjarmasin to suzerainty over the peoples living upriver in Central Kalimantan, the latter remained de facto independent, living in small, semipermanent settlements scattered over a vast area. ^

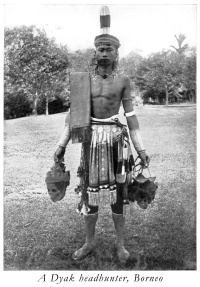

The Dayaks are former head hunters and the original "wild men of Borneo" and sometimes displayed as such in traveling shows in the U.S. and Europe. They continued to practice headhunting after it was outlawed by the Dutch in the 19th century. Beginning in the 1830s, the Dutch colonial administration actively encouraged Protestant missionary activity among Dayak communities. This policy slowed the spread of Islam, strengthened a sense of distinct identity among interior peoples, and contributed to the emergence of a Christianized Ngaju elite.

Up until World War II most Dayaks were river-dwellers. Now many have been Christianized and forced into settlements. Even though they were the original inhabitants of Borneo they are now greatly outnumbered by Malays and other Malaysian and Indonesian groups. It is believed that most Dayaks lived along the coast until they were driven inland after the arrival of the Malays.

During World War II the Japanese occupied Borneo and targeted the so-called Kapit Division in southern Borneo, which had many Dayak members. This ill-treatment sparked the Dayaks to join with the allied forces against a common enemy. A group of American and Australian military leaders trained the Dayak in guerrilla warfare in the jungle. During the ensuing years the Dayak managed to capture or kill 1,500 Japanese and fed the Allies vital intelligence about Japanese held oil fields.

After the 1987 state elections, the rise of Dayak nationalism in Sarawak was also considered a threat to political stability, but it had been diffused by the 1991 elections. In 1991, the Sarawak Native People’s Party (PBDS, Parti Bansa Dayak Sarawak) retained only seven of the fifteen seats it had won in 1987. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Dayak Languages

Dayaks speak a great variety of related languages and dialects and have a great deal of cultural variation but little political unity. Because of this anthropologist have had great difficulty figuring out how to categorize, distinguish and group the various Dayak groups.

The Ngaju Dayak language belongs to a group of closely related Austronesian languages called the Barito family. It is spoken from the Schwaner Mountains and the upper Mahakam valley to the southeast corner of Borneo, excluding the territory of the people who speak the language called Banjarese. The Kahayan dialect, called Bara-dia after its words for "have" and "not," has become a lingua franca throughout much of Kalimantan. Other major Barito languages include Ot Danum, Lawangan, and Ma'anyan. Interestingly, a Ma'anyan dialect appears to be the ancestor of the Malagasy languages. Around the fifth century, the Barito Dayaks lived closer to the coast and participated in long-distance seafaring under Malay leadership. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

James Brooke wrote in the 1840s in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: With respect to the dialects, though the difference is considerable, they are evidently derived from a common source; but it is remarkable that some words in the Millanow and Eayan are similar to the Bugis and Badjow language. This intermixture of dialects, which can be linked together, appears to be more conclusive of the common origin of the wild tribes and civilised nations of the Archipelago than most other arguments; and if Marsden's position be correct (which there can be little or no reason to doubt), that the Polynesian is an original race with an original language, 1 it must likewise be conceded that the wild tribes represent the primitive state of society in these islands. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

Dayak Religious Beliefs

Most Dayaks tend to practice either Protestantism or Kaharingan. The latter is a form of indigenous religious practice blending animism and ancestor worship classified by the Indonesiea government as Hindu and labeled Hindu-Bali Kaharingan. Although many Dayaks have modernized and converted to Christianity and Islam, the majority still adhere to the original Kaharingan belief.

Kaharingan belief focuses on the supernatural world of spirits, including ancestral spirits. For this reason, funeral rites and structures are elaborate. Most essential, however, are the secondary funeral rites, called tiwah, when the bones of the deceased are exhumed, cleaned and placed in a special mausoleum, called sandung, which are placed next to remains of their other ancestors. These coffins are normally beautifully carved and adorned. The tiwah is believed to be a most essential ceremony to allow the soul of the deceased finally to be released to the highest heaven.

Through its healing performances, Kaharingan serves to mold the scattered agricultural residences into a community, and it is at times of ritual that the Dayak peoples coalesce as a group. There is no set ritual leader, nor is there a fixed ritual presentation. Specific ceremonies may be held in the home of the sponsor. Shamanic curing, or balian, is one of the core features of these ritual practices. Because illness is thought to result in a loss of the soul, the ritual healing practices are devoted to its spiritual and ceremonial retrieval. In general, religious practices focus on the body, and on the health of the body politic more broadly. Sickness results from giving offense to one of the many spirits inhabiting the earth and fields, usually from a failure to sacrifice to them. The goal of the balian is to call back the wayward soul and restore the health of the community through trance, dance, and possession. [Source: Library of Congress, 2006]

Kaharingan is the name of a spring associated with an “elixir of life,” and secured its official classification as a branch of Balinese Hinduism. Kaharingan is said to have about 330,000 adherents. A sixteen-member council, composed almost entirely of Ngaju, oversees theology and ritual practice, although it does not include balian or basir. Balian can refer to priestesses and basir are transvestite priests, Through a three hundred–page study book published in 1981, the construction of Hindu-Balinese-style meeting halls, and the use of sermons, prayers, and hymns, the council promotes ideas of a supreme being and individual salvation. It has also encouraged the widespread identification of the important deity Tempon Telon with Jesus Christ. Today, no tiwah ceremony may be held without registration with the council, which in turn instructs the police to issue the necessary permit. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditional Dayak Religious Beliefs

Dayak "psycho-navigators” use visions and dreams to help them find their way in the forest. Dayak shaman practitioners of the "Old Snake religion” describe a hidden highland lake where enormous aging pythons enjoy dancing under the light of the full moon to honor the forest god Aping. Many Dayaks are Christians who have incorporated animists concepts onto their belief scheme. Missionaries went through the trouble of backpacking in paints and brushes to make hellfire scenes on the sides of longhouses. On the positive side missionaries have helped the Dayak clear landing strips which can be used for medical emergencies. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

In the 1840s, Henry Keppel wrote in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “Her Fanshawe and a party of Cruisers, returned from a five days' excursion amongst the Dyaks, having visited the Suntah, Stang, Sigo, and Sanpro tribes. It was a progress; at each tribe there was dancing, and a number of ceremonies. White fowls were waved as I have before described, slaughtered, and the blood mixed with kuny-it, a yellow root, which delightful mixture was freely scattered over them and their goods by me, holding in my hand a dozen or two women's necklaces. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

"Amongst my Dyak inquiries, I found out that the name of their god is Tuppa, and not Jovata, which they before gave me, and which they use, but do not acknowledge. Tuppa is the great god; eight other gods were in heaven; one fell or descended into Java, — seven remained above; one ef these is named Sakarra, who, with his companions and followers, is (or is in) the constellation of a cluster of stars, doubtless the Pleiades; and by the position of this constellation the Dyaks can judge good and bad fortune. If this cluster of stars be high in the heavens, success will attend the Dyak; when it sinks below the horizon, ill luck follows.; fruit and crops will not ripen; war and famine are dreaded. Probably originally this was but a simple and natural division of the seasons, which has now become a gross superstition.-

The Dayaks consider orangutans to be the equals of humans, and they are treated with the same respect as neighboring tribes. The Dayak believe that loners belong to the tribe of the gibbons and gregarious people are kin to the orangutan. The Dayak practiced tattooing as a religious art but the practice has been banned by the Indonesian and Malaysian government.

Dayak Headhunting in the 19th Century

In the 19th century, Brooke government on Sarawak described war parties of Dayak tribes such as the Iban and Kenyah people taking enemy heads and keeping them. Yet later on, with the exception of massed raids, the practice of headhunting was limited to individual retaliation attacks.

Henry Keppel wrote in“Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: Some of the Singe Dyaks succeeded in taking the heads of a few pirates, who probably were killed or wounded in the forts on our first discharge. I saw one body afterwards without its head, in which each passing Dyak had thought proper to stick a spear, so that it had all the appearance of a huge porcupine. The operation of extracting the brains from the lower part of the skull, with a bit of bamboo shaped like a spoon, preparatory to preserving, is not a pleasing one. The head is then dried, with the flesh and hair on it, suspended over a slow fire, during which process the chiefs and elders of the tribe perform a sort of war-dance. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “The Kayans of the north-west coast of Borneo have one custom in common with the wild tribe of Minkoka in the Bay of Boni. Both the Kayans and Minkokas on the death of a relative seek for a head; and on the death of their chief many human heads must be procured: which practice is unknown to the Dyak. It may further be remarked, that their probable immigration from Celebes is supported by the statement of the Millanows, that the Murut and Dyak give place to the Kayan whenever they come in contact, and that the latter people have depopulated large tracts in the interior, which were once occupied by the former. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

Carl Bock wrote in “Headhunters of Borneo” (1881): ““The barbarous practice of head-hunting, as carried on by all the Dyaks tribes, not only in the independent territories, but also in some part of the tributary states, is part and parcel of their religious rites. Births and “ naming,’’ marriages and burials, not to mention less important events, cannot be properly celebrated unless the heads of a few enemies, more or less, have been secured to grace the festivities or solemnities. Head-hunting is consequently the most difficult feature in the relationship of the subject races to their white masters, and the most delicate problem which civilization has to solve in the future administration of the as yet independent tribes in the interior of Borneo. The Dutch have already done much by the double agency of their arms and their trade to remove this plague-spot from the character of the tribes more immediately under their control.”

Dayak Funerals

The Dayak perform elaborate death ceremonies in which the bones are disinterred for secondary reburial. The Ngaju Dayaks in the Mendawai area of Kalimantan keep alive their ancient burial rituals called Tiwah. Participants wear bizarre masks, sing, stage mock attacks. They exhume the bones of the dead, anoint and touch the bones and re-intern them in family “sandung”. (House-shaped boxes on stilts). In the old days headhunting was often include in the ritual.

Tiwah ceremonies are held in certain areas maybe once or twice a year with really big ones every five year or so. Numerous families participate and sometimes more than 150 bodies are exhumed. Feasting sometimes lasts for a month. The climax is when the bones are taken from the grave washed and purified. Water buffalo, pigs, chickens, and other animal are sacrificed for the journey to afterlife. To ensure a pleasant afterlife, relatives of the deceased fill boats with food and rice wine and carved servants to accompany the dead in the afterworld.

The “ijambe” of the Ma’anyan and Lawangan Dayaks is similar. The bones however are cremated and the ashes are placed in small jars in family apartments. In the Wara ceremony of the Tewotan, Baya, Dusun and Bentian Dayaks, a medium is used to communicated with the dead.

The Dayaks have traditionally believed that the black hornbill carries the human soul to the afterlife. Hornbill beaks and skulls are still immersed in water overnight, with the Dayak believing that whoever drinks the liquid will gain special powers. Some Dayaks keep young hornbills as pets and release them when they become adults to mate.

Character of the Dayaks

Harrison W. Smith wrote in a February 1919 National Geographic article, “s with most of the Sarawak tribes, personal cleanliness is the rule, The Dayaks have been known to comment on a white traveler to the effect that, although he seemed to be otherwise all right, he did not bathe as frequently as they considered necessary.

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy” in the 1840s: “There are twenty tribes in Sarawak, on about fifty square miles of land. The appearance of the Dyaks is prepossessing: they have good-natured faces, with a mild and subdued expression; eyes set far apart, and features sometimes well formed. In person they are active, of middling height, and not distinguishable from the Malays in complexion. The women are neither so good-looking nor wellformed as the men, but they have the same expression, and are cheerful and kind-tempered. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“In character the Dyak is mild and tractable, hospitable when he is well used, grateful for kindness, industrious, honest, and simple; neither treacherous nor cunning, and so truthful that the word of one of them might safely be taken be- fore the oath of half-a-dozen Borneons. In their dealings they are very straightforward and correct, and so trustworthy that they rarely attempt, even after a lapse of years, to evade payment of a just debtor On the reverse of this picture there is little unfavourable to be said; and the wonder is, they have learned so little deceit or falsehood where the examples before them have been so rife.-

“The temper of the Dyak inclines to be sullen; and they oppose a dogged and stupid obstinacy when set to a task which displeases them, and support with immovable apathy torrents of abuse or entreaty. They are likewise distrustful, fickle, apt to be led away, and evasive in concealing the amount of their property; but these are the vices rather of situation than of character, for they have been taught by bitter experience that their rulers set no limits to their exactions, and that hiding is their only chance of retaining a portion of the grain they have raised. They are, at the same time, fully aware of the customs by which their ancestors were governed, and are constantly appealing to them as a rule of right, and frequently arguing with the Malay on the subject. Upon these occasions they are silenced, but not convinced; and the Malay, whilst he evades, or bullies when it is needful, is sure to appeal to these very much-abused customs whenever it serves his purpose.-

“The manners of the Dyaks with strangers are reserved to an extent rarely seen amongst rude or half-civilised people; but on a better acquaintance (which is not readily acquired), they are open and talkative, and, when heated with their favourite beverage, lively, and evincing more shrewdness and observation than they have gained credit for possessing. Their ideas, as may well be supposed, are very limited; they reckon with their fingers and toes, and few are clever enough to count beyond twenty; but when they repeat the operation, they record each twenty by making a knot on a string.-

“Like other wild people, the slightest restraint is irksome, and no temptation will induce them to stay long from their favourite jungle. It is there they seek the excitement of war, the pleasures of the chase, the labours of the field, and the abundance of fruit in the rich produce which assists in supporting their families. The pathless jungle is endeared to them by every association which influences the human mind, and they languish when prevented from roaming there as inclination dictates.-

Ngaju Dayaks Agriculture, Hunting and Economic Activity

Most Dayaks sustain themselves through swidden, or shifting-cultivation, agriculture, growing dry rice along with a variety of other crops, including cassava, ubi rambat (a creeping tuber), taro, eggplant, pineapple, banana, sugarcane, chili, gourds, and occasionally tobacco. This form of agriculture depends on cooperation among families. Men generally carry out most of the fieldwork, although women also work in the fields, particularly in households that have lost adult men due to death or other circumstances. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Among Dayak groups, the Ngaju have been pioneers in cultivating cash crops on permanent fields, especially rattan and rubber, as well as cloves, oil palm, coffee, pepper, and cacao. Pigs and chickens are raised primarily for ritual use. River fishing is the main source of protein and is more important than hunting, which includes spearing wild pigs with the help of dogs and shooting birds with blowguns. Hunters also employ snares and traps fitted with wooden or bamboo spikes.

In addition to agriculture, the Ngaju sell forest products to coastal traders. These include valuable timbers such as ironwood (ulin), damar resin, kulit gemur, which is used in cosmetics and insect repellent, and illipe nuts. Metalworking among the Dayak is highly developed, particularly in the production of the mandau, a type of machete or parang. The blade is forged using a combination of softer iron for flexibility and a narrow strip of harder iron inserted into the cutting edge for sharpness, a technique known as ngamboh. Designed for both combat and forest use, the mandau is relatively short and carried with its cutting edge facing upward. A protrusion on the handle allows it to be drawn rapidly with the side of the hand, enabling an exceptionally fast and efficient drawing motion.

Dayak and the Modern World

Many Dayaks now wear Western clothes, watch television and ride around on motorbikes. Their traditional homes sometimes have satellite dishes. Few live in longhouses anymore. Their traditionally dugouts have motors. Many Dayaks would like to create their own independent state. Dayak chiefs have met to discuss the subject.

The Dayaks are regarded as one the most marginalized ethnic groups in Indonesia and Malaysia. They have been driven off their land by logging schemes, palm oil plantations, deforestation, settlers form other ethnic groups and transmigration schemes. They have been forced to move from their river villages to towns, often dominated by other ethnic groups. They claim they have been denied jobs, education and land and that settlers to their traditional lands are given preferences to these things. . The Dayaks are perceived by other ethnic groups as backward, stupid and lazy. They often occupy the lowest rungs of the economic ladder. The logging companies and palm oil estates prefer to use migrant laborers rather than Dayaks. Forced into the cities the Dayaks often find no work at all. To earn money, many Dayaks pan gold from the rivers in Borneo and tap rubber trees. Lucky ones get dangerous jobs in gold, tin and copper mines or at palm oil and coconut plantations.

Dayaks that remain in the forest have been hurt by drought, fires and soil erosion, The forests fires in the late 1990s were particularly devastating for them. Their villages were engulfed in flames and smoke, and trees and plants they depended on for food destroyed. But not only that, developers used the fires as an excuse to clear land that belonged to the to the Dayaks. Droughts have traditionally been blamed on mothers who married their son—and end when they are both killed.

The Bintangor tree, which grows in swamps in Sarawak, produces a kind latex that in turn contains chemicals that have been shown to be effective treating AIDS and HIV. The Dyaks traditionally used the latex to make poultice that treated headaches and skin rashes as well as a poison for stunning fish. The drug company and the state of Sarawak have an agreement to share any profits made from the drug but under the arrangement the Dyaks get nothing.

Impact of Timber Logging and Forestry on the Dayaks

Sinapan Samydorai of Human Rights Solidarity wrote that Kalimantan has been severely affected by logging and the expansion of timber plantations for the pulp and wood industries. Indigenous Dayak communities have resisted the seizure of their lands and the destruction of their traditional livelihoods. [Source: Sinapan Samydorai, Human Rights Solidairty, August 14, 2001

In Kutai District, East Kalimantan, villagers from Menamang challenged a planned 198,000 hectare timber plantation proposed by a joint venture involving PT Surya Hutani Jaya, PT Sumalindo Lestari Jaya, and the state forestry company Inhutani 1. The conflict began in 1992, when 1,663 hectares of customary land belonging to 294 villagers were taken. Crops, fruit trees, and rattan gardens were destroyed. In January 1996, three villagers traveled to Jakarta to bring their case to the National Human Rights Commission. They reported torture and intimidation by security forces after refusing compensation, which was later found to be unpaid and supported by forged documents. Some villagers accepted compensation, while others faced continued abuse.

Also in East Kalimantan, the Bentian Dayak community of Jelmu Sibak opposed PT Kahold Utama, which occupied more than 1,600 hectares of their land to establish a timber estate using transmigration labor. The project destroyed crops, forest resources, honey trees, rattan, ancestral graves, and disrupted water sources. In 1995 and 1996, Bentian representatives and supporting nongovernmental organizations submitted complaints to local authorities, government ministries in Jakarta, and the National Human Rights Commission, citing violations of customary land rights affecting 72 families. Efforts to resolve the case were constrained by the company’s political connections.

In West Kalimantan, Dayak villagers in Belimbing, Sambas District, faced similar pressures. In early 1995, PT Nityasa Idola began clearing 120 hectares of customary land for a pulpwood plantation. Villagers were ordered to stop farming and were threatened with imprisonment. After repeated attempts to seek official intervention failed, villagers burned the company’s seedling camp in November 1995, one of several such attacks against timber plantation developers in the region during that period.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026