IBAN SOCIETY

The Iban are a group of former forest people that are found throughout Borneo but are particularly concentrated in Sarawak. Also known as Dayaks and Dyak, they have traditionally lived along the mid levels hills and delta plains of Borneo and are The largest of Sarawak's ethnic groups, making up about 30 percent of the state's population. In the old days they practiced headhunting.

The basic social unit of Iban society is the bilik-family, usually made up of five or six related people. Traditional Iban longhouse society revolves around a group of siblings who founded the house or their descendants. They are the leaders of the house and they decide how bilik-families occupy each apartment. The closeness of apartments and houses is often a refection of kinship or alliances. A longhouse chief is called a “tuai rumah”. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

When an Ibam couple marries, their children may belong to either the wife’s or the husband’s family, depending on marriage arrangements. Iban families are part of a broad and flexible kinship system shaped by frequent movement and migration. Close kin groups include those related through grandparents, extending to first cousins. Beyond this, the Iban also recognize wider networks of mutual obligation that may include distant relatives, non-kin, and even non-Iban, as long as they share reciprocal rights and duties. Larger social circles consist of distant kin who participate in each other’s festivals and communal meals. Descent and family ties are traced through both the mother’s and father’s lines. Although some Iban can trace ancestry back many generations, genealogies are often selectively constructed to create or reinforce social connections, even with people who were originally strangers.~

The Iban have traditionally been more egalitarian that other Bornean groups whose members are more rigidly divided into aristocrats, commoners and slaves. The Iban are aware of the long-standing distinctions in status among themselves. They recognize three groups: the Raja Berani (the wealthy and brave), the Mensia Saribu (the commoners), and the Ulun (the slaves). Descendants of the first status still enjoy prestige, while descendants of the third are still disdained. Iban political positions such as headmen, regional chiefs and paramount chief were introduced by the British in the 19th century for administrative purposes and help suppress headhunting. The traditional Iban legal system is based on paying fines in traded goods such as brassware, ceramics, and more recently outboard motors, firearms and money. Young people who traveled and acquired these items were greatly esteemed. _

Egalitarianism permeates almost all social relations, including those between men and women. As with men, Iban women play a significant role in maintaining the family unit. Their main duties are nurturing the family, including looking after the children when they are young. In addition to managing the home, Iban women are required to work in the fields, especially during planting and harvesting seasons. They manage their farms with their husbands. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

RELATED ARTICLES:

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Iban Customs and Etiquette

Like other communities in Sarawak, social interactions in the Iban community are governed by adat. Adat encompasses a variety of customs and practices, as well as basic values and a religious system that govern life in the longhouse. Adat shapes relations between people and their environment and forges a path between humans and the spirit world. Adat also governs interpersonal relations between individuals. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Among the Iban, it is considered indecent to blow one's nose or spit while someone else is eating, or even to mention something dirty. When passing someone seated in the longhouse, it is polite to bow your head, place your hands between your knees, and say, "Please excuse me. I wish to walk in front of you." ^^

The Iban have great respect for visitors. It is customary to invite visitors passing the longhouse or landing place to come inside and enjoy a snack of betel nuts. Offering betel nuts is the traditional Iban welcome in the gallery. If the visitor has not eaten, food is served. An Iban who does not take care of visitors is considered greedy. ^^

The Iban are taught from an early age to avoid conflict. Children are told that guardian spirits are always watching them to make sure they behave correctly. One of the main duties of a headman is to arbitrate over disputes. The Iban can be a proud and stubborn people, and conflicts break out over property, sexual impropriety and perceived insults. In the old days these matters were sometimes “solved” through headhunting. The Iban have traditionally had a fierce rivalry with the Kayah.

Iban Marriage and Family

Both arranged marriages and love matches are common. Parents prefer the former as a way of improving alliances within the longhouse community. Marriages within a kin group are preferred to maintain possession of property. Divorces are easy to get. Non-Iban ethnic groups have been absorbed into the Iban community through marriage and are regarded as Iban by the second generation. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Iban families are usually relatively small and are conceived as a permanent unit —. continuation of a bilek (a section of the longhouse).The bilik-family that occupies a particular place in an Iban longhouse is usually a nuclear family but can also contain grandparents or members that joined through adoption or other means. They are responsible for constructing their parents apartment in the long house and producing their own apartment and governing their own financial affairs. In each generation, one son or daughter is expected to remain in the bilek after marriage to ensure the survival of the family unit and to assume responsibility for managing its ritual obligations and economic resources.

Typically the father, is responsible for protecting family interests and representing its members in disputes with other families. When a family member commits an offense, any fines are usually paid from shared family resources, reflecting the belief that individual actions affect the family as a whole. Each member therefore carries a responsibility to maintain family honor. In regard to inheritance, both male and female children share equally in rights to real and other property so long as they remain members of their natal bilik.

Young children are generally lavished with attention and allowed to run free. By age 5 they wash their own clothes; by age 8 girls are doing domestic chores. Boys have traditionally left the longhouses for months or years and were expected to return with trophies. Girls are expected to become skilled weavers. Iban that can afford it send their children to boarding schools down river. The children that have done this say they prefer their school dormitories, with electricity and running water to the long houses. Many have vowed to move to the cities to find work and leave the traditional Iban life behind.

Iban Rites of Passage

A child is not given a name immediately after birth, but is called ulat (baby). Babies are usually named after their grandparents and/or their grandparents' cousins. After a name is given, the bathing ceremony is performed at the river. By age five, children wash their own clothes, and by eight, girls help with domestic chores. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

A girl is considered to have reached puberty at age 10 and is expected to sleep alone until she is married. Meanwhile, a boy of the same age moves to sleep in the gallery with the other bachelors. In the past, boys had to undergo circumcision, though it was not a ceremonial event. Girls are taught to cook, pound, and unhusk rice at age seven, while boys accompany their fathers on hunting trips. By the age of 13, girls learn to weave, while boys learn to gather and split firewood with an axe. This training prepares them for marriage. ^

Traditionally, adolescent males would undertake "the initiate's journey," a trip lasting several months or years. Upon their return, they were expected to bring back trophies. Adolescent females demonstrate their maturity through diligence in weaving ceremonial cloths, baskets, and mats.

The birth of a first child marks the transition from adolescence to adulthood, signifying a change in status. The new parents are no longer called by their personal names, but rather by relational names: "apai," meaning "the father of," and "indai," meaning "the mother of." ^^

When an Iban dies, they are said to become a spirit (antu). Complicated death rites are observed to ensure harmony between the spirits and the living and to ensure the future welfare of both. Many rites are performed. The final rite, the Gawai Antu, is the most important. During this rite, a tomb house is built over the grave of the deceased to serve as a home for the spirit. ^

Iban Life

Many indigenous peoples of interior Sarawak, including the Iban, traditionally have lived in longhouses. Today, however, there are clear differences between Iban communities in urban areas who live like other urbanized people and those who continue to reside in longhouses in the interior. The longhouse as a whole is led by a tuai rumah (longhouse headman), who is expected to be a man of ability and respected standing. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

From an early age, life in the longhouse fosters a strong sense of belonging among the Iban. As a result, loyalty to the longhouse often remains strong throughout life, second only to allegiance to the immediate family. While many longhouses today have access to electricity and piped water, some still lack these basic facilities. In such cases, residents depend on nearby rivers for water and use kerosene lamps for lighting at night.

The Iban recognize education as essential for success in the modern world and as a pathway to social mobility and security. In accordance with Malaysian government policy, Iban children are required to attend school from the age of six, and education is strongly encouraged for both boys and girls. Consequently, literacy rates among the Iban rose from 3 percent in 1947 to 35 percent in 1980 and nearly 49 percent by 1990. Today, many Iban are literate and have earned degrees from both local and overseas universities. With these qualifications, Iban individuals now occupy prominent roles in public service and the private sector, including positions as policymakers, corporate managers, academics, doctors, and lawyers.

The Iban love water. They sometimes spend all day squatting in rivers. In the old days they settled disputes by holding competitions to who could stay submerged under water the longest. Keeping animals as pets is rare among the Iban, as it is among many other indigenous groups in Borneo. Animals such as pigs and chickens are raised primarily for food, dogs are kept for hunting, and cats are valued for their practical role in controlling rodents in farms and longhouses.

Iban Longhouses

The Iban have traditionally lived in longhouses that are like villages under one roof. They can range in size from four families with 25 residents to 80 families with 500 residents. In the center of house is a common room off which the rooms of the house radiate, sort of like side streets off of the main square. Longhouses made sense in the old days because the were easier to defend than dwelling spread out all over the place. They were regarded as normal and single family houses were seen as unusual. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

A longhouse resembles a row of terraced apartments raised on wooden pillars, typically between 1.2 and 2 meters (4 and 7 feet) above the ground, for protection and safety. It consists of a series of family bileks (apartments) built side by side and connected by shared passageways, galleries, and ruais (open-air verandas). Each bilek is owned and maintained by a single family, including their section of the gallery and veranda. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Iban longhouses have a large open deck in front, and a wide enclosed veranda, with doors leading to the individual biliks. The long veranda has traditionally been the center of the traditional social life. It is where old people gathered in the evening to chat, weave rattan baskets, repair fishing nets and relax while their children watched television powered by a Honda generator. The porch is where clothes are hung and rice is dried. To get to the porch you walk up a rough ladder formed from a single log.

Longhouses are constructed with their front to the water, preferably facing east. The quality of construction often varies from group to group and even house to house within a village. High-quality ones are soundly built and have polished hardwood floors. Lower quality ones have walls and floors made of flimsy split bamboo. The average width of a family unit is 3.5 meters but the the distance from front to back can vary greatly.

The residents eat and sleep and store their heirlooms in their apartments. They sleep on straw mat floors in one room and eat around an open cooking fire in another. About halfway over the apartments and halfway over the veranda is loft where rice is stored and a large bark bed where unmarried girls sleep.

Iban Food

Rice is the staple food of the Iban in Sarawak and is eaten three times a day, usually accompanied by wild vegetables or meat gathered from the forest. Women typically collect edible plants such as mushrooms, fern shoots, and young leaves, while men provide meat through hunting or fishing. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Common dishes include stews made from plantain and papaya, which are eaten by using small balls of moist rice to scoop up the food. The Iban also drink a strong, sour rice wine known as tauk. During daily life, dogs, chickens, and children move freely around the household, although valued gamecocks are usually tethered near their owners’ doors.

The family normally comes together for the evening meal, sitting in a circle on a mat. Dishes—at least one vegetable and one meat or fish dish—are placed in the center and shared. Rice may be served on plates or wrapped in leaves and eaten by hand or with a spoon. The shared dishes are taken with a communal spoon used only for serving, not for eating. Water is usually drunk after the meal, and cleaning the kitchen and washing utensils are generally the responsibility of women.

In addition to brass cookware, the Iban traditionally use bamboo and leaves for cooking and serving food. One distinctive method involves cooking meat or vegetables in bamboo. The meat is seasoned with salt, ginger, and lemongrass, stuffed into a bamboo tube about 38 centimeters (15 inches) long, and sealed with young tapioca leaves to enhance the aroma. The bamboo is placed over a fire and turned constantly to prevent burning, and the dish is served with rice.

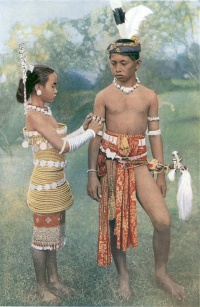

Iban Clothes

Today, most Iban men and women wear Western- or Malay-style clothing in their daily lives. Women commonly wear blouses and skirts or traditional Malay attire such as the baju kurung and kebaya. Traditionally, the Iban favor earthy tones such as brown and brick red, accented with indigo-blue dyes derived from tree roots and leaves. These colors are especially evident in pua kumbu, the renowned handwoven cotton textile that holds cultural and ritual significance. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

A traditional Iban woman’s attire includes the bidang (a tubular sarong-style skirt), kain pandak (short skirt), or kain tating (a weighted short skirt). Her costume may be completed with a rawai (a corset made of rattan or brass), a sugu tinggi (silver headdress), a marik empani (beaded collar), a selampai (sash or shawl), and various silver necklaces, bracelets, and anklets. Traditional men’s dress consists of a kelambi or baju burung (a woven cotton jacket decorated with symbolic designs) worn with a sirat (loincloth). Men may also wear a labong (embroidered turban) or a rattan cap adorned with feathers, along with a dangdong (shoulder shawl), a sword, silver bracelets, and ivory armlets.

The full splendor of traditional Iban costume is most clearly seen during the Gawai Dayak festival. On this occasion, young men and women dress in elaborate ceremonial attire and take part in costume parades, during which a kumang gawai (festival princess) and a keling gawai (festival prince) are selected.

One distinctive element of women’s traditional dress is the rawai, a tightly fitted corset made of cane hoops covered with small silver or brass rings and fastened with brass wire. It encases the hips, waist, and abdomen, restricting movement and giving the body a stiff, upright posture. Despite its rigidity, the rawai is regarded as highly elegant, especially when its silver surface is carefully polished.

Iban Agriculture

Iban have traditionally been rice farmers who used slash and burn methods on hills and slopes and grow food crops such as cassava, pumpkins and vegetables, raise cash crops like pepper and cacao and collect fruit from trees.Because of uncertainties of growing rice in Borneo, dozens of varieties are planted, a special sacred patch is set aside as a gift to an ancestor or spirit. The rice crop is planted and harvested by a single community at the same time to reduce the likelihood that a single family will have their fields damaged by pests. Different Iban communities have different cropping-fallow patterns. Many Iban cultivate food and collect plants from "managed" forest plots such as several varieties of ferns, bamboo shoots and hearts and pits from numerous palms. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The cultivating cycle is accompanied by numerous ritual to ensure a good harvest. At the end of April, the longhouse head convenes family leaders to decide on farm locations and the timing of initial rites. This coordination ensures that all rice matures at roughly the same time, reducing losses to pests and animals and allowing families to synchronize harvest rituals. Auguries are taken in June, fields are cleared in June and July, and burning takes place in August or September. When the rice ripens, rituals inform it that it will be harvested and brought back to the longhouse. On the final day of harvesting, offerings are made to the last stand of rice so that its soul will return home rather than remain in the field.

With fertilizers and pesticides Iban rely less on traditional methods and rituals than they used to. In the lowlands, Iban cultivate wet rice in permanent fields. In addition to rice, farmers grow gourds, pumpkins, cucumbers, maize, and cassava. Rice meals are supplemented with wild vegetables and fruits gathered from the forest. The Iban have problems with birds raiding their fields. To address this they set up rattles and noise makers in the fields that have strings attached to them that run to a small hut. When birds appear someone pulls on the strings which set off the noise makers that shoo away the birds.

Land rights are traditionally established through clearing, farming, or occupation. Use rights to farmland belong to the bilik-family and are held in perpetuity, maintained through the shared memory of longhouse residents. Boundaries are marked by natural features, trees, or planted bamboo lines. Apart from the land directly beneath the longhouse eaves, the community as a whole does not own land collectively. With the introduction of land surveys and formal titles in the early twentieth century, Iban living closer to administrative centers were able to secure legal recognition of family land rights. In recent decades, population growth and land commercialization have led some Iban to purchase land for investment and speculation.

Iban Fishing, Hunting and Decorated Pig Traps

Fishing has traditionally been the main source of protein, but logging and river siltation have sharply reduced fish stocks. Fishing is done with traps, nets and lines and hooks. Wild pigs, deer and other animals are hunted with dogs, traps and nets. Almost all families keep pigs and chickens. Every longhouse has dogs. Chickens, pigs and water buffalo are raised for sacrifices.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains some wood Iban tuntun pig-trap sticks. One probably probably made in the Sarebas-Krian region in the Late 19th-early 20th century measures 53.3 centimeters (21 inches). Eric Kjellgren wrote: Created intentionally to please the eye, tuntun, or pig-trap sticks, are unique to the Iban people of Borneo. While in some areas tuntun were simple rods, in many lban groups the shafts were crowned, as here, with human or animal figures depicting powerful spirits. The name tuntun means, literally, "at the right height," a reference to the primary function of the objects, which were used as measuring rods to determine the proper height for the trip wire in the animal traps known as peti. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Peti were spring traps, constructed from bent saplings which, when triggered, snapped straight, driving a sharpened bamboo blade into the quarry. Intended primarily for wild pigs, peti were also used for other game. The top of the tuntun shaft indicated the correct trip-wire height for a pig, and the top of the figure marked the height for a sambar deer; notches lower down on the shaft marked the settings for smaller species. Hazardous to humans as well as animals, peti were banned by the colonial authorities in the early twentieth century. This prohibition, together with the growing scarcity of wild pigs, led to the demise of the tuntun-carving tradition.

According to oral tradition, the art of making pig traps and tuntun was taught to the lban by a group of spirits led by SeGenun, who instructed them to make tuntun by cutting a stick measured from the crook of the elbow to the end of the middle finger. The variation in the lengths of surviving tuntun indicates that carvers likely followed SeGenun's instructions.

When setting a group of traps, an Iban hunter carried a single tuntun, attached to the outside of the sarong sia, a basket that held the bamboo blades for the traps and other necessary items. At each trap, the hunter inserted the tapered point of the tuntun into the ground to the base of the shaft and determined the height for the trip wire. He then made a small offering and prayed to the spirit portrayed on the tuntun, asking for its assistance in attracting game. Once all the traps were set, the hunter returned to the communal longhouse and hung the tuntun above the door to his apartment or at one of the longhouse entrances, from which the spirit figure was believed to call out to the pig or other game animal, enticing it into the trap.

Iban Economic Activity

The Iban have traditionally gather bamboo and rattan for household use and for sale. Other important forest products include natural rubber and the illipe nut, which is harvested approximately every four years. Ironwood, once widely used as logs or poles, has become increasingly scarce. Women are primarily responsible for domestic tasks such as cooking and caring for the bilik. Both men and women collect wild foods for household use and, near towns, for sale. Men typically handle tree felling, heavier agricultural work, fishing, hunting.

These days many Iban men work in logging camps or on rubber or palm oil plantations. Some work for oil companies; others as traders. Other work independently tapping rubber and collecting rattan. Many Iban men and women have gone to the cities in search of salaried jobs. Some Iban earn extra cash by putting up tourists in their longhouses and performing so-called headhunter dances to drums and gongs.

Most Iban people living in urban areas are employed in formal jobs. This is partly due to a traditional Iban custom known as bejalai, which encourages young Ibans to leave their longhouses in search of prestige and new experiences. Consequently, many have become professional workers, while others are factory workers in places like Singapore and Johor. Others work on offshore oil platforms in Malaysia, Brunei, the Middle East, and other parts of the world. Their lives are quite different from those of people who still live in longhouses in the interior. These people cultivate hill rice, gather wild vegetables, and fish and hunt for meat. They also raise chickens and pigs for their own consumption. They are self-sufficient and self-reliant. However, some do sell their produce at the market. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026